Gore by Proxy: The Penny Dreadfuls. Part Two

The final part of David Stuart Davies’ story of the rise and fall of the ‘Penny Dreadful’.

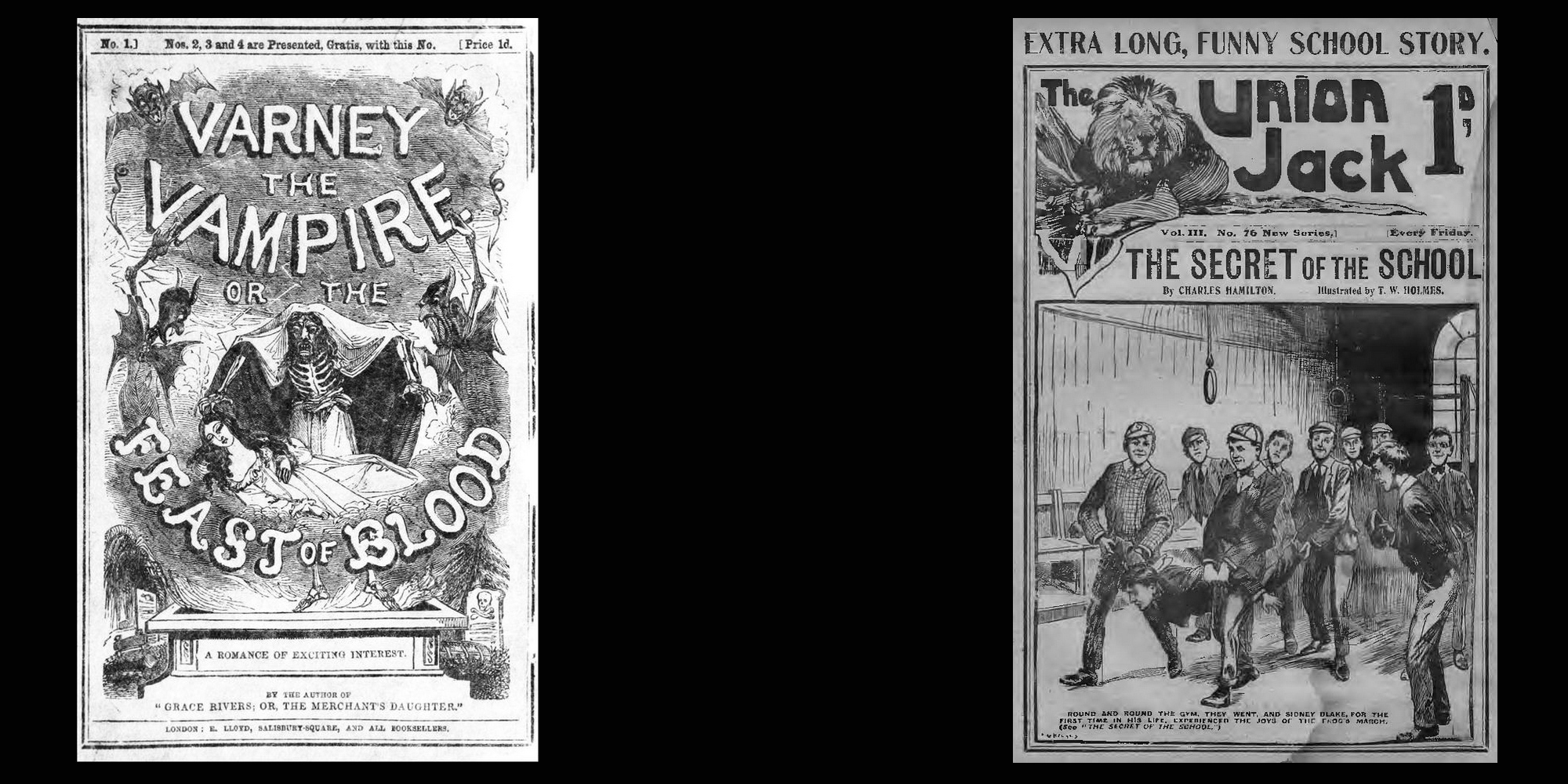

Varney & Co

One of the most successful and influential of all the penny dreadfuls was Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood by James Malcolm Rymer. It was first serialised in 1845–47 and was later published in book form. It is of epic length: the original edition ran to 876 double-columned pages divided into an exhausting 220 chapters. The saga totals nearly 667,000 words. It is the tale of the vampire Sir Francis Varney. The plot is at times inconsistent and confusing as if the author did not know whether to make Varney a literal vampire or simply a human who acts like one. He is portrayed as loathing his condition and is presented as a helpless victim of circumstances. He tries to save himself but is unable to do so. This is the first example of the sympathetic vampire, one who despises his bloodlust but is nonetheless a slave to it. He ultimately commits suicide by throwing himself into Mount Vesuvius, after having left a written account of his origin with an understanding priest. According to Varney, he was cursed with vampirism after he had betrayed a royalist to Oliver Cromwell and accidentally killed his own son afterwards in a fit of anger.

Varney was a major influence on later vampire fiction, most notably Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker. Many of today’s standard vampire trappings originated in the story: Varney has fangs, leaves two puncture wounds on the necks of his victims, has hypnotic powers, and has superhuman strength. However, unlike later fictional vampires, he is able to go about in daylight and has no particular fear of either crosses or garlic. He can eat and drink in human fashion as a form of disguise, although it is clear that the digestion of food and drink is a painful process to him. Varney’s vampirism seems to be a compulsive fit that comes upon him when his vital energy begins to run low; he appears as a regular, normally functioning person between feedings. In the TV series Penny Dreadful (2014), Dr. Van Helsing gives a copy of Varney the Vampire to Victor Frankenstein, stating that the story is more true than fiction.

Several authors who later published more respectable popular fiction began their careers writing penny bloods, including the journalist G. A. Sala, a protégé of Dickens, and Mary Elizabeth Braddon, later the author of the bestselling Lady Audley’s Secret, who began as the (pseudonymous) author of The Black Band, or, The Mysteries of Midnight, complete with a female killer who organises a European-wide network of criminals. As Mrs Braddon, herself observed, ‘the amount of crime, treachery, murder and slow poisoning, & general infamy required [by my readers]…is something terrible’. Yet it was precisely these ingredients that led the way to the ‘sensation’ novel. For example, Mrs Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White picked up on the high melodrama of the penny dreadful scenarios, but instead of highwaymen, pirates, or gothic dungeons, tucked them all neatly away under a tidy domestic façade that reflected the lives of its middle-class readers, creating a new genre out of an old form.

Penny bloods originally had a broad readership, but in the 1860s the focus narrowed, and children became the main target for their readership. There were dozens of titles – The Wild Boys of London (1864–66), The Poor Boys of London (1866), and even The Work Girls of London (1865). In 1865, a 70-part penny dreadful, The Boy Detective, or, The Crimes of London, appeared, with its hero, Ernest Keen, who runs away from home and works for a police inspector, helping him to solve crimes with remarkable efficiency.

As boys became the main protagonists as well as the readers of the penny dreadfuls, legislators and campaigners believed that these susceptible youths required protection from the dubious literary pleasures of such papers. Wily publishers, keen to exploit a growing market for more self-consciously wholesome material, supported this moral outcry against these scurrilous publications. ‘The police court reports in the newspapers are alone sufficient proof of the harm done by ‘penny dreadfuls’’, asserted Alfred Harmsworth, future owner of the Daily Mail, as he launched a new boys’ title, the Halfpenny Marvel, in 1893. ‘It is an almost daily occurrence with magistrates to have before them boys who, having read a number of ‘dreadfuls’, followed the examples set forth in such publications, robbed their employers, bought revolvers with the proceeds and finished by running away from home and installing themselves in the back streets as ‘highwaymen’. This and many other evils the ‘penny dreadful’ is responsible for. It makes thieves of the coming generation, and so helps fill our gaols.’ In August 1895 the MP for Leicester launched a campaign against the ‘grossly demoralising and corrupting character’ of the penny dreadful.

The Halfpenny Marvel was soon followed by a number of other Harmsworth half-penny periodicals, such as The Union Jack and Pluck. At first, the stories were high-minded moral tales, reportedly based on true experiences, but it was not long before these papers started using the same kind of material as the publications they competed against. A.A. Milne once said, ‘Harmsworth killed the penny dreadful by the simple process of producing the ha’penny dreadfuller.’ By the time of the First World War, story magazines such as The Union Jack dominated the market. And the penny dreadful was no more.

The genre has, however, had its highbrow defenders, most notably the English writer G.K. Chesterton, who stated: ‘Sensational novels are the most moral part of modern fiction. Any literature that represents our life as dangerous and startling is truer than any literature that represents it as dubious and languid. For life is a fight and is not a conversation.’

The spirit of the penny dreadful lives on in the horror films and comics of today where zombies, werewolves, vampires and serial killers still entertain and enthral the modern consciousness. They do provide a direct link to those cheap, flimsy gore-fests of the Victorian age.