The Personal is the Political: Nineteen Eighty-Four

Sally Minogue reflects on the connection between the two in George Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’.

It’s just about a year ago that I began work for the introduction to the new Wordsworth edition of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, a moment I look back to as one of sublime innocence. Subsequently, very many aspects of the novel have resonated in this year where on the one hand the President of the United States mounted a ruthless attack on truth, and on the other, once unimaginable limits on personal freedom were necessarily introduced to save us from the depredations of the Covid virus. At such times of crisis, language itself comes under pressure. Sadly, the word ‘Orwellian’ was brandished by those who flaunted their opposition to mask-wearing or proclaimed conspiracy theories about the virus and the vaccine, as though the totalitarianism Orwell satirised was on the same level as the temporary use of interventionist powers to limit personal freedom in the service of the public good. Orwell would have seen the irony.

It was a less obvious feature of the novel that tugged at my mind as the year unfolded, and whose significance coalesced in a more personal form this month when we had a number of notable family birthdays, which could be celebrated only via Zoom. Suddenly old photographs assumed great power. My sister’s 80th birthday was charted with images starting from our parents’ youth, engagement and marriage, then following her own progress from beautiful baby and toddler through the years of carefree youth, marriage, motherhood and career, grandmotherhood and retirement, and the attendant photographs of we siblings, nephews and nieces and great-nephews and great-nieces, all of us linked in and sharing memories with each other online. Though these photos were captured digitally, enabling us all to share them in our different parts of the country, most of them were not themselves digital images, but print photographs. Those from the earlier part of the twentieth century were often creased and lined like some of the faces depicted there; black and white, or touched up as though they had had make-up applied. Some were tiny, from box cameras. As we all grew older before our eyes, so the photographs reflected changing printing practices and technologies. Time concertina-ed, a life well and fully lived flashed before us, prompting deeper reflections than would have been likely in the rumbustious and joyous party we would undoubtedly have had in different times. This was still a shared experience, but one in which time took on tangibility; it was a digital experience, but one that still reflected the materiality of the photographs, themselves reflecting the materiality of a sometimes distant time and place. We were experiencing the way ‘photographs testify to time’s relentless melt’.[1]

As I was driven in turn to look back at old family letters and what they recorded of the persons and events that had gleamed momentarily on our flat screens, I felt the connection between these personal histories and the larger implications of printed photographs and the handwritten word which Orwell places at the centre of his novel. In what is always a deeply political work, he is novelist enough to use the experience of one human character with whom we can identify, Winston Smith, to foreground the importance of these physical forms of human record. In his day job at the Ministry of Truth, Winston is highly skilled in altering the past, rewriting Times newspaper entries to reflect the current state of political thinking. These ‘postdated’ entries then become the new history, itself open to alteration when current ideology or political reality – for example, whether Oceania is at war with Eastasia or Eurasia – changes again. The old record is consigned to a chute where ‘it would be whirled away on a current of warm air to the enormous furnaces which were hidden somewhere in the recesses of the building’ (30). In one of the novelist’s many imaginative coinages, these chutes are called ‘memory holes’, a phrase which contains an inherent contradiction, a manifestation of the doublethink that is another of the novel’s new namings. The hole down which the once-public record disappears destroys memory rather than preserving it; it creates a hole in the memory. One of Winston’s great battles with his eventual torturer O’Brien is to preserve his own individual memory, which O’Brien seeks to erase.

In the process of his work, Winston once briefly held a newspaper photograph of three well-known ‘conspirators’ against the state; the photograph proves their innocence, by placing them in New York on a date when they had, under duress, confessed to being on Eurasian soil and plotting against Oceania. Five years after their execution, Winston finds, amongst documents sent to him to ‘update’, the newspaper photograph demonstrating that their ‘confessions were lies’ (60):

Winston had not imagined that the people who were wiped out in the purges had actually committed the crimes that they were accused of. But this was concrete evidence; it was a fragment of the abolished past, like a fossil bone which turns up in the wrong stratum and destroys a geological theory. It was enough to blow the Party to atoms if in some way it could have been published to the world and its significance made known. (60-61)

Winston swiftly commits the photograph to the memory hole for the flames to consume; to do otherwise would be to incriminate himself. But at the same time, he commits it to his own memory, reflecting:

It was curious that the fact of having held it in his fingers seemed to him to make a difference even now, when the photograph itself, as well as the event it recorded, was only memory. Was the Party’s hold upon the past less strong, he wondered, because a piece of evidence which existed no longer had once existed? (61)

Orwell’s syntax here accentuates conceptual vertigo with which Winston struggles – ‘existed no longer’ placed antithetically right next to ‘had once existed’. When it comes to O’Brien’s attempt to subdue even Winston’s inner consciousness, it is the gap between those two states of time that he exploits. By briefly producing the actual newspaper photograph once again and flaunting the ‘oblong slip of newspaper’ before his victim, long enough for him to recognize ‘the photograph’, he increases Winston’s sense of mental fracture:

‘It exists!’ [Winston] cried.

‘No,’ said O’Brien.

He stepped across the room. There was a memory hole in the opposite wall. O’Brien lifted the grating. Unseen, the frail slip of paper was whirling away on the current of warm air; it was vanishing in a flash of flame. O’Brien turned away from the wall.

‘Ashes,’ he said. ‘Not even identifiable ashes. Dust. It does not exist. It never existed.’ (189-190)

In this replaying by O’Brien of Winston’s own destruction of the photograph, both the reader’s and Winston’s belief in personal memory are tested. When Winston immediately protests, ‘ “But it did exist! It does exist! It exists in memory. I remember it. You remember it.”’ O’Brien retorts, ‘ “I do not remember it”’. This reduces Winston to ‘a feeling of deadly helplessness’ as he considers the possibility that such ‘lunatic dislocation could really happen’. (190) The long duel between Winston and O’Brien brings us up close to the Party’s determination to exert complete control. As readers, we share Winston’s sense of helplessness, whilst at the same time understanding that no external ideological cause is driving this exertion of power. Power itself is the ideology.

However we interpret the outcome of the final struggle between Winston and O’Brien, Orwell leaves us in no doubt about the political as well as the personal significance of the traces left by human lives. The memory hole reminds us that these are important enough for the Party to want to destroy them. While Winston alters larger histories within the Ministry of Truth, at home he is committing the ultimate act of dissent by recording his individual thoughts in his own handwriting, in pen and ink, on the creamy blank pages of the book he has bought in a junk shop. ‘This [act of writing a diary] was not illegal’, we are told, ‘but if detected it was reasonably certain that it would be punished by death’ (7). At this very early stage of the novel, we are left to infer why it is deemed so dangerous. The presence of the spying telescreen in the room, the fact that Winston has to compose his face when he turns towards it, and his use of an alcove just out of its range to write his diary, quickly reveal that any inner thoughts which might be construed as hostile to the Party must be kept hidden. As the novel progresses, we learn that in fact any autonomous inner thoughts are inherently antithetical to the Party. Being a thinking individual is antithetical to the Party. Yet still, Winston puts pen to paper and writes, in a hopeless act of communication – hopeless because even as he does so, Winston knows that ‘He was a lonely ghost uttering a truth that nobody would ever hear. But so long as he uttered it somehow the continuity was not broken’ (23). He dedicates his writing ‘to a time when thought is free … to a time when truth exists, and what is done cannot be undone’ (23).

At this point, Winston is still innocent of what is to come; but whatever happens to his own consciousness in the novel, that moment of faith remains, written down in his own hand in a form that is more difficult to alter than any of the Times articles he rewrites. What he writes in his Diary can, of course, be destroyed, consigned to the memory hole, fulfilling in the world of the novel O’Brien’s prediction that ‘“You will be lifted clean out of the stream of history”’ (195). But by fiction’s sleight of hand, here we are, still reading it. Winston’s history is not lost to us; that is the one hope the novel offers. In our digital world, where images are now so easy to alter that they have lost their reliable connection to the moment in time and place to which they refer, Orwell’s novel re-asserts the power of the material human record. However small and seemingly insignificant the traces left by a life, in the family photograph, in the writing still connected to the human hand, they connect us to a particular time, place and human materiality.[2] As we used to say in the ‘60s, the personal is the political.

All page references are to the current Wordsworth edition of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

For those interested in reading more about photography, the Sontag and Barthes texts mentioned are both extremely interesting, and less difficult than the authors’ reputations suggest.

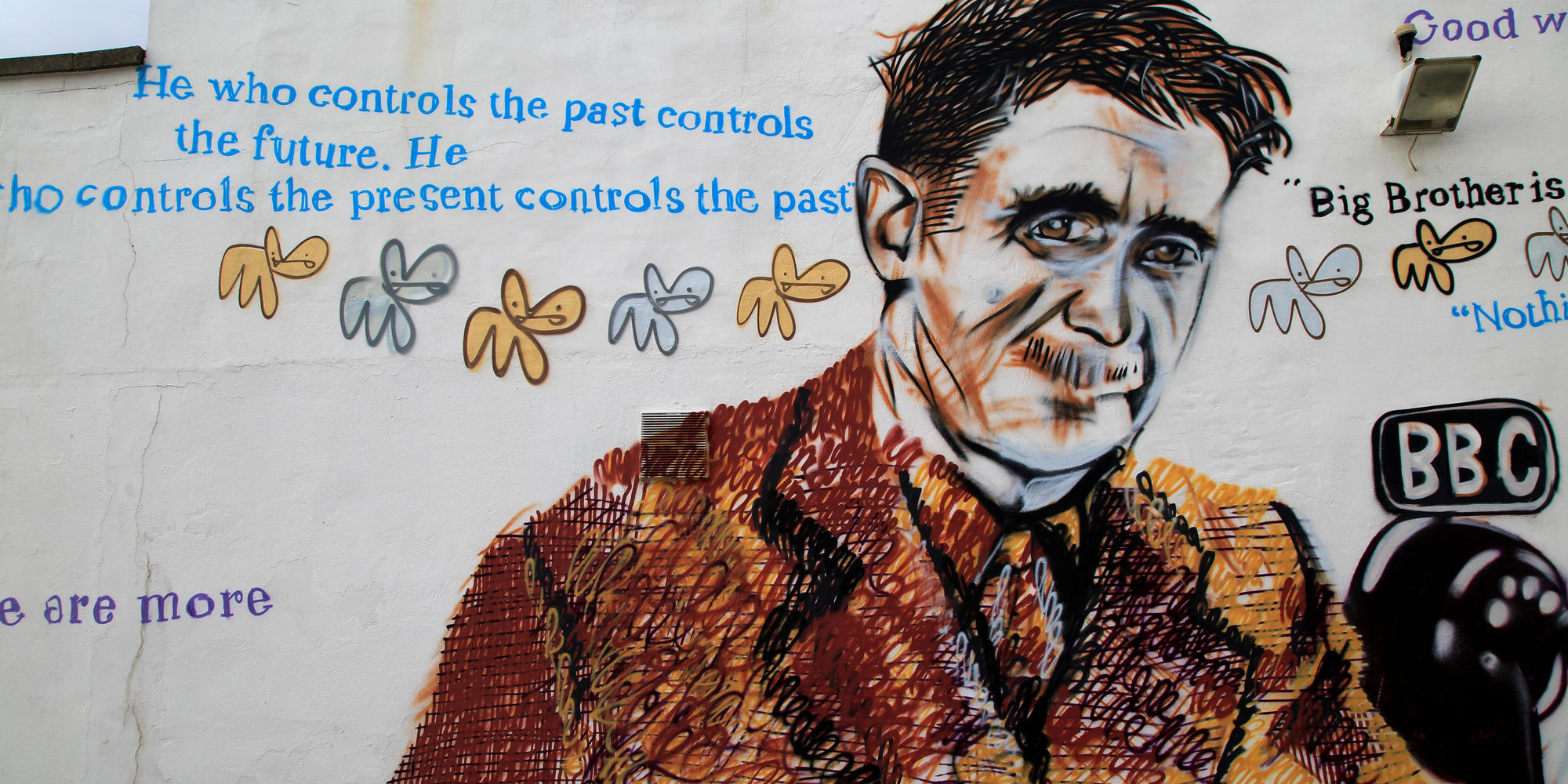

Image: George Orwell mural Southwold, Suffolk, by Charles Uzzell Edwards Credit: Geogphotos / Alamy Stock Photo

[1] Susan Sontag, On Photography, London, Penguin, 1979, p. 15.

[2] Roland Barthes, writing about print photographs developed from film, reminds us that ‘the photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here.’ Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1980), trans. Richard Howard, London, Vintage, 2000, p. 80

Books associated with this article