Mia Rocquemore looks at the works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson

“It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles”

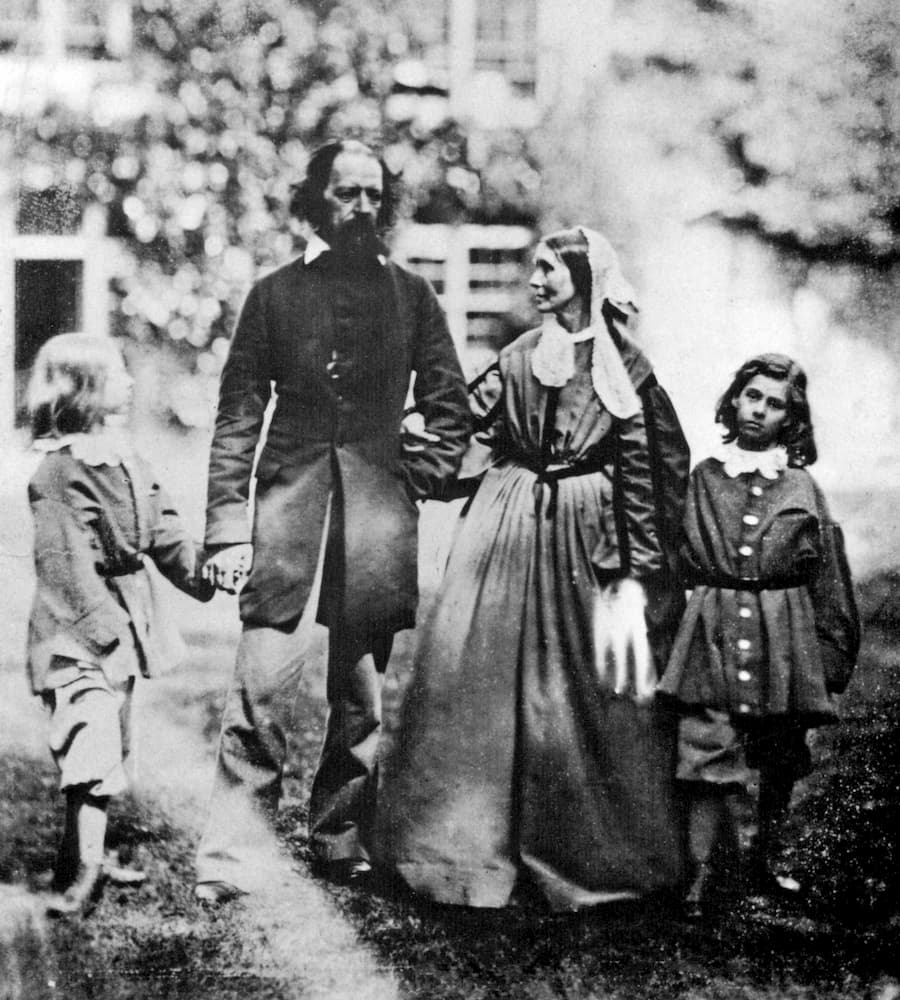

Tennyson and his family

Many of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s most beloved poems are set on the water. In Crossing the Bar, the eighty-year-old poet, writing as he passed over the Solent to the Isle of Wight, hopes that his own death will resemble “such a tide as moving seems asleep”. Hallam Tennyson later wrote of his father’s passion for the water, recording how he would gaze endlessly into the depths of the sea on voyages.

The prominence of the ocean in Tennyson’s poetry needs come as no surprise. Steeped in Classical influences, he drew a great deal of inspiration from the literature of a time and place when seafaring was necessary, dangerous and, consequently, often heroic. Despite its secrets and its risks, the sea offered those with enough skill and courage the opportunity to discover new places, people, riches and knowledge. It also offered Tennyson the perfect symbol with which to explore ideas about curiosity, the unknown, and the extent to which humans are able to exert control over nature. Islands play a central role in this exploration, where the safety and familiarity of the land give way to the excitement and adventure of the open sea.

