The Real Count Dracula

Dr Stephen Carver looks at the most famous vampire of them all.

When Bram Stoker died after a series of strokes on April 20, 1912, his obituary in The Times made only a single and cursory reference to Dracula noting that ‘He was the master of a particularly lurid and creepy kind of fiction’. The book that we regard as Stoker’s masterpiece, his enduring contribution to global popular culture, is lumped in with his ‘other novels’ (which were nothing special), his journalism, and an interest in musical comedy. It is his Personal Reminisces of Henry Irving (1906) that is cited as his ‘chief literary memorial’. In fact, the whole obituary is pretty much about the colourful actor Sir Henry Irving, and Stoker’s long association with him as a close friend and business manager: ‘Few men have played the part of fidus Achates to a great personality with more gusto.’ Even in death – Irving had gone to his grave in 1905 – the monolithic presence of the great tragedian completely eclipsed the author of Dracula.

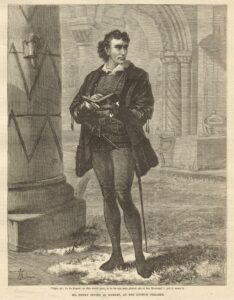

Largely forgotten nowadays, Irving was a giant of the Victorian stage; a national treasure to some, a grotesque ham to others, he was a living legend either way who became the first actor ever to be knighted in 1895. Intense and narcissistic, Irving was notoriously demanding and difficult to work with. His frequent collaborator – and sometime lover – Ellen Terry described him as ‘half-devil, half-saint’, and when he died even The Time had to admit that his melodramatic style and tendency to rewrite Shakespeare did not suit all tastes:

In no single case was his own performance universally accepted as even good … Some found his marked mannerisms insuperable obstacles to enjoyment or sympathy; some objected to an actor who, whatever he did or did not, always insisted upon having his own reading of every part and every play.

Sir Henry Irving as Hamlet

(George Bernard Shaw described Irving’s interpretation of Hamlet as ‘performing Hamlet with the part of Hamlet omitted’.) These mannerisms included wild, exaggerated gestures, stentorian diction, and a habit of thunderously stamping his foot on the boards at regular intervals to ensure that all eyes remained on him during the play. At the Lyceum, which he managed from 1878 to 1902, Irving held court like a king, gathering around him the great and the good of London Society for lavish dinners after a performance. His prejudices were many and his whims capricious. Stoker adored him.

Stoker had first seen Irving perform in 1867, inspiring a lifelong love of theatre. They later met in Stoker’s native Dublin in 1876. Stoker had written two very favourable reviews of Irving’s Hamlet at the Theatre Royal for the Dublin Evening Mail, and the actor had invited him to dinner. Part of the evening’s entertainment took the form of recitations. Irving chose Thomas Hood’s gothic poem ‘The Dream of Eugene Aram’, which Stoker later described in his Personal Reminisces:

Such was Irving’s commanding force, so great was the magnetism of his genius, so profound was the sense of his dominance that I sat spellbound … That night Irving was inspired. That night for a brief time, in which the rest of the world seemed to sit still, Irving’s genius floated in blazing triumph above the summit of art. There is something in the soul which lifts it above all that has its base in material things. If once only in a lifetime the soul of a man can take wings and sweep for an instant into mortal gaze, then that ‘once’ for Irving was on that, to me, ever memorable night.

The recitation concluded, Irving ‘collapsed half fainting’. By his own admission Stoker was overcome, writing that ‘after a few seconds of stony silence following his collapse I burst out into something like a violent fit of hysterics.’ Irving at this point magically recovered and went to his dressing room, returning with an autographed photograph of himself inscribed ‘My dear friend Stoker – God bless you! God bless you!’ According to the actor’s grandson, Laurence Irving, the whole event had been contrived to hook and land Stoker. Irving was by then planning his takeover of the Lyceum from current manager Sidney Frances Bateman, and was assembling his team. Superfan Stoker was being groomed for one of the top slots in the organisation. When Irving took over the Lyceum, the newly married Stoker left Dublin and the Irish Civil Service to become his business manager in London, a post he held until Irving’s death almost thirty years later.

Born in the affluent Dublin suburb Clontarf in 1847, Stoker was the epitome of male middle-class Victorian respectability. The son of an Anglo-Irish Civil Servant, Stoker distinguished himself at Trinity College athletically and academically. He was a track and field champion, a capped rugby player, and President of both the Philosophical and Historical Societies, graduating BA in 1870 (he later claimed his degree was in Pure Mathematics but there’s no record of this at the university). He followed in his father’s footsteps and went to work in Dublin Castle as a clerk, quickly rising to become Inspector of Petty Sessions, overseeing magistrates’ courts across Ireland. He made a good marriage in 1878, stealing the twenty-year-old beauty Florence Balcombe away from his university friend Oscar Wilde, to whom she had been engaged. The couple had one child, Noel, born a year later. He also wrote, contributing reviews and the occasional short story to the Dublin Evening Mail, the Halfpenny Press (which he also edited for a time), and the Shamrock. His first book was The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland, published in 1879, which is exactly what it sounds like. This was followed in 1881 by Under the Sunset, a collection of children’s stories, suggesting, as did his voluntary and hobbyist journalism, that there was an imagination in there somewhere, vying with the meticulous bureaucrat.

But it was the meticulous bureaucrat that Irving had wanted, and Stoker took over all his affairs, managing his accounts, his correspondence, the theatre and its staff, advertising, tours (domestic and international), and bookings. The needs of his family, meanwhile, were always subordinate to Irving’s schedule and the requirement that he be forever on call. Being at the head of Irving’s otherwise fluid entourage (it was very easy to fall out of favour), Stoker became an intimate of many of the leading figures of his day, such as Gladstone, Conan Doyle (who admired Stoker’s fiction), W. B. Yeats, George Moore, Sir Richard Burton, David Livingstone, and Alfred Lord Tennyson. Remarkably, Stoker continued to find time to write. His novels were by and large unremarkable, although The Snake’s Pass (1890) reflects a similar creative interest in Irish folklore to the work of his old boss at the Dublin Evening Mail, J.S. Le Fanu.

The workaholic Stoker seemed quite content to live in the shadow of his hero, while theatrical management appealed to both sides of his personality, the administrator and the dreamer. It was a deal more interesting than the minutia of the petty sessions as well. And despite attempts by several biographers and literary theorists to argue otherwise, casting Stoker as variously homosexual, bisexual, asexual, and syphilitic, his marriage to Florence appears to have been just as respectably middle-class and Victorian as the rest of his life. As a gentleman of letters, he was middle of the road but, again, respectable. He wrote for the Daily Telegraph, his novels sold modestly to indifferent reviews, and he could hold his own in a room full of literary lions. And so, his career at the Lyceum rolled respectably along until the night of March 7, 1890, when Stoker had a mother of a nightmare. The dream unsettled him so much that he scrawled the gist of it down on Lyceum notepaper the following day, possibly as a trigger for a story. The setting was a derelict Eastern European castle. ‘Young man goes out,’ he wrote, ‘sees girls one tries to kiss him not on lips but throat. Old count interferes – rage & fury diabolical – this man belongs to me I want him.’ Though he didn’t realise it at the time, he had just begun writing Dracula.

Savvy readers will immediately notice the resemblance of the dream to Jonathan Harker’s most complex, evocative, and erotic journal entry, in which he is seduced by three female vampires in Castle Dracula:

The girl went on her knees, and bent over me, simply gloating. There was a deliberate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive, and as she arched her neck she actually licked her lips like an animal, till I could see in the moonlight the moisture shining on the scarlet lips and on the red tongue as it lapped the white sharp teeth. Lower and lower went her head as the lips went below the range of my mouth and chin and seemed about to fasten on my throat … I closed my eyes in a languorous ecstasy and waited – waited with beating heart.

At this point, ‘as if lapped in a storm of fury’, Dracula appears, sweeps the women aside and declares: ‘How dare you touch him, any of you? How dare you cast eyes on him when I had forbidden it? Back, I tell you all! This man belongs to me!’

It took Stoker the better part of eight years to complete Dracula, which was composed, like his other books, on the fly around his day job; his notes and drafts scrawled on a variety of different notepapers suggesting he wrote on trains, in libraries, hotels, and on family holidays, including a wet week in Whitby where he came across the name ‘Dracula’ in a library book, wrongly believing it was a Romanian word for ‘Devil’. (The fragmentary nature of the novel’s narrative may owe as much to this writing process as to gothic tradition.) ‘Vlad the Impaler’, frequently cited as Stoker’s primary influence for the Count, appears nowhere in Stoker’s meticulous notes. That influence was much closer to home than fifteenth century Wallachia.

The Count and the novel went through many editorial changes right up to publication. Dracula was originally named ‘Count Wampyr’ and was from Styria not Transylvania. The book’s working title was The Un-Dead until it was changed to Dracula at the last minute. Stoker’s nightmare, though, as dramatised in Harker’s journal, was present in every draft. That dream had shocked Stoker, and it stayed with him, gnawing away at all that comfortable Victorian stability. Freud was just beginning to publish when Stoker had this dream and would have most likely gotten a whole chapter out of it. Count Dracula is nothing if not the ‘return of the repressed’. Stoker’s sexuality and his own sense of gender identity seemed in that instant to be at the heart of a battle for control between his Svengali-like employer and the trio of seductive and predatory women, an erotic version of the three witches of MacBeth, one of Irving’s favourite plays. And this was set against a backdrop that was gothic, decadent, and even pornographic. (Stoker would later write an article decrying Fin de siècle erotic novels entitled ‘The Censorship of Fiction’.) As the critic Ludovic Flow wrote of Stoker’s normal literary output: ‘He is a master of the commonplace style in which clichés flow as if they were impelled by the same pressure as genius.’ Flow called this Stoker’s ‘intense command of the mediocre’, but, he concluded, ‘When such a man, just once, is thoroughly afraid, the charade stops and what you get is Dracula.’

Professor Christopher Frayling, meanwhile, has suggested that Stoker’s problem with the nightmare was that he wasn’t scared so much as unsure whether or not he should be enjoying the experience. This can equally be applied to Harker, whose bourgeois and bureaucratic written style in Dracula indicates that he is the character closest to Stoker in outlook and temperament. ‘I felt in my heart a wicked, burning desire that they would kiss me with those red lips,’ writes Harker, adding, ‘It is not good to note this down, lest some day it should meet Mina’s eyes and cause her pain; but it is the truth.’ Given Stoker’s unabashed reverence for Irving, ‘This man belongs to me!’ is also a very loaded statement, implying at once both resentment and, perhaps, desire, as well as the threat that Dracula might be planning to bite him himself…

