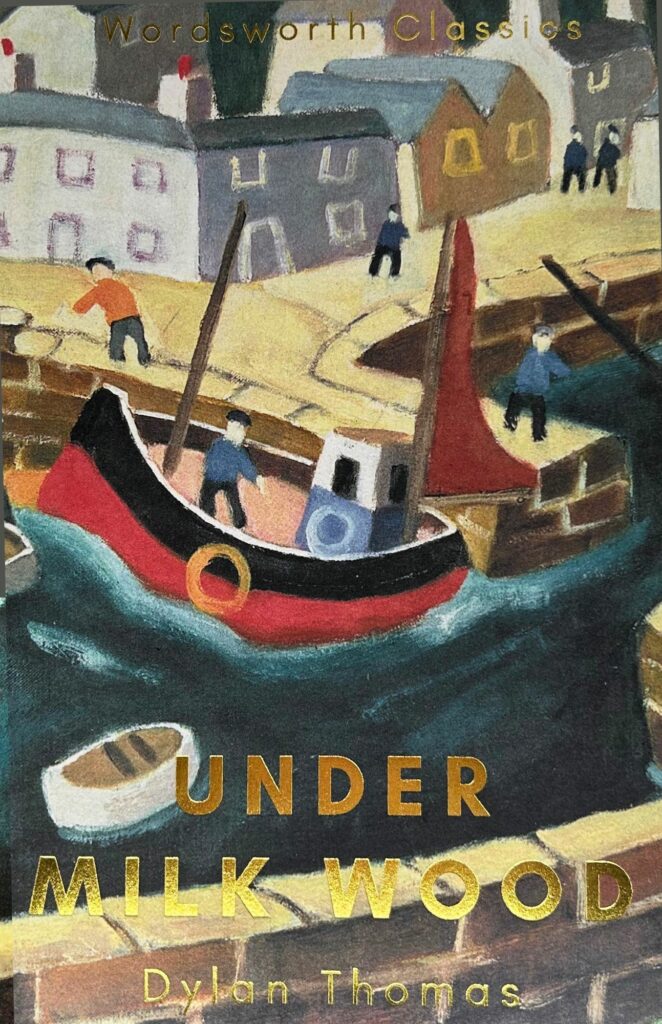

Dylan Thomas, Taylor Swift, and ‘Tortured Poets’

On International Dylan Thomas Day, and as Taylor Swift name-checks Dylan Thomas on her new album, The Tortured Poets Department, Sally Minogue looks at Thomas’s cultural power and the long-standing relationship between poetry and song.

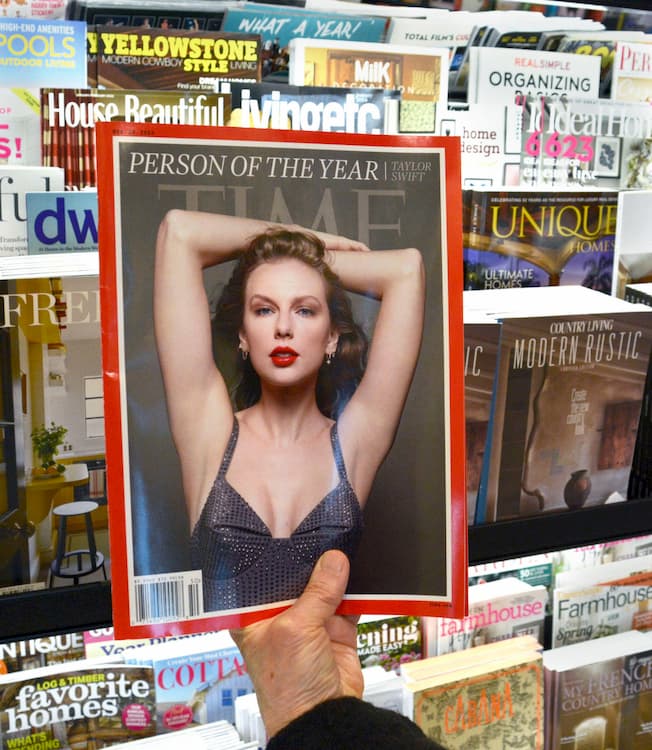

Taylor Swift, Person of the Year 2024

‘Swifties’ (my own fifteen-year-old great-niece numbered amongst them) adore Taylor Swift. It’s no ordinary liking for your average pop star; it’s something consuming, a recognition and at the same time a desire – the music, the voice, the lyrics are all bound up in and with the person herself. I remember that sort of feeling, when someone in the popular eye seems so much what you yourself want to be, or expresses something you hadn’t known you felt. In my day that person was usually a man. In my case, when I was sixteen, it was Adam Faith, and I remember my intense internal feelings of – what? a sort of gratitude and, yes, adoration, when he appeared on Face to Face with John Freeman on television, the ‘Psychiatrist’s Chair’ of the sixties. And he said serious things about life and belief! He was more than just a pop star! I can only imagine what Swifties feel, but maybe it is some of that. Her lyrics and music and the feelings they express are more than ordinary. And now, hurray, it’s a woman.