Liberated from the mainland, the island offers an unimpeded view of a vast and seemingly endless frontier bursting with unknown possibilities. Timbuctoo, one of Tennyson’s earliest published poems, which won him the Chancellor’s Gold Medal for poetry at Cambridge, begins with the speaker standing on the peak of a mountain and looking out over the ocean. He imagines a scattering of islands, each with its own natural pleasures, painted in jewel-like hues and infused with a sense of the supernatural, even the divine:

“Where are ye,

Thrones of the Western wave, fair Islands green?

Where are your moonlight halls, your cedarn glooms,

The blossoming abysses of your hills?

Your flowering Capes, and your gold-sanded bays

Blown round with happy airs of odorous winds?

Where are the infinite ways, which, Seraph-trod,

Wound thro’ your great Elysian solitudes,

Whose lowest deeps were, as with visible love,

Fill’d with Divine effulgence, circumfused,

Flowing between the clear and polish’d stems,

And ever circling round their emerald cones

In coronals and glories, such as gird

The unfading foreheads of the Saints in Heaven?”

Images of untrammelled, exotic locales would certainly have appealed to the Victorian imagination; ongoing British exploration and colonial influence in every continent meant that Tennyson’s contemporaries were well-fed on a diet of exciting reports, stories and drawings from far-away lands. The Victorian fascination with the exotic is reflected in the idealised image of the island found in much of his poetry. The unnamed protagonist of Locksley Hall, for example, longs

“…to burst all links of habit – there to wander far away,

On from island unto island at the gateways of the day.

Larger constellations burning, mellow moons and happy skies,

Breadths of tropic shade and palms in cluster, knots of Paradise.

Never comes the trader, never floats an European flag,

Slides the bird o’er lustrous woodland, swings the trailer from the crag;

Droops the heavy-blossom’d bower, hangs the heavy-fruited tree –

Summer isles of Eden lying in dark-purple spheres of sea.”

In The Islet, however, which Tennyson started in the mid-1850s but did not publish until 1864, this blissful image is cast into doubt. The poem, which has been read as a reaction against or parody of pastoral verse, takes the form of a dialogue between a singer and his new wife. Upon her asking where they are to live together, the singer begins by describing

“’…a sweet little Eden on earth that I know,

A mountain islet pointed and peak’d;

Waves on a diamond shingle dash,

Cataract brooks to the ocean run,

Fairily-delicate palaces shine

Mixt with myrtle and clad with vine,

And overstream’d and silvery-streak’d

With many a rivulet high against the Sun

The facets of the glorious mountain flash

Above the valleys of palm and pine.’”

And yet, when she demands that they leave for this wonderful destination at once, he denies her wish:

‘No, no, no! For in all that exquisite isle, my dear,

There is but one bird with a musical throat,

And his compass is but of a single note,

That it makes one weary to hear.

…

No, love, no.

For the bud ever breaks into bloom on the tree,

And a storm never wakes on the lonely sea,

And a worm is there in the lonely wood,

That pierces the liver and blackens the blood,

And makes it a sorrow to be.’”

Tennyson Down, Isle of Wight

The singer dispels the illusion of the island as a paradise on earth. His complaint against its one and only songbird suggests that perfection, or perceived perfection, soon becomes tedious, while the worm carries connotations of the serpent in the Garden of Eden, which helped bring about the first sin and the fall of man. In this way, Tennyson suggests that their islet is not necessarily the idyllic embodiment of exoticism, freedom and possibility that it first appears.

Indeed, islands often have an uncanny or sinister side to them in Tennyson’s work, their liminality reflecting the fractured or disoriented state of mind and being experienced by his characters. His Ulysses is not the same hero we know from Homer’s poem: now an old man, he is caught between the life he strove so intensely to regain on Ithaca, and the rekindling spark of adventure. The warrior who once fought at Troy, courted demi-goddesses, escaped giants and monsters, and weathered heaven-sent storms cannot abide a life where, “Match’d with an aged wife, I mete and dole / Unequal laws unto a savage race”. Although “Made weak by time and fate, [he remains] strong in will / To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield”.

What is more, his desire “to sail beyond the sunset, and the baths / Of all the western stars” until death, is not simply driven by physical restlessness or borne out of an affinity with the sea per se. It is a longing for experience and knowledge, which he is determined to follow, “like a sinking star, / Beyond the utmost bound of human thought”. Beyond the horizon are not only untrodden lands, but also unfathomed ideas, both of which the aged Ulysses yearns to explore. The barren crags of Ithaca give him a vantage point from which to contemplate this frontier; standing on the island’s cliffs he is poised between his duty as king and husband and the pull of his own heart and mind.

Published over twenty years later in 1864, Enoch Arden also draws on the story of Odysseus. The title character is shipwrecked on a desert island where he remains alone for ten years, during which his wife, presuming her lost husband dead, remarries his old friend and has another child. For both Enoch and Ulysses, being on an island prevents his life from advancing in a favourable direction, but whereas the former is hindered purely by the constraints and obstacles set in place by nature and geography, the thing keeping the latter in place is his sense of kingly duty. Yet he swiftly delegates this to his son, Telemachus, after deciding that he “cannot rest from travel”.

Tennyson once again uses an island as the setting for a struggle between duty and desire in The Lady of Shalott. Sitting embowered by the silent isle, the title characters is cursed to weave a tapestry day and night, never leaving her turret or turning to glance out of her window at the scenes beyond. Her exposure to the outside world comes from “a mirror clear / That hangs before her all the year / [where] shadows of the world appear”. But the Lady of Shalott is “half sick of shadows”. She wants to see the willows and aspens, brooks and rivers, the castle of Camelot, and, above all, other people. And so, not knowing what the consequences would be, “she left the web, she left the loom, / She made three paces thro’ the room, / She saw the water-lily bloom / She saw the helmet and the plume, / She look’d down to Camelot”.

Interestingly, the curse is not yet ready to strike her down. Although her tapestry flies away and the mirror shatters, the Lady of Shalott is able to descend from her turret, get in a boat, inscribe it with her name and sail down the river towards Camelot singing her final song. It is not until just before “she reach’d upon the tide / The first house by the water-side, / Singing in her song she died”. On the water she finally realizes her fate; she is “Like some bold seër in a trance, / Seeing all his own mischance”.

Neither Ulysses nor the Lady of Shalott knows what will happen when they leave the safety of their islands, but the mundane routine of their daily lives means that they are willing to risk the dangers of the unknown for the chance to discover a new and more meaningful existence. For the Lady of Shalott, this lies in love, as it is the sight of two newly-weds that forces her to acknowledge her own loneliness, and then the appearance of the handsome Sir Lancelot that spurs her to abandon her loom, while Ulysses is driven by ceaseless curiosity and a longing for adventure. Only by leaving their islands and venturing out into unchartered waters can they can escape the state of limbo in which they are trapped.

The Lotos Eaters hints at the danger of failing to break out of such a state. Also based on the ancient tale of Odysseus, the poem ends with his crew’s decision to give up the oar and roam no more:

“They sat them down upon the yellow sand,

Between the sun and moon upon the shore;

And sweet it was to dream of Fatherland,

Of child, and wife, and slave; but evermore

Most weary seem’d the sea, weary the oar,

Weary the wandering fields of barren foam.

Then some one said, ‘We will return no more;’

And all at once they sang, ‘Our island home

Is far beyond the wave; we will no longer roam.”

