Empire

‘I shall try to fly by those nets’: Sally Minogue offers a final reflection on literature and Empire.

If we needed a reminder of the ability of the British to erase the blood-steeped events of our imperialist history, look no further than the late Queen’s funeral. Charlotte Higgins, writing for The Guardian (online September 19), noted acutely that where there is a lacuna, there lies an anxiety: ‘that the Commonwealth was so lavishly invoked during the funeral rites was a reminder that the angry ghosts of empire are massing outside the palace and cathedral doors’. Throughout the ceremony, Commonwealth was elided with Empire, without a note of irony. There was one mutter about ‘difficulties’ but otherwise one might have thought that there’d been a seamless, painless slide from British rule over the many countries represented, to their independence. And the presence of their many representatives colluded in this view, though there was an occasional nod in the clothing of leaders to their national identity. 15 of the Commonwealth realms (out of 56) still have the British monarch as their titular head of state, including, extraordinarily, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. Antigua, mentioned in my recent blog on Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, retains the monarchy. The monarch in these Commonwealth realms is represented by, usually, a Governor-General – literally the viceroy, the substitute for the king. Of course, as in the United Kingdom itself, the monarch’s constitutional powers are purely symbolic. This was written into the Balfour Agreement (1926): our present King has no jurisdiction whatsoever over the remaining members of the Commonwealth who recognise him as head of state. Similarly, they have no obligation of any kind to the British Government*. Though these connections are symbolic, they are woven heavily into the fabric of British culture. And at times – as with the Queen’s funeral – the public may be forgiven for forgetting that they are only symbolic, because the rhetoric and panoply of the occasion encourages them to see them as meaningful. They may also be forgiven for thinking that the Commonwealth as a political entity has some constitutional link with the United Kingdom. It doesn’t.

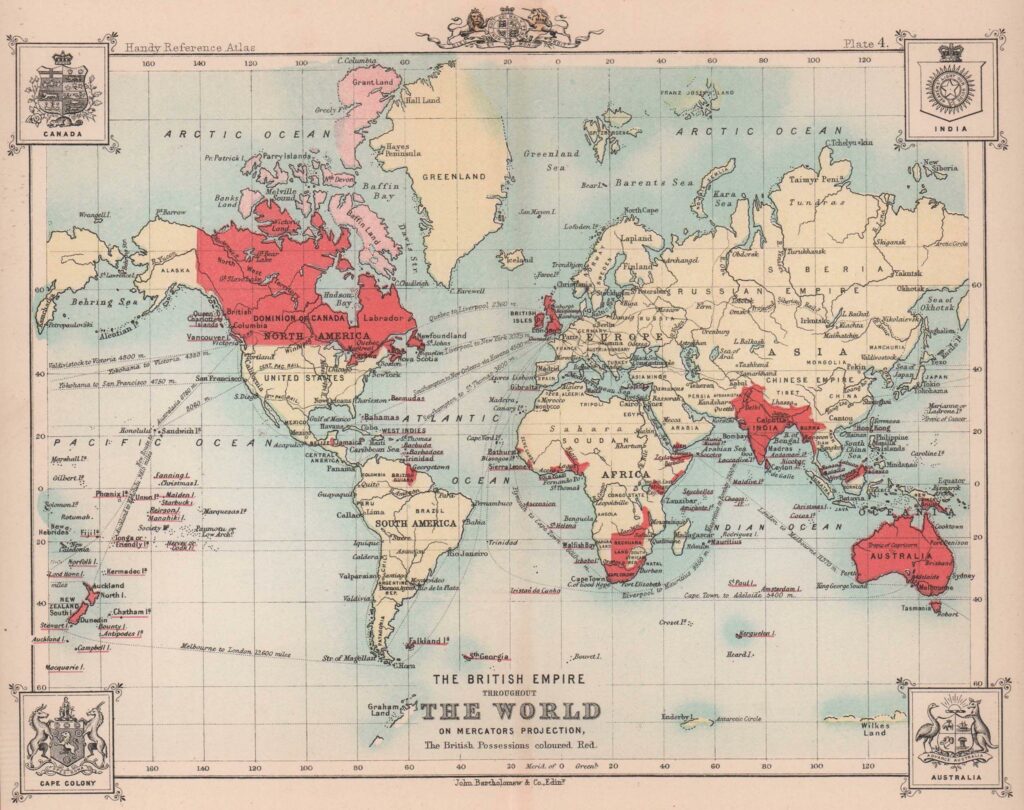

The British Empire 1893

What, you might be wondering, has this to do with fiction? Well, my last three blogs have tried to answer that question. But here I want to open up the discussion, air the oppositional view, and consider whether literature really matters in current debates about Empire – or to put that in reverse, whether Empire really matters in debates about literature. Regular readers of my blog will know which direction I’m coming from, but I’ll also play devil’s advocate.

To take from Wordsworth authors an example at the extreme end of the spectrum: John Buchan (1875-1940) is generally recognised as upholding values of Britishness, and therefore Empire. No surprise there. But it is interesting to look in more detail at the way in which, for example, Greenmantle (1916, in Wordsworth’s The Complete Richard Hannay Stories) explores anxieties about the threat of Islam in the First World War. Its hero Hannay, invalided out of the Battle of Loos, is recruited by the Foreign Office ‘to discover and neutralise a German-inspired plan in the Middle East to galvanise the Muslim world and ignite a powerful “Jehad” against the Allies’. This quotation (and subsequent information) is from Keith Jeffery’s 1916: A Global History (192-3), and Jeffery shows throughout this work, most notably in the chapter on Gallipoli, the fear the British had about a possible Islamic uprising. The head of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, Sultan Mehmet V (allied with the Germans), who ‘as caliph claimed leadership of Muslims throughout the world’ (13), issued a fatwa at the start of the First World War against French, English and Russian forces (179). Over 60 million of the 300 million inhabitants of British-ruled south Asia were Muslims. Could there be a pan-Islamic mobilisation against the Allies? This came down, at a local level in Gallipoli, to the decision to replace two Punjabi (Muslim) battalions with Gurkhas, for fear of uncertain Punjabi loyalties. (27)

Now, when we read Greenmantle, does the average reader ever think about that? Or indeed whether Hannay’s values are right? In this rollicking adventure, and after the establishment of Hannay as hero extraordinary in The Thirty-Nine Steps, we don’t (unless we are historians of Empire) stop to think about the calculations the British were making about their imperial hold on power in Asia. But calculating they were, even as they were using those Asian troops to fight and die for them – possibly the best demonstration of imperial power. One wonders what an individual Muslim soldier, fighting ‘for’ the British against fellow-Muslims, might have thought. Of course, such thoughts are not represented.[1] Meanwhile Buchan’s Greenmantle, published in the midst of the First World War, pulled its readers along on an exciting story, as it still does, carrying an imperialist narrative in its wake.

But with Buchan, we know where we are; that he ended up as Governor-General of Canada from 1935 to 1940 just completes the circle. More interesting, perhaps, are those works whose reference to imperialism is hidden, as in the examples I have explored in previous blogs. Many of these come from the nineteenth century, perhaps the greatest age of British fiction, and it is not surprising that the most powerful literary emanations of that age reflect its dynamics of power. Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1816-1855, Jane Eyre published 1847) has been relentlessly investigated for its representation of Mrs Rochester, both in terms of its misogyny and its possible racism. Jean Rhys’s The Wide Sargasso Sea (1890-1975; 1966) is the best possible creative counterpoint to Brontë’s novel. If we read the two together, we get a complex picture without reducing the power of either. Similarly, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) has called forth the postcolonial novel Foe (1986) by South African Nobel laureate J. M. Coetzee (b. 1940).

So, the Empire writes back. And this way fiction remains rich and non-reductive. But what of the argument that fiction is simply fiction, and should be read as such, without consideration of political dimensions, especially if these are hidden so far below the surface of the narrative that it takes a literary critic of superhuman powers of hewing to reach them? And after all, literary critics are not known for their powers of hewing. One argument against the retrospective analysis of earlier works of fiction from a later politically-informed viewpoint, is that a sort of anachronism is going on in reverse. Attitudes, knowledge even, that the writer concerned could not have shared are used as an index against which to measure that writer’s worth. In each of my blogs, on Kipling, Conrad and Austen, I have tried to demonstrate that each writer was in fact aware of some of the issues of Empire raised. But there is sometimes something soulless in looking for that buried issue, in the smallest detail, and magnifying it beyond the span of the world of the novel itself.

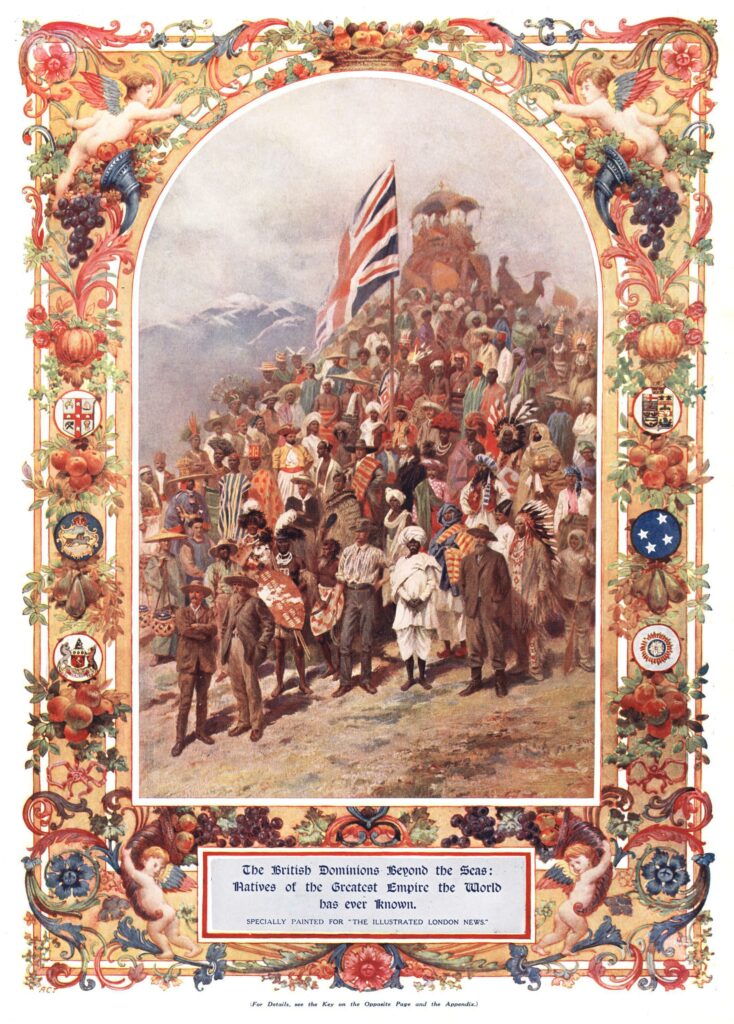

The British Empire Magazine 1910

I’d like to end with an example from the other end of the ‘Empire’ spectrum to Buchan: James Joyce. Joyce’s dates, 1882-1941, match Buchan’s very closely. Yet in 1916, just as the frankly imperialist Greenmantle was published, the full edition of Dubliners was also published, Joyce himself was self-exiled in Trieste having chosen a European rather than an Irish identity, and he had begun to write his great work Ulysses, the early episodes of which were published in 1918. Joyce’s understanding of the ideas we have been discussing goes behind the issues of English imperialism to that of Irish national identity, and he imperiously dismisses both in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Joyce’s view, held throughout his creative life, was that the artist must stand outside any restrictions, borders, identities placed upon him. The pull of Irish identity, and particularly the identity of the Irish writer, may have had a particular effect here. Though he speaks it fictionally via Stephen, Joyce certainly lived by the precept: ‘When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight … I shall try to fly by those nets.’

Joyce was born in a country which was itself the subject of English imperial power. But his strength as a writer is to resist both that power and the siren song of Irish national identity. In Ulysses, his hero is an Irish Jew, an inherent outsider/insider. When racism rears its head in the Cyclops chapter, Joyce weaves a complicated story of attack and defence around Bloom. His mode is as ever intertextual, ironic, never allowing a prevailing view. Yet the outcome of the chapter is to undermine the ‘citizen’ who utters and embodies anti-Semitic views. In the end Bloom’s insistence that ‘A nation is the same people living in the same place’ provokes the citizen to ask of Bloom, ‘“What is your nation if I may ask?” Bloom’s reply: ‘“Ireland. … I was born here. Ireland.”’

This exchange is replicated in countless exchanges in Britain a hundred years later. People who were born here being asked where they are ‘really’ from. This is a direct result of both the trans-national migrations of Empire (often encouraged by the ‘mother’ state, as with Windrush) and the attitude, like that of Joyce’s citizen, that race somehow supersedes one’s place of birth and therefore negates it. Sathnam Sanghera’s Empireland is a witty, self-deprecating but utterly damning account of the workings of the British Empire on those who were its ‘subjects’. Dip into a few of its pages and you won’t come out quite the same. Sanghera looks at the complications of imperialism for its subsequent generations, both the ‘ruling’ and the ‘ruled’. It is entirely to Joyce’s credit that he understood back in 1916, when few others had that understanding, not just the wrongness of one country’s taking authority over another by force, but also the wrongness of a purely nationalistic reaction to that. Not only that, the joyful playfulness and intertextuality of his writing threatens any monolithic narrative.

Taking my cue from Joyce, who to my mind really does ‘fly by the nets’ of any form of national identity, I commend most those works that ask questions of Empire. That includes Heart of Darkness, for all its flaws, alongside, yes, even Kipling’s Kim. Neither gives a straightforward account of the imperialist enterprise. Yet both works are driven by a powerful narrative which leads us away from rather than towards any questioning. The power of narrative to seduce is, at bottom, why we all read. We love the story, the adventure, the relationships, the world that we enter. That is precisely what makes novels so powerful, and why they can carry ideas and ideologies – indeed must do so, as cultural emanations of their moment in time. Part of the pleasure of reading is to be carried along in their narrative stream. But another pleasure is to be observant of the complicated threads I have been trying to untangle in this short series. I honestly think we can enjoy both.

*A Facebook reader of the original published draft of this blog has kindly pointed out the counter-example of Governor-General of Australia Sir John Kerr’s dismissal of elected Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, November 11th 1975. Kerr was at the time anxious to demonstrate that he did not inform or consult the Queen abot his decision, but papers made public in 2020 shows a prior correspondence with the Queen’s Private Secretary Sir Martin Charteris about the possibility of this dismissal. There was also discussion with the then Prince Charles.

Jane Austen: Mansfield Park

Charlotte Brontë: Jane Eyre

John Buchan: The Complete Richard Hannay Stories

John Buchan: The Thirty-Nine Steps

Daniel Defoe: Robinson Crusoe

J. M. Coetzee: Foe

Jean Rhys: The Wide Sargasso Sea

Keith Jeffery: 1916: A Global History, Bloomsbury, 2015

Sathnam Sanghera: Empireland, Viking, 2021

[1] I have mentioned, in a previous blog on the Nobel Prize, Abdulrazak Gurnah’s After Lives. This novel looks, inter alia, at Muslim Africans fighting for Germany in the First World War.

More information on the life and works of John Buchan, visit The John Buchan Society website

Main image: British India: An English family enjoy the comforts of the British Empire. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Images above:

-

Map of the British Empire 1893 Credit: Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

-

The British Empire Magazine Plate 1910. Credit: Retro Ad Archives / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

Ulysses

James Joyce

The Complete Richard Hannay Stories

John Buchan

The Thirty-Nine Steps

John Buchan

Dubliners

James Joyce

Dubliners (Collector’s Edition)

James Joyce

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

James Joyce

Robinson Crusoe (Collector’s Edition)

Daniel Defoe

Robinson Crusoe

Daniel Defoe

Jane Eyre (Luxe Edition)

Charlotte Brontë

Mansfield Park (Collector’s Edition)

Jane Austen