Gore by Proxy: The Penny Dreadfuls. Part One

David Stuart Davies’ tells the story of the ‘Penny Dreadfuls’.

Part One: ‘More Blood’

We all like a good shiver and shake: to be thrilled at a distance by a chilling tale. Fictional horrors are fun. Even the most sedate of us enjoy vicariously something threatening and unpleasant while in the comfort and safety of our own armchair. That’s why horror films and murder mysteries are such big business today. It is a strange part of the human psyche that perfectly respectable folk who would not think of uttering that proverbial boo to a goose find enjoyment in such entertainments. However, it is nothing new and certainly our Victorian ancestors might well observe that the material that we see and read today is tame fare compared to the bloody literature churned out for their divertissement nearly two hundred years ago.

Britain in the nineteenth century experienced social changes that resulted in increased literacy amongst the working class. The rise of industrialisation helped to bring about secure employment for a large number of the population and so there was more money available to spend on entertainment. This in turn contributed to the growing popularity of the novel. Reading became the new leisure. As a result, there emerged a market for cheap popular literature, and the ability, thanks to the rise of the railway, for it to be circulated on a large scale to all parts of the country.

The first penny serials were published in the 1830s to meet this demand. These were priced to be affordable to working-class readers and were considerably cheaper than the serialised novels of authors such as Charles Dickens, which cost a shilling per part.

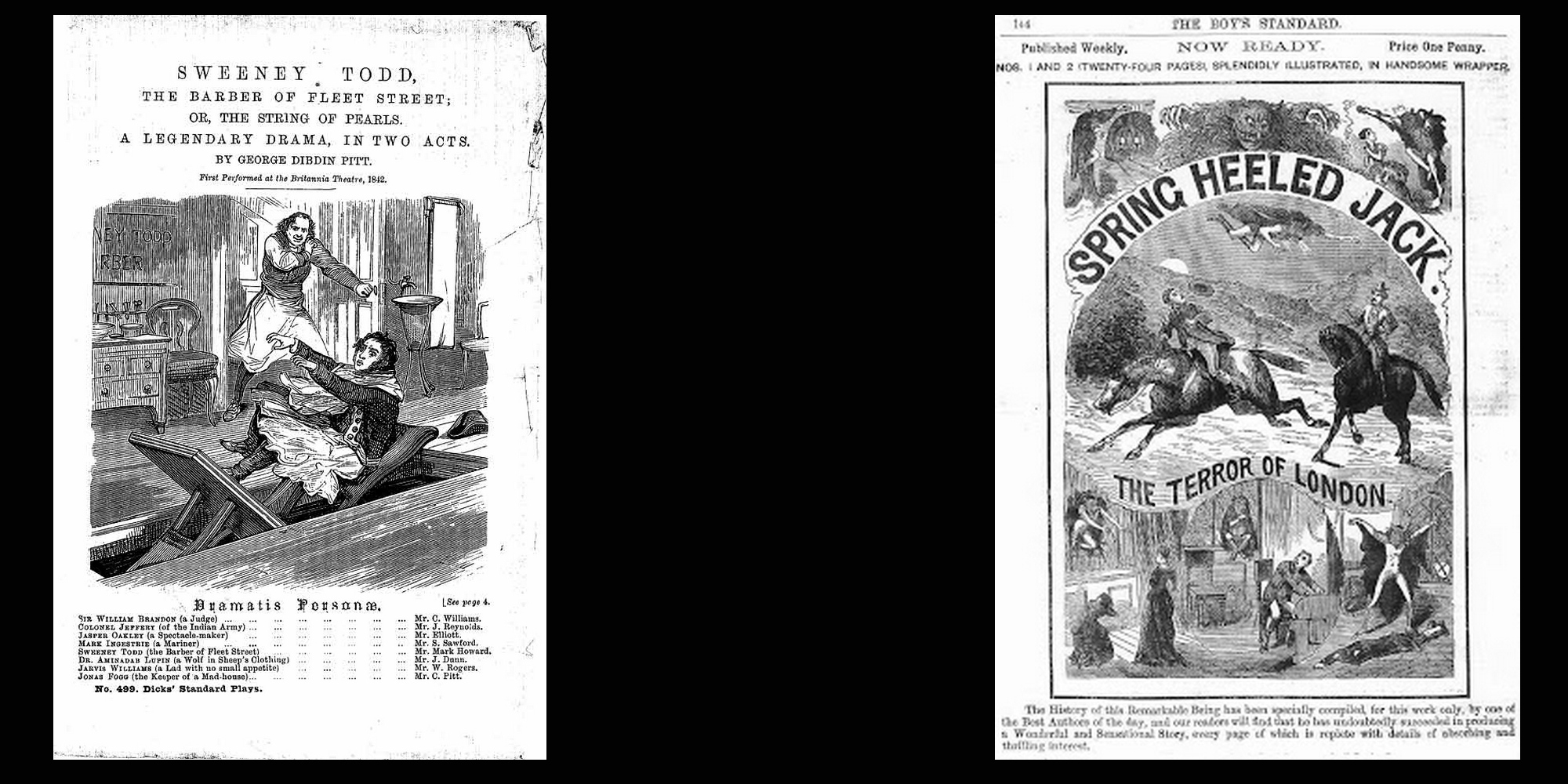

Penny bloods was the original name for the booklets that, in the 1860s, were renamed penny dreadfuls and told stories of rousing adventures, initially featuring pirates and highwaymen, but later concentrating on crime and detection. Issued weekly, each number, or episode, was eight (occasionally sixteen) pages, with a black-and-white illustration on the top half of the front page. Double columns of text filled the rest, breaking off at the bottom of the final page, even if it was the middle of a sentence.

The bloods were astonishingly successful, creating a vast new readership. Between 1830 and 1850 there were up to a hundred publishers of penny fiction, as well as the many magazines which now wholeheartedly embraced the genre. At first, the bloods copied popular cheap fiction’s love of late 18th-century gothic tales, the more sensational the better. They presented a dark view, one writer observed, of, ‘a world of dormant peerages, of murderous baronets, and ladies of title addicted to the study of toxicology, of gipsies and brigand-chiefs, men with masks and women with daggers, of stolen children, withered hags, heartless gamesters, nefarious roués, foreign princesses.’ A grotesque gallery indeed.

The first ever penny blood, in 1836, was Lives of the Most Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads, &c., in sixty parts. Highwaymen featured greatly in these periodicals. Gentleman Jack, a convoluted tale of one such individual, was published over four years, without too much worry about historical accuracy or continuity. One character was killed and then remarkably returned from the dead without explanation only to be killed again. Dick Turpin was a great favourite. His story, and especially the time he (supposedly) rode the 200 miles from London to York overnight, was retold endlessly. One version Black Bess; or, The Knight of the Road, continued for 254 episodes and Turpin was not executed until page 2,207.

Other serials were thinly-disguised plagiarisms of popular contemporary literature. The publisher Edward Lloyd, for instance, published a number of penny serials derived from the works of Dickens entitled Oliver Twiss, Nickelas Nicklebery, and Martin Guzzlewitt.

The illustrations were an essential element, as much an advertising tool as art. One regular reader said, ‘You sees an engraving of a man hung up, burning over a fire, and some…go mad if they couldn’t learn what he’d been doing, who he was, and all about him.’ It is not surprising, therefore, that one publisher’s standing instruction to his illustrators was, ‘more blood – much more blood!’

Indeed, the semi-literate – who made up an important part of their market – were reeled in by the lurid woodcuts: Black Bess, rearing against the moon; the heroine, bare-breasted and manacled in a burning attic; a bloodsucking fiend clambering over a four-poster bed.

The stories themselves were sometimes rewrites of gothic thrillers such as The Monk or The Castle of Otranto, as well as new stories about infamous criminals. Some of the most successful of these penny part stories were featured in The String of Pearls: A Romance which, in 1846, introduced Sweeney Todd, the ‘Demon Barber’ of Fleet Street who killed his clients for his neighbour Mrs Lovett to bake into meat pies. Even before it reached its conclusion, the story was adapted for the stage, setting the murderous barber on the road to world fame.

The authors of these labyrinthine tales, who might keep ten yarns spinning simultaneously, were paid at the rate of a penny a line, which had a visible effect on the text. Skilled practitioners knew that staccato sentences were the most profitable, and learned how to oblige the compositor to leave one or two words hanging at the end of a paragraph.

Probably the most successful penny blood was Mysteries of London, which first appeared in 1844. Written by G W M Reynolds, initially, it was based on a French serial, The Mysteries of Paris, but it soon took on a life of its own, spanning twelve years, 624 numbers and nearly 4.5 million words. Instead of highwaymen, this series was much closer to its readers’ own lives, contrasting the dreadful world of the slums with the decadent life of the careless rich.

Books associated with this article

The Monk

Matthew Lewis