Stefania Ciocia looks at Pinocchio

Crossing boundaries with Pinocchio: Stefania Ciocia meanders through matters of language, culture, genre and authorship with the world’s most famous puppet.

There is something profoundly human about the collaborative imaginative effort shared by actors and the audience in the theatre. There are few occasions when I feel so connected with other people as in the collective suspension of disbelief and – even greater bliss – the synchronized enjoyment with which we respond to engaging live performances. The more overt the artifice, the more moving the experience for me: the potential effort involved is bigger, but so too is the marvel that giving oneself to the illusion feels like no effort at all. (That’s one of the reasons why I love opera, I guess.) Besides, while I am as charmed as the next person by the genuine wonderment that children can bring to bear on the proceedings, what tickles me – or, in my more melodramatic moments, kind of breaks my heart – is the willingness to get carried away that is required of us adults, and the cheerful sense of excitement that some of us draw on, especially when the material being breathed life into is conceived, in part or entirely, for a much younger audience. Live performances rekindle my playful side, as readers of my blog posts on Peter Pan and, more recently, Julius Caesar already know.

The English word “play”, with its dual connotation of theatrical and ludic, captures the spirit of exchange between stage and auditorium, and the active participation demanded of an audience, much more effectively than its Italian equivalents, the cumbersome “opera teatrale” or the loaded “commedia”, “dramma” and “tragedia”. I am thinking of matters to do with translation because the National Theatre production of Pinocchio, the show that originally prompted this piece,[1] expertly navigates through several boundaries: it negotiates linguistic and cultural differences between the original Italian text and its British production, it revisits a story written for children but targets, as is usual these days, a crossover audience, and it brings to the stage a classic book by way of its more famous cinematic adaptation.

Poor Carlo Collodi, the author of the original Le Avventure di Pinocchio (1883), is not mentioned in the NT advertising material at all. This is Pinocchio by Dennis Kelly, and it is promoted on the strength of its creative cast (I can almost hear the movie-trailer voice-over: “from the ‘director of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child and the writer of Matilda the Musical’”), and of its beloved soundtrack (“[f]eaturing unforgettable music and songs from the Walt Disney film including I’ve Got No Strings, Give a Little Whistle and When You Wish Upon a Star”). This is where a bit of cultural dissonance kicks in for me: is this really the rightful frame of reference for the adventures of our lively wooden puppet? Has his story been so completely hijacked by Disney that Collodi won’t even get a look in?

Of course, I am familiar with the 1940 film, Disney’s second feature-length animation after the huge success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). I’m pretty sure I saw it as a child, I certainly had a copy of the Disney picture book and, before the performance, I could have hummed the Wish Upon a Star tune, though I’d have had to make up the words even in Italian. I have since watched the cartoon in English for the first time, as “research” for this piece (unlike Pinocchio, I do my homework), and can confirm that I prefer the two other, lesser known, songs. Musically, as well as with their lyrics, they intimate greater agency than merely trusting in fate: I’m rather partial to the soupçon of hedonism in No Strings, while the similarly upbeat Whistle – a great little tune – is a rallying cry for the moral cavalry to come and help us resist temptation. Incidentally, here is where Whistle and I part ways: it captivates me musically, but I am with Wilde, not Jiminy Cricket, on the subject of temptation.

Something else I can’t quite reconcile myself with, even if I should know better, having taught the book to a couple of cohorts of British students a decade or so ago, is the idea that many people think of Pinocchio as a story whose folkloric origins are lost in the mist of time, like ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, ‘Puss in Boots’ or ‘Bluebeard’, rather than as the brainchild of an individual author.[2] In fact, Collodi launches his story with the conventional fairy tale formula only to disappoint it:

“Once upon a time there was…”

“A king!”, my young readers will immediately pipe up.

“Wrong, boys and girls. Once upon a time there was a piece of wood.” [my translation]

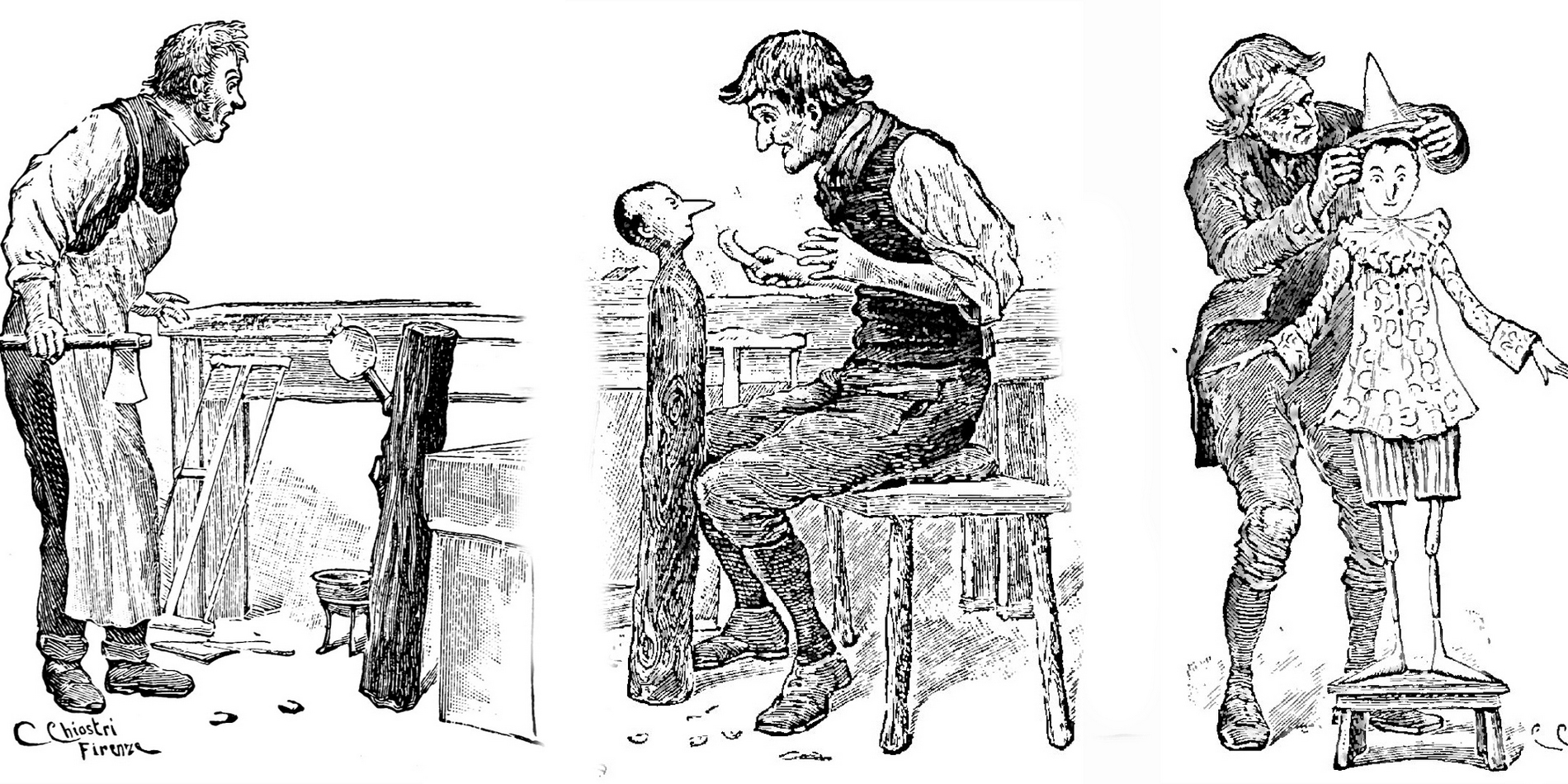

It’s true that Pinocchio’s adventures are full of mythical and archetypal motifs (see the hero’s search and rescue mission, or the journey into the belly of the whale), of references to folklore (the puppet himself is closely related to the Commedia dell’Arte trickster characters, as we see in Mangiafoco’s theatre, where Arlecchino and Pulcinella greet him as a long-lost family member) and to fables (the Cat and the Fox, and the many other talking animals, could have stepped out of Aesop’s stories or La Fontaine’s).[3] The narrative is peppered with fantastic metamorphoses, often without rhyme or reason: the worst culprit here is the Fata dai capelli turchini (the Blue-Haired Fairy). We first encounter her as a girl with waxen complexion, as well as distinctively colourful locks. While no explanation is given about her mane, her pallor makes perfect sense once we find out that she is dead because she says so (!) to Pinocchio. The puppet is not exactly on top form himself: he’s been hanged off the Great Oak by the assassini, and is about to exhale his last breath.