When the novel was first published in 1897, the year of Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and the exhibition of Philip Burne-Jones’ painting The Vampire, reviewers were similarly perplexed. With all that fluid transfer, clearly there was something strange going on in it, something undoubtedly transgressive and possibly even dirty – though not as much as in the work of Oscar Wilde, who had just been released from prison – but nobody was quite sure what. Contemporary reviews therefore swing between praise and condemnation, often in the same sentence, suggesting that like the gothic discourse itself, reading Dracula produced a profound sense of unease. ‘Dracula is highly sensational,’ ran the Athenaeum review, ‘It reads at times like a mere series of grotesquely incredible events; but there are better moments that show more power … At times Mr Stoker almost succeeds in creating the sense of possibility in impossibility; at others he merely commands an array of crude statements of incredible actions.’ The Athenaeum also argued that the author’s intention was to apparently out gothic the gothic by being deliberately more over-the-top that the novel’s contemporaries (this was the era of Jekyll and Hyde, Dorian Gray, Dr Moreau, and Robert Marsh’s The Beetle, which was published in the same year and outsold Dracula): ‘Mr Stoker is the purveyor of so many strange wares that Dracula reads like a determined effort to go, as it were, “one better” than others in the same field.’ The Manchester Guardian described Dracula as ‘more grotesque than terrifying’, because while ‘it says no little for the author’s powers that in spite of its absurdities the reader can follow the story with interest to the end,’ it remained ‘a mistake to fill a whole volume with horrors’. The Bookman, meanwhile, ‘read nearly the whole thing with rapt attention’ (so not all of it but most of it), while warning: ‘Keep Dracula out of the way of nervous children.’ Neither, according to the Pall Mall Gazette, was it a book for ladies or servants:

Mr. Bram Stoker should have labelled his book ‘For Strong Men Only,’ or words to that effect. Left lying carelessly around, it might get into the hands of your maiden aunt who believes devoutly in the man under the bed, or of the new parlourmaid with unsuspected hysterical tendencies. ‘Dracula’ to such would be manslaughter. It is for the man with a sound conscience and digestion, who can turn out the gas and go to bed without having to look over his shoulder more than half a dozen times as he goes upstairs, or more than mildly wishing that he had a crucifix and some garlic handy to keep the vampires from getting at him.

Dracula, then, was a book for manly men, of the type in fact that the novel repeatedly celebrates. As Van Helsing declares to the American adventurer Quincey Morris: ‘A brave man’s blood is the best thing on this earth when a woman is in trouble. You’re a man and no mistake. Well, the devil may work against us for all he’s worth, but God sends us men when we want them.’

From Stoker’s point of view, his novel was a gothic adventure story in which a few good middle-class men ride out to protect their womenfolk from a foreign devil. It was hi-tech as well, the characters employing shorthand, typewriters, phonographs, telegrams, the theories of Charcot and Lombroso, and Winchester repeating rifles against the forces of darkness, with Quincey Morris representing modernity and the special relationship between the UK and the US. (Stoker had visited America on tour with Irving several times and had just published an adventure set there called The Shoulder of Shasta.) When he sent a complimentary copy of Dracula to William Gladstone, Stoker wrote that there was ‘nothing base in the book’. It was, he conceded, ‘necessarily full of horrors and terrors’, but ‘I trust that these are calculated to cleanse the mind by pity and terror.’ This harks back to Sir Walter Scott’s theory of the gothic, in which the psychological and the cathartic become the function of the text, removing any need for sex or violence. Scott had therefore championed the suspenseful but ultimately rational gothic novels of Ann Radcliffe over the blood and thunder occultism of writers like Matthew ‘Monk’ Lewis. But Stoker was fooling no-one but himself. The constant recourse to the positive power of masculinity in the novel doth, as they say, protest too much. Whether or not he ever acknowledged it to himself, there’s a struggle for Stoker’s soul going on in the text just as much as for Mina Harker’s. And the only way to resolve it was to emphatically destroy the threatening objects of desire – both female and male – in the novel’s climax. As Stoker continued to work with and admire Irving, Dracula must have constituted some sort of emotional breakthrough, though unsurprisingly his fiction took a decidedly dark turn after this which might not have been entirely motivated by commerce. But though The Lady of the Shroud, The Jewel of the Seven Stars, and The Lair of the White Worm are all worth reading, none of them come close to the sheer, page-turning intensity of Dracula.

Author and critics aside, it was Stoker’s mother that immediately grasped the literary significance of Dracula, writing to him enthusiastically that ‘No book since Mrs Shelley’s Frankenstein or indeed any other at all has come near yours in originality, in terror – Poe is nowhere.’ She also predicted that just for once her son might make some money out of his writing, which to a certain extent he did, though Dracula did not originally enjoy the sales of its rivals. For us, it is in every way appropriate to link Dracula to Frankenstein. Both novels equally rule the gothic pantheon, their central characters part of an elite literary group that has transcended the boundaries of the original text and penetrated worldwide popular culture to the extent that they feel more ‘real’ than many historical figures.

Dracula and Frankenstein also share several gothic motifs and devices. Both are fragmented texts, with different narrators telling different parts of the story, offering alternative and subjective points of view. In the gothic, this destabilises narrative cohesion in opposition to the ‘God’s eye view’ of the single perspective of the realist novel. Stoker’s heroes also keep a record to share with each other and to protect themselves against the possible legal ramifications of opening graves, mutilating corpses, and murdering foreign aristocrats. He was therefore probably influenced more by Wilkie Collins than by Mary Shelley or Robert Maturin’s even more structurally unstable Melmoth the Wanderer (another Anglo-Irish gothic novel). In The Woman in White, Collins had begun the novel by explaining that the story was to be told by each main character ‘from their own knowledge’, just as ‘the story of an offence against the laws is told in Court by more than one witness’. Both novels also explore gender identity and the threat of the monstrous in forms that have become genre archetypes. The ‘Frankenstein archetype’ represents threats from within, Victor Frankenstein’s blasphemous ambition and, ultimately, madness birthing his creation – as Dr Jekyll later would Mr Hyde – while the ‘Dracula archetype’ is one of external threat invading the individual like a virus, such as vampirism or the zombie hoards unleashed on film and fiction after George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. In both stories, male protagonists miserably fail to protect their wives from monsters, and there is a common dread that humanity could ultimately be overrun by unholy creatures. In Dracula, Van Helsing fears the Count will reign as ‘the father or furtherer of a new order of beings, whose road must lead through Death, not Life.’ In Frankenstein, Victor destroys the Eve he has been coerced into making for his creature so that his race, which is physically superior to mere mortals, cannot propagate.

Count Dracula is not, however, the first vampire to appear in literature, though it is undisputedly him to which the crown will always belong. This may be because of the age in which he first appeared, the novel riven with the anxieties of the British Empire at the Fin de siècle, of the dangers of immigration and invasion, decadence and moral decline, new women, and the ravages of syphilis. Though hugely popular in its own day, John Polidori’s 1819 story ‘The Vampyre’ just didn’t hit the same cultural nerve, its mystique bound up much more with the resemblance of the story’s antagonist, ‘Lord Ruthven’, to Polidori’s former employer Lord Byron, another uneasy ‘master/slave’ relationship like that of Stoker and Irving. Ruthven is most significant in moving the image of the vampire away from the grotesque revenant of European folklore to that of the urbane and attractive aristocrat. It is also worth remembering Robert Southey’s epic poem Thabala the Destroyer (1800), because of the similarities in its Eighth Book to the undeath/true death of Ellen Terry lookalike Lucy Westenra in Dracula:

‘This is not she!’ the Old Man exclaimed,

‘A Fiend! a manifest Fiend!’

And to the youth he held his lance,

‘Strike and deliver thyself!’

Oddly, before this, the vampire – a myth born out of the Black Death – had not featured in eighteenth century gothic fiction, which was more concerned with ghosts, demons, mad monks, and murderous medieval lords. Other than the fireside tales of superstitious peasants, vampires were the preserve of philosophers, theologians, and medical men, their attributes documented terribly seriously in works like John Heinrich Zopfius’ Dissertatio de Vampiris Seruiensibus (1733), and Dom Augustine Calmet’s Traité sur les Apparitions des Espirits, et sur les Vampires (1746).

Carmilla

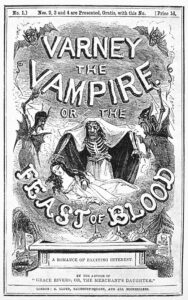

Varney The Vampire

The next significant literary bloodsucker sprang from the penny dreadfuls. Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood was published by the king of the ‘penny bloods’ Edward Lloyd between 1845 and 1847. It was written by James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, prolific penny-a-liners who were also behind Lloyd’s other huge hit, The String of Pearls: A Domestic Romance (1846-47), which loosed Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, upon the world. Cursed with vampirism after he betrayed a royalist to Oliver Cromwell, the morally ambivalent Sir Francis Varney wanders through history having adventures until he finally leaves his written confession with a priest and hurls himself into Mount Vesuvius. Varney the Vampire introduced many of the vampire tropes we nowadays take for granted, but largely by stealth as its status as a cheap illustrated serial for a predominantly working-class audience kept it a long way outside the Victorian literary canon.

Before Dracula, the last significant vampire story was ‘Carmilla’ by Stoker’s fellow-Irishman Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, the owner of the Dublin Evening Mail when Stoker was its theatre critic. ‘Carmilla’ is one of his ‘psychic detective’ Dr Martin Hesselius’ supernatural case studies from the collection In A Glass Darkly (1872). An elderly woman, Laura, recalls summer in her youth in Styria when a mysterious young woman came to stay at the family castle. Carmilla is the perfect companion, charming, affectionate, and beautiful, though her designs on Laura seem to go beyond mere friendship:

Sometimes after an hour of apathy, my strange and beautiful companion would take my hand and hold it with a fond pressure, renewed again and again; blushing softly, gazing in my face with languid and burning eyes, and breathing so fast that her dress rose and fell with the tumultuous respiration. It was like the ardor of a lover; it embarrassed me; it was hateful and yet over-powering; and with gloating eyes she drew me to her, and her hot lips travelled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, ‘You are mine, you shall be mine, you and I are one for ever.’ Then she had thrown herself back in her chair, with her small hands over her eyes, leaving me trembling.

Young women in the nearby village, meanwhile, are dying of a mysterious illness while Laura dreams at night of being visited by an enormous black cat. The story recalls Coleridge’s incomplete poem Christabel (1800), and the relationship between Christabel, a young woman of noble birth, and the mysterious Geraldine, who bears the mark of the vampire:

Beneath the lamp the lady bowed,

And slowly rolled her eyes around

Then drawing in her breath aloud,

Like one that shuddered, she unbound

The cincture from beneath her breast:

Her silken robe, and inner vest,

Dropt to her feet, and full in view,

Behold! her bosom and half her side –

A sight to dream of, not to tell!

O shield her! shield sweet Christabel!

The similarities between ‘Carmilla’ and Dracula are striking, and it seems unlikely that Stoker was not influenced by his former employer’s story. The name of Dracula’s insane familiar, ‘R.M. Renfield’, echoes Bertha Rheinfeldt, another of Carmilla’s victims, and both stories have elaborate framing narratives and feature rich and sexually magnetic antagonists posing as descendants of themselves. Carmilla and Count Dracula target female heroines, and each can transform into animals and pass through locked windows and doors. Le Fanu’s eccentric vampire hunter Baron Vordenburg is a lot like Van Helsing, and their method of killing vampires is the same, as are the described symptoms of vampirism. The original opening chapter of Dracula, cut from the final draft and published separately as the short story ‘Dracula’s Guest’, features a female vampire called Countess Dolingen von Gratz, and is also set in Styria. (In the story, Harker is saved through the intervention of Dracula.) Both texts are also, of course, oozing with transgressive sexuality. Forbidden desire is at once compelling and appalling, a tension at the heart of the stories and the society that produced them that is never resolved in either fiction or fact. As Michel Foucault wrote of the Victorians in his History of Sexuality:

Sexuality was carefully confined; it moved into the home. The conjugal family took custody of it and absorbed it into the serious function of reproduction. On the subject of sex, silence became the rule. The legitimate and procreative couple laid down the law. The couple imposed itself as model, enforced the norm, safeguarded the truth, and reserved the right to speak while retaining the principle of secrecy. A single locus of sexuality was acknowledged in social space as well as at the heart of every household, but it was a utilitarian and fertile one: the parents’ bedroom. The rest had only to remain vague; proper demeanour avoided contact with other bodies, and verbal decency sanitized one’s speech. And sterile behaviour carried the taint of abnormality; if it insisted on making itself too visible, it would be designated accordingly and would have to pay the penalty.

Foucault called this the ‘monotonous nights of the Victorian bourgeoisie’. Perfectly healthy drives therefore become taboos to be allegorised in sensational fiction and then well and truly contained. Lucy Westenra, for example, who plays her three suitors off against one another and laments ‘Why can’t they let a girl marry three men, or as many as want her, and save all this trouble?’ certainly pays the price after the vampire’s bite fully sexualises her: staked through the heart, decapitated, and her mouth stuffed with garlic by a group of men who are all doing this for the ‘good of her soul’. (Le Fanu’s Carmilla had similarly been staked, decapitated, and then burnt.) Never in Victorian literature were ‘new women’ so emphatically silenced.

Desire, sex, and women certainly made Stoker uneasy, as they did the majority of his class and gender in late Victorian England. This can be seen in his article on the needful censorship of erotic fiction, in which he tellingly writes: ‘A close analysis will show that the only emotions which in the long run harm are those arising from sex impulses, and when we have realized this we have put a finger on the actual point of danger.’ Yet to suggest that this anxiety was worked out through the creation and destruction of female vampires would be too easy. It is a vital first step in understanding Dracula, but not the thing in itself. That men are scared of women is not a surprise, especially Victorian men. Equally, it is not only patriarchal authority that the novel seeks to reassert, but Christian values. As Foucault also argued, historically Christian discourse has always linked sexual desire to what Milton called ‘Man’s first disobedience’ in the Garden of Eden, an evil consequence of Eve seduced by the serpent. By the end of the century, fears of the British Empire sapped of its strength by decadence and evolutionary ‘degeneration’ abounded among the political and intellectual elite, with Christian certainty knocked by modernity and soon to be blown apart on the Western Front. Though notionally presented as a scientist in a world of technological marvels, Van Helsing falls back more and more on the weapons of both religion and superstition during his pursuit of Dracula: garlic flowers, the bible, the host, and the crucifix, the trappings, in fact, of the Old Faith, Catholicism, over English Protestantism. Perhaps he is driven to idolatry in battling an ancient force from the East, or perhaps Stoker sees the need for the Church to find its original strength through returning to source, pre-Reformation. Given the influence of the Oxford Movement, he would hardly have been alone in such views. Otherwise, as explored around the same time in the ambivalent Imperial Gothic of Rudyard Kipling, there are places in the world where, even if you do not believe, even if it cannot possibly be true, it is the old ways that work against supernatural evil, not the new.

In the end, despite all those blood transfusions and Van Helsing’s scientific mysticism, it is Mina Harker’s ‘unclean’ psychic connection to the Count that facilitates his defeat. And when Harker in the novel’s denouement talks of his and Mina’s hope that some of Quincey’s ‘brave spirit has passed into’ their son, he conveniently forgets that after his wife’s ‘baptism of blood’ (when she drinks from a wound in Dracula’s chest in the most extreme scene in a novel of extremes), that there must be some of the Count’s ‘spirit’ in their child too, as well as still in his wife and, indeed, in Stoker. It’s highly unlikely that he ever truly laid that particular demon. Either way, this was not entirely the win the menfolk probably intended, and Stoker must have realised that as well. There is too much sexual and, indeed, moral and religious ambiguity in the text to be so easily concluded, and it is no accident, I suspect, that the campaign against Dracula is planned within the walls of Dr Seward’s asylum. Sex and Death and Madness always go hand in hand in Dracula.

And all this still leaves a deeper layer yet. It is obvious from Stoker’s nightmare and all the way through the novel that Dracula is Irving, not the devil, and not Vlad III. They look identical, they employ similarly melodramatic patterns of speech, and their imperious, controlling, forceful, and destructive personalities are just as in tune as their looks. Harker, pulled away from his wife by Dracula, is Stoker under Irving’s yoke until, as his son Noel later wrote, the actor ‘wore Bram out’ and his health quickly failed, just as the Count drained the lifeforce from his victims. Ellen Terry, meanwhile, Irving’s leading lady, also bore more than a passing resemblance to the free spirited, sexy, and doomed Lucy. How, I wonder, did they feel, to see themselves in Stoker’s novel (if they recognised themselves at all), stabbed through the heart and dismembered? We have only one record of Irving commenting on Dracula. To safeguard copyright on future theatrical versions of the novel, Stoker hastily converted it to a four act play that was read on stage at the Lyceum in front of an audience of family friends, staff, and a few regulars. Irving deigned to attend, and after the performance Stoker asked him what he thought. ‘Dreadful!’ replied Irving, adding nothing more on the subject. So vast was his ego, he may never even have realised that the song was about him.

But it is Dracula not Irving that lives on in the public memory, and always will. As long as there are folk on earth reading books and watching movies, Dracula will endure. Like Frankenstein it has touched something very deep in the human psyche. Perhaps it is because vampires are attractive. I think we can agree that nobody really wants to be a reanimated corpse or a human fly, or for that matter an evil ghost, demonically possessed, or criminally insane. But what Dracula offers… well, that might be worth considering: eternal life, eternal youth, superior strength, resistance to disease, animal magnetism, and magical powers, all for the price of a bit of blood. That might be a little harder to turn down.

Or perhaps the reason’s more mundane. When Carl Laemmle optioned Dracula for Universal in 1930, studio lawyers discovered that Stoker had incorrectly filed for US copyright and the book was in fact in the public domain. This has meant that filmmakers have been free to adapt the story ever since, resulting in well over 200 movies and counting, the character crowding out every other bloodsucker in the field. And the best of these films are, of course, iconic, the name ‘Dracula’ synonymous to this day with his portrayals by Max Schreck, Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee, and Gary Oldman, although none of the movies – not even in the promised authenticity of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula – ever faithfully reproduce the original story as written by Stoker. The novel is then further complicated by a legion of academic interpretations, reflecting the shifting sands of literary theory across the decades. There are Freudian analyses, Jungian, Lacanian, Marxist; feminist readings, antifeminist readings, and queer theories; it is colonial, post-colonial, and anti-colonial; modernist, postmodernist, and a whole bunch of other things besides, many if not all of which would have probably appalled Stoker.

It is thus these days quite difficult to get back to the character as created by his author, but to revisit this remarkable and complex novel is well worth the commitment. When I picked it up again, after a thirty-year break since I read it at a student, very quickly I could not put it down. There’s an energy to the prose that sweeps you up and carries you along, like the heroine of an old Expressionist movie, in the arms of a shadowy figure disappearing across the rooftops towards a sublime castle. And who doesn’t want that? Simply surrender and see where the Count takes you. Ignore the academics, forget the films, and make your own minds up about Stoker’s vision: ‘Listen to them – the children of the night. What music they make!’

Main image: Whitby Abbey, Yorkshire, England, lit by the evening sun. Credit: Brian Maudsley / Alamy Stock Photo

Images in text:

Sir Henry Irving as Hamlet, at the Lyceum Theatre. London 1874 Credit: Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

Wrapper of the first number of Thomas Pecket Prest’s ‘Varney the Vampire,’ published in London in 1853. Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Illustration by David Henry Friston for ‘Carmilla’, in The Dark Blue (February 1872), electrotype after wood engraving, reproduced in Best Ghost Stories, 1872. Credit: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo