A Crescent Still Abides

Stefania Ciocia reflects on grief, and Emily Dickinson, on All Souls’ Day

As the carnivalesque spirit of Halloween subsides, people from Christian communities all over the world mark All Souls’ Day, or the Day of the Dead, on 2 November. The date is an unofficial national holiday in many Catholic countries, including my native Italy, where families often get together to visit the final resting place of their loved ones. I have taken part in these pilgrimages myself, the whole extended family converging from the opposite ends of the peninsula to the little village in the Veneto region where my maternal grandparents, and two of my great-grandparents, are buried. I have always found these gatherings uplifting: deeply-felt absences are momentarily filled by the sharing of happy memories, and the collective sadness gets parcelled out, further defused by the necessity to attend to babies and toddlers, the new generations in the family. It has been a while since I have been able to join these reunions. If I were able to travel back to Italy this November, the whole ritual would have a novel rawness for me.

Like most of us, I have occasionally faced times of great sorrow, but I had never really understood grief until very recently. My mother died ten weeks ago, and yes, I am still counting, though in my daily life I have ostensibly resumed my routine and achieved a “new normal”, an expression a friend of mine used in reference to her own experience of mourning. The thing is I have joined the ranks of the bereaved. Our grief hides in plain sight, ready to creep up on us of its own volition. Sifting through my mother’s make-up was unexpectedly easy. Papà and I even cracked some jokes, teasing Mamma, the way we would have done to her face, for having kept a couple of tiny eye-pencil stubs. She would have given us the silent treatment over that for the whole afternoon, retreating to the kitchen to cook us dinner and make a start on tomorrow’s lunch. The stubs are still in her drawer. About a month later, three weekends ago, I had a quiet, steady crying session to the soundtrack of Puccini’s Suor Angelica. Mamma didn’t care much for opera, and I’d listened to powerful, emotional music since her death with no discernible effect on my tear ducts. Go figure.

A similar unpredictability extends to my willingness to talk about her, and the comfort I derive from sharing my memories of her. I have told the story of this past summer to many people, modulating it differently depending on my closeness with the listener (or reader) in question, or more simply on my mood and my emotional energy at the time. Still, especially if I happen to come across old friends whom I see only sporadically, I am quick to accost them with my piece of news, Ancient Mariner-style, so as to forestall the inevitable, awkward u-turn that would follow my failure to oblige them with small talk.