Believe it or not, this macabre exchange, followed by Pinocchio’s demise, is where the Storia di un burattino (Story of a Puppet) ends in the initial serialization for Il giornale per i bambini (The Children’s Newspaper) in 1881. Resurrected at the insistence of readers, our hero is nursed back to health by the Fairy, who wavers between tenderness and, frankly, sadism in getting him to behave throughout the narrative. At one point she feigns her own death to teach him a lesson; later on, she leaves him waiting outside her house all night in the rain; in bed asleep, she is not to be disturbed: no matter that the servant who ‘hurries’ to let Pinocchio in is a Snail. At critical junctures in the plot, however, she miraculously reappears in various womanly guises and once, for good measure, as a blue-haired little goat. A goat. On a rock. In the middle of the sea. The mind boggles. Still, her presence alone perhaps is reason enough why this novel, when abridged and Disneyfied, is so easily mistaken for a – the clue is in the name – fairy tale.[4]

Against the Fairy’s random protean changes, other transformations make absolute sense: turning into an ass is an eminently predictable fate for stubborn, naughty children who skive off school, refuse to learn their lessons and disobey their elders. In Italian, the synonyms for “ass” (somaro, asino, ciuccio) all have this particular connotation, though I suspect that the asinine – see: it’s here in the English word too! – brain’s reputation is in reality much maligned. Literarily, rather than linguistically, Pinocchio’s scary mutation further gestures to Apuleius’s Metamorphoses, or The Golden Ass (2nd century A.D.), whose protagonist Lucius spends the best part of the narrative in braying animal form.

In spite of its attendant trials and tribulations, this unwitting disguise – the man has turned himself into a donkey by mistake, while practising magic – allows Lucius to witness unnoticed (or listen to, with his long ears) various criminal, sexual, and generally scandalous capers. A tale of helplessness and survival to being stolen, abused and nearly killed several times, The Golden Ass is widely regarded as the Latin forerunner of the picaresque novel: Lucius is always on the move from one misadventure to the other, and his travels and travails only interrupted by embedded stories which add to the episodic feel of the entire text. Collodi shares with Apuleius and the picaresque tradition certain darkness, crudity and the breakneck sequence of the hero’s haphazard escapades. His Pinocchio is a glorious mess of a book, with noticeable stops and starts (the abrupt original ending comes to mind again). It is a much more anarchic, sprawling affair than Disney’s adaptation, or the National Theatre’s, where the story is tamed in more ways than one. And on this note, we must indeed stop: in the spirit of containing centrifugal narratives, the exploration of this whole matter is better left to the next instalment of our blog.

[1] I saw the production at the beginning of April, the day before my Julius Caesar jaunt. I had set out to review both plays, but other things – mostly my day job – got in the way of this best-laid plan. It happens. As a result of my mulling things over for several weeks, this blog has morphed from a relatively straightforward, hot-off-the-press review into something different, less spontaneous, and more circuitous: a bit like Pinocchio, who starts off on an odd little journey but takes several different turns along the way, not least in his literary afterlife.

[2] I wonder why the same is not true of Alice in Wonderland. Is this to do with how a text travels across linguistic and national boundaries? Do I know about Collodi because I am Italian, or because I am a bookworm? Do Italian children these days know about Collodi, or do they think Disney created Pinocchio and Tim Burton Alice?

[3] There are also more learned literary allusions: for example, the guard-dog Medoro is named after Angelica’s love interest in Orlando Furioso, Ludovico Ariosto’s marvellous epic poem, first published in 1516. While mixing and matching a variety of fantastic literary traditions with gleeful abandon, Collodi also sets his characters against a very realistic, and place-specific, background: witness the references to regional cuisine (“risotto alla milanese” and “maccheroni alla napoletana”), or to the “carabinieri”, the Italian gendarmerie. The bite of hunger and injustice – the lot of the unprivileged classes – is made sharper by this concrete, vivid details.

[4] In this case, the Italian word has the upper hand: “fiaba” (from the Latin fabula, i.e. “story”) is aptly devoid of the unnecessary connection with the realm of fairies so foregrounded in its English counterpart. There are plenty of fairy tales that do not include such creatures, and the reverse is indeed also true: one fairy does not a fairy tale make.

Books associated with this article