The Rise of the Gothic Novel

‘It was a question of suspense versus horror’. Stephen Carver compares the works of the two giants of English Gothic literature, Ann Radcliffe and Matthew ‘Monk’ Lewis.

During the Renaissance, ‘gothic’ was a label for all things barbarous. To European Humanist intellectuals, there were two epochs of cultural excellence in human history: the Classical and their own. These were separated by a terrible period of ignorance and brutality – the Dark and Middle Ages – brought about by the Goths, the Germanic tribes that had brought down the Roman Empire. François Rabelais first applied the term to literature in the sixteenth century, meaning anything that failed to reflect Classical ideals and scholarship, and which was therefore vulgar. When Horace Walpole appended ‘A gothic story’ to the title of his influential 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto (referring to its medieval setting) – a tale of intrigue and murder prefaced by an ominous prophecy – the gothic romance was effectively born.

Originally presented as the translation of a sixteenth-century Italian manuscript, Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford and a Whig MP, explained his project in a preface to the second edition, writing that ‘It was an attempt to blend the two kinds of romance, the ancient and the modern. In the former all was imagination and improbability: in the latter, nature is always intended to be, and sometimes has been, copied with success’ (Walpole: 1984, 43). This synergy of naturalism and romance signalled a current debate in the literature as to whether the relatively new art of prose fiction should reflect real life or the imagination. The Castle of Otranto was followed by The Old English Baron by Clara Reeve in 1778, which the author described as ‘the literary offspring of The Castle of Otranto’ in a preface (Reeve: 1883, iii).

Influenced by Voltaire, the next notable English gothic novel was originally written in French. Vathek was a bit of fun by the art collector William Beckford, penned in 1782 (when he was twenty-one) and translated by the clergyman Samuel Henley in 1786 as An Arabian Tale, From an Unpublished Manuscript. Reflecting the then fashion for Orientalism in art and design, Vathek eschewed the medieval settings of Walpole and Reeve and was instead set in the eighth century Abbasid Caliphate. In the novel, the Caliph Vathek renounces Islam and embarks on an occult path of violence and debauchery – often in the company of his mother – intended to gain his mystical powers. Vathek and his entourage eventually arrive at the Halls of Eblis, the Islamic hell, but for attempting to transgress the boundaries of human knowledge prescribed by God, they are damned to wander the halls endlessly and silently, their hearts burning with eternal fire. The gothic novel had arrived, with wild settings, sexually magnetic antiheroes and supernatural (or apparently supernatural) events intended to evoke a sublime terror in its readers, perfectly suiting the rebellious sensibility of late-eighteenth-century Romanticism.

With its preoccupation with physical violence and extreme emotional states – obsession, anxiety, paranoia, guilt and fear – gothic fiction allowed for the exploration of the dark, irrational and extreme elements of thought and experience. As Rosemary Jackson wrote, ‘It is all that is not said, all that is unsayable, through realistic forms’ (Jackson: 1981, 26). Sometimes these stories allowed for a natural explanation, a happy ending even, and sometimes they did not. The form thus reflected the anxieties and vulnerabilities of a culture in upheaval, as well as the hope – the English still reeling from the American and French Revolutions and coming to terms with industrialisation. Epistemological paradigms, therefore, collided in gothic fiction, with the old worldview of the superstitious (Catholic, European) Middle Ages – where and when the majority of the stories were set – appearing to haunt Enlightenment (Protestant, English) reason. This is why gothic fiction is fascinated by doppelgängers and nightmares, of Self versus Other and monsters from the id. The archaic setting at once contained the barbarous past and reminded readers that it was not so far away or, worse, still carried inside; not dead but sleepeth. The fragile trappings of the so-called civilised world, therefore, offered little protection, despite the protestations of Henry Tilney in Austen’s satire of the gothic novel, Northanger Abbey: ‘Remember the country and the age in which we live. Remember that we are English, that we are Christians’ (Austen: 1988, 199).

The two primary exponents of gothic fiction in England were Ann Radcliffe (1764 – 1823) and Matthew ‘Monk’ Lewis (1775 – 1818). Their work was at once similar and totally different, and these divergent approaches illustrate the conceptual split in the gothic as a literary genre. In short, it was a question of suspense versus horror.

Not being blessed with children, Mrs Radcliffe, the wife of the journalist William Radcliffe, wrote to pass the time as much as to supplement the household income, authorship then being one of the only respectable ways a middle-class woman could earn a living. Set in a sublime landscape of ruined castles and wild coastlines, her first novel, The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne: A Highland Story (1789), is a tale of clan feuds and romantic intrigues pre-dating Walter Scott’s early border ballads by over twenty years and which was probably influenced by Reeve. This was followed by A Sicilian Romance in 1790, a tale of fallen nobility related to a tourist by a monk in a ruined castle, and The Romance of the Forest in 1791. The latter explored the tension in the human psyche between hedonism and morality, anticipating Freud by a century. This was a hit, establishing its author’s reputation through its sophisticated realisation of the gothic devices of the earlier novels: persecuted heroines, brooding villains, remote settings, seemingly supernatural events and cliff-hanging chapter endings.

Mrs Radcliffe’s next work was The Mysteries of Udolpho in 1794, a quintessential gothic romance that earned her £500 from her publisher, G. G. and J. Robinson (the equivalent of nearly £40,000 today). Set in the late-sixteenth century, the novel concerns the perils of Emily St. Aubert, a young French orphan compelled to move to the remote Castle Udolpho in Northern Italy when her aunt and guardian, Madame Cheron, marries the sinister Signor Montoni. After her aunt dies under suspicious circumstances, Emily’s life, fortune and honour are threatened by the villainous Montoni, who imprisons her in the labyrinthine and apparently haunted castle from which she must escape…

Radcliffe’s technique is epitomised by the ‘black veil’. This is a recurring motif in the novel that generally heralds the glimpse of an apparent apparition, and a symbol for that which is hidden, terrifying and perversely compelling:

Emily passed on with faltering steps, and having paused a moment at the door before she attempted to open it, she then hastily entered the chamber and went towards the picture, which appeared to be enclosed in a frame of uncommon size, that hung in a dark part of the room. She paused again, and then, with a timid hand, lifted the veil; but instantly let it fall — perceiving that what it had concealed was no picture, and, before she could leave the chamber, she dropped senseless on the floor (Radcliffe: 1970, 248-249).

The black veil fascinates and appals Emily throughout the story. Radcliffe uses it to tease the reader, building suspense while the dusky pall conceals imagined horrors with all the conviction of a negligee. Only in denouement is the shocking but mysterious vision explained:

It may be remembered, that, in a chamber of Udolpho, hung a black veil, whose singular situation had excited Emily’s curiosity, and which afterwards disclosed an object, that had overwhelmed her with horror; for, on lifting it, there appeared, instead of the picture she had expected, within a recess of the wall, a human figure of ghastly paleness, stretched at its length, and dressed in the habiliments of the grave. What added to the horror of the spectacle, was, that the face appeared partly decayed and disfigured by worms, which were visible on the features and hands. On such an object, it will be readily believed, that no person could endure looking twice … Had she dared to look again, her delusion and her fears would have vanished together, and she would have perceived, that the figure before her was not human, but formed of wax (Radcliffe: 1970, 662-663).

After the wild ride comes to the reassurance. The reason is restored following the vicarious thrill of the horror story – all that sexual threat, violence and paranormal activity. There are no real monsters lurking in the dark after all. The effectiveness is cathartic while containing any dangerous fantasies. The apparently subversive anti-novel is therefore an agent of social and psychological control, allowing the readers to safely let off a little steam.

In the Radcliffian gothic paradigm, the emotional experience was everything, while the supernatural was ultimately discarded. As Walter Scott later wrote of her, ‘A principal characteristic of Mrs Radcliffe’s romances, is the rule which the author imposed upon herself, that all the circumstances of her narrative, however mysterious, and apparently superhuman, were to be accounted for on natural principles, at the winding up of the story’ (Scott: 1824, xxiv). This was a continuation of his theory of the gothic as posited in his review of Frankenstein for Blackwood’s:

the author’s principal object … is less to produce an effect by means of the marvels of the narrations, than to open new trains and channels of thought, by placing men in supposed situations of an extraordinary and preternatural character, and then describing the mode of feeling and conduct which they are most likely to adopt. (Scott: 1818, 613).

The reference to ‘supposed situations’ signals the final removal of the fantastic from the gothic discourse as far as Scott was concerned, hence his admiration for Radcliffe over other writers of supernatural horror. Echoing Henry Tilney, he went on to apply this to reports of supposedly ‘real’ hauntings and apparitions, then routinely reported in the popular press, all of which he debunked in his Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft (1830). ‘Even Sir Walter Scott is turned renegade’, James Hogg complained in Blackwood’s, as ‘a great number of people nowadays are beginning broadly to insinuate that there are no such things as ghosts’ (Hogg: 1830, 943).

Ghosts, however, there were aplenty in Matthew Gregory Lewis’ response to The Mysteries of Udolpho. While Mrs Radcliffe had, as Ian Duncan has written, elevated anxiety to a ‘metaphysical state’, Lewis’ novel The Monk: A Romance published in 1796 – another seismic literary event – relied on horror and sensationalism, letting occult and supernatural elements stand without explanation or rationalisation (Duncan: 1992, 47). He was, nonetheless, by his own admission, hugely influenced by the already successful Radcliffe.

The story is one of temptation and fall, born out of the repression of religious abstinence. Ambrosio, a young friar known for his devotion, is attracted to Matilda, a girl he’s used as a model to paint the Virgin Mary. Disguised as a boy, Matilda enters Ambrosio’s monastery as a novice and seduces him. Once initiated into the sins of the flesh, Ambrosio’s lust increases. He quickly tires of his lover and ingratiates himself into the home of Lady Elvira in pursuit of her daughter, Antonia, aided by Matilda, who convinces him to use black magic to achieve his goals, culminating in a demonic pact. Things do not end well for anyone, leading to a dark and visceral climax which still makes for quite shocking reading today. The Monk is further enlivened by a lengthy subplot in which a young woman called Agnes is delivered into the hands of an evil prioress by Ambrosio after she confesses she is pregnant by her lover, Raymond, who her mother also desires. Agnes must face the horrors of the Inquisition while Raymond must outwit the ‘Ghost of the Bleeding Nun’…

For those that knew him, Matthew Lewis was an unlikely candidate to produce the Georgian equivalent of The Exorcist. Educated at Westminster and Oxford, Lewis was sent to Europe to perfect his French and German in order to follow his father into the diplomatic service. He married Frances Maria Sewell, a popular woman at court, and entered Parliament, quickly rising to the position of Deputy-Secretary at War. As a young man in Europe, Lewis was particularly inspired by German literature, including the Schauerroman (‘shudder novel’) which, like the French roman noir, was concurrently developing with the English gothic, and was much more violent. An able translator, he introduced some key German Romantic writers to England, including Goethe and Schiller. Bored by a job at the British Embassy in The Hague, the twenty-year-old Lewis wrote Ambrosio (The Monk) in ten weeks in an attempt to emulate Walpole, publishing anonymously. The first edition sold well and a second followed at the end of the year, this time bearing Lewis’ name and his rank, now MP.

The book’s reception was electric. Coleridge declared it ‘the offspring of no common genius’ in the influential Critical Review, but his praise came with the warning that ‘if a parent saw in the hands of a son or daughter, he might reasonably turn pale’. This was because ‘Tales of enchantments and witchcraft can never be useful’ but ‘our author has contrived to make them pernicious, by blending, with an irreverent negligence, all that is most awfully true in religion with all that is most ridiculously absurd in superstition’. The Monk was, in short, said Coleridge, ‘a mormo for children, a poison for youth, and a provocative for the debauchee’. (A ‘Mormo’ or ‘Mormon’ was a spirit in Greek mythology – usually depicted as female – and a ‘bogey’ invoked by parents to frighten children into good behaviour.) Worse, ‘the author of the Monk signs himself a LEGISLATOR! We stare and tremble’ (Coleridge: 1797, 197-198). Similarly, in his poem, The Pursuits of Literature, the Italian scholar Thomas James Mathias suggested that a passage in which Ambrosio and Elvira discuss the Bible in less than glowing terms made the novel indictable under the law for blasphemy. The Marquis de Sade, meanwhile, praised the novel as foremost among ‘these new novels in which sorcery and phantasmagoria constitute the entire merit’, pronouncing it ‘superior in all respects to the strange flights of Mrs Radcliffe’s brilliant imagination’ and ‘the inevitable result of the revolutionary shocks which all Europe has suffered’ (Sade: 1991, 108-109). As the debate continued, with Lewis’ publisher Joseph Bell weighing in against his detractors with a published ‘Vindication’, the book went through five editions and continued to sell like eel pies at a hanging. As Lewis’ biographer, Louis Peck has written, the reading public ‘had been told that the book was horrible, blasphemous, and lewd, and they rushed to put their morality to the test’ (Peck: 1961, 28).

Mrs Radcliffe certainly saw The Monk as a challenge to her literary status and the genre she had refined, if not effectively created, in its modern form. Her answer was The Italian, published a year after The Monk. The Italian explored many of the same dark human drives as The Monk but in a much more indirect and subtle way. Like Lewis’ novel, the antagonist of The Italian is a dangerous and Machiavellian monk, Father Schedoni, whose portrayal is considered by critics old and new to be the dramatic heart of the narrative. Unlike Lewis, Radcliffe showed how depravity does not need to be infernally inspired and is, in fact, a very human trait, while equally that the lust for power is just as potent and dangerous as unbridled sexual desire.

The Italian was to be Radcliffe’s last published novel in her lifetime, although the inferior Gaston de Blondeville was released by Henry Colburn three years after her death. Radcliffe was a very private woman, and why she chose to stop writing at the height of her fame remains a mystery. It may be that the mixed reviews of The Italian left her demoralised or that she was discouraged by the increasing fashion for graphic horror over sublime suspense in the genre. She and her husband used the money she had made from writing to travel extensively until she died of pneumonia in 1823, aged 58.

Matthew Lewis died in 1818, the year Frankenstein was published. He had been visiting his estates in Jamaica and succumbed to yellow fever during the voyage home. He had met Mary Shelley and her husband two years before in Geneva and had told them five ghost stories which Percy recorded in his journal. He had continued to write lurid gothic tales, the most successful of which was the play The Castle Spectre, first performed in 1797, although his later work was dogged by accusations of plagiarism.

Lewis’ immediate critical legacy as a weak and sensational writer was in stark contrast to the posthumous reputation of the ‘Mistress of Romance’. Radcliffe was admired and cited as an influence by not only Scott but Poe, Balzac, Hugo, Dumas and Baudelaire, while her equivalent in cinema is almost certainly Hitchcock. Lewis’s reputation as a master of horror took longer to recover, although The Monk was never out of print. In modern gothic studies, however, it is unthinkable to cite Radcliffe without a comparison with Lewis. They are both sides of the same coin, a matched pair. And like the devil, there’s a little bit of The Monk in every horror story and film that ever embraced shock over suspense, and didn’t shy away from sex and violence. Hammer Films, EC Comics, Stephen King and George A. Romero would all be unthinkable without The Monk, and you can judge any scholar of the genre by what they have to say about both these Georgian pioneers of gothic fiction.

WORKS CITED

Austen, Jane. (1988). Northanger Abbey. London: Penguin. (Original work published 1818).

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. (1797). ‘The Monk: A Romance. By M.G. Lewis, Esq. M.P.’. Critical Review XIX (February).

Duncan, Ian. (1992). Modern Romance and Transformations of the Novel: The Gothic, Scott, Dickens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hogg, James. (1830). ‘The Mysterious Bride’. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, XXVIII (174), (December).

Jackson, Rosemary. (1981). Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. London: Routledge.

Lewis, Matthew. (1990). The Monk: A Romance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1796).

Peck, Louis (1961). A Life of Matthew G. Lewis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Radcliffe, Ann. (1970). The Mysteries of Udolpho: A Romance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1794).

Reeve, Clara. (1883). The Old English Baron. London: J.C. Nimmo and Bain. (Original work published 1778).

Sade, Donatien Alphonse François de. (1991). ‘Reflections on the Novel’. The 120 Days of Sodom and Other Writings. Austryn Wainhouse and Richard Seaver trans. London: Arrow. (Original work published 1800.)

Scott, Walter. (1818). ‘Remarks on Frankenstein; or the Modern Prometheus, 1818’. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine I (2), (March).

Scott, Walter. (1824). ‘Prefatory Memoir of the Life of the Author’. The Novels of Mrs. Anne Radcliffe. London: Hurst, Robinson & Co.

Walpole, Horace. (1984). The Castle of Otranto. London: Penguin. (Original work published 1764).

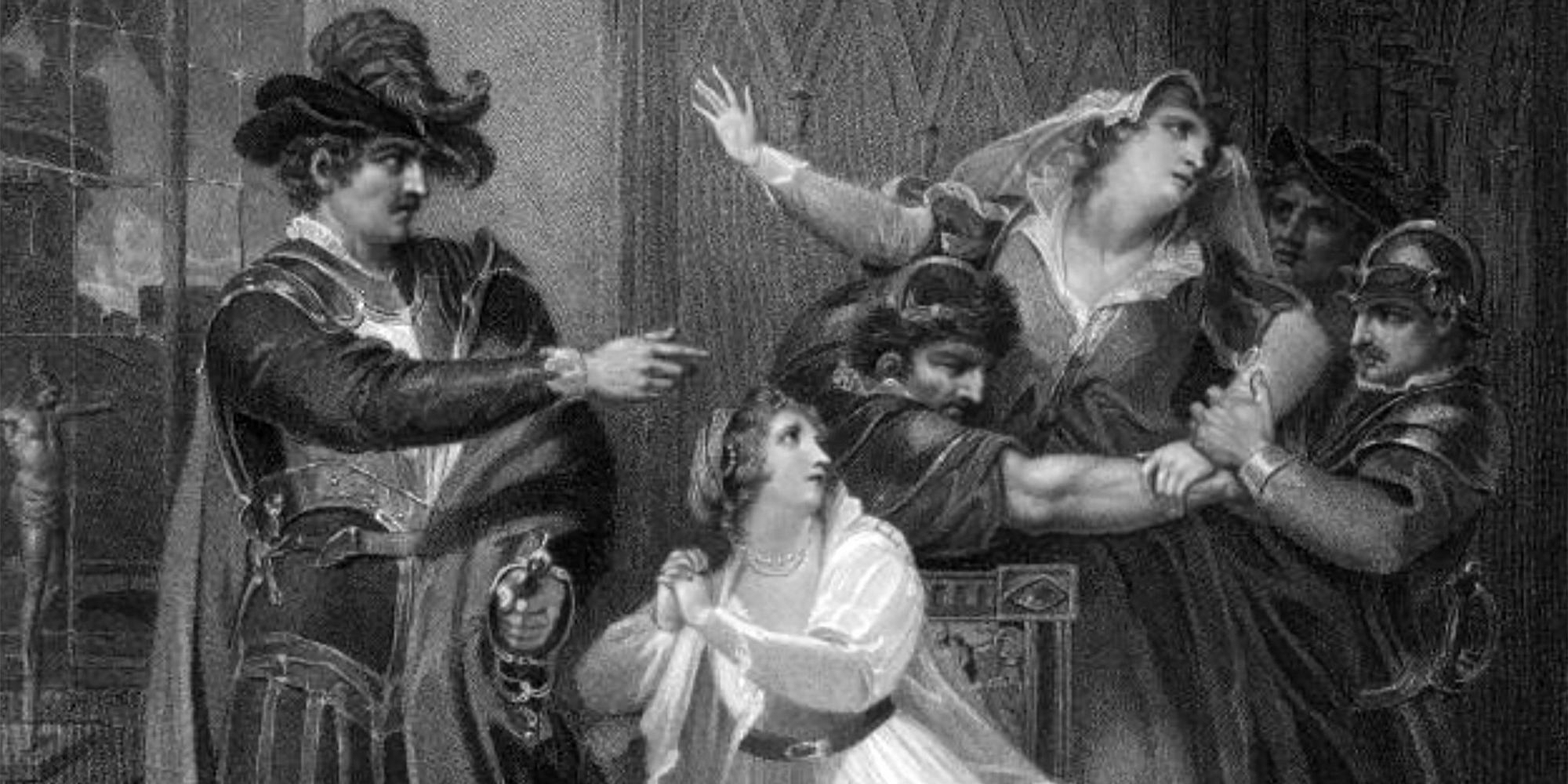

Image: The Mysteries of Udolpho by Ann Radcliffe. A 1796 engraving to illustrate the scene where Montoni at left orders his men to take Emily from the room against the wishes of Madam Montoni at right Contributor: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

The Italian

Ann Radcliffe