A Literature of Cosmic Fear: H.P. Lovecraft

‘A Literature of Cosmic Fear’: An Introduction to H.P. Lovecraft

A blasted heath where nothing grows yet dead trees seem strangely animated; an abandoned well that glows with a colour that has no name; a disastrous expedition to Antarctica written by a survivor only to warn others to stay away; cathedral-sized buildings from before the dawn of mankind where the geometry doesn’t make sense; a pulp writer found dead at his desk, a look of frozen horror on his face; sailors discover a drowned city and half a world away an artist begins to sculpt a hideous figure while an architect goes mad; something not quite human breaks into an academic library to steal an unholy book; human brains are removed and placed in cannisters for transport to other worlds; the dead scream and a doctor vanishes; alien gods, ancient and terrible, dream beneath the sea… Enter, if you dare, the weird world of H.P. Lovecraft.

If you know Lovecraft’s fiction, there’s nothing you need from me. In fact, you almost certainly know it better than I do. Devotees of Lovecraft tend to be as encyclopaedic as he was, and several academics have forged successful careers out of interpreting his work, life, and letters. His ‘Cthulhu Mythos’ is pored over like a religious text, with references to it in Aleister Crowley’s Book of the Law and The Satanic Rituals by Anton LaVey and Michael A. Aquino. There are at least half a dozen books in print claiming to be the real Necronomicon of the ‘Mad Arab’ alchemist and necromancer Abdul Alhazred – another of Lovecraft’s inventions. Lovecraft’s influence over 20th century horror, supernatural and science fiction is vast, with symbols from his work spread out across popular culture, from death metal and Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen to Scooby Doo and Gravity Falls. There are currently over 30 films based on his stories, most notably the cult Re-Animator series directed by Stuart Gordon and Brian Yuzna (who also adapted Lovecraft’s 1920 story ‘From Beyond’), and many more that take their inspiration from him, such as Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead saga. In gothic literature, Lovecraft is the equal of Poe, to whom, he wrote, ‘we owe the modern horror-story in its final and perfected state’; he has no other peer. And their collective influence can be felt in the crimson line of great American horror writing that runs from Robert Bloch (who was a friend of Lovecraft’s), through Richard Matheson, to Stephen King. In the Geek Kingdom, if you want to suss out a so-called ‘horror expert’, check out what they have to say about H.P. Lovecraft.

But, as I said, I’m not preaching to the converted. You know how wild and engaging – not to say disturbing – these stories are, and chances are you own them all already. No, I’m talking to the folk who know the name, and probably some of the movies, and have maybe read a few of the stories in anthologies without committing to the corpus. As we swing around to Halloween again, in a world that becomes more ominous, pestilential, and apocalyptic by the year, I reach out, like the creatures of the Necronomicon in Evil Dead and whisper, ‘Join us.’

It is not just in imagination and statue that Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890–1937) matches Edgar Allan Poe. He also shares the tragic but not unfamiliar distinction in literature of not being widely read, recognised, or renumerated in his own lifetime. His publication history was limited almost entirely to amateur and pulp magazines, leaving him virtually unknown outside a small but dedicated following of other pulp writers, and he was never able to support himself financially by writing. Also, like Poe, he was physically frail and emotionally vulnerable, and died far too soon.

H.P. Lovecraft

Lovecraft was born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1890 – where he remained for the majority of his life – the only child of wealthy parents, his mother, Susie, being the daughter of the property and mining baron, Whipple Van Buren Phillips. When Lovecraft was two, his father was committed to Butler Hospital (a private mental institution) after a psychotic breakdown most likely caused by late-stage syphilis. He never recovered and died in 1898. Lovecraft was raised in his maternal grandparent’s home, where he was doted on by his grief-stricken mother. His grandmother died when he was six, and he later wrote that the mourning process ‘terrified’ him. Lovecraft’s grandfather was a cultured Anglophile who epitomised the east coast ‘old money’ set. He encouraged his grandson to read widely, introducing him to classical and English literature as well as gothic fiction and the Arabian Nights, guilty pleasures which he adapted into bedtime stories for the boy. As business took his grandfather away often, the pair began a thriving correspondence, a habit Lovecraft retained into adulthood, often with people deemed close friends he never met in person, writing an estimated 100,000 letters over his short life. As an infant, Lovecraft was incredibly literate; this interest in words was soon supplemented by a passion for science, particularly astronomy, and by age twelve he was contributing to the Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy. Ill health often kept him out of school, and he was principally educated by family, private tutors, and a lot of self-directed learning, making him idiosyncratically brilliant but also shy, withdrawn, and socially awkward.