When I started thinking about this, I wondered how these 21st followers, many of them very young, could grasp the frame of reference in the eponymous song ‘The Tortured Poets Department’: ‘You’re not Dylan Thomas / I’m not Patti Smith /This ain’t the Chelsea Hotel / We’re modern idiots’. The great Patti Smith herself, poet, writer and singer, graciously acknowledged the reference on Instagram with this post:

This is

saying I was

moved to be

mentioned in

the company

of the great

Welsh poet

Dylan Thomas.

Thank you Taylor.

See: This is Patti Smith (@thisispattismith)

Smith accompanied this with pictures of herself reading Thomas’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog (actually Thomas’s short stories rather than his poetry). Note that what Smith was most happy with was that she was connected with ‘the great/ Welsh poet/ Dylan Thomas’. But she also sweetly thanks Taylor Swift. No side to Patti Smith. But do the Swifties know who Patti Smith is? Or the complicated cultural history of the Chelsea Hotel? Let alone that of Dylan Thomas. But then I thought again about my own teenage fandom. We don’t always need to understand a lyric to feel its power. Here we hear ‘Dylan Thomas’, we hear ‘Patti Smith’, they are named as iconic figures; we think of the title ‘The Tortured Poets Department’, and we put Taylor Swift up there and alongside them. If the Swifties get a sense of a world that these references create (that of ‘Tortured Poets’), that’s surely ok. Maybe they are already reading their heroine’s own heroes and heroines, and if not maybe at some point they’ll follow on her heels, and find out about Patti Smith and Dylan Thomas, both formidable poets in their own ways. And both at different times residents of the Chelsea Hotel in New York, famous for the many artists, musicians and writers who at some time stayed there.

The nice thing about Swift’s lyric is that it is self-disparaging. She’s not claiming equity with these poets, quite the opposite: ‘We’re modern idiots’. But there is a depth of cultural, musical and emotional reference there that we should surely be glad of. She’s showing her knowledge, but at the same time recognizing the distance between herself and these big names. The wonders of digital media mean that one of the poets she references, Patti Smith, can actually pop up in her timeline, and that of her countless followers. Patti Smith is still alive, and still very much alive to the culture. But what of the other poet she references, Dylan Thomas? Dead over 70 years now. But Patti Smith is still reading him[1]; and if the lyric is to have any depth, one hopes that Taylor Swift too knows more than his name.

Patti Smith c. 1975

For Swift, Thomas belongs in the ‘Tortured Poets Department’ in which she also places herself. As I’ve been at pains to point out in previous blogs, the notion of Thomas as a tortured poet is not a particularly helpful one, unless one recognizes that the torture is in those punishing rhyme schemes he sometimes subjected himself to. Certainly, in his poetry he is struggling with large emotions and ideas. In his collection Deaths and Entrances, much of it dealing with the subject matter of the Home Front in the Second World War, he confronts deaths in the Blitz, ranging from that of a child to a very old man. But even in those poems he somehow wrenches a triumph out of death. At the other end of the spectrum are his rhapsodically lyrical poems, often those celebrating his October birthday or his childhood holidays. ‘Poem in October’, which in Collected Poems 1934-1952 comes on the page after ‘A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London’, is a pure celebration of the joy of life:

A springful of larks in a rolling

Cloud and the roadside bushes brimming with whistling

Blackbirds and the sun of October

Summery

‘Fern Hill’, a paean to his childhood innocence and that of every child, Wordsworthian in its absorption in and celebration of nature, was actually written at the very end of the Second World War. Somehow, out of the horrors of the previous six years, he was able to conjure pure joy:

Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green,

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes,

And honoured among wagons I was prince of the apple towns

Now in that same collection Deaths and Entrances, from which all the poems quoted above come, there are certainly individual poems which can qualify for the ‘Tortured Poets Department’. Those are the poems about Thomas’s relationship with his wife Caitlin, well-documented as both passionate and destructive, in large part because of their joint dedication to drink. ‘On a Wedding Anniversary’ is not the poem one would want to receive on one’s wedding anniversary:

Now their love lies a loss

And Love and his patients roar on a chain;

From every true or crater

Carrying cloud, Death strikes their house.

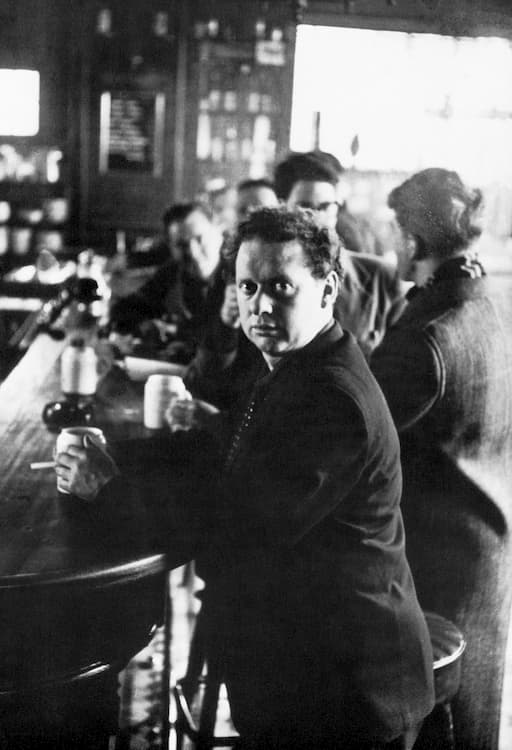

No doubt too Swift is thinking of Dylan Thomas’s own eventual death. Having fallen into a coma in his room in the Chelsea Hotel in November 1953, he died in hospital in New York a few days later.

Dylan Thomas, New York City 1952

Dylan Thomas has, more than most poets, caught the imagination of modern singer-songwriters. The most famous of these is obviously Bob Dylan. Whilst the connection between his assumed name and that of the poet has never been firmly established, everyone knows really that Dylan called himself after Dylan. I might not have quite the Swiftie dedication, but a delight in Dylan is the closest I come to it. He has mirrored my own life in an extraordinarily long musical career. His earliest folk/acoustic albums were coming out in my adolescence when his politics were mine. I remember his electric moment of betrayal, though in fact he was just keeping up with the times, and his music got stronger and richer. I fell out with him at his religious stage. And I have come back to him in my later years. In my sixties I went to see him at the Wembley Arena and he actually sang my favourite ‘The Ballad of Hattie Carroll’, which he NEVER sings. Of course I felt he was singing it for me. Like any true poet he has developed and developed and developed, and yet stayed himself. When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature I said to myself, quietly, ‘Yes’.

The relationship between popular music and poetry has always been vexed. The lyric of a popular song is one thing, and a poem is another. But sometimes claims are made for song lyrics to be seen as on a par with poetry. The esteemed literary critic Christopher Ricks, acclaimed Professor of Literature in England and America, and writer about and editor of many significant poets, has written a whole book about Dylan’s lyrics. I was once lucky to be in conversation with him, and he described the moment when Dylan summoned him to meet. According to Ricks, Dylan greeted him: ‘So, Mr Ricks, we meet at last’. Ricks was, happily and unashamedly, a pure fan. This was the moment of his life. Taylor Swift has her own academic groupie. Jonathan Bate, Shakespeare expert and great exponent of the Romantic poets, has recently claimed that she is ‘a real poet’ and can be considered as an interesting re-interpreter of Shakespeare. (see www.independent.co.uk )Well, we are all subject to our own swooning moments when we come close to those we adore. And I say this not critically, but in admiration that Bate admits to being human like the rest of us – in this respect just another ardent fan. Who we choose to be fans of seems to be somewhat outside our control. Tortured Poets Department

While there might seem something slightly embarrassing about making literary claims for what is essentially pop music, that above-mentioned Nobel Prize awarded to Bob Dylan forever put the imprimatur on the song lyric as poetry. After all, in the sixteenth century, the two were intimately intertwined, and folk ballads have always had a special status in literature. Certain poets, such as Robbie Burns, slid easily between both worlds, using Scottish dialect and ordinary language in lyrics that could be both sung and spoken. Think of ‘My love is like a red, red rose’. Thomas himself used extraordinarily simple vocabulary in many of his poems, even though each word may be freighted with symbolic meaning. Many of his best poems are written predominantly in monosyllables. ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’ is a superb example – a poem that has lent itself to many a funeral, replacing as it does the impotence people often feel in the face of loss with a restrained fury: ‘Rage, rage against the dying of the light’. This has led to his work being set to music. Cerys Matthews, a great proselytizer for Thomas’s work, set both his poetry and prose in her album ‘A Child’s Christmas, Poems and Tiger Eggs’ (2014) and Cerys too recently noted Taylor Swift’s nod to Thomas, this time on Twitter. But his musical inspiration goes right back to the years after his death. Igor Stravinsky, who had been corresponding with Thomas about writing an opera together when Thomas died, wrote a song sequence ‘In Memoriam Dylan Thomas’ based on ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’, while jazz pianist Stan Tracey wrote a Jazz Suite in 1965 inspired by Under Milk Wood. What is notable in the way his work inspired composers, musicians and singers is the evident crossover between, classical, jazz and popular song. Taylor Swift follows on from a prestigious tradition.

Chelsea Hotel, New York City

Dylan Thomas would, I am sure, have been thrilled to be still going strong in popular culture. He wasn’t one for the ivory tower, his pleasure in the world of the pub with its gossip and liveliness of language was as strong a pull for him as the beer itself. Go to his stories – those same ones Patti Smith is holding in her hands on Instagram, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog – to find brilliant evocations of a small town world with characters holding on precariously to their small joys in the midst of quiet desperation. Much of his own poetry, including some of his best-loved poems, was written into notebooks when he was still in his teens, and he was first published in a London magazine when he was only eighteen. ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower’, published just before his nineteenth birthday, celebrates the life force at its strongest; it, again, is driven largely by monosyllables. His is a poetry that can certainly speak to the young, and not just about angst, but also about happiness. I expect Taylor Swift does that too, and she has the advantage that her followers can dance to the music of her time and of their own. From the little I have gleaned from the massive social media buzz that surrounds Taylor Swift, much of it self-generated, this new album is about the breakdown of a love affair. But I gather it is also about recovery, being a strong woman, forging ahead, and so on. So the lyrical and natural pleasures Thomas offers in his poetry might also be called on. Have a look at ‘Fern Hill’, TS, and crest the wave. All power to you and your followers.

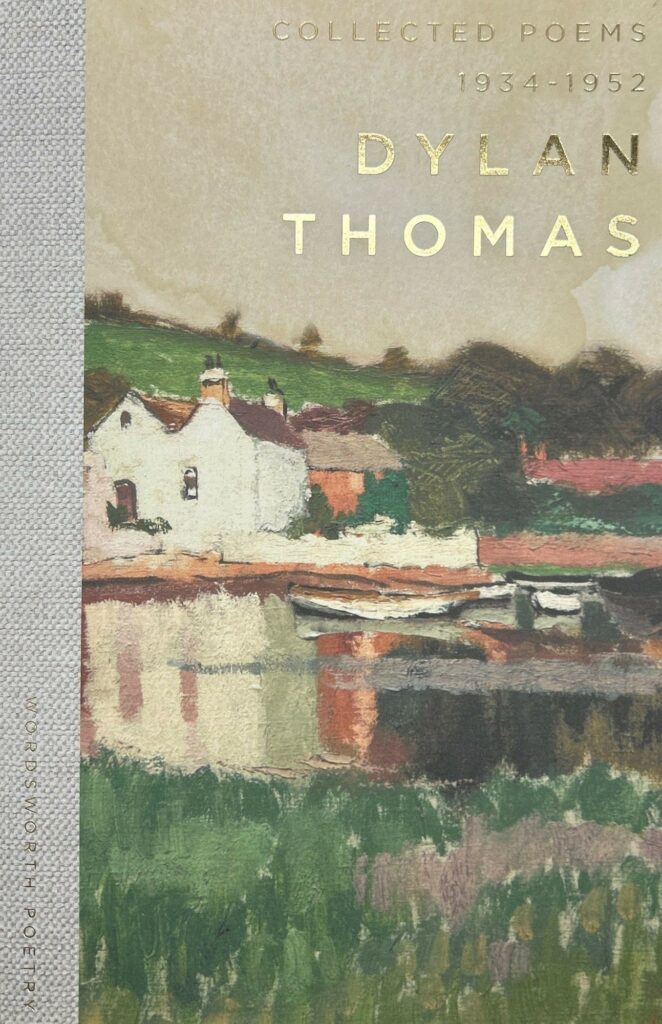

Wordsworth Editions publish Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems: 1934-1952 and in a separate volume, Under Milk Wood and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, both with a full Introduction and Notes by Sally Minogue. They can be found here: Thomas Dylan – Wordsworth Editions

[1] Smith has always been a great aficionado of literature, from her association in the 1960s onwards with Allen Ginsberg and the Beat poets, to her 2013 visit to Haworth to pay homage to the Brontës and, while she was there, do a benefit gig.

Main image: Copies of the Taylor Swift album, ‘The Tortured Poets Department’, on clear vinyl, on display in a record store window. Credit: Hazel Plater / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Time magazine with a cover photograph of Taylor Swift, the magazine’s 2024 Person of the Year. Credit: Shiiko Alexander / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Patti Smith. Promotional photo of US singer about 1975 Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Dylan Thomas in the White Horse Tavern, Greenwich Village, New York City, 1952. Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: The Chelsea Hotel, New York City Credit: Victor Korchenko / Alamy Stock Photo

Tortured Poets Department

Tortured Poets Department

Books associated with this article

Collected Poems 1934-1952

Dylan Thomas