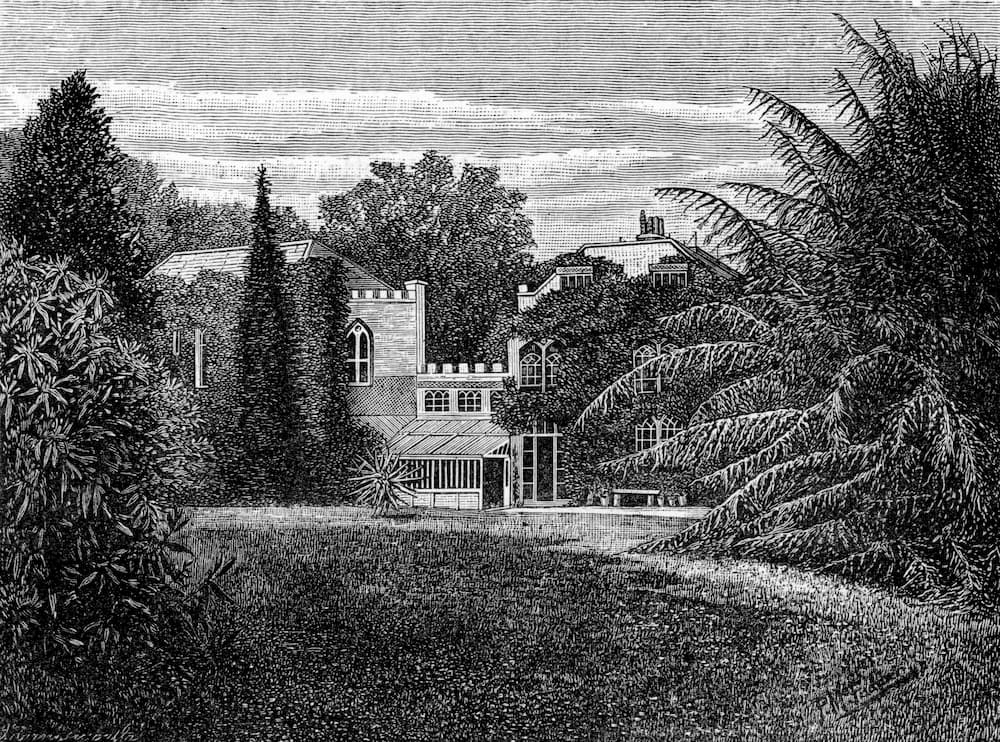

Farringford, I.O.W.

Despite the attractive imagery Tennyson conjures up to describe the island with its “charmed sunset”, “winding vale / And meadow” and trees “Laden with flower and fruit”, the reader is aware that remaining in such a place offers the men only a half-life. To stay there, although immediately gratifying, is to submit to a state of intoxication and stasis that will deny them the endless possibilities of “the wandering fields of barren foam” or the households that await them in their fatherlands. The same sense of oblivion permeates The Sea-Faeries, written in 1830, in which a group of mystical water-dwelling women implore passing sailors to remain with them on “blissful downs and dales” of their “islands free”. Its gentle repetition and irregular rhyme give the poem a hypnotic quality, as the sea-faeries entice the mariners with promises of an island paradise:

“We will sing to you all the day:

Mariner, mariner, furl your sails

For here are the blissful downs and dales,

And merrily merrily carol the gales,

And the spangle dances in bight and bay

And the rainbow forms and flies on the land

Over the islands free;

…

We will kiss sweet kisses, and speak sweet words:

O listen, listen, your eyes shall glisten

With pleasure and love and jubilee:

O listen, listen, your eyes shall glisten

When the sharp clear twang of the golden chords

Runs up the ridged sea.

Who can light on as happy a shore

All the world o’er, all the world o’er?

Whither away? listen and stay: mariner, mariner, fly no more.”

The invitation to furl the sails and stay on the island, with its songs, dances and natural beauties, is undoubtedly tempting. Like the lotus-eaters, the mariners of this poem are given the chance to escape the toil and hardship of normal life but, although Tennyson does not say so explicitly, it is clear to the reader that they will also be obliged to give up their pursuit of adventure, the expansion of their knowledge, and whatever family and human ties that they previously held.

While the island can offer pleasure, safety, and certainty, it ultimately demands a sacrifice; to live in such a liminal space denies one the opportunity to explore, take risks and test oneself. Despite the dream-like quality of much of Tennyson’s poetry, he is no escapist. His paradisiacal descriptions of exotic islands are inevitably tinged with an eerie sense of stagnation or danger that discourages his reader from over-indulgence in the idyllic imagery. It is particularly telling that two of his most memorable and treasured poems feature protagonists, quite opposite in their characters, who abandon the security and familiarity of their island-homes in order to experience the world to its fullest. Tennyson’s symbolic use of the island reminds us that, if we want to “drink Life to the lees”, we must sometimes set off into unchartered waters.

Main image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), oil on canvas, 1888, based on Tennyson’s poem. Contributor: IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Tennyson with his wife Emily Sellwood and sons Hallam (left) and Lionel. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Tennyson Down, Isle of Wight and its memorial cross to Tennyson. Credit: Steve Taylor ARPS / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Tennyson’s house Farringford on the Isle of Wight. Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Our edition of The Works of Alfred, Lord Tennyson can be found here

For more information, visit The Tennyson Society

Books associated with this article