Walt Whitman turns 200

As we celebrate the 200th anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth, Sally Minogue looks at his enduring appeal to British audiences.

Whitman’s in the news again, and not just because it’s the 200th anniversary of his birth on this day. Naomi Wolf in her new book Outrages: Sex, Censorship and the Criminalisation of Love (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), which has attracted both notice and controversy, places Whitman as the literary hero of her narrative. Wolf argues that there’s a close connection between literary censorship and anti-homosexual legislation and homophobia. She uses the impact of Leaves of Grass on its nineteenth-century British audience as a sort of test case for this. But this is just another iteration of the way in which Whitman and his work have constantly renewed themselves, and in particular, have found an enduring place in the British consciousness.

Whitman’s first edition of Leaves of Grass, published in America in 1855, received several reviews in leading English journals in 1856. The reviews (whose anonymous authors remain unidentifiable) in The Saturday Review, The Literary Examiner and The Critic are the written equivalent of a shudder. What exactly they are shuddering at is itself too much even to be named; one describes Whitman’s intentions in the poem as ‘exceedingly intelligible, but exceedingly obscene’ while another compares Whitman in one breath to Caliban, in the next to a ‘hog’, finally characterising him, as if in the same animalistic terms, as ‘the poet of the body’. Their summary judgements are that ‘the depth of his indecencies will be the grave of his fame’, and ‘if the Leaves of Grass should come into anybody’s possession, our advice is to throw them instantly behind the fire’. Bodies, beasts, book-burning: this is the language of fear. We have to go to none other than George Eliot for an acute, intelligent and moderately sympathetic review. Her first, in the Westminster Review, April 1856, simply quotes at some length (a common practice in nineteenth-century reviews), but her second in The Leader in June of the same year, clearly ‘gets’ Whitman. For her, the central impulse of the poet is that he ‘beholds all beings tending towards the sovereign Me’. Even the cool-headed Eliot is seduced by his candid embrace, eliding him throughout to ‘Walt’ – ‘one of the most amazing, one of the most startling, one of the most perplexing creations of the modern American mind’. She does have some reservations, conceding that it is good not to be ashamed of Nature … but it is good, sometimes, to leave the veil across the Temple’. But she is in no way alarmed.

The (probably male) anonymous reviewers’ references to ‘obscenity’ and ‘indecencies’ are doubtless responses to ‘Song of Myself’ which opened the 1855 edition (though not yet with that title). The more explicitly homoerotic Calamus poems were not yet written. But there was still plenty of the flesh to disturb – perhaps especially the male – reader:

I mind how we lay in June, such a transparent summer morning:

You settled your head athwart my hips and gently turned over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my barestript heart,

And reached till you felt my beard, and reached till you felt my feet.

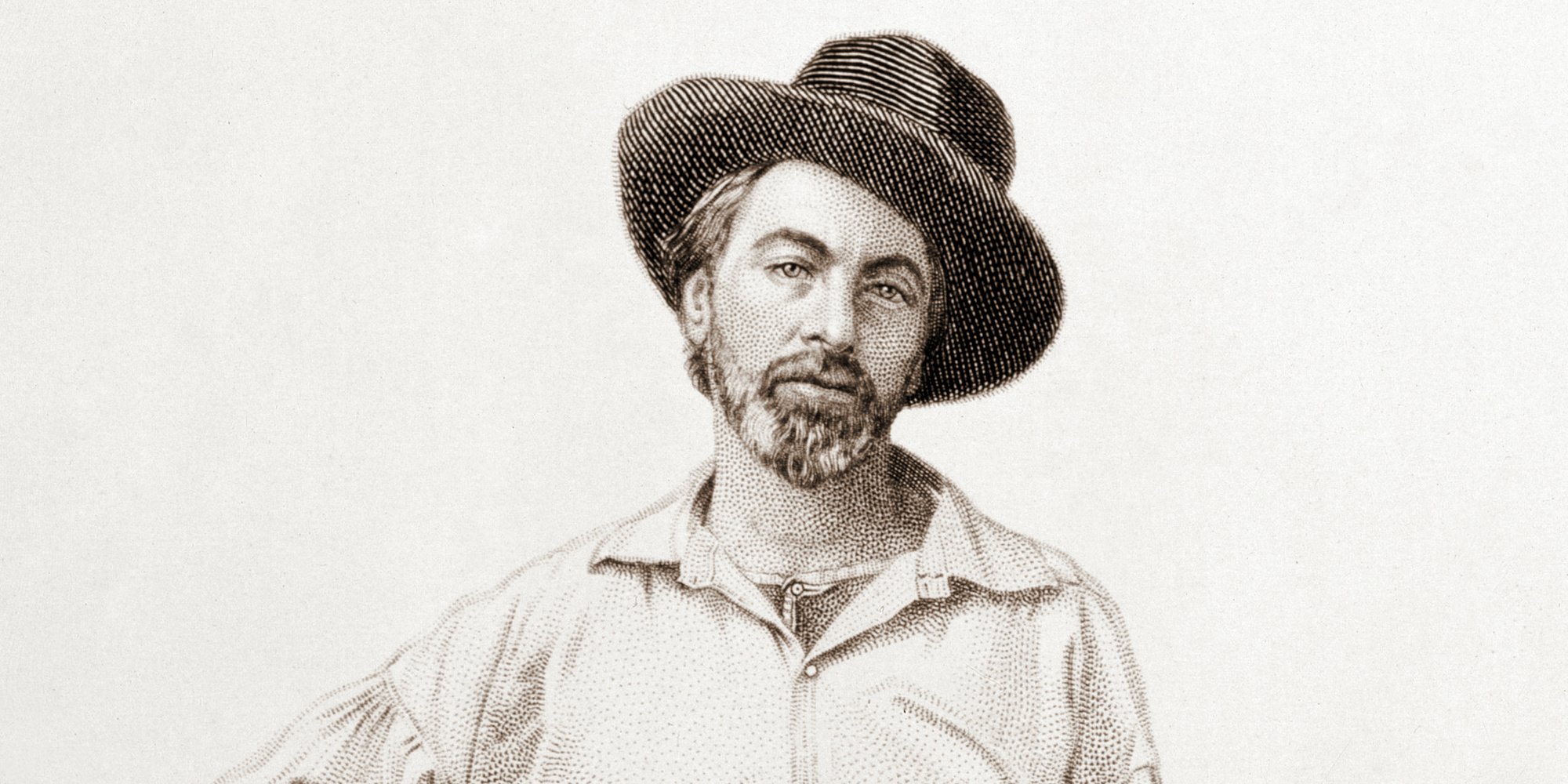

Hmmm. It would be interesting to know what George Eliot made of this; doubtless, this is where she thought a veil might be better drawn. Yet these are perhaps the same passions she depicts in her love-driven Maggie in Mill on the Floss – only the language is different. But of course, that difference in language makes all the difference. Where Eliot had to use the metaphor of the flood, Whitman dispenses with anything that stands for, in favour of the thing itself. And in case his readers needed a reminder of the actual body behind the poem, the 1855 edition was famously accompanied by the photographic portrait which announced its authorship. Only too easy to look at that frank, loose-limbed portrait and see the ‘bosom-bone’ and the ‘barestript heart’.

That was probably Whitman’s intention. Although he dispensed with his own name on that first edition (reviewers had to find it instead in the text itself), putting his photograph as the frontispiece was a much more intimate act. The Whitman Archive (https://whitmanarchive.org) catalogues all 130 photographic images of the poet, and in a superb introduction to that fascinating gallery, Ed Folsom shows how the span of Whitman’s life ran alongside the development of photography. The first daguerreotypes appeared when Whitman was twenty; by the end of his life, roll film and small cameras were democratising the medium – a development he would have delighted in. Folsom shows how extraordinarily reflective Whitman was about the nature of the photographic portrait and its implications for human reflections on the self. Joking that the camera itself must be tired of him, so many were the photographs of him, he says ‘I meet new Walt Whitmans every day. There are a dozen of me afloat. I don’t know which Walt Whitman I am.’ But in using that self-image at the head of the 1855 edition of the first leaves of his great prairie, he knew very well which Walt Whitman he wanted to present to his readers.

Perhaps those review mentions of obscenity and indecency had taken the temperature of the times; in England, the new Obscene Publications Act of 1867 caught Leaves of Grass in its net (though Wolf suggests that the poem continued to circulate clandestinely). The subsequent English edition, 1868, edited by William Michael Rossetti, a relative of Dante Gabriel and Christina, transformed Leaves of Grass into Poems by Walt Whitman. It was severely bowdlerised to escape the proscriptions of the Act, and only reluctantly endorsed by Whitman. A further English edition in 1886, Leaves of Grass: The Poems of Walt Whitman, Selected, with Introduction by Ernest Rhys, was similarly mangled, but Rhys at least had the good and express intention of producing a cheap version accessible to the working man. Both these editions omitted the all-important ‘Song of Myself’. (https://whitmanarchive.org/published/books/other/british/intro.html)

It was one or the other version that reached (and fitted into) the pockets of soldiers in the First World War, though also highly influential here was the separate republication in England by Chatto and Windus of the ‘Drum-Taps’ section of Leaves of Grass in 1915, with an Introduction reprinted from the Times Literary Supplement (April 1915), linking what had originally been Whitman’s response to the American Civil War directly to the new conflict.

It was to the Chatto publication that First World War poets such as Ivor Gurney and Isaac Rosenberg responded, making a comparison with Rupert Brooke’s 1914 sonnets which was not favourable to Brooke. [see my previous blog here]. Prior to the war, Ralph Vaughan Williams and Frederick Delius had both set some of the poems from Whitman’s ‘Sea-Drift’, Vaughan Williams in A Sea Symphony (1910), and Delius in Sea Drift (1906). Whitman was, then, in the English cultural ether in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Whitman’s next incarnation, both in America and England, came in the 1960s. The American Beat poets led by Allen Ginsberg unsurprisingly reinvented Whitman in their own image, while Thom Gunn moved Stateside and flourished in America as a poet, as he felt he could not and would not in England. A common denominator here is gayness. The late 60s and early 70s saw what had remained covert in literary analyses of Leaves of Grass become overt in the heady days of Women’s Liberation, Gay Liberation, and – briefly – political liberation. Whitman’s homoeroticism was finally and fully acknowledged. In England the 1959 revision of the 1867 Obscene Publications Act he’d fallen foul of now allowed the literary merit of work as a defence against the charge of obscenity. Penguin tested the act with the publication of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960 and won.

Lawrence was highly ambivalent about Whitman; he really didn’t like the way Whitman wanted to embrace EVERYTHING! And, as with those first English reviewers, there is something of fear in his response, perhaps because of the unresolved contradictions in his own feelings about male-male love. But as Lady Chatterley hit the high street with its recognition of female sexuality, and Whitman was released in the fullness of his sexual identity in new readings of Leaves of Grass, something came full circle. Whitman certainly proved that feller wrong about his indecencies being the grave of his fame.

And for the twenty-first century, and Whitman 200 years on? There is literally something for everyone in Leaves of Grass, and intersectionality is aplenty. But what we should most embrace there is the celebration of humanity in its equal diversity which Whitman announced as paramount in its Preface: ‘A great poem is for ages and ages in common and for all degrees and complexions and all departments and sects and for a woman as much as a man and a man as much as a woman’. Read this great poem, and that is what you will find.

Books associated with this article