The Gothic Life of Edgar Allan Poe

Stephen Carver looks at the life of Edgar Allen Poe, probably the most innovative and influential figure in 19th-century American literature.

When he died in Baltimore on Sunday, October 7, 1849, Edgar Allan Poe, probably the most innovative and influential figure in 19th-century American literature, was raving and destitute. He was 40 years old.

Four days before, he had been found in the street outside the Gunner’s Hall public house ‘in great distress, and in need of immediate assistance by a passer-by called Joseph Walker, a compositor on the Baltimore Sun. Poe was coherent enough to ask that a friend who lived in the area, Dr Joseph Snodgrass, be contacted and the doctor, accompanied by Poe’s uncle, conveyed by the then delirious author to the Washington Medical College, where he died without ever fully coming to his senses. The circumstances leading up to Walker’s intervention, therefore, remain a mystery to this day, as does the reason for him being in Baltimore in the first place – he lived in New York, regularly travelling to Richmond, Virginia, where he intended to relocate to marry his childhood sweetheart. His rescuers assumed he was at the end of a savage drinking binge.

Like a character in one of his own mysteries, Poe, who was a dapper dresser as a rule, was wearing clothes so rustic and shabby that his attending physician, Dr John Moran, did not think they were his. The only thing of note Poe said in the hospital was to repeatedly call out the name ‘Reynolds’ the night before he died. Whether he was asking for this person or denouncing his killer, nobody knows. Although his medical records and death certificate have been lost, newspapers at the time reported his cause of death as ‘congestion of the brain’ or ‘cerebral inflammation’, terms often euphemistically applied to drinking yourself to death. This has been interpreted by modern biographers as most likely some sort of brain lesion, the cause of which remains unclear. This could have resulted from a long-standing condition growing worse over time, meningitis, or a more recent head trauma. It is known Poe suffered from heart arrhythmia which was exacerbated by stimulants, so a heart attack or stroke seem more than possible.

Although the evidence is largely circumstantial, a nonetheless compelling popular theory holds that Poe was the victim of ‘cooping’, then a common form of electoral fraud in America in which vulnerable people were grabbed off the street by ‘cooping gangs’ and coerced into voting for a specific candidate as many times as they could. (The ‘coop’ was a place of improvised incarceration where the victim was plied with drink and often beaten into cooperation. Death was not uncommon.) They were escorted out in different clothes and disguises to vote, and October 3 had been a local election day in Baltimore. Gunner’s Hall was a polling station, and one of the three presiding election judges was Henry R. Reynolds. On the other hand, Poe, in his addled state, might have just as easily been fixating on the newspaperman and explorer Jeremiah N. Reynolds, who sometimes lent him money. This Reynolds was the author of the ‘Address on the subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and the South Seas,’ published in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1837 with ‘Critical Notes by Edgar A. Poe, Editor’, and which was likely to have been the inspiration behind Poe’s only completed novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, published in 1838. Nonetheless, as John Evangelist Walsh argues in his book Midnight Dreary: The Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe (2000): ‘Present in the same room as Poe on October 3rd at Ryan’s place [Gunner’s Hall], only days before he began in his delirium to call out the name, was an actual, flesh-and-blood Reynolds.’ But, like the identity of Jack the Ripper, we will never know for sure. All we can say with any certainty is that Poe’s death, like his life, was both tragic and dramatic.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1809, Edgar Poe was the second child of two professional actors. David Poe Jr. was a Baltimore man who had forsaken his legal studies for the stage but had a little apparent aptitude for the craft. His wife, Eliza, an emigrant from London, was notably more talented, versatile, and popular. Despite Eliza’s apparent success, especially in Boston, a city she loved, money was a constant worry. David turned to drink and abandoned the family when Poe was still a baby and Eliza was pregnant with their third child. Eliza, still acting, started showing signs of tuberculosis early in 1811, and by the end of the year, she was dead, shortly to be followed by her estranged husband. Her three children were split up. Eldest son William Henry went to his paternal grandparents in Baltimore, while Edgar and his younger sister Rosalie were fostered by family friends in Richmond, Virginia; Rosalie by William and Jane Scott Mackenzie, and Edgar by John Allan, a Scottish merchant, and his wife, Frances. Mrs Allan was childless and doted on Poe. Edgar Poe became Edgar Allan Poe, although he was never formally adopted. The Allans returned to Scotland between 1815 and 1820, and Poe was educated first at a grammar school in Ayrshire, then a boarding school in Chelsea and, finally, the Reverend John Bransby’s Manor House School in Stoke Newington, an experience that would later provide the setting for his short story ‘William Wilson’.