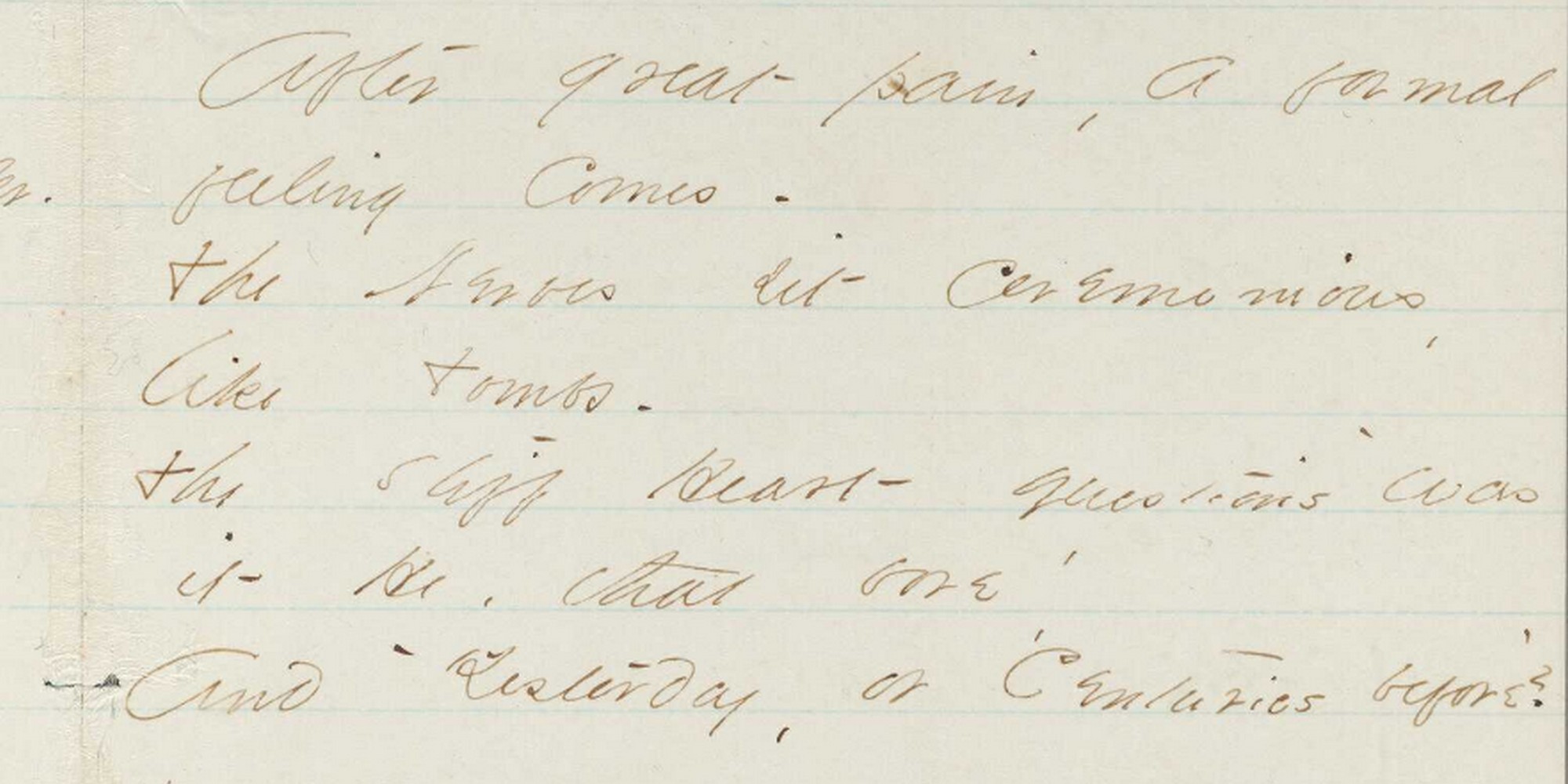

Reading about grief has also given me solace. I haven’t gone out of my way to source the right material, and I am not binging on it. Rather, it seems to have found me, often through small offerings from kind friends. The one poem I have sought out is Emily Dickinson’s ‘After great pain, a formal feeling comes –’. It speaks to me of that underlay of numbness that grabbed me as soon as I got the phone call about Mamma’s imminent death, and that persisted in the following days, when I busied myself in the practicalities of the funeral arrangements, and in trying to step into her shoes, as her elder child and only daughter. “The Feet, mechanical, go round – / A Wooden way” (ll. 5-6), while the “stiff Heart” flounders, confused, its perception of time elastic, slackened, undone. “This is the Hour of Lead” (l.10), heavy and yet barely registering on our consciousness. “Remembered, if outlived, / As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow – / First – Chill – then Stupor – then the letting go –” (ll.11-13).

Dickinson is brilliant at capturing extreme psychological states; as Adrienne Rich remarks, her poetry “says, at least: ‘Someone has been here before”, though the paradox of bereavement – as another wise friend of mine pointed out to me the other day – is that it is utterly banal in its universality and nonetheless shockingly life-changing for each individual it affects. Elsewhere life goes on. Here too I am reminded of another poem by Dickinson, ‘Apparently with no surprise’. The demise of a “happy flower” (l.2) is conveyed with no concessions to sentimentality, in the brutal acknowledgement that this sudden death – a beheading no less – is not exactly premeditated: after all, the murderous frost has merely wielded its “accidental power” (l.4). Nature’s indifference, however, is landed squarely at the feet of “an approving God” (l.8) in the final line of the poem. It’s for Him that “[t]he sun proceeds unmoved / To measure off another day” (ll.6-7), an accusation whose blasphemous charge seeps through its matter-of-fact tone.

And yet the uncompromising Dickinson knows too how to be the purveyor of more traditional consolation. I must thank a third, generous friend for sending me this poem, which I have forwarded in turn to my fellow mourners. Here it is, in full:

Each that we lose takes part of us;

A crescent still abides,

Which like the moon, some turbid night,

Is summoned by the tides.

Mamma is that crescent in me now. And this is another paradox of death: she has never been more intensely with me than in her absence, though even before she went she was with me in ways that I wasn’t fully aware of. Take these blog posts. Mamma would read them, of course; in fact, she’d sometimes ask that we read them together so that I could gloss the words and turn of phrase she couldn’t quite understand. One of the posts we pored over together was that on Little Women. She was inordinately happy about it because it gives pride of place to her father, Nonno Alberto. She nevertheless observed that it mentions my own dad and my brother too and that only she is missing from the roll-call of my immediate family. She pretended to have taken offence at this omission, and jokingly insisted that I should write about her one day. Today is not the occasion on which I was hoping to do so, and this thought has very nearly stopped me from jotting down this piece.

As I have been thinking about how to give Mamma her due and celebrate her life, I’ve realized that I have already written about her, albeit not explicitly. Last December, on the morning of my flight back to England after my Christmas visit, Mamma and I sat on the sofa and went through my review of Sally Cookson’s production of Peter Pan. I wrote that the “real magic” of the story happens not so much in the flights of fancy to Neverland, nor in Peter’s eternal playfulness. Instead, it’s there in the lesson of the play’s closing scene, “when the more experienced amongst us help our charges to fly away, unencumbered by insecurities and emboldened by the knowledge that ‘the window will always be open”. I trust that Mamma recognised herself in these words, as we translated them together a little over ten months ago.

In memory of Marilena De Lorenzo

Stefania has asked us to donate her fee for this article to Cancer Research UK www.cancerresearchuk.org

Picture Credits:

Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

http://hcl.harvard.edu/libraries/houghton/collections/modern/dickinson.cfm

Dickinson, Emily, 1830-1886. Poems: Packet VI, Fascicle 18. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862.

Houghton Library – (26c) After great pain, a formal feeling comes -, J341, Fr372

Publication History

Atlantic Monthly, 143 (February 1929), 184, and FP (1929), 175, with the transposition, as three stanzas of 4, 5, and 6 lines; in later collections, as three quatrains. Poems (1955), 272-73, with line 7 before line 6; also CP (1960), 162. MB (1981), 395, in facsimile. (J341). Franklin Variorum 1998 (F372A).

-History from Franklin Variorum 1998

Emily Dickinson Archive

http://www.edickinson.org

Copyright & Terms of Use:

CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

http://www.edickinson.org/terms

Books associated with this article