The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes

David Stuart Davies concludes his look at the complete Sherlock Holmes tales with this final collection of short stories

The Case-Book* is probably the most exotic of the Holmes collections which reveals that Conan Doyle’s vivid imagination was not flagging when he was writing these tales. However, it is fair to say that there is a certain shakiness in some of his plotting where issues are resolved perhaps a little too speedily or abruptly and sometimes without a completely satisfactory explanation. However, Doyle still remains bang on target in portraying the relationship between Holmes and Watson. This towers over the plots and adds an indefinable extra to these stories, imbuing them with a special quality that appeals to each succeeding generation.

The almost apologetic tone of Conan Doyle’s Preface to The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes – ‘I fear that Mr Sherlock Holmes may become like one of those popular tenors who, having outlived their time, are still tempted to make repeated farewell bows.’ – indicates to some extent that the author was aware that these stories were the last gasp of the detective’s oeuvre.

The author adds: ‘And so reader, farewell to Sherlock Holmes. I thank you for your past constancy, and can but hope that some return has been made in the shape of that distraction from the worries of life and stimulating change of thought which can only be found in the fairy kingdom of romance.’

This collection was first published in 1927 and at this time in Doyle’s life he had no real interest in Holmes at all. In fact in the final decade of his life – he died in 1930 – Doyle wrote hardly any fiction of any kind. His time, energy and enthusiasm were all directed to his work in the cause of Spiritualism. It was a belief that he had finally embraced after a lifelong search for the meaning of life and the pain of death. These late Holmes stories were penned purely as money-spinners, to provide cash for his Spiritualist crusade.

Not surprising then, The Case-Book is generally regarded as the weakest of the Holmes short-story collections. When a critic by the name of John Gore proclaimed the tales to be ‘very poor’, Doyle wrote to him saying, ‘I wonder whether the small impression which they produce upon you may be due to the fact that we become blasé and stale ourselves as we grow older… I test the Holmes stories on fresh young minds and find that they stand the test well.’ The author had a point. Familiarity does breed indifference if not contempt and one wonders how this collection would have been received if it had been the first.

The opening tale ‘The Mazarin Stone’ was actually based on Doyle’s own one-act play ‘The Crown Diamond.’ It betrays its theatrical roots by all the action taking place in one room. It is unique in the Holmes canon because the events are related by a third voice, with Watson relegated to the role of the listener as Holmes explains the case.

The result is stultifying and does prompt the question raised by John Gore’s criticism: are these stories really ‘very poor’? Not really, but they are somewhat disappointing in construction and surprising in their unpleasantness. While they may be weak in plot structure and development, they are fascinating because of the dark and cruel nature of their content. For example, physical disfigurement is featured in three of the stories. In ‘The Illustrious Client’, acid destroys the face of two of the characters. In ‘The Veiled Lodger’, the eponymous heroine is savaged by a lion leaving her with a ruined visage that challenges even Watson’s powers of description: ‘No words can describe the face when the face itself is gone. Two living beautiful eyes looking out of that grisly ruin did make the view more awful.’ The young man in ‘The Blanched Soldier’ suffers from leprosy, a disease that not only destroys the features but causes the sufferer to become an outcast from society. (This story is also unusual in that it is without Watson and narrated by Holmes himself in a style remarkably similar to the good doctor’s.)

The attempted murder of a baby features in ‘The Sussex Vampire’, which also has a dysfunctional marriage similar to the one in ‘Thor Bridge’, where the husband falls out of love with his wife who is of a different race and temperament.

Another instance of unpleasantness is Holmes’ uncharacteristically harsh treatment of the ‘Negro’, Steve Dixie in ‘The Three Garridebs’. The detective’s racist comments were hardly acceptable in 1926, let alone today:

‘I’ve wanted to meet you for some time,’ said Holmes. ‘I won’t ask you to sit down, for I don’t like the smell of you, but aren’t you Steve Dixie the bruiser?’

‘That’s my name, Masser Holmes, and you’ll get put through for it if you give me any lip.’

‘It is certainly the last thing you need,’ said Holmes, staring at the visitor’s hideous mouth.

It is difficult to believe that this passage was penned by the noble and chivalrous Arthur Conan Doyle.

Of course this collection contains the last Sherlock Holmes story that the author penned: ‘Shoscombe Old Place’. It is typical of all the fairly weak stories that Doyle wrote even from the days of The Adventures – stories such as ‘The Greek Interpreter’ and ‘The Engineer’s Thumb’. All these tales contain exciting, bizarre and very satisfying dramatic touches, but they do not quite gel and the denouement is disappointing and somewhat anti-climactic. In ‘Shoscombe Old Place’ we have an intriguing puzzle, a cunning villain and a strong mood of the gothic imbued in the plot, but somehow these elements do not mesh effectively and so it is sad to say that the Holmes canon closes with a whimper rather than a bang.

Taken as a whole, this dark and cruel collection clearly exposes the thinking and demeanour of Holmes’ creator in old age. Doyle demonstrates in these tales more than ever that he sees the harshness of the little life we live and feels inclined to reflect this in the final adventures of his greatest character.

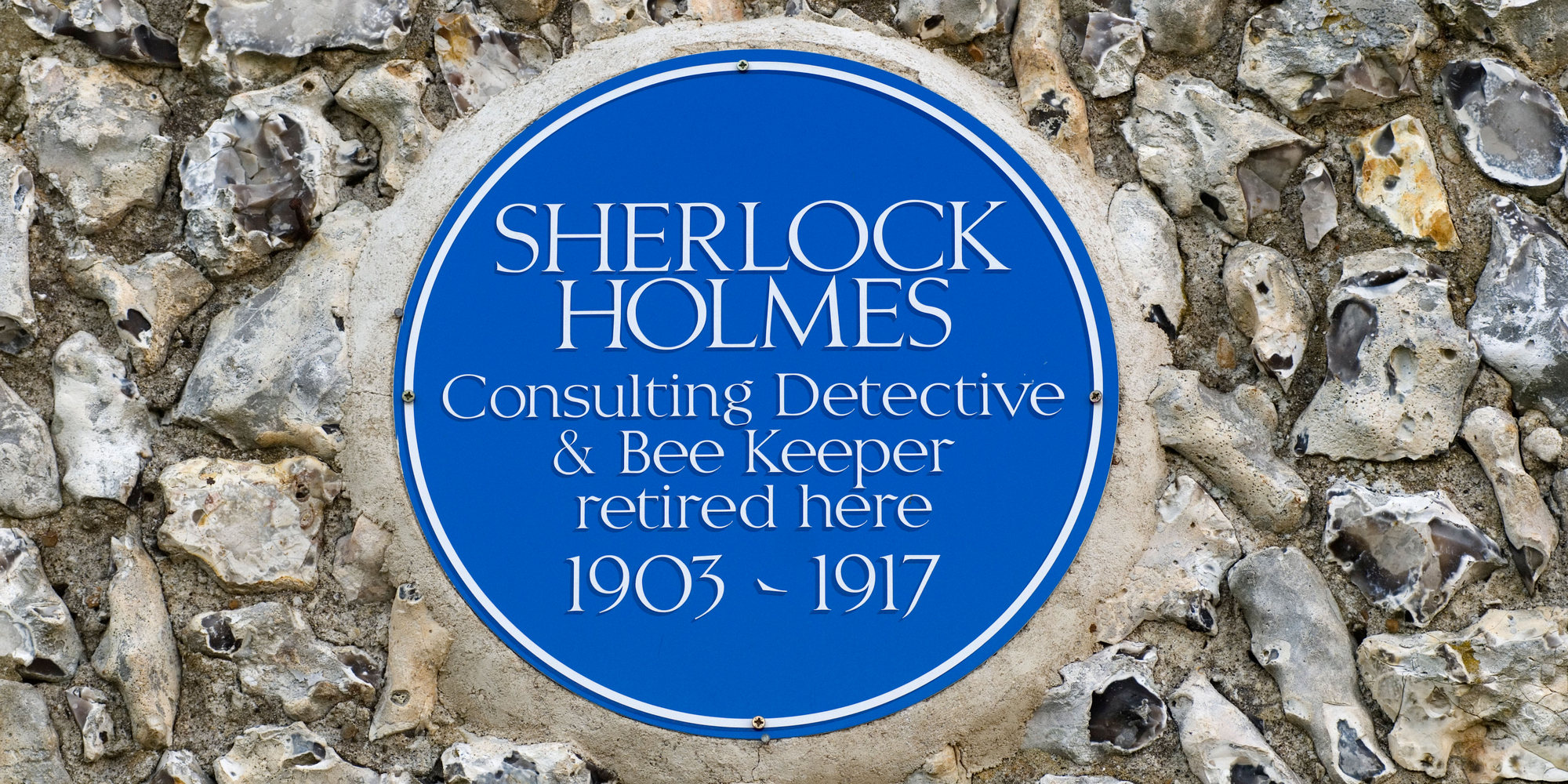

Image: Sherlock Holmes blue plaque in East Dean, near Eastbourne, East Sussex and not far from the excellent Tiger Inn, from back in the day when you could go in a pub.

Contributor: Homer Sykes / Alamy Stock Photo

*DSD has retained the original English title in his article, the U.S. edition was originally Case Book as two words, and somewhere along the line it became one word, as we have used in our edition.

Books associated with this article

The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes & His Last Bow

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle