J.S. Le Fanu and the Golden Age of the Ghost Story

Stephen Carver looks at the work of the influential Irish author.

As the nights grow longer and colder and we move inexorably towards Halloween, the readerly mind turns naturally towards the ghost story. And while pumpkins are carved and displayed as an invitation to trick-or-treaters, let us not forget that their original purpose was to ward off the evil spirits that walk on All Saint’s Eve, the same night as the ancient Gaelic festival of Samhain. Originally carved from turnips, the tradition of the Halloween Jack O’Lantern began in Ireland as a symbolic representation of a soul in purgatory. According to Irish folklore, the original ‘Jack’ met the Devil on the way home from a night’s drinking and trapped him up a tree by cutting the sign of the cross into the bark. Before releasing him, Jack strikes a bargain that the Devil will never claim his soul. After a life of debauchery, Jack’s soul is barred from Heaven, but Hell won’t take him either. To make him go away, Satan hurls a burning coal like a publican discouraging a stray dog. Freezing, Jack places the coal in a hastily hollowed-out turnip and fashions a lamp. His lost soul has been wandering Ireland ever since carrying his lantern – lit by the eternal fire of Hell – and looking for a resting place. (The pumpkin was adopted by Irish immigrants to America, being more physically impressive and a lot easier to carve than a turnip.) According to Irish mythology, during Samhain the door to what the Celts called the ‘Otherworld’ swung open, letting supernatural beings and the souls of the dead into the world of men. While ‘Bealtaine’ (May Day) was a summer festival for the living, Samhain was a festival for the dead. It is thus in every way appropriate that the father of the modern ghost story, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, was an Irishman…

If you’ve not read Le Fanu yet, chances are you’ve come across one of the film or television adaptations, especially if you’re of my generation and therefore cut your gothic teeth on Hammer Films and the BBC’s Ghost Stories for Christmas in the 1970s. I got into Le Fanu as a kid having been traumatised by the BBC dramatization of Schalcken the Painter. The vision of the young artist’s first love, Rose, cavorting with the ‘livid and demoniac form of Vanderhausen’ in the catacombs beneath Rotterdam gave me nightmares for weeks. I, of course, immediately searched out the original story, and picked up a second-hand anthology with Peter Cushing on the cover published to promote The Vampire Lovers, the Hammer version of Le Fanu’s vampire story, Carmilla. I was still using this copy at university, which raised a few eyebrows, I can tell you, and Hammer went on to produce their ‘Karnstein Trilogy’, following The Vampire Lovers with Lust for a Vampire and Twins of Evil. Not that these were the first Le Fanu movies; there is also the haunting German Expressionist Vampyr (1932), directed by Carl Dreyer. Who’d have thought lesbian vampires would have had such enduring appeal?

The descendant of a noble Huguenot family, Dubliner J.S. Le Fanu (1814–1873) was in his own time a bestselling author. He was known for his historical, mystery, and sensation fiction (he is credited with inventing the ‘locked-room mystery’ with his story ‘A Passage in the Secret History of an Irish Countess’ published in 1838, three years before Poe’s ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’), and above all horror. Described by his friend Alfred Perceval Graves – the father of Robert – as ‘one of the greatest masters of the weird and the terrible’, after his early death at the age of 58, Le Fanu’s reputation was crowded out of Victorian literature by his contemporaries, Dickens, Thackeray, Wilkie Collins, and the Brontës; all of whom he in some form influenced and whose sales he frequently rivalled.

Although called to the bar, Le Fanu chose instead to devote himself to writing, following in the footsteps of his great-uncle, the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, a precarious profession he later described in his novel All in the Dark:

Literary work, the ambition of so many, not a wise one perhaps for those who have any other path before them, but to which men will devote themselves, as to a perverse marriage, contrary to other men’s warnings, and even to their own legible experiences of life in a dream.

He began contributing articles, ballads, and short stories to the Dublin University Magazine in 1838 including his first supernatural tale, ‘The Ghost and the Bone-Setter’, which is played for laughs, and the chilling ‘Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter’, which isn’t. From 1840, he began acquiring financial interests in several Irish newspapers. Le Fanu had been fascinated by folklore and superstition since his childhood, the Irish journalist Samuel Carter Hall wrote of him:

I knew the brother’s Joseph and William Le Fanu when they were youths at Castle Connell, on the Shannon … They were my guides throughout the beautiful district, and I found them full of anecdote and rich in antiquarian lore, with thorough knowledge of Irish peculiarities.

William became a civil engineer, and Joseph never gave up on those ‘Irish peculiarities’, becoming, in the words of E.F. Benson, one of his twentieth-century disciples, an ‘unrivalled flesh-creeper’ whose ‘tentacles of terror are applied so softly that the reader hardly notices them till they are sucking the courage from his blood.’

Prior to his marriage to Susanna Bennett in 1843, Le Fanu wrote prolifically for the Irish magazine market, producing a series of gothic, historical and humorous short stories for the Dublin University Magazine later collected as The Purcell Papers. These were written under the framing umbrella of being ‘extracts’ from the ‘MS. Papers of the late Rev. Francis Purcell, of Drumcoolagh’, a fictitious Catholic priest, were posthumously collected and edited by an unidentified friend, adding both a sense of authenticity and gothic ambiguity to the narratives. These include the story ‘A Chapter in the History of a Tyrone Family’ (1839) which shares significant similarities of the plot – aristocratic bigamy and the ‘madwoman in the attic’ – with Jane Eyre (1847). The best of the rest of Le Fanu’s early ghost stories were anthologised by M.R. James in Madam Crowl’s Ghost and Other Stories in 1923, marking the beginning of a revival of interest in Le Fanu’s supernatural fiction. James’ introduction is expansive, declaring that Le Fanu ‘stands absolutely in the first rank as a writer of ghost stories’, continuing ‘Nobody sets the scene better than he, nobody touches in the effective detail more deftly.’ James chooses twelve tales that are representative of Le Fanu’s art, including haunted houses (‘An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street’); Faustian pacts (‘Sir Dominick’s Bargain’); Irish legends (‘The Child that went with the Fairies’); warnings from Hell (‘The Vision of Tom Chuff’); bitterly contested inheritances (‘Squire Toby’s Will’); portents of doom (‘The White Cat of Drumgunniol’); historical curses (‘Ultor de Lacy’); and terrible, long concealed crimes (‘Madam Crowl’s Ghost’). The dying caste of the Protestant Anglo-Irish – like Le Fanu’s own family line – is a recurring motif, as is the similar decline of the Catholic aristocracy, symbolised by the ruined castles that dot Le Fanu’s textual landscape. There is also a dark sense of humour running through these tales, which sets Le Fanu’s style apart from his contemporary, Edgar Allan Poe. Like James’ own stories, these are presented as first-hand accounts of events occurring in living memory, usually related to, or collected by a gentleman scholar or antiquarian. Elegantly structured, the stories follow James’ prescription for the perfect ghost story:

Two ingredients most valuable in the concocting of a ghost story are, to me, the atmosphere and the nicely managed crescendo … Let us, then, be introduced to the actors in a placid way; let us see them going about their ordinary business, undisturbed by forebodings, pleased with their surroundings; and into this calm environment let the ominous thing put out its head, unobtrusively at first, and then more insistently, until it holds the stage.

James notes that these tales are now ‘forgotten’ and were frequently published anonymously. He, therefore, concludes with the appeal that, ‘I shall be very grateful to anyone who will notify me of any that he is fortunate enough to find.’ In comparing the style and tone of James’ famous Edwardian ghost stories with those of Le Fanu, it is clear how much of a debt was owed.

After a promising start, Le Fanu largely abandoned fiction in favour of political journalism and a growing family (Susannah bore him three daughters and a son), although he did write two minor historical novels in the manner of Walter Scott and Harrison Ainsworth, The Cock and Anchor (1845) and Torlogh O’Brien (1847) and publish the collection Ghost Stories and Tales of Mystery (1851). By birth and inclination a Conservative, Le Fanu broke ranks and supported Nationalist politicians John Mitchel and Thomas Francis Meagher in lobbying the indifferent British government to intervene during the Great Famine. As a newspaper proprietor, he was courted as an advocate by William Smith O’Brien, and it was through these connections that he found himself inadvertently on the fringes of the failed 1848 ‘Famine Rebellion’ which saw Mitchel, Meagher and O’Brien transported for sedition. This cost Le Fanu his nomination to be Tory MP for County Carlow, effectively ending his political ambitions and leaving him, like many other Irishmen, caught between the opposing forces of Protestant Ascendancy and Catholic Nationalism. This tension, subtly allegorised, can be felt in much of his later writing in an ambivalent stance towards religion, while the destructive recurrence of history in the present is a key motif, as it is in Northern Ireland to this day.

These tensions were also present in Le Fanu’s domestic life. His father-in-law, George Bennett QC, the son of the even more formidable Tory MP Judge John Bennett, was a bastion of the Anglo-Irish gentry and unimpressed with his son-in-law’s indirect flirtation with the ‘Young Irelanders’. This put Susannah, already a nervous woman, between husband and father and undoubtedly contributed to her growing anxiety and depression. This was compounded when Le Fanu ceased to attend church due to his increasing interest in the writings of the Swedish philosopher and Christian mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772). Susannah’s fragile mental state was made worse by the unexpected death of her father in 1856. From then on, she became increasingly neurotic, Le Fanu recording in his diary that:

If she took leave of anyone who was dear to her she was always overpowered with an agonizing frustration that she could never see them again. If anyone she loved was ill, though not dangerously, she despaired of their recovery.

The crisis came to a head when Susannah had a vision of her dead father:

She one night thought she saw the curtains of her bed at the side next the door drawn, & the darling old man, dressed in his usual morning suit, holding it aside, stood close to her looking ten or (I think) twelve years younger than when he died, & with his delightful smile of fondness & affection beaming upon her [he said] ‘There is room in the vault for you, my little Sue.’

(Twelve years earlier was when Susannah married Le Fanu, from which she presumably dated the breach with her father.) Not long after, in April 1858, she died suddenly from a ‘hysterical attack’ aged only thirty-four. The grief-stricken Le Fanu stopped writing entirely for the next three years.

It was another death, this time that of his mother in 1861, that triggered the next, most significant, and final stage in Le Fanu’s literary career. That year, he bought the Dublin University Magazine for £850 and became both its editor and principal contributor. A period of intense productivity followed as Le Fanu vanished from Dublin society so completely that his friends dubbed him the ‘Invisible Prince’, Graves later recalling that:

He was for long almost invisible, except to his family and most familiar friends, unless at odd hours of the evening, when he might occasionally be seen stealing, like the ghost of his former self, between his newspaper office and his home in Merrion Square; sometimes, too, he was to be encountered in an old out-of-the-way bookshop poring over some rare black letter Astrology or Demonology. To one of these old bookshops, he was at one time a pretty frequent visitor, and the bookseller relates how he used to come in and ask with his peculiarly pleasant voice and smile, ‘Any more ghost stories for me, Mr.—?’ and how, on a fresh one being handed to him, he would seldom leave the shop until he had looked it through.

There followed an uninterrupted run of serial novels, commencing with the eclectic historical mystery The House by the Churchyard (1863, later a key point of reference in James Joyce’s even madder Finnegans Wake). This was followed by Wylder’s Hand and Uncle Silas (1864); Guy Deverell (1865); All in the Dark (1866); The Tenants of Malory (1867); A Lost Name and Haunted Lives (1868); The Wyvern Mystery (1869); Checkmate and The Rose and the Key (1871); and Willing to Die (1872). The majority of these novels reflected the current popular trend for Sensation Fiction (with the exception of All in the Dark, which was a satire on Spiritualism), and the author with which Le Fanu was most often compared was Wilkie Collins.

Le Fanu’s son, Brinsley, later described his father’s writing process to the literary historian Stewart Marsh Ellis:

He wrote mostly in bed at night, using copy-books for his manuscript. He always had two candles by his side on a small table; one of these dimly glimmering tapers would be left burning while he took a brief sleep. Then, when he awoke about 2 a.m. amid the darkling shadows of the heavy furnishings and hangings of his old-fashioned room, he would brew himself some strong tea – which he drank copiously and frequently throughout the day – and write for a couple of hours in that eerie period of the night when human vitality is at its lowest ebb and the Powers of Darkness rampant and terrifying.

As the Rev. Jennings, the haunted protagonist of ‘Green Tea’ proclaims, ‘I believe that everyone who sets about writing in earnest does his work, as a friend of mine phrased it, on something—tea, or coffee, or tobacco.’ Brinsley believed the excessive caffeine intake contributed to the nightmares that plagued his father, and that these bad dreams were the source of many a story. It is difficult to read this anecdote and not think of the malevolent black monkey of ‘Green Tea’, glaring, blaspheming, and shaking his tiny fists at the doomed Jennings.

Several of these novels were expanded rewrites of earlier stories. His best-known novel, the gothic mystery Uncle Silas, started life as ‘Passage in the Secret History of an Irish Countess’ via ‘The Murdered Cousin’ from Ghost Stories and Tales of Mystery. A Lost Name was based on ‘The Evil Guest’ (also from the Ghost Stories), which in turn was a revision of the early story ‘Some Account of the Latter Days of the Hon. Richard Marston of Dunoran’. ‘A Chapter in the History of a Tyrone Family’ became The Wyvern Mystery. It is as if the early short fiction served as roadmaps for the novels, ways in which Le Fanu could explore and interrogate the themes that clearly haunted him: his Swedenborgian views on the afterlife, the destructive cycle of family history, that which is hidden (locked rooms are a recurring device), doppelgängers, and the decline of the Irish aristocracy. He also contributed to All the Year Round, and was greatly admired by Dickens, who sought his advice on ‘spectral illusions’ when writing his seminal ghost story ‘The Signalman’ (1866). In addition to these novels, Le Fanu also compiled his remarkable collection of supernatural stories In A Glass Darkly (1872), comprising the stories ‘Green Tea’ (first published in All the Year Round), ‘The Familiar’ (originally ‘The Watcher’ from the 1851 Ghost Stories), ‘Mr. Justice Harbottle’ (a prequel to ‘An Account of Some Strange Disturbances in Aungier Street’ in which the story of the hanging ghost is told), ‘The Room in the Dragon Volant’ (a tale of drug-induced catalepsy and premature burial that would give Poe a run for his money), and the novella Carmilla, a forerunner of Dracula. He was planning the novel The House of Bondage – a reworking of his short story ‘The Mysterious Lodger’ – when he died, quite suddenly, in his sleep on February 7, 1873, probably from a heart attack. Dublin legend has it that he had been plagued by a recurring nightmare of a derelict house he feared would bury him and that when his body was found, the attending doctor looked into his dead, horrified eyes – like a character from one of his stories – and declared, ‘So the house has fallen at last.’ His children always disputed this, claiming the look on his face was serene.

It was M.R. James’ recommendation that all those coming to Le Fanu for the first time should begin with In A Glass Darkly, ‘where they will find the very best of his shorter stories.’ This is very good advice. In A Glass Darkly is for scholars of the Victorian gothic the definitive collection of nineteenth-century ghost stories, the zenith of the so-called ‘Golden Age of the Ghost Story’, the period roughly between the last of the original gothic romances and the decline of Spiritualism before the Great War when supernatural fiction became so ubiquitous that it descended into cliché (much as it has again today through the industrial output of television streaming services): the era of Poe, Dickens, G.W.M. Reynolds, Charlotte ‘J.H.’ Riddell, Amelia B. Edwards, Robert Louis Stevenson, Edith Wharton, Kipling, and, of course, Le Fanu.

‘In A Glass Darkly’ paraphrases the King James version of 1 Corinthians 13:12: ‘For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.’ The original passage refers to our necessarily partial knowledge of God, which St. Paul likens to a reflection in a dim or tarnished mirror, before the coming of Christ will allow us to know God and his ways as he knows us now in full revelation. Le Fanu, however, is giving this a much more Swedenborgian spin, as explained by the collection’s framing narrator (framed, himself, by another editor like Father Purcell before him), the occult detective Dr. Martin Hesselius, an ancestor of Stoker’s Professor Van Helsing and William Hope Hodgson’s Thomas Carnacki, the ‘Ghost-Finder’:

Of those whose senses are alleged to be subject to supernatural impressions—some are simply visionaries and propagate the illusions of which they complain, from diseased brain or nerves. Others are, unquestionably, infested by, as we term them, spiritual agencies, exterior to themselves. Others, again, owe their sufferings to a mixed condition. The interior sense, it is true, is opened; but it has been and continues open by the action of disease.

This is pure Swedenborg, as cited by the unfortunate Rev. Jennings in ‘Green Tea’: ‘When man’s interior sight is opened, which is that of his spirit, then there appear the things of another life, which cannot possibly be made visible to the bodily sight.’

The essence of Swedenborg’s mystical theology, outlined in his Arcana Cœlestia (Heavenly Mysteries or Secrets of Heaven, 1749) is his ‘correspondence theory’ that there is a relationship among the natural (‘physical’), the spiritual, and the divine worlds. Swedenborg claimed to be able to see these other worlds as clearly as his own as a result of a divine revelation and related these other planes of existence directly to his interpretation of the bible. (Victor Hugo suggests in passing in Les Misérables that Swedenborg, once a respected Enlightenment scientist, had ‘glided into insanity’.) Le Fanu, however, appreciated the more gothic possibilities of the correspondence theory, as later noted by W.B. Yeats in Explorations:

It was indeed Swedenborg who affirmed for the modern world, as against the abstract reasoning of the learned, the doctrine and practice of the desolate places, of shepherds and midwives and discovered a world of spirits where there was scenery like that of earth, human forms, grotesque or beautiful, senses that knew pleasure and pain, marriage and war, all that could be painted on canvas, or put into stories to make one’s hair stand up.

This ‘opening of the interior sense’, as Hesselius calls it, means that some hapless individuals – the subjects of his case studies, who he never saves – are alert to the inhabitants of these other planes, which appear as apparitions, demons, or hallucinations, depending upon the official explanation. (Doctors in Le Fanu are always wrong, and priests aren’t much more reliable.) This is similarly true for the protagonist of ‘The Familiar’, Captain Barton, who is, like Jennings, stalked by something terrible:

The fact is, whatever may be my uncertainty as to the authenticity of what we are taught to call revelation, of one fact I am deeply and horribly convinced, that there does exist beyond this a spiritual world—a system whose workings are generally in mercy hidden from us—a system which may be, and which is sometimes, partially and terribly revealed.

The implication is clear: When we can see them, they can see us.

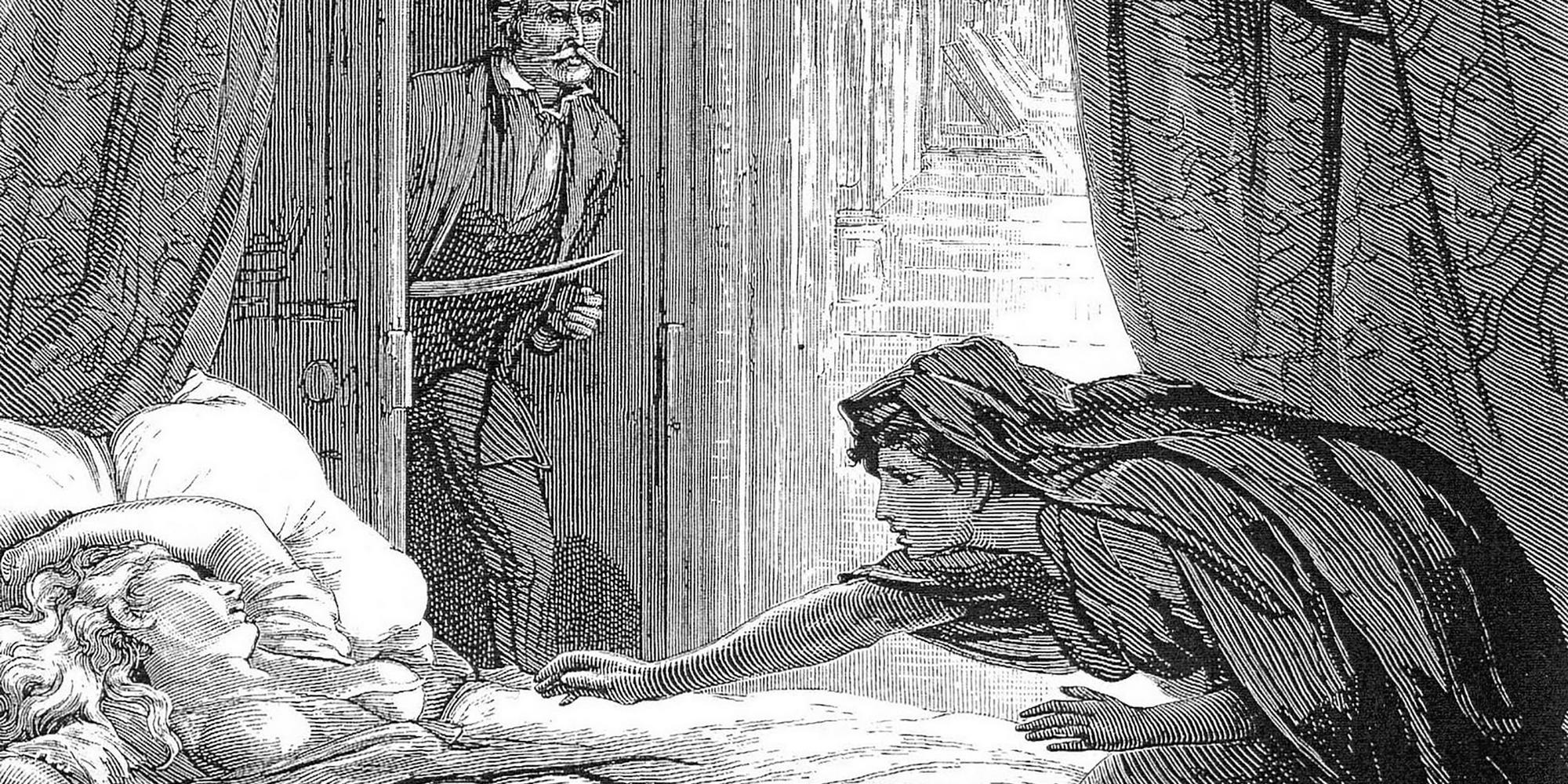

Hesselius’ strangest case, and probably his most culturally influential (though ‘Green Tea’ is very popular with horror anthologists), is that of Carmilla. It was, he wrote, ‘involving, not improbably, some of the profound arcana of our dual existence, and its intermediates.’ Originally published as a serial in the London magazine The Dark Blue, the story is narrated by an elderly woman from Styria in Austria, ‘Laura’, recalling the summer in her teens when a mysterious young woman, ‘Carmilla’, a homeless and itinerant noblewoman, came to stay at the family castle. Laura is lonely and Carmilla is the perfect companion, being charming, affectionate, and beautiful. The two also share an affinity having each, apparently, dreamed of the other as children, and Carmilla’s designs on Laura seem to go beyond mere friendship:

Sometimes after an hour of apathy, my strange and beautiful companion would take my hand and hold it with a fond pressure, renewed again and again; blushing softly, gazing in my face with languid and burning eyes, and breathing so fast that her dress rose and fell with the tumultuous respiration. It was like the ardour of a lover; it embarrassed me; it was hateful and yet over-powering; and with gloating eyes, she drew me to her, and her hot lips travelled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, ‘You are mine, you shall be mine, you and I are one forever.’ Then she had thrown herself back in her chair, with her small hands over her eyes, leaving me trembling.

Young women in the nearby village, meanwhile, are dying of a mysterious illness while Laura dreams at night of being visited by an enormous black cat…

Aristocratic vampires were not new in 1872. That distinction goes to Byron’s physician Dr. John Polidori, whose 1819 short story ‘The Vampyre’ introduced the Dracula-like (and Byronic) ‘Lord Ruthven’. There had also been the penny dreadful Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood (1845–47) by James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest (the creators of Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street). That said, the similarities between Carmilla and fellow Irishman Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) are striking. The name of Dracula’s insane familiar, ‘R.M. Renfield’, echoes Bertha Rheinfeldt, a friend of Laura’s family and another of Carmilla’s victims. Both stories have elaborate framing narratives and feature sexually magnetic antagonists posing as descendants of themselves; Carmilla and Count Dracula target female heroines, and both can transform into animals and pass through locked windows and doors. (Stoker’s Lucy Westenra is also both a Laura and Carmilla figure, being first human prey then undead predator.) Le Fanu’s ‘Baron Vordenburg’ is a similar expert to Van Helsing, and their method of killing vampires is essentially the same, as are the described symptoms of vampirism. The original opening chapter of Dracula, cut from the final draft and published separately as the short story ‘Dracula’s Guest’, features the female vampire Countess Dolingen von Gratz, and is also set in Styria. Fans of Stoker tend to play down the parallels, but why not read Carmilla and see for yourself? After all, as Picasso famously said, ‘Good artists copy, great artists steal.’

Had Le Fanu lived longer, he would probably have entered the Victorian gothic pantheon alongside Stoker and Stevenson. But for our purposes, part of the fun of Halloween is finding something scary that we don’t already know by heart, and, as M.R. James himself conceded, ‘I do not think that there are better ghost stories anywhere than the best of Le Fanu’s.’ So, this All Hallow’s Eve, settle back with Madam Crowl’s Ghost or In A Glass Darkly, preferably in the dead of night and, even better, in a solitary chamber, and when the house creaks suddenly, a branch brushes the window, or door swings slowly open by itself, it will be, as Le Fanu advised, ‘a pleasing terror’ that will thrill you.

Image: Engraving from Le Fanu’s 1872 Carmilla Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

In a Glass Darkly

Sheridan Le Fanu