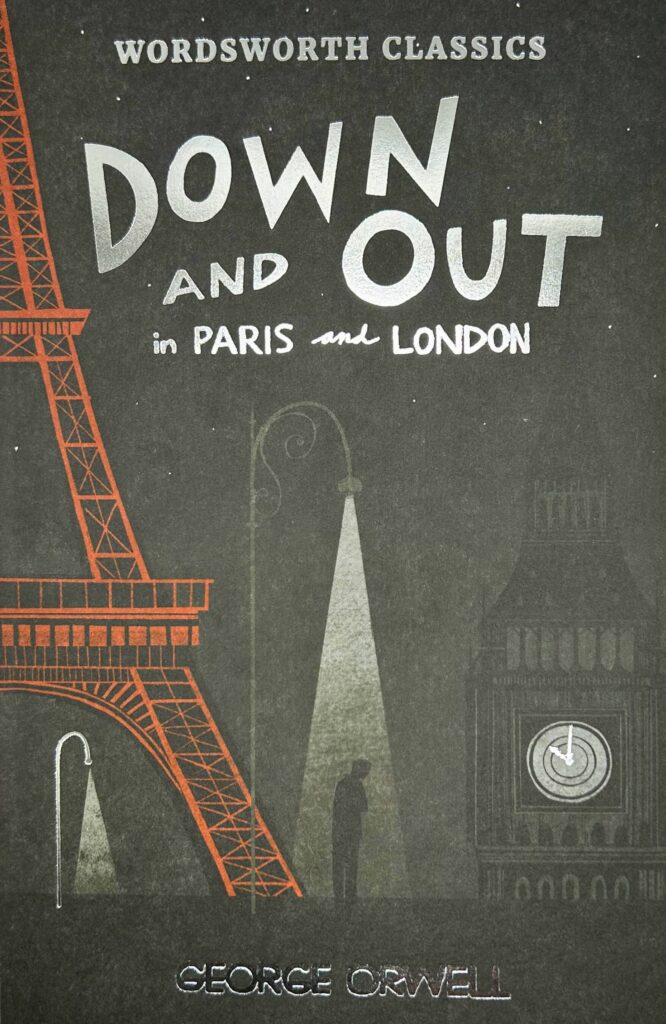

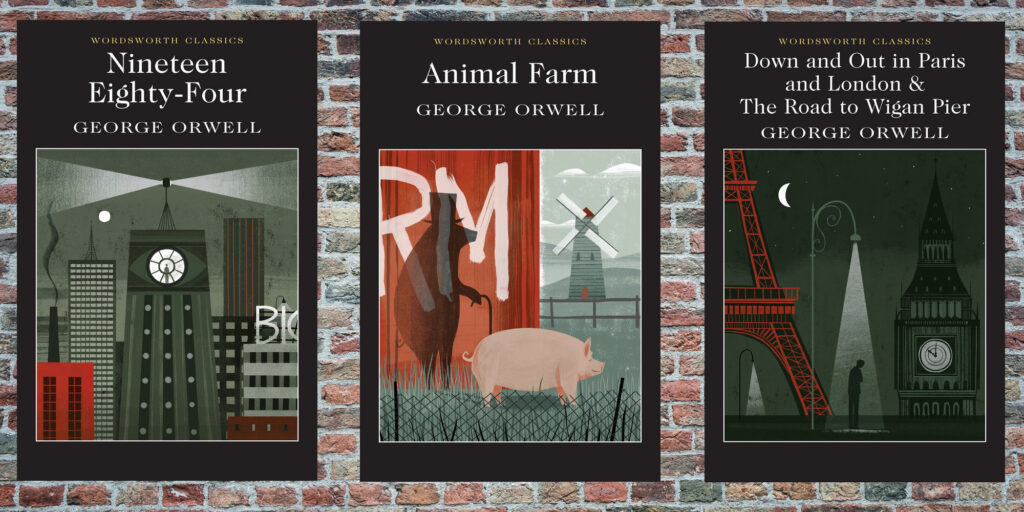

Books by George Orwell

Nineteen Eighty-Four (Collector’s Edition)

New for 2024

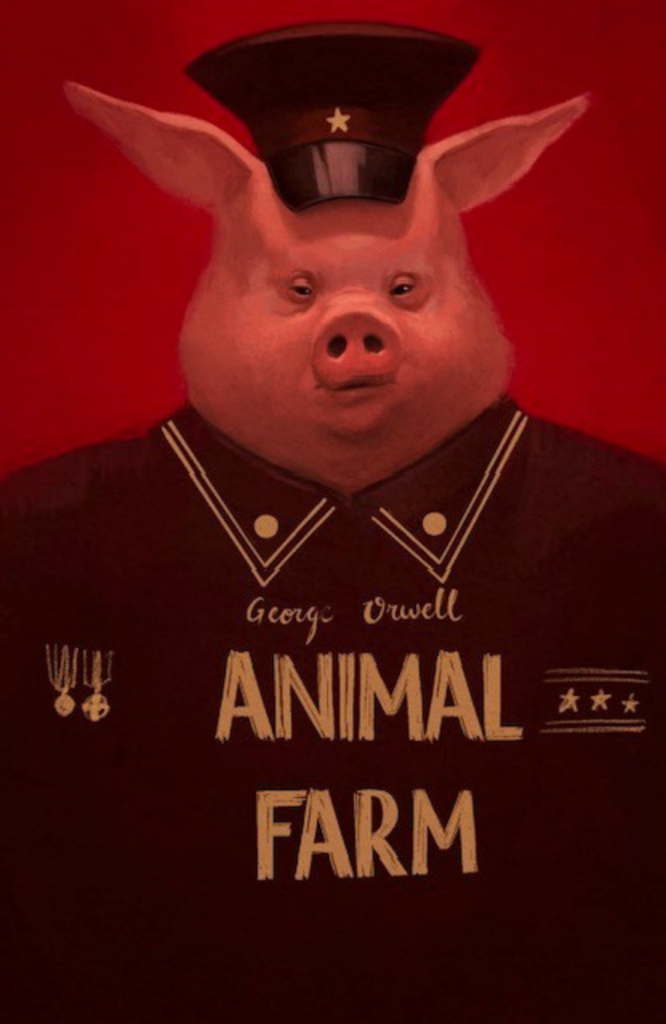

Animal Farm (Collector’s Edition)

New for 2024

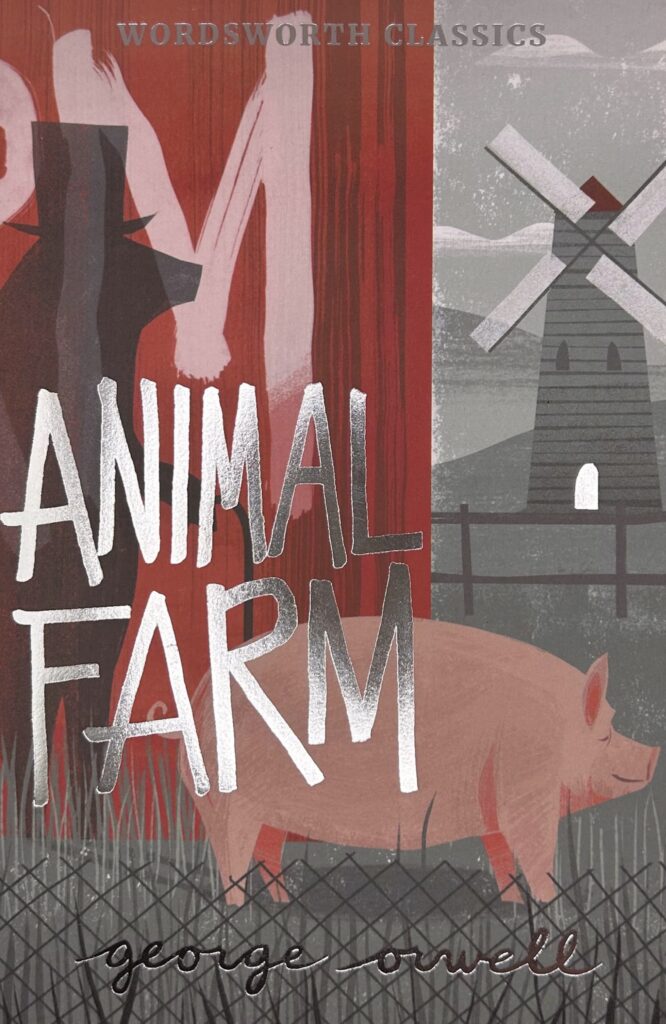

Animal Farm

Classics

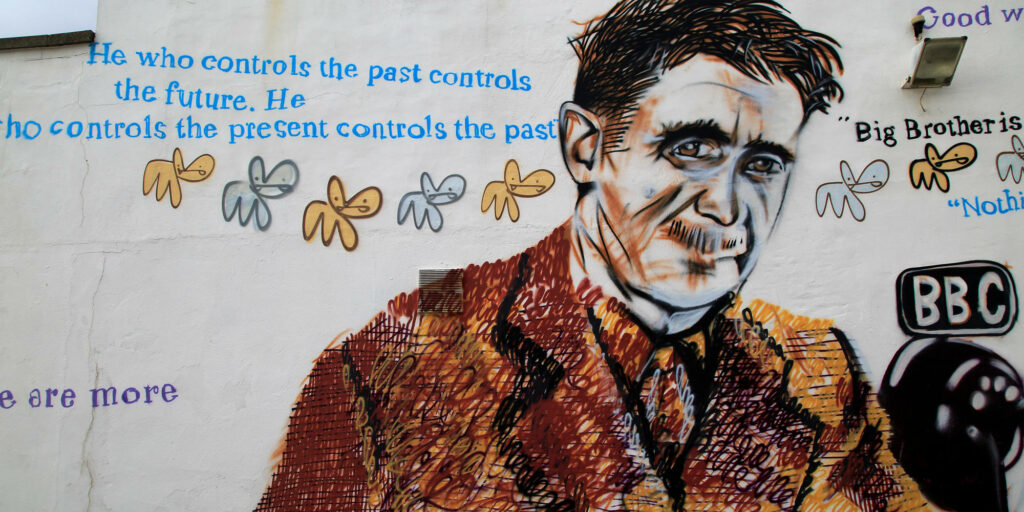

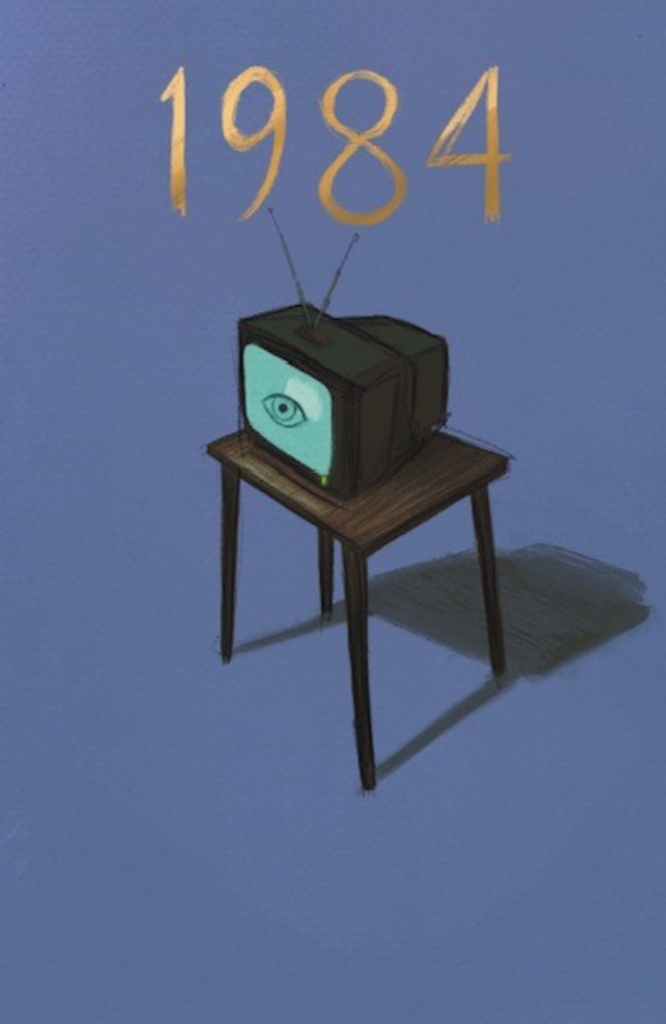

Nineteen Eighty-Four

Classics