The turn of the century saw the gradual erosion of the family’s wealth, until Whipple’s business collapsed in 1904. Whipple died a few months later and, unable to maintain the family home, Lovecraft’s mother moved herself and her son into a small duplex house, letting the last of the servants go and living off a modest income generated by the remnants of the Phillips estate, which was soon shrunk further after some disastrous investments by her brother. Lovecraft later wrote that this was the darkest period of his life, and that only his scientific studies and curiosity prevented him from taking his own life. His relationship with his mother was close but complex. Much of his ill-defined ‘health problems’ were ‘nervous disorders’ that were almost certainly exacerbated by his mother’s cossetting. (Later, when America joined the Great War, she brought all her remaining social influence to bear to keep her son out of the Army and the National Guard, though he wanted very much to volunteer.) In 1908 he suffered some sort of breakdown which interrupted his high school education and prevented his planned entry to Brown University – he never took a degree. ‘I could hardly bear to see or speak to anyone,’ he later wrote, describing his anxiety and depression, ‘and liked to shut out the world by pulling down dark shades and using artificial light.’ His mother’s constant remarks about his ‘hideous’ appearance also appears to be the root of a lifetime of body dysmorphia, although when neighbours believed that the two frequently and loudly fought, what they were hearing was in fact Lovecraft and his mother charging about the house performing Shakespeare. Susie eventually followed her husband into Butler Hospital in 1919, no longer recognising people she knew and beset by visions of ‘weird and fantastic creatures that rushed out from behind buildings and from corners at dark.’ Lovecraft visited her regularly until her death there in 1921 and once more considered suicide, though his increasing involvement with the amateur writing scene pulled him through. Free from Susie’s influence he become notably more outgoing, attending literary readings and gatherings, and forming friendships for the first time in his life. He even managed a relationship with the pulp fiction writer and amateur publisher, Sonia Greene, whom he married in 1924 although his surviving family did not approve. (Sonia was Jewish.) He moved to New York with Sonia, where he met Edwin Baird, the inaugural editor of the pulp magazine Weird Tales, in which many of his best stories were subsequently published. Work took Sonia away much of the time, leaving Lovecraft alone and despondent. In his short story ‘He’ (Weird Tales, 1926), the anonymous narrator deeply regrets his move from New England to New York City: ‘I had looked for poignant wonder and inspiration’ but ‘I had found instead only a sense of horror and oppression which threatened to master, paralyze, and annihilate me.’ Lovecraft returned to his beloved Providence at the end of the year, never to leave again, and he and Sonia eventually separated in 1933.

Lovecraft had begun writing fiction in 1904, the year of his family’s financial collapse, with ‘The Beast in the Cave’, a short story about a man lost in the Mammoth Cave in Kentucky with a tidy twist at the end in which the influence of Poe is apparent. This was published in The Vagrant in 1918, an independent magazine produced by and for amateur journalists. This was followed by ‘The Alchemist’ in 1908 (which saw print sooner, in the United Amateur in 1916), the tale of a fatal curse passed down through generations, again concluding with a crisp gothic epiphany. This was the era of the pulp magazines – christened after the cheap wood pulp paper on which they were printed – which the young Lovecraft consumed along with his more formal literary and scientific reading. His way into this medium as a writer was through the letters pages, to which he contributed many observations and critiques, applying the tools of literary criticism to popular fiction, a critical practice decades ahead of academic literary scholarship. In 1911, a letter from Lovecraft appeared in the pulp magazine Argosy criticising one of their regular contributors, Frederick J. Jackson, sparking a feud that the editors gleefully published between both writers and their supporters. This spirited critical dialogue attracted the attention of Edward F. Daas of the United Amateur Press Association, who invited both men to join. Amateur press associations (APAs) were the herald of fanzines, enabling readers and contributors to share and discuss their common interests in a single forum; these were the bulletin boards and social media of their day, often associated with genre film and fiction. Lovecraft threw himself into amateur journalism, having something of an upper-class disdain for commercial writing, becoming the chairman of the UAPA Department of Public Criticism in 1914, then vice-president of the association in 1915 and president in 1917. This gave Lovecraft an outlet for his fiction, including ‘The Tomb’, another Poe-like tale of a young man obsessed with a mausoleum, and ‘Dagon’ (both 1917), which foreshadows ‘The Call of Cthulhu’ (Weird Tales, 1928), introducing many of the concepts and themes that would dominant his mature fiction. (The ‘Esoteric Order of Dagon’ later turns up in Lovecraft’s 1931 novella The Shadow over Innsmouth.) He also wrote his first science fiction story around this time, ‘Beyond the Wall of Sleep’ (1919), inspired by his lifelong fascination with the power of dreams, and positing a form of long-range telepathic communication that feels like the origin of the horrible connection between earth and the alien outpost of Yuggoth in the victims of his famous later stories ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’ (Weird Tales, 1931) and ‘The Haunter of the Dark’ (Weird Tales, 1936). Lovecraft’s science fiction would reach its creative zenith with the beautiful ‘The Colour Out of Space’ (Amazing Stories, 1927), although as the Old Ones on one level represent the threat of alien invasion, it could be argued that the entire Cthulhu Mythos is broadly sci-fi.

It was likely shyness rather than snobbery that kept Lovecraft in the amateur publications, just as his enthusiasm for science and literature and his undoubtedly brilliant intellect was shared with friends through endless and lengthy correspondence, never in person. Then he graduated to the gaudy and cheap pulp magazines, which were at the time largely dismissed as throwaway popular culture and were not made to last. These were where many notable 20th century genre authors did their apprenticeships, such as Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Raymond Chandler… and after the war, Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and Michael Moorcock, all of whom moved on to bigger and better things. Perhaps Lovecraft would have done the same, had he lived, but while active he showed no sign of wanting an agent or a more mainstream publisher. There is something tragic and beautiful about the quality and scholarship of his work, all given away either for free or for tiny one-off fees to a small and temporary audience. One is left with a sense that were Lovecraft writing today he would just be posting it all on Reddit.

‘Herbert West – Reanimator’ was serialised in another amateur publication, Home Brew, in 1922, Lovecraft receiving five dollars an instalment. In this satiric homage to Frankenstein (packed with allusions to Shelley and Coleridge), an unnamed doctor relates the events leading up to the disappearance of his friend and colleague, Herbert West, a driven and narcissistic scientist whose ‘reagent’ serum can return the dead to life. The story relates a series of increasingly gruesome experiments (reaching their peak when the pair become battlefield medics in World War One), in which the subjects usually attempt to bury themselves before becoming insanely violent. Lovecraft did not much like the work, and his academic followers have largely decried it as trivial, yet it spawned one of the most iconic horror franchises of the 1980s and is probably the Lovecraft story with most name-recognition outside the base. West, as played by the actor Jeffrey Combs in Re-Animator (1985), Bride of Re-Animator (1990), and Beyond Re-Animator (2003), was voted 42nd in Empire’s 100 Best Movie Characters, which described him as ‘one of cinema’s greatest mad scientists.’ In Herbert West – Reanimator, Lovecraft also pretty much invented the modern zombie, as mindless, amped-up, and aggressive. Lovecraft’s stories have often proved difficult to adapt to the screen; it is perhaps the relative simplicity of this one that made the movies so brilliant. There is also a gallows humour to the original text that translates very well to film. Lovecraft, when he wanted to, could be darkly funny.

Inspired by attending a talk in Boston by Lord Dunsany in 1919, considered to be one of the founders of modern literary fantasy and one of Lovecraft’s heroes, he began his ‘Dream Cycle’ of stories loosely connected by the ‘Dreamlands’, a vast alternate dimension that could only be entered through dreaming. This concept of another world pushing against the boundaries of our perceived reality found its full intellectual potential in the beginnings of what we now know as the Cthulhu Mythos, in which Lovecraft developed his philosophic theory of Cosmicism, in which humanity is insignificant in the face of an infinite, eternal, and godless universe. As he wrote to Edwin Baird: ‘Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.’

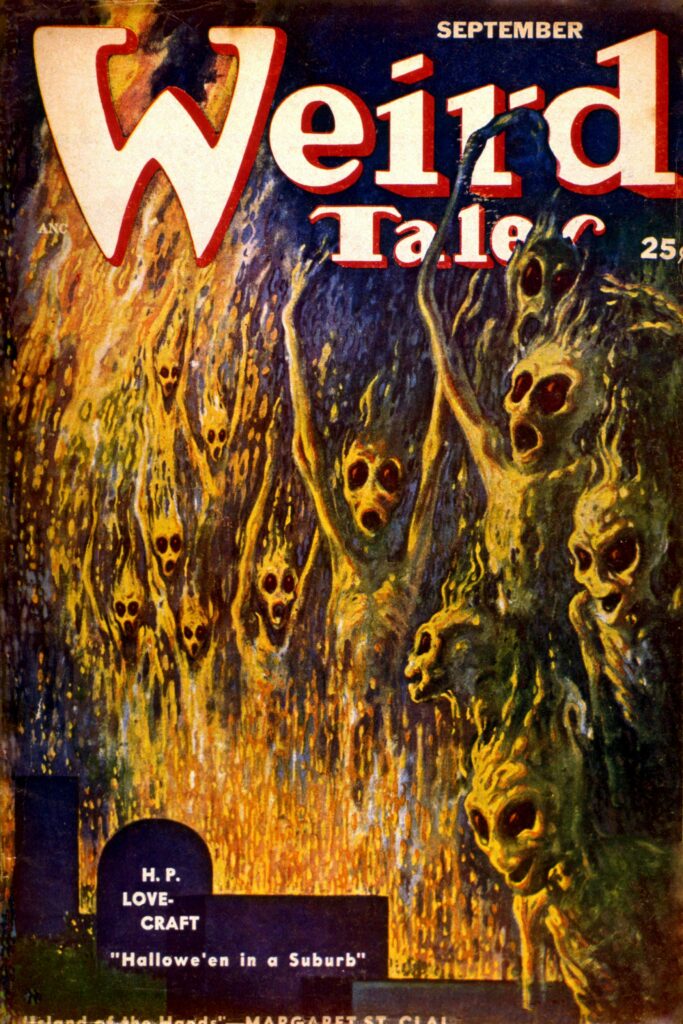

Weird Tales

The ‘Cthulhu Mythos’ is a mythopoeia – a fictionalised mythology – and fictional universe in which the earth was once ruled by extra-terrestrial/extra-dimensional beings, the ‘Great Old Ones’, representing ‘old and unhallowed cycles of life in which our world and our conceptions have no part.’ Starting with the title-deity of his prose-poem ‘Nyarlathotep’ (1920), there are many ‘Old Ones’, ‘Deep Ones’, ‘Elder Things’, and ‘Outer Gods’ in Lovecraft’s mythology, though it is the ‘Great God Cthulhu’ which has struck the cultural nerve and whose name has transcended the stories which initially contained him, becoming common currency in the discourse of modern horror. Cthulhu is introduced in the ‘The Call of Cthulhu’, published in Weird Tales in 1928. Beginning as a ‘nameless monstrosity’, the cult and image of Cthulhu is built up as the story’s narrator, Francis Wayland Thurston, details the trail of research, folklore, and witness testimony that leads him to a terrible insight that has killed many men, driven more mad, and which he wishes he could erase from his memory:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

In Lovecraft, ignorance is the only bliss, while true knowledge of the universe brings only fear and regret, often to the point of insanity. Following Poe, the horror of Lovecraft’s fiction is psychological and internal, but also external through genuine physical threat from Old Ones and their minions. As Lovecraft’s monsters are always protean, vague, and obscure – his style both adjectival and abstract – we are left with a sense of Cthulhu composed of ‘simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature’ with vicious claws and a ‘pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings.’ The creature is mountainously large and is accompanied by ‘a stench as of a thousand opened graves’ and ‘a sound that the chronicler would not put on paper.’ More essay than story (there is not a scrap of dialogue), Thurston’s narrative reads like a piece of investigative journalism that got way out of hand. It is this sense of realism that makes the Cthulhu Mythos so compelling. Lovecraft’ elaborate world building is a masterpiece of pseudobiblia, in which fiction is presented as non-fiction, citing equally fictitious texts from letters and newspaper articles to academic papers and the occult grimoire Necronomicon, which also has its own ‘History’, written up by Lovecraft in 1927.

Thurston is a dilettante who fancies he may be onto a great anthropological discovery, his interest piqued by certain artefacts found in a locked box belonging to his recently deceased grand-uncle, a professor of Semitic languages at Brown University. Instead, he is burdened with ‘the single glimpse of forbidden eons which chills me when I think of it and maddens me when I dream of it’, a ‘dread glimpse’ of ‘unhallowed blasphemies from elder stars which dream beneath the sea.’ Lovecraft called this ‘a literature of cosmic fear’. The common theme of this strange canon is one of forbidden or dangerous knowledge that invariably destroys those that stumble upon, seek, or possess it, and of great and terrible forces waiting on the edge of our perception, always probing, always pushing, seeking a way in. As Daniel Upton, the luckless narrator of ‘The Thing on the Doorstep’ (Weird Tales, 1937), explains: ‘There are horrors beyond life’s edge that we do not suspect, and once in a while man’s evil prying calls them just within our range.’ In the gothic sense, this is not unlike the Swedenborgianism of J.S. Le Fanu, in which some unfortunates tune into the spirit world and attract the attention of things they should not. Lovecraft is just doing it on a vaster, secular, and more scientific scale. Similarly, the narrator of At the Mountains of Madness (Astounding Stories, 1936), warns that: ‘It is absolutely necessary, for the peace and safety of mankind, that some of earth’s dark, dead corners and unplumbed depths be left alone; lest sleeping abnormalities wake to resurgent life, and blasphemously surviving nightmares squirm and splash out of their black lairs to newer and wider conquests.’ These immensely powerful, amoral, and terrifying beings are now remembered as gods only by secret and evil cults who strive to facilitate their new reign. The Old Ones dream in a deathlike sleep beneath the earth, sea, and sky, their return prophesised in the Necronomicon:

That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange eons even death may die.

As they sleep, their minds reach out to touch sensitive dreamers, and accidental discovery or deliberate invocation can bring them out of hibernation. The alien pantheon and its occult texts feature across many if not most of Lovecraft’s stories, with the above couplet frequently repeated, connecting each self-contained narrative in a single and epic story arc that forms the backbone of his most significant work after his relatively conventional gothic juvenilia. This sense of continuity is further strengthened by Lovecraft’s repeated use of fictionalised New England settings such as Miskatonic University, Arkham, Dunwich, and so forth, building on the evocative history and atmosphere that evolved from the Puritan Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies and the witch mania of Salem, land that seems to grow gothic writers from Poe and Hawthorne to Lovecraft and King.

The constant threat of the howling void suits Lovecraft as both an atheist (his religious views are summarised in his 1922 essay ‘A Confession of Unfaith’) and a depressive, while tapping into post-Nietzschean and modernist interpretations of the human condition without the old Victorian certainties, most notably a belief in a god that orders the universe, and in whose patriarchal image society is structured, from our fathers up to prime ministers and kings, via the mediating authority of teachers, policemen, and priests. To the existentialist, once they figure out that it is worth continuing to exist, this can be a liberating state of mind. But it can also be terrifying, offering an unwanted sense of proportion in a vast, empty, and indifferent universe, life no more than an invisible dot on an invisible dot, without God, point or purpose. In literature, Joseph Conrad’s response was the final words of Mr Kurtz in Heart of Darkness – ‘The Horror! The Horror!’ – while T.S. Eliot wrote ‘The Waste Land’ and Victorian literary and artistic realism died on the Western Front. Lovecraft just pushes it a bit further with the three-lobed burning eye and the screaming tentacles of retribution. He could be argued to be allegorising the same sense of spiritual emptiness that haunted humanity after the Great War through his chosen medium of popular and genre fiction, coupled with his belief that human civilisation was in a state of decay. Though his Cosmicism appears notionally pessimistic, Lovecraft considered himself to be more philosophically and psychologically neutral, which would put him closer to the camp of existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. His was a stance of scientific detachment, and he styled himself a ‘cosmic indifferentist’.

Lovecraft referred to this mythic cosmology as his his ‘Yog Sothothery’. (‘Yog-Sothoth’ is the progenitor of Cthulhu and Hastur the Unspeakable, and the father of Wilbur Whateley in The Dunwich Horror.) The term ‘Cthulhu Mythos’ was coined by Lovecraft’s friend and disciple, the writer August Derleth, one of the ‘Lovecraft Circle’ of pulp writers that also included Clark Ashton Smith (whose work, wrote Lovecraft, was unparalleled ‘in sheer daemonic strangeness’), Robert E. Howard (creator of Conan the Barbarian), Frank Belknap Long, Henry Kuttner, Henry S. Whitehead, Fritz Leiber (who coined the term ‘sword and sorcery’), and the young Robert Bloch (the author of Psycho). Through his voluminous correspondence, Lovecraft encouraged these like-minded writers, bringing them together, sharing publishing contacts, and making referrals within the pulp magazine world. He also championed the swapping of fictional worlds and motifs among the group’s work, leading to the glorious exchange between Robert Bloch’s ‘The Shambler from the Stars’ (Weird Tales, 1935), and Lovecraft’s final story, ‘The Haunter of the Dark’ (Weird Tales, 1936), in which the authors gleefully murder each other in print. Thus did the Cthulhu Mythos grew out of the original ‘Yog Sothothery’, as circle members, most notably Derleth, continued to write in the Lovecraftian universe after his death from cancer of the small intestine in 1937. With another Weird Tales writer, Donald Wandrei, Derleth founded Arkham House in 1939 to collect and publish Lovecraft’s fiction, virtually none of which had seen print outside the pulps in his lifetime. Calling himself a ‘posthumous collaborator’, Derleth also wrote a number of stories based on notes and fragments left by Lovecraft, further widening the Cthulhu Mythos. Derleth’s efforts not only kept Lovecraft’s legacy alive but ensured that his reputation grew by collecting the stories and making them accessible to a wider audience until the academics began to take note in the 1970s, and a fully-fledged revival and rehabilitation commenced, followed by the cult movies. They have been moaning about Derleth’s stewardship of the early Lovecraftian legacy and debating the meaning of the stories ever since, applying similar literary forensics to the academic ink spilled over writers like Poe and Kafka. Largely ignored in his own lifetime, Lovecraft is probably one of the most written-about writers in the history of the gothic.

Thankfully for us, Lovecraft also left his own views on the subject, in his 1927 essay ‘Supernatural Horror in Literature’, a stunning piece of literary history and criticism characteristically hidden in an obscure magazine (The Recluse, which only lasted one issue), but which Derleth cannily reprinted in The Outsider and Others (1939), the first Arkham House publication and decent Lovecraft anthology. Lovecraft uses several genre labels interchangeably to define the tradition to which he belongs – ‘supernatural’, ‘fear-literature’, ‘gothic’, ‘horror’, ‘terror-literature’, ‘spectral literature’ – but the word he uses most of all is weird. ‘Weird Tales’ are a synthesis of horror, fantasy, speculative and science fiction, and the genre persists to this day in ‘New Weird’ and ‘Slipstream’ fiction. They do not do the traditional gothic archetypes like ghosts, vampires, werewolves, and vengeful revenants, at least not in a traditional way, hence the recurring symbol of the tentacle in the work of Lovecraft, William Hope Hodgson, Clark Ashton Smith, E.F. Benson, and M.R. James, an appendage not associated with the monsters of the European gothic. They must also evoke a sense of the numinous, arousing deep, almost spiritual emotion; a feeling of mystery and awe:

The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain – a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.