After the family returned to Richmond, John Allan became a wealthy man through a large inheritance. Poe began courting a neighbour’s daughter, Sarah Elmira Royster, in 1825 when she was 15 and he was 16. Her father did not approve of Poe because of his background as the poor orphan child of travelling players and when Poe began studying at the University of Virginia in 1826, Royster intercepted and destroyed his letters to Sarah. Despite their secret engagement, Sarah assumed Poe had deserted her and married a local businessman the following year. While at university, Poe’s relationship with Allan degenerated over money. Allan was not adequately funding his studies as agreed, and Poe’s attempts at increasing his income by gambling predictably ended in disaster. The relationship fractured and Poe was forced to drop out because of his debts, despite his brilliant academic record. Feeling unwelcome in Richmond and reeling from Sarah’s marriage, Poe travelled to Boston, which his birth mother had impressed upon him was a city of her ‘best and most sympathetic friends’. Poe had begun to write poetry seriously at university and he privately published the slim volume of the Byron-inspired Tamerlane and Other Poems in Boston in 1827. Only 50 copies were printed, all of which fell stillborn from the press, although Poe was encouraged to keep writing after a positive review from the influential literary critic John Neal. Poe’s second book Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems (Baltimore, 1829) is dedicated to Neal in gratitude.

Having failed to secure steady employment, Poe enlisted in the United States Army under an assumed name, lying about his age. At 18, he had no training in a trade or a profession, but he had been a lieutenant of the Richmond youth honour guard. Allan had no idea where his foster son was, but wrongly guessed he had gone to sea. Poe’s time at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island provided the setting for ‘The Gold Bug’ while its beaches would later welcome the travellers of his ‘Balloon-Hoax’.

After two years, Poe, now an Artillery Sergeant Major, revealed his identity to his commanding officer. It was decided he would be discharged if he could reconcile with his foster family, but Allan was unresponsive until his wife died, which seemingly softened his stance. Allan agreed to support Poe in seeking an early discharge to enter the West Point Military Academy, and Poe enrolled as a cadet in 1830, with a view to becoming an officer and a gentleman, which was his best shot at achieving some sort of social rank given his background. John Allan remarried soon after, and once again he and Poe quarrelled, again over money – the wealthy Allen remained a cheapskate creating the same problems for Poe he had faced at university – but also over Allan’s legitimate children, products of affairs during his marriage to Frances. This time Allan disowned Poe. Out of money, Poe ended his military career in 1831 by ceasing to follow orders and getting deliberately court-martialled. He was dishonourably discharged for dereliction of duty. He then went to New York to publish his third book, Poems, which was funded by donations from his fellow cadets and is dedicated to them. They probably expected the satirical poems about army life they associated with Poe rather than the gothic romanticism he delivered, which included early versions of ‘To Helen’, ‘Israfel’, and ‘The City in the Sea’, all prototypes for the themes that would preoccupy his later literary output. Still unrecognised as a poet, Poe returned to Baltimore to stay with his widowed aunt Maria Clemm, her daughter Virginia Eliza, his invalid grandmother Elizabeth Cairnes Poe, and his brother. Henry, following in his father’s footsteps, was struggling with alcoholism, and succumbing to tuberculosis. He died in August 1831.

Life was hard for the family, but there was a lot of love in the household, especially between Poe and his younger cousin, Virginia. Poe committed to writing for a living and began to produce short fiction, which was more commercial than poetry. This was not a great time to be a writer in America. Publishers saw little need to pay native authors for their work when the absence of copyright laws meant they could freely pirate work by English writers. As in England, new printing and paper-making technology created a periodicals boom, although many did not last and proprietors frequently paid contributors late, less than agreed or not at all. Poe nonetheless got five ‘grotesques and farces’ into literary magazines in 1832, winning the Baltimore Saturday Visitor short story competition with ‘MS. Found in a Bottle’ the following year. Judges were unanimous in their praise of Poe’s style and originality compared to the trite melodrama of most popular fiction, and the only reason he didn’t win the poetry prize for ‘The Coliseum’ as well was that the judges did not wish to be accused of favouritism. The lawyer and inventor John H. B. Latrobe later recalled meeting the young author when he visited the judges to thank them and collect his prize:

He was, if anything, below the middle size, and yet could not be described as a small man. His figure was remarkably good, and he carried himself erect and well, as one who had been trained to it. He was dressed in black, and his frock coat was buttoned to the throat, where it met the black stock, then almost universally worn. Not a particle of white was visible. Coat, hat, boots and gloves had very evidently seen their best days, but so far as mending and brushing go, everything had been done, apparently, to make them presentable. On most men, his clothes would have looked shabby and seedy, but there was something about this man that prevented one from criticizing his garments … Gentleman was written all over him. His manner was easy and quiet … The expression on his face was grave, almost sad, except when he became engaged in conversation when it became animated and changeable.

Latrobe was speaking at the unveiling of Poe’s Memorial Grave Monument in Baltimore in 1875.

Latrobe had concluded: ‘The prize for this story, the public recognition that it brought and the lifelong friendship it generated between Poe and literary patron [John Pendleton] Kennedy helped to launch Poe on his brilliant career. He left Baltimore in 1835 to become editor of the Southern Literary Messenger.’ But between the dream and the reality falls the shadow, as they say. Despite public recognition as a writer, Poe couldn’t find a publisher for his Collected Tales and continued to struggle financially. Kennedy, a novelist, lawyer and politician, introduced Poe to Thomas W. White, editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond, and he was glad to accept an assistant editorship in 1835, although he was fired for intemperance after a few weeks. White later relented, and Poe became editor in everything but name, also contributing poems, book reviews, critiques, and stories. In the two years he worked on the paper, circulation increased from 500 to 3,500. Despite this, his wages never rose higher than $10 a week. On May 16, 1836, he and Virginia were married in Richmond, with a witness falsely attesting the bride’s age as 21. She was, in fact, 13; Poe was 27.

For reasons that remain unclear, Poe left the Messenger in January 1837. Having still failed to publish his Collected Tales, Poe was advised by the publisher Harper & Brothers to try his hand at a novel, which was deemed more commercial. The result was The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, published by Harpers in July 1838, and presented as an account by Pym himself. If you’ve not read this remarkable book, its original and lengthy subtitles will give you the flavour:

Comprising the Details of Mutiny and Atrocious Butchery on Board the American Brig Grampus, on Her Way to the South Seas, in the Month of June 1827. With an Account of the Recapture of the Vessel by the Survivors; Their Shipwreck and Subsequent Horrible Sufferings from Famine; Their Deliverance by Means of the British Schooner Jane Guy; the Brief Cruise of this Latter Vessel in the Atlantic Ocean; Her Capture, and the Massacre of Her Crew Among a Group of Islands in the Eighty-Fourth Parallel of Southern Latitude; Together with the Incredible Adventures and Discoveries Still Farther South to Which That Distressing Calamity Gave Rise.

Now recognised as a masterpiece that had a significant influence on the later work of R.L. Stevenson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, contemporary reviews of Arthur Gordon Pym were less than complimentary, often decrying its excessive violence and the deceit of the fake memoir. A few months later, the novel was printed in London without Poe’s permission. He received not a penny for it, but this publication initiated the British interest in Poe’s fiction.

Desperate for money, Poe accepted another assistant editorship at Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine in Philadelphia (who had given Pym a rotten review), again for $10 a week. Disheartened by his novel’s reception and aware that his theories of art did not lend themselves to long narratives, Poe returned to short fiction. His next book was the iconic Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, published in two volumes by Lea & Blanchard of Philadelphia in 1840, who were eager to capitalise on the success of ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (published in Burton’s the previous year). Poe was not offered royalties, his only payment being 20 free copies of the book. Both volumes collectively comprise 25 stories, including such famous and beloved tales as ‘William Wilson’, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, ‘Berenice’, ‘Ligeia’, and the wonderful satire on the British Regency Tale of Terror, ‘The Psyche Zenobia’ (AKA ‘How to Write a Blackwood’s Article’) and its companion ‘The Scythe of Time’ (later retitled ‘A Predicament’) which moves from the theory to the practice, as the hapless wannabe author ‘Miss Psyche Zenobia’ (in reality one Suky Snobbs) attempts to record her ‘sensations’ – as advised by publisher William Blackwood – while being slowly decapitated by the hands of a giant clock. (‘Sensations are the great things after all. Should you ever be drowned or hung, be sure to make a note of your sensations – they will be worth to you ten guineas a sheet.’) Poe would later incorporate and develop features from this genre in his own tales. The influence of William Maginn’s ‘The Man in the Bell’ (1821) and William Mudford’s ‘The Iron Shroud’ (1830), for example, can clearly be seen in ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’. The collection also contains an author’s preface in which Poe famously counters the common criticism that his work was of the ‘German’ school, that is outdated and rather vulgar gothic romance: ‘If in many of my productions terror has been the thesis,’ he wrote, ‘I maintain that terror is not of Germany but of the soul.’ This is in many ways the first manifesto of his art.

It has been suggested that by ‘Grotesque’ Poe meant ‘horror’ much as we use the term today to define the genre, that is a story with a focus on gory physical violence, whereas ‘Arabesque’ refers to much more metaphysical and psychological states of terror. Poe was certainly drawn to the gothic aesthetically, but he also knew that it sold. There is also certainly the influence of the eighteenth-century gothic romance in his fiction, the powerful evocations of gloom, decay and extravagance, as well as the surgical shock of the Regency Tales of Terror, but there are also recurring themes of isolation and destructive self-revelation, which place him more in the American gothic tradition, particularly the work of Charles Brockden Brown and Nathaniel Hawthorne. There is further an ambivalence of meaning that drives the external threat of the notionally supernatural to something much more psychological. For Poe’s heroes, terror invariably comes from within, with the true horror being the loss of self through pushing an imaginative quest, often for Beauty, sometimes revenge, so far past the conventional boundaries of human consciousness – into the ‘elevating excitement of the Soul’ – that it becomes indistinguishable from madness.

All of Poe’s most memorable characters withdraw from the world into heavily draped, candlelit rooms in which they cultivate their inner life to the point they lose touch with reality completely, developing, like Roderick Usher, a ‘morbid acuteness of the senses’ and almost mystical perception. When Hawthorne’s characters became so isolated, they lost their souls; Poe’s lost their minds, or their lives, or both. In ‘The Masque of the Red Death’, for example, Prince Prospero and his court take refuge from a plague in the exotic chambers of a battlemented abbey, where they cultivate Beauty in its most elaborate and artificial forms in an increasingly wild Bacchanal that makes the arrival of the fatal virus inevitable. This concept is perhaps most perfectly realised in ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, in which Usher’s synaesthesia allows him the Platonic perception of Beauty in its ideal form, but makes the ordinary trappings of real-life unbearable:

…the most insipid food was alone endurable; he could wear only garments of certain texture; the odours of all flowers were oppressive; his eyes were tortured by even a faint light; there were but peculiar sounds, and these from stringed instruments, which did not inspire him with horror.

There is a hint of incest, of inbreeding, as the family line, the ‘house’ comes to its end in Usher, tormented by a recessive gene, a ‘family evil’. But whether his acute sensitivity is a product of a diseased mind, or his growing insanity is the result of this extreme cultivation of the senses is not the point. Rather, these two states merge into a single image of terror in the gothic epiphany of Usher’s poem ‘The Haunted Palace’, which ends: ‘A hideous throng rush out forever/And laugh – but smile no more.’ The ‘Palace’ is Usher’s own mind, of course, and the attempt to find an ideal state of perception ends only in madness and despair, in that insane, mirthless laugh that closes the poem and is then heard in reality when Madeline Usher breaks out of her tomb and attacks her brother as the house collapses around them, just as Usher’s imagination has reached its own fatal climax. As in ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ and ‘The Oval Portrait’, it is as if art and beauty suck the life out of the seeker, the experience Thanatic and destructive rather than erotic and creative, which was certainly Poe’s experience of laying down his life for literature. In other stories, such as ‘The Cask of Amontillado’, ‘Berenice’, and ‘The Tell-tale Heart’, the disconnect comes in the rational voice of the murderer. The more meticulously they plan, the more ‘scientific’ their method, the crazier they become, while always that which appears supernatural, like the haunting of her husband by ‘Ligeia’, are merely reflections of imagination in decay, whether through grief and loss, passion, or opium addiction, often in a luxurious and languid decline which comes to a sudden stop in a shocking and fatal conclusion.

Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque was a critical success but not a financial one, and when Poe prosed a second edition including eight new tales to his publishers in 1841, they turned him down.

When the Philadelphia journalist and publishing entrepreneur George Rex Graham acquired Burton’s and merged it with another periodical, Atkinson’s Casket, in 1840, Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine was born. Poe became editor in February 1841 for a salary of $800 PA, abandoning plans to start his own magazine, The Penn. Graham promised to support Poe’s project at a later date, but he never did. Under Poe’s stewardship, Graham’s turned an annual profit of around $25,000. As both a savage but brilliant literary critic and an author, Poe wrote much of the work he is most widely remembered for at Graham’s, including ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ – widely regarded as the first modern detective story – ‘A Descent into the Maelström’, and ‘The Masque Of The Red Death’. He also wrote ‘The Gold Bug’ for Graham’s, but bought it back to enter into the Dollar Newspaper’s writing contest, which it won, significantly expanding Poe’s popular readership and netting $100 in prize money, by far the most he ever earned for a story.

For reasons that are again unclear, or largely apocryphal, Poe left Graham’s in April 1842, around the time his young wife began to show signs of the consumption that would ultimately kill her. He was replaced by the rival and equally acerbic literary critic and anthologist Rufus Wilmot Griswold. Griswold was paid $200 a year more than Poe and given more editorial autonomy by Graham. The view among the Philadelphia literati, however, was that the talent had left the building, the novelist George Lippard writing, ‘It was Mr Poe that made Graham’s Magazine what it was a year ago; it was his intellect that gave this now weak and flimsy periodical a tone of refinement and mental vigor.’ Although the two men had started out on reasonably cordial terms, Poe had irked Griswold with a lukewarm review of one of his books and Griswold had irked Poe by earning more at Graham’s. Matters were not helped the following year by Graham announcing his dissatisfaction with Griswold and trying (unsuccessfully) to entice Poe back. Both men were also rivals for the affection of the popular poet Frances Sargent Osgood, despite all three being married at the time. Although Poe continued to be an occasional contributor, there are stories that Griswold deliberately kept his work out of the magazine, and it is notable that when he offered ‘The Raven’ to Graham it was rejected.

‘The Raven’ subsequently saw print in the Evening Mirror in January 1845, published in New York, where the family, including Virginia’s mother, had moved the year before and now lived in a state of genteel poverty, Poe working for the Mirror as a literary critic. The poem, for which Poe was paid $9, was an immediate popular sensation. Poe was now a famous author and was able to supplement his pitiful writing income with lecturing. That year, he wrote his seminal ‘Philosophy of Composition’ (published in Graham’s), in which he argues fluently that ‘length’, ‘unity of effect’ and a ‘logical method’ are the cornerstones of good writing. Poe’s methodology (which he applies to ‘The Raven’) embraces aestheticism and rejects didacticism while acknowledging that the purest subject in art is death:

Melancholy is thus the most legitimate of all the poetical tones … I asked myself — ‘Of all melancholy topics, what, according to the universal understanding of mankind, is the most melancholy?’ Death — was the obvious reply. ‘And when,’ I said, ‘is this most melancholy of topics most poetical?’ From what I have already explained at some length, the answer, here also, is obvious — ‘When it most closely allies itself to Beauty: the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world — and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover.’

As Angela Carter once put it, Poe really did ‘like dead girls the best’, but then he lost every woman he really loved: first his mother, then his foster-mother, then his first love, and then his wife. That year he also supervised the Wiley & Putnam editions of his Tales and The Raven and Other Poems, started an unseemly critical war with Longfellow, and became editor and then proprietor of the Broadway Journal (which ceased publication the following year due to lack of investment). His work also broke through in France, leading to Baudelaire’s influential translations. Poe would later claim he had lived in France, but there is no evidence that aside from his period in Britain as a child, he ever left America. He liked to present himself as a Byronic wanderer, often to cover periods of unemployment and his time in the army.

The family moved to a small cottage in Fordham in the spring of the following year, about fourteen miles outside the city. Virginia was now clearly dying, and despite Poe’s literary celebrity, the couple remained in the same bleak state of poverty as before. This stark contrast between public fame and private suffering must have been terrible, and Poe began to drink after a long period of abstinence. Poe would later write of this period, of watching his wife rally and then fade: ‘I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity. During these fits of absolute unconsciousness, I drank – God only knows how often or how much. As a matter of course, my enemies referred the insanity to the drink, rather than the drink to the insanity.’ Virginia died on January 30, 1847, aged 25.

Although Poe remained creatively productive, continuing to lecture, write both fiction and literary criticism, and work on his ambitious ‘Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe’, Eureka, his behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic, as was his health. He was also desperate for female companionship; a strange quest – like many of his protagonists – for a transcendent, spiritual love with an idealised woman, but crossed with the desire for the stability of ordinary domestic life. Frances Osgood had by now reconciled with her husband, but Poe was soon courted by the rich and widowed Rhode Island poet Sarah Helen Whitman, their romance beginning in verse in national magazines before they physically met. Poe proposed and dreamed of establishing a literary dynasty, but her family strongly disapproved of him and the engagement was broken off, ostensibly due to his drinking. While this relationship was based on a meeting of intellects, Poe was at the same time drawn to the much more earthy widow, Nancy Lock ‘Annie’ Richmond, who offered warmth and security. He was still writing passionate love letters to Annie when a lecture tour took him back to Richmond and Sarah Elmira Royster, now the widowed Mrs Shelton. They became engaged (though he wrote to his mother-in-law that ‘I want to live near Annie’ as well), and Poe joined a temperance society. Richmond folk welcomed their famous son home with open arms, and on September 27, 1849, he left for New York to settle his affairs, planning to relocate to Richmond and marry Sarah. He never got there, and he never came back. Ten days later, he was dead.

From this point, the gothic legend spread… Poe was partly to blame in his own lifetime for telling tall autobiographical tales to cover a life of poverty, illness and failure. He was, he variously claimed, a seasoned traveller and adventurer – including extended trips to Greece and Russia – a great academic, an athlete, and the author of many works under assumed names. (He even claimed to have been the French novelist Eugène Sue.) On the day Poe was buried, an obituary appeared in the New York Tribune that began:

Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it. The poet was well known, personally or by reputation, in all this country; he had readers in England, and in several states of Continental Europe, but he had no friends.

This bizarre eulogy went on to paint a false picture of Poe the debauched lunatic, who ‘walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayers, (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned).’ The author of this garbage was Griswold, a man who could really bear a grudge. Somehow, he managed to become Poe’s literary executor, and set about trashing his rival’s posthumous reputation. Griswold claimed Poe had made him executor, but in reality, he’d conned Poe’s mother-in-law into signing over the rights. Griswold curated Poe’s Collected Works in 1850, which was a nice little earner, and gave the anthologist literary status by editorial association. To this he contributed a ‘Memoir of the Author’, again depicting Poe as a depraved, drunken, opium-fuelled madman, through a series of entirely fictitious anecdotes, very selectively quoting Poe’s correspondence as evidence, often altering them or outright forging. Poe’s friends, led by John Neal, attacked Griswold in the press as a publicity-seeking charlatan, but the damage was done. Poe himself had already laid so many false trails that it was hard to get to the bottom of him, and his death was as mysterious as much of his life. Griswold’s book, meanwhile, was widely reprinted, quickly becoming the standard biographical source on Poe. Readers also perpetuated the myth, and often still do, associating Poe with his own protagonists, ascribing biographical and psychological interpretations to the stories, and thrilled with the idea of reading transgressive texts by an ‘evil’ and ‘immoral’ sinner. Dr Moran, meanwhile, dined out on Poe’s last moments for decades, each telling wackier than the last, while Dr Snodgrass used his ignominious demise as the subject of a series of temperance lectures.

Even though Poe was known to love a good practical joke, one wonders if a writer who believed so strongly in the determined separation of life and art would be impressed at his position in modern Americana, despite his parallel literary status in the academy. Maybe he’d enjoy being a Goth icon, his face tattooed on many a dark, pale cadaverous beauty, lines of his poetry engraved on heavy Alchemy jewellery…

One thing is certain. Like all visionaries, Poe was ahead of his time. His sense of the artist as a detached craftsman and his attempt at a kind of ontological unified field theory of science, art and spirituality in Eureka in many ways foreshadowed literary Modernism – eschewing, as he did, the Romantic’s view of the poet as the prophet or moral arbiter – as much as he influenced the Symbolists and Decadents, crime and science fiction writers and, most of all, modern American Horror. From H.P. Lovecraft to Richard Matheson, Robert Bloch, EC Horror Comics, Stephen King, George A. Romero, and beyond, the twentieth-century genre owes a huge debt to Poe, as does the art of the short story itself. As a man who collected Classical knowledge to recycle in his journalism, if presented with this monolithic hyper-real representation of his short and miserable life, he may well have quoted Marcus Valerius Martial with a sardonic smile: ‘If fame is to come only after death, I am in no hurry for it.’

Stephen Carver

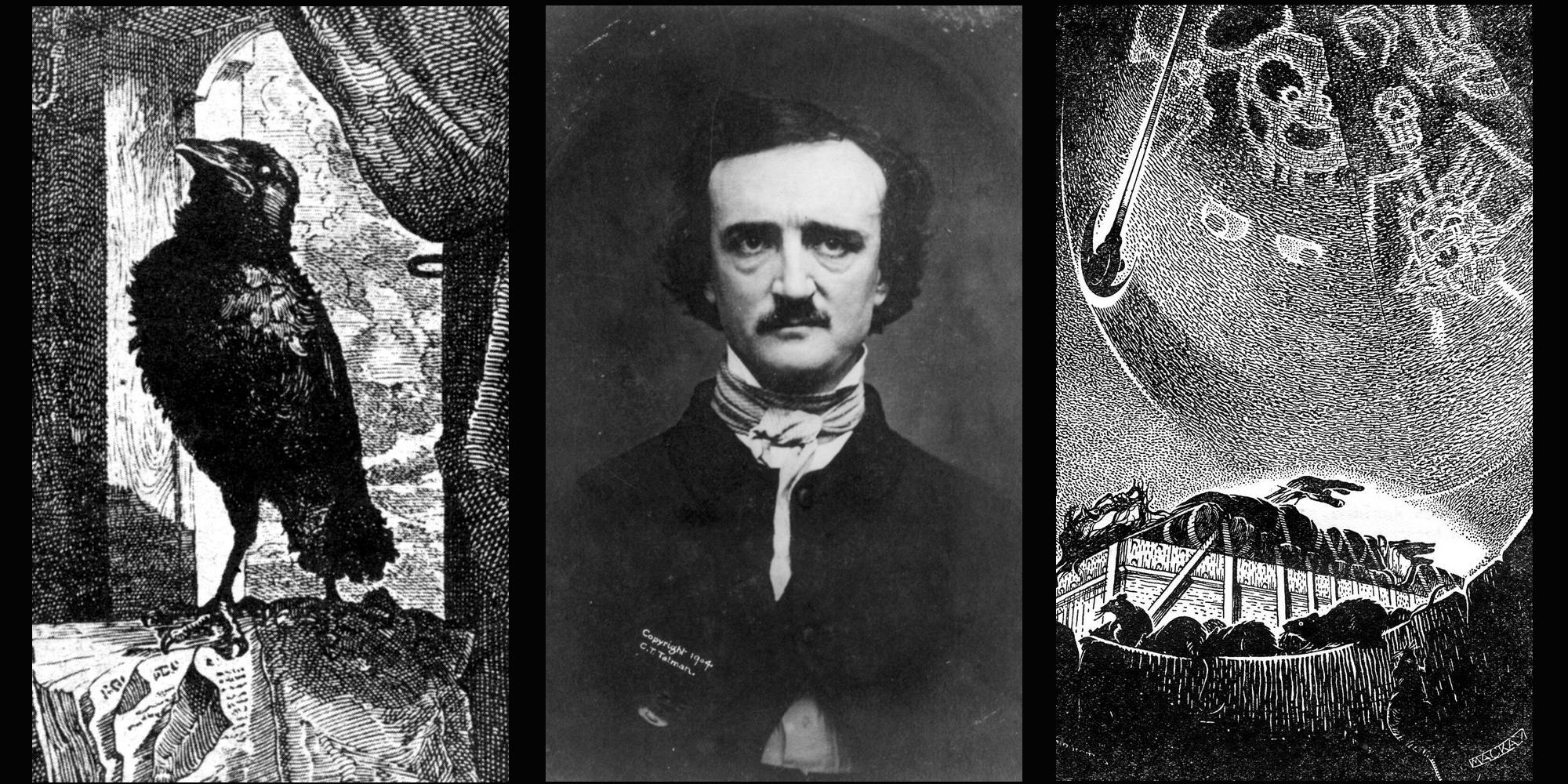

Images: Edgar Allan Poe with illustrations from The Raven and ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’. Alamy Stock Photos

Books associated with this article