Vampire: Blood is the Life – Part Two

David Stuart Davies concludes in a similar vein.

Part Two: Dracula & Beyond

Bram Stoker (1847 – 1912) was influenced by Le Fanu’s Carmilla when he came to write his vampire masterpiece Dracula (1897), particularly in his treatment of the trio of female vampires who attack Jonathan Harker during his stay at Castle Dracula. Similarly, Le Fanu’s vampire expert, Baron Vodenburg, can be seen as a forerunner of Stoker’s Professor Van Helsing.

Stoker laboured almost seven years on the novel, researching European folklore and vampire tales from around the world. His visits to Whitby were influential and he incorporated a real shipwreck that occurred there in the novel. The Dead Un-Dead was one of Stoker’s original titles for Dracula and, up until a few weeks before publication, the manuscript was titled simply The Un-Dead. Stoker’s notes reveal that the name of his vampire was originally ‘Count Wampyr’, but while doing research, Stoker came across an intriguing name; ‘Dracula’, meaning ‘Son of the Order of the Dragon.’ This name belonged to a real fifteenth-century nobleman, Prince Vlad Dracula, also known as Vlad the Impaler because of his harsh and cruel treatment of his enemies. Stoker took the name for his aristocratic bogeyman.

In writing the novel, Stoker added to the vampire lore by creating new rules, including the concept of the vampire needing to lie in a coffin which contained a layer of his native soil during the daylight hours, requiring an invitation to enter a building and casting no reflection in a mirror. These rules have been adhered to in countless stories and movies.

At the heart of the book, like a hypnotic dark fire, stands the figure of Count Dracula, a tall, lean mesmeric character who, it has been suggested, exhibited the same gaunt appearance and commanding presence as the actor Henry Irving. Stoker was Irving’s manager and the author hoped that he would play Dracula in a stage version of the story but the actor disliked the work intently.

Much of the novel’s immediate success was due to Stoker’s innovative use of a contemporary setting. Readers were able to identify with the modern English scene, which provides the backdrop for the bulk of the narrative, and which is contrasted wonderfully with the gothic aura infused into the early section of the novel set in the wilds of Transylvania. But the greatest element of this fascinating book is of course the Count himself. Dracula is a violent, vile villain and a tragic creature trapped by his own damned condition. He is both a frightening but also disturbingly attractive character whose vampiric life very quickly assumed mythic status in popular culture, which is the key to his everlasting appeal.

Dracula was published towards the end of the nineteenth century and was a phenomenal success. It is interesting to note that few vampire novels were published for quite some time afterwards. It was as though writers realised that they could not top this masterpiece.

However there were some excellent short stories penned around the same time and into the early twentieth century featuring a range of bloodsuckers, most significantly Guy de Maupassant’s ‘The Horla’, F. Marion Crawford’s ‘For the Blood is the Life’, M. R. James’ ‘An Episode of Cathedral History’ and Edith Wharton’s ‘Bewitched’.

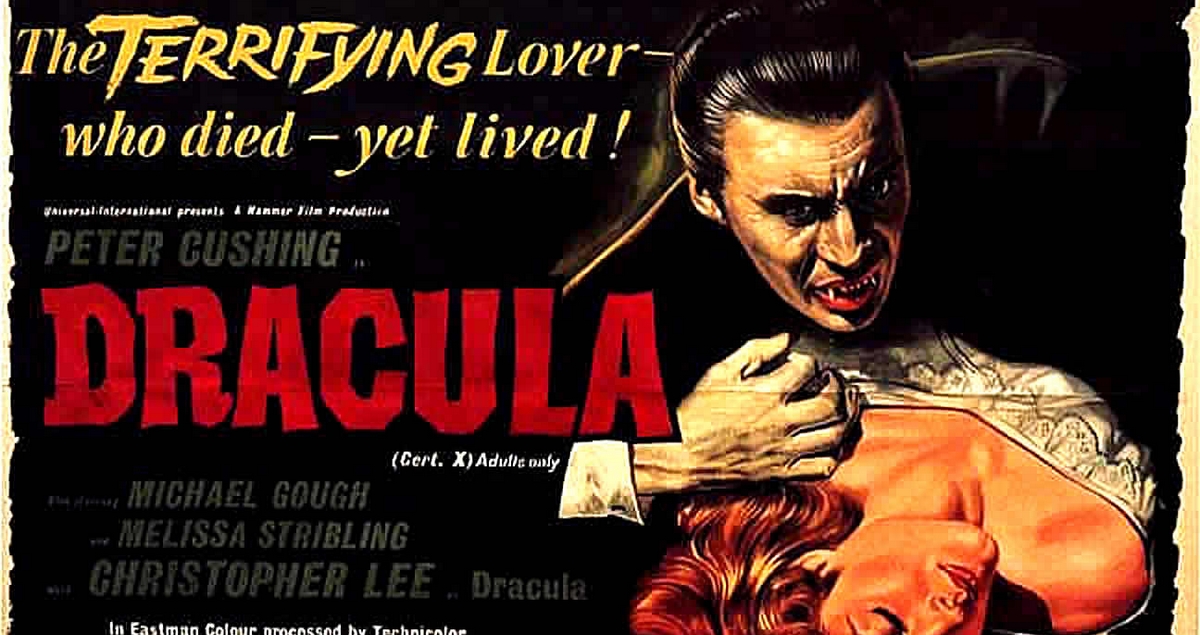

Dracula gained a second lease of life when Hollywood took hold of the text. Bela Lugosi starred in the 1931 movie version of Stoker’s novel and he became the visual representation of the arch vampire for a generation. The film spawned countless other Dracula and vampire movies and Lugosi was indelibly linked to the character for the rest of his life, finally spreading his bat wings to frighten the likes of Abbott and Costello and Mother Riley. For the best part of the twentieth century, the vampire flourished on the cinema screen: after the run of bloodsucker shockers from Hollywood in the thirties and forties, Hammer films in Britain took up the baton in the fifties, giving us a new tall, handsome and sexy Dracula in the shape of Christopher Lee who, in the end, made far more of these movies than he should have.

It was in the 1970s that there came a revival of interest in the vampire novel. One of the influential books at this time was Salem’s Lot (1975) by Stephen King. He was inspired by Dracula: ‘One night over supper I wondered aloud what would happen if Dracula came back in the twentieth century, to America. If he were to show up in a sleepy little country town, what then? I decided I wanted to find out, so I wrote Salem’s Lot, which was originally titled Second Coming.’ This book prompted other writers to jump on board the vampire bandwagon, including Anne Rice with her 1976 novel, Interview with a Vampire. This bestseller features Louis de Pointe du Lac, who tells the story of his life to a reporter. In 1791, Louis is a young indigo plantation owner living south of New Orleans. Distraught by the death of his brother, he seeks death in any way possible. Louis is approached by a vampire named Lestat de Lioncourt, who desires his company. Lestat turns Louis into a vampire and the two become immortal companions. The novel was followed by a large number of widely popular sequels, collectively known as The Vampire Chronicles. A film adaptation of the original novel was released in 1994, starring Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise.

Today vampire fiction remains in healthy shape. For evidence consider the very successful Twilight series by Stephanie Meyer and the novels of Charlaine Harris. The fascination with these dark children of the night continues partly, I believe because even the most rational of us can harbour a faint belief that these creatures really do exist.

Books associated with this article

Dracula

Bram Stoker

Dracula & Dracula’s Guest

Bram Stoker

Dracula (Collector’s Edition)

Bram Stoker