Complete Nonsense by Edward Lear

Although also an artist and composer, Edward Lear is deservedly best-known for his nonsense in all its many forms: songs, stories, poems, drawings, recipes, alphabets and limericks, a form which he popularized. Described by Lear as simply ‘innocent mirth’, his Complete Nonsense is not only an experience in the absurd, but reveals much about children’s literature and culture of the nineteenth century.

It cannot be denied that Complete Nonsense is above all intended to entertain. The sudden occurrence of the unexpected is generally regarded to be among the most successful ways of generating comedy, and Lear takes this to an extreme. All bets are off when the reader of Nonsense Cookery, instructed in the art of making of an “Amblongus Pie”, is finally directed to “serve up in a clean dish, and throw the whole out of the window as fast as possible”. Likewise, the reader cannot possibly predict that the eponymous Four Little Children would “return immediately to their boat with a strong sense of underdeveloped asthma”. In the limericks, which account for a large portion of Lear’s output, there is no logical connection between the location by which the character is identified (“Old Man of the Hague”), their state (“whose ideas were excessively vague”) and the action (“he built a balloon to examine the moon”). Each element is linked by rhyme rather than rationale. Such unpredictable and incongruous twists and turns are Lear’s most consistent way of ensuring his stories and songs elicit a humorous response.

For the same reason he frequently employs fanciful made-up vocabulary, the most famous of which is “runcible”: the “runcible spoon” from The Owl and The Pussycat inspired so much curiosity that many different, and contradictory, rumours circulated regarding the origin of the neologism. As well as completely invented terms, such as “slobacious”, “beasticles” and “scroobius”, Lear also engaged in witty word-play at all points along the spectrum of sophistication. Two of his characters, for example, leave home to play “battlecock and shuttledore”, a spoonerism of the early sport battledore and shuttlecock. Two others, searching for sage to season their stuffing, are told that they can find some on the hill, and indeed, upon climbing up “among the rocks, all seating in a nook, They saw that Sage a-reading of a most enormous book”.

For the same reason he frequently employs fanciful made-up vocabulary, the most famous of which is “runcible”: the “runcible spoon” from The Owl and The Pussycat inspired so much curiosity that many different, and contradictory, rumours circulated regarding the origin of the neologism. As well as completely invented terms, such as “slobacious”, “beasticles” and “scroobius”, Lear also engaged in witty word-play at all points along the spectrum of sophistication. Two of his characters, for example, leave home to play “battlecock and shuttledore”, a spoonerism of the early sport battledore and shuttlecock. Two others, searching for sage to season their stuffing, are told that they can find some on the hill, and indeed, upon climbing up “among the rocks, all seating in a nook, They saw that Sage a-reading of a most enormous book”.

Satire also plays its part in Lear’s comedy. Although he insisted that “in no portion of these Nonsense drawings have I ever allowed any caricature of private or public persons to appear”, he still found ways to poke fun at features and characters of real life. Some of the ribaldry is self-directed, with a high proportion of the caricatures and limericks focusing on characters with large or ridiculous noses:

“There was an Old Man with a nose,

Who said, “If you choose to suppose

That my nose is too long, you are certainly wrong!”

That remarkable Man with a nose”

In the autobiographical How Pleasant to Know Mr Lear, the poet himself acknowledges that:

“His mind is concrete and fastidious,

His nose is remarkably big;

His visage is more or less hideous,

His beard it resembles a wig”.

One of the most important relationships in Lear’s life was his friendship, which is said to have bordered on obsession, with Sir Franklin Lushington, a barrister and judge. When the Four Little Children spot “somebody in a large white wig, sitting on an arm-chair” which actually turns out to be “the co-operative Cauliflower”, we might wonder whether this is Lear lightly teasing his old friend. And in telling his young audience that “you have only not to look in your geography books to find out all about” the places he describes, Lear is hinting that not all useful knowledge need be learnt in the formal environment and manner usually associated with education.

In fact, in addition to the “innocent mirth” of Complete Nonsense, it also has evident educational value itself. The advanced vocabulary, as well as its historical and cultural references, indicate the type of child the author imagined reading his work. Talk of Vitruvius, Homer and Xerxes (often when Lear seems lost for another word beginning with X) would not have been lost on the “the great-grandchildren, grand-nephews, and grand-nieces of Edward, 13th Earl of Derby” to whom the first book was dedicated. And yet there is also much that is more readily accessible in the nonsense writings too. Perhaps the most comprehensible of Lear’s many forms are his alphabets, which are largely devoid of neologism and avoid random jumps between subjects. Each short poem focuses on a word beginning with a letter of the alphabet, a model still used today in even the most stringently academic children’s books:

“L was a lily,

So white and so sweet!

To see it and smell it

Was quite a nice treat””

“R was a rattlesnake,

Rolled up so tight,

Those who saw him ran quickly,

For fear he should bite.”

As well as this straightforwardly educational content, Lear’s nonsense also conceals a number of complex ideas about society and identity. Although told with fanciful language and impossible narratives, his stories and songs convey real and important human emotions including love, curiosity and insecurity. The Dong with the Luminous Nose tells the tale of unrequited love:

“The Dong [who] was happy and gay,

Till he fell in love with a Jumbly Girl

Who came to those shores one day.

…

For day and night he was always there

By the side of the Jumbly Girl so fair,

With her sky-blue hands and her sea-green hair;

Till the morning came of that hateful day

When the Jumblies sailed in their sive away,

And the Dong was left on the cruel shore

Gazing, gazing for evermore.”

The Nutcrackers and the Sugartongs, despite the evident impossibility of the situation, expresses an all too authentic concern about one’s own ability, a desire for adventure and the satisfaction of achievement:

“The Nutcrackers sate by a plate on the table;

The Sugar-tongs sate by a plate at his side;

And the Nutcrackers said, “Don’t you wish we were able

Along the blue hills and green meadows to ride?

Must we drag on this stupid existence forever,

So idle and weary, so full of remorse,

While everyone else takes his pleasure, and never

Seems happy unless he is riding a horse?

…

The Frying-pan said, “It’s an awful delusion!”

The Tea-kettle hissed, and grew black in the face;

And they all rushed downstairs in the wildest confusion

To see the great Nutcracker-Sugar-tong race.

And out of the stable, with screaming and laughter

(Their ponies were cream-colored, speckled with brown),

The Nutcrackers first, and the Sugar-tongs after,

Rode all round the yard, and then all round the town.”

The overcoming of one’s own insecurities and of one’s critics is a constant theme throughout the nonsense stories and poetry. Just as the Nutcrackers and Sugar-tongs prove the Frying-pan wrong, so too do many other characters defy the naysayers. Interestingly, their triumphs are often paired with, or the result of, a journey far away. The last words from these particular kitchen utensils is “We will never go back anymore!”, a sentiment echoed throughout many stories. The wall-climbing Mr and Mrs Discobbolos, having decided that to “never go down again” happily pass their life “far away from hurry and strife”. “They never came back” is a repeated motif in Calico Pie, and in The Pelican Chorus, the leading pelican literally flies the nest, leaving her fellows remarking that:

“She has gone to the Great Gromboolian Plain,

And we probably never shall meet again.

She dwells by the stream of the Chambly Bore,

And we probably never shall see her more.”

Lear himself travelled frequently from the age of thirty, most often visiting Italy, where he eventually settled at the San Remo home he nicknamed Villa Tennyson. The youngest surviving child of 21 and raised by his elder sister after his father’s bankruptcy, his early years cannot have been easy. In view of this childhood upheaval, it is easy to see Lear’s departure for Italy as an escape from negative influences and memories at home, a hypothesis that seems all but confirmed by the theme of separation and distance that persists throughout even his most light-hearted work.

Rainbow Lorikeet

A similarly weighty topic sometimes veiled by the frivolity of Lear’s style is that of death. Death has its place in many of the nonsense writings, but in none more so than The History of the Seven Families of Lake Pipple-popple. In this story, the parents of seven families, each a different species of animal, send their young off into the wild with one clear warning. For the parrots, it is “‘if…you find a Cherry, do not fight about who should have it”, for the geese “whatever you do, be sure you do not touch a Plum-pudding Flea”, and so on. On venturing into the wide world, each group of siblings eventually falls foul of the very trap illustrated for them by their parents. In fact, all the young animals die, and on hearing the news the parent animals commit a sort of ritual suicide: “they filled the bottles with the ingredients for pickling, and each couple jumped into a separate bottle, by which effort of course they all died immediately, and become thoroughly pickled in a few minutes.”

Lear had started his artistic career as an ornithological draughtsman for the Zoological Society and although, rather unusually, he drew birds from the live animals rather than skins, he would no doubt have been used to seeing dead specimens on a regular basis. In general, Victorian society was far from shy when it came to the subject of death, exemplified by the Queen’s decades of elaborate mourning for Albert. The mortality rate, although much improved from the preceding centuries, was far higher than today’s, especially among children, and many more deaths occurred in the home surrounded by family. It was thus an inescapable part of life, as indeed it is.

As evidenced by the references to the ancient world, the children for whom Lear writes would have grown up on stories of the Trojan war, where death abounds with ruthless finality. Contemporary children’s literature, by the likes of Lewis Carroll, William Blake and later J.M. Barrie, also carry a similar undercurrent, with characters well aware “that sudden death might be at the next tree, or stalking him from behind”. These writers have by no means been cast from the canon, but their popularity has been superseded by modern children’s books and entertainment, which by and large avoid the explicit theme of death.

It is difficult to image a parent today choosing The History of the Seven Families as a bedtime story for their child. Simple reasoning might say that it runs the risk of frightening or upsetting them, and in the short term this may be true, but omitting the concept of death from early development must have long-term effects. How much more terrifying to discover it as an unexpected and unavoidable fact when confronted with the real thing, rather than coming to know the realities of life through story and song. Death gives meaning to life, and Lear provides an important service in introducing it gradually, gently and even with humour in his Collected Nonsense.

Main image: Drawing by Edward Lear from his book ‘Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany, and Alphabets,’ first published in 1871. Credit: The Granger Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

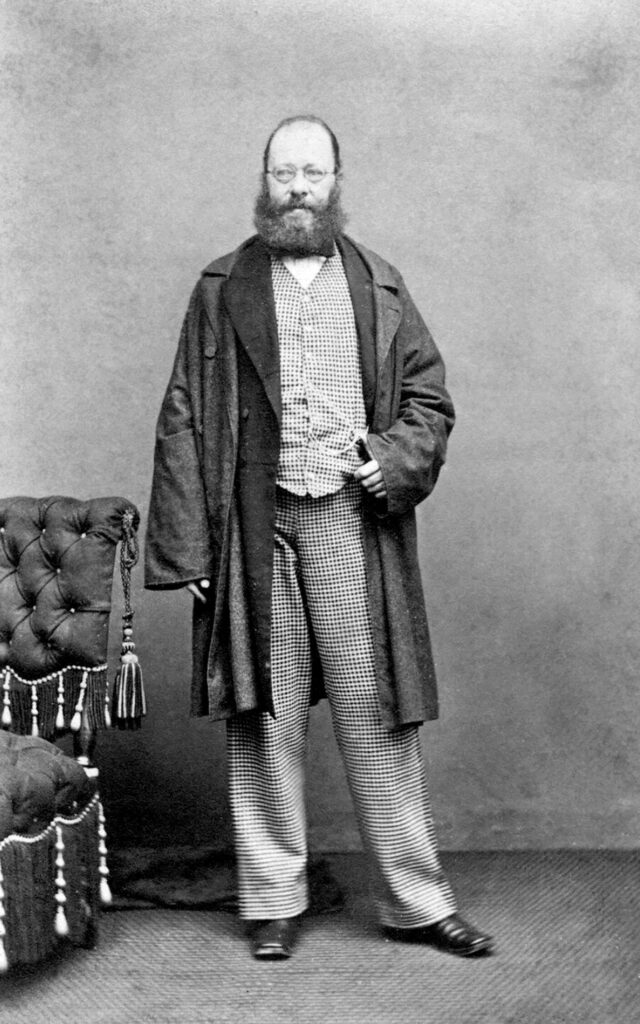

Image 1 above: Edward Lear 1862. Credit: Ian Dagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Rainbow lorikeet, after an illustration by Edward Lear. Hand-coloured lithograph from Georg Friedrich Treitschke’s Gallery of Natural History, Naturhistorischer Bildersaal des Thierreiches, Liepzig, 1840. Credit: Florilegius / Alamy Stock Photo