The ‘Strand Magazine’ – Part One

David Stuart Davies reveals there was far more to ‘Strand Magazine’ than just Sherlock Holmes.

In the latter years of the nineteenth century, there was an increase in literacy in Britain. This was catered for by the growth of reasonably priced periodicals full of gripping stories and fascinating articles. Of course, in those far-off gaslit days, reading was the main form of domestic entertainment and these publications were devoured by an eager public desirous of vicarious divertissements. Long train journeys also provided those intervals when there was the opportunity to lose oneself in a good magazine, a wide selection of which was so readily available at the ubiquitous railway bookstalls.

The publisher George Newnes was shrewd enough to want to hitch a lift on this particular bandwagon. On the profits of his remarkably successful weekly paper Tit-Bits, he founded the Strand Magazine in 1890 after carefully surveying the potential market.

Edited by H Greenhough Smith from 1891 to 1930, the Strand aimed at a mass market family readership. The content was a mixture of factual articles, puzzles and short stories, most of which were illustrated. Despite expense and production difficulties, Newnes aimed at having a picture on every page – a valuable selling point at a time when the arts of photography and process engraving were in their infancy. ‘A monthly magazine costing sixpence but worth a shilling’ was the slogan the publicity-conscious Newnes used to advertise the Strand – which was half the price of most monthlies of the period.