In charting the evolution of the weird tale, Lovecraft begins with prehistory and the opening assertion that ‘The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.’ From this he moves through primitive superstition and stories told around Neolithic campfires, through Graeco-Roman myths and Dark Age folklore, European ghost stories, the rise of the gothic novel, late-Victorian horror, the ’weird tradition’ in Britain and America (Poe gets a whole chapter), and, finally, the ‘modern masters’ of the form: Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany, Arthur Machen, and M.R. James. Lovecraft celebrates the ‘genuineness and dignity of the weirdly horrible tale as a literary form’ which rightly flies in the face of ‘a naïvely insipid idealism’ in popular literature which ‘deprecates the æsthetic motive and calls for a didactic literature to “uplift” the reader toward a suitable degree of smirking optimism.’ (He might as well have been describing contemporary publishing, in which feel-good ‘uplift’ fiction is now an official and popular genre.) It also requires a better class of reader, because ‘The appeal of the spectrally macabre is generally narrow because it demands from the reader a certain degree of imagination and a capacity for detachment from everyday life.’ So there. The range of Lovecraft’s scholarship and influences also demonstrates the way in which his writing unites the forms of the American and the British weird, gothic, horror… call it what you will, as well as science fiction. In critiquing those he admired most, he also provided the key to his own complex and esoteric vision.

Finding your way into Lovecraft’s opus can be a little daunting. There’s a lot of it, and by contemporary standards his prose style is dense, with a focus often on emotional states, backstories, and observation over action and dialogue which makes his voice intense yet quite passive at times, like one of his major influences, Lord Dunsany. It is a written style that takes time to tune in to, but once you click, I guarantee you will not be able to put the book down. And the ideas, the imagination, the breath-taking conceptual range… there’s little else in the discourse of modern horror that even comes close. Let’s just say there’s a reason fans of Lovecraft tend to be quite obsessive. Everyone will have their own favourites, and you can, of course, just work through all the anthologies, which is what you’ll do once you’re hooked. In finding a way in, you could do worse than start with a selection of short stories from the 1920s, when Lovecraft found his form after his early fiction, which could be quite stiff and immature (though ‘Dagon’ is worth a look), such as ‘The Outsider’ and ‘The Rats in the Walls’. ‘The Call of Cthulhu’ and ‘The Colour out of Space’ are essential, and although ‘Herbert West – Re-Animator’ is atypical and frequently disregarded by critics, it is a lot of fun. Then choose a selection from the 1930s, starting with ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’ (for Alan Moore nuts, this is the source for ‘What Ho! Gods of the Abyss’, a League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Black Dossier story which memorably blends the styles of Lovecraft and P.G. Wodehouse); and ending up at Lovecraft’s final story, ‘The Haunter of the Dark’, in which a pulp writer based on Robert Bloch gets more than he bargained for after exploring a derelict church that the locals steer well clear of. You should then be ready for the novellas, all key texts in the Cthulhu Mythos: The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, The Shadow over Innsmouth, The Dunwich Horror, and At the Mountains of Madness. After that, just pick and choose, or spend a darkly pleasurable few months reading the entire collections and contemplating your position in the cosmos. You are now in the club, and there’s no turning back. Once known, these terrible truths cannot be unknown, so enjoy!

Lovecraft’s stories are rich, vivid, and twisted, his prose always reaching for the perfect series of words to describe that which is indescribable. Ultimately, Lovecraft saw us as alone and insignificant in an ancient, vast, and hostile universe, subject to the whim of malevolent forces that we will never understand and probably shouldn’t. Looking at the world right now, this epic dumpster fire of violence and chaos, who are we to argue with him?

Main image: Still from the 1963 Roger Corman film The Haunted Palace, based on Lovecraft’s The Case of Charles Dexter Ward Credit: TCD/Prod.DB / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Cover of Weird Tales September 1952. Artwork of Demons by Virgil Finlay Credit: Charles Walker Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

The Horror in the Museum: Collected Short Stories Volume 2

H.P. Lovecraft

The Whisperer in Darkness: Collected Stories Volume I

H.P. Lovecraft

The Haunter of the Dark: Collected Short Stories Volume 3

H.P. Lovecraft