The Adventures and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

David Stuart Davies looks at the classic early short stories of Sherlock Holmes first published in ‘The Strand Magazine’.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes first appeared in the monthly periodical The Strand Magazine and it was this publication that secured star status for the author and his creation Sherlock Holmes. The publisher, George Newnes, wanted his new magazine to be ‘organically complete every month’ and so serials were out. In their place would be a selection of short stories. Arthur Conan Doyle saw this format as an ideal one for Sherlock Holmes, the hero of his two detective novels, A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of the Four. Each Holmes adventure would be ‘complete every month’ but the element of suspense and the interest in the character and his exploits would work like a serial, prompting the readers to buy the following issue to find out what the eccentric sleuth was up to next.

The first Sherlock Holmes story, A Scandal in Bohemia appeared in the July issue of The Strand in 1891 and attracted considerable attention. The die was cast. By the time the twelfth and final story of The Adventures (as they became known later), The Copper Beeches appeared, the Holmes tales had become the mainstay of the magazine.

Professor Moriarty – Strand magazine 1893

These are detective stories. I use this as a strict definition because that is what they are – stories featuring a detective. Not all of them are crime fiction narratives for in some no crime is committed. Doyle’s genius was in switching our attention from the puzzle, when there was one, to the solver of the crime. Holmes rather than the murder, the theft, the conundrum became the focus of the reader’s interest.

Take for example the first story in the collection, A Scandal in Bohemia. At first glance this may seem to have all the traits of a standard detective story: there is a problem, the detective is consulted and he sets about his investigations. However, while allowing his detective some excellent deductions, Doyle revealed this case as a failure for Holmes in the sense that his protagonist, Irene Adler, really gets the better of him. However, this was a master stroke for it reveals Holmes can be vulnerable to failure at times and this heightens the tension of the tales.

Doyle indulges his love of the bizarre and the gothic throughout this collection. These elements come together in a heady mixture in perhaps the best tale: The Speckled Band. This is not so much as a Whodunnit but Howdunnit. It is clear from the outset who the villain of the piece is. The mystery lies in his devilish, murderous modus operandi. Doyle plays straight with the reader: he provides all the clues so that like Sherlock Holmes they can reach the correct solution. The Speckled Band was one of Doyle’s own personal favourites and it still retains the power to chill and perplex today.

Before Arthur Conan Doyle had completed the first twelve short stories featuring his detective hero, he was already growing tired of the character. In fact, by the end of 1891 – halfway through his writing of The Adventures – Doyle had written to his mother, one of Sherlock’s greatest admirers, stating that he was thinking of ‘slaying Holmes in the last [story]. He takes my mind from better things.’ His mother prevailed upon him to change his mind, which for a time he did. Doyle’s disenchantment with Holmes had deepened further when the editor of The Strand Magazine requested a further twelve stories. In order to put him off, the author asked for what he considered to be the ridiculously high fee of £50 a story, fully expecting to be turned down. The Strand accepted his request without question.

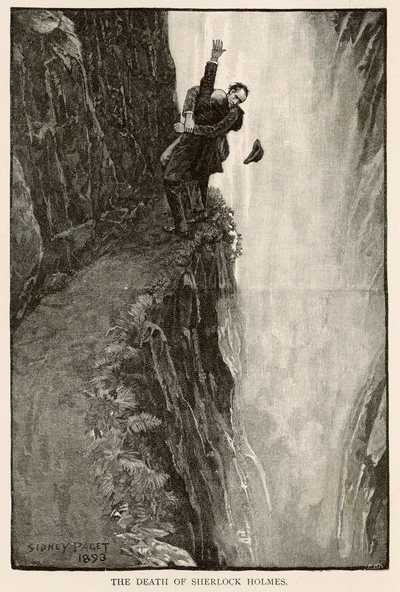

The Death of Sherlock Holmes

The second series of stories, which became known as The Memoirs, commenced with the story Silver Blaze which was published in the December 1892 issue. Already in this first story, there were signs that Doyle was having to stretch further to achieve a continuing freshness. Sometimes this led to moments which undermine the credibility of the plot or the character of Holmes. In the early part of Silver Blaze Holmes assures Watson that the train in which they are travelling is moving at ‘fifty-three and a half miles an hour.’ Holmes has deduced in a preposterous and probably impossible fashion by observing ‘the telegraph posts upon this line [which] are sixty yards apart and the calculation is a simple one.’ The calculation is not a simple one.

For further novelty, Doyle introduced two stories where the main actions of which take place before Holmes had met Watson. In essence then for the most part the narrator of these stories, The ‘Gloria Scott’ and The Musgrave Ritual, is Holmes himself, although the reader will not notice any significant difference in his narrative style to that of Watson. We catch a glimpse of Holmes in his youth and his student days, but Doyle is canny enough not to name which university – Oxford or Cambridge – was the master sleuth’s alma mater.

In The Greek Interpreter, we are introduced to Holmes’ brother, Mycroft. Until this tale, both Watson and the reader had no notion that the detective had such a sibling. Unlike his brother, Mycroft is lazy, corpulent and a founder member of the Diogenes Club, an establishment for the convenience of ‘the most unsociable and unclubbable men in town.’ While Sherlock Holmes is Bohemian and anti-establishment, Doyle presents Mycroft as a pillar of the establishment: in fact, Holmes states that Mycroft occasionally was the British Government.

The weary task of creating these stories convinced the author that they were to be the last featuring Sherlock Holmes. He determined to kill off the character and rid himself of this literary shackle. He began to make plans for Holmes’ death in the last story of The Memoirs.

Doyle realised that the end of Sherlock Holmes had to be very dramatic and had to be brought about by someone who was the detective’s intellectual equal. So he created a mastermind who was as brilliant at carrying out crimes as Holmes was at solving them. Enter Professor James Moriarty, ‘the Napoleon of Crime’, whom Holmes described as ‘the organiser of half that is evil and nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker.’ He was in essence Sherlock Holmes’ alter ego.

The scene of Holmes’ death in The Final Problem also had to be dramatic and special. While on a trip to Switzerland, Doyle encountered the magnificent waterfalls at Reichenbach. Here, he decided, was a suitably spectacular location for the death of ‘the most dangerous criminal and the foremost champion of the law of their generation.’ It was on the ledge overlooking the Reichenbach Falls that these two titans faced each other for the last time. With the demise of Holmes, Watson was beside himself with grief. So were the readers of The Strand. The offices were besieged with messages of grief, condolence and, most of all, anger – anger at the publication and the author for allowing this terrible incident to occur. Conan Doyle’s reaction was somewhat different: ‘Thank God I’ve killed the brute.’ Little did he know it at the time, but Doyle’s involvement with Sherlock Holmes was far from over. Somewhere in the near future, he would hear a tale of a phantom hound which terrified the moorland inhabitants of Devon and the deerstalker one would raise his head once more.

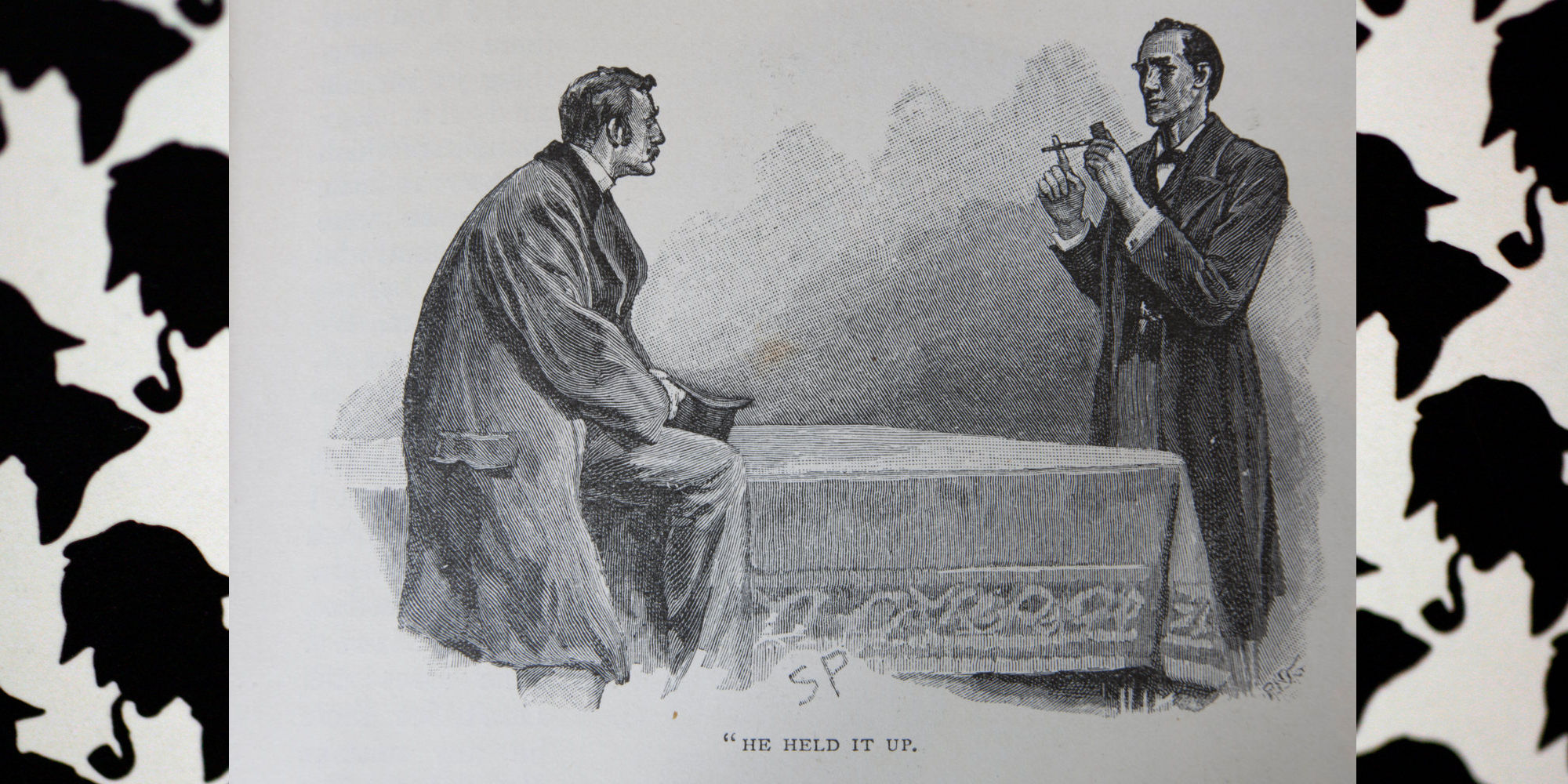

Images: The original artwork of Sidney Paget from ‘The Strand Magazine’.

Main image: Sherlock Holmes and Dr, Watson, Strand magazine, 1893

Contributor: Dave J Williams / Alamy Stock Photo

Above Top: Professor Moriarty Strand magazine 1893

Contributor: Dave J Williams / Alamy Stock Photo

Above Bottom: Holmes Moriarty 1893

Contributor: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

The Adventures & Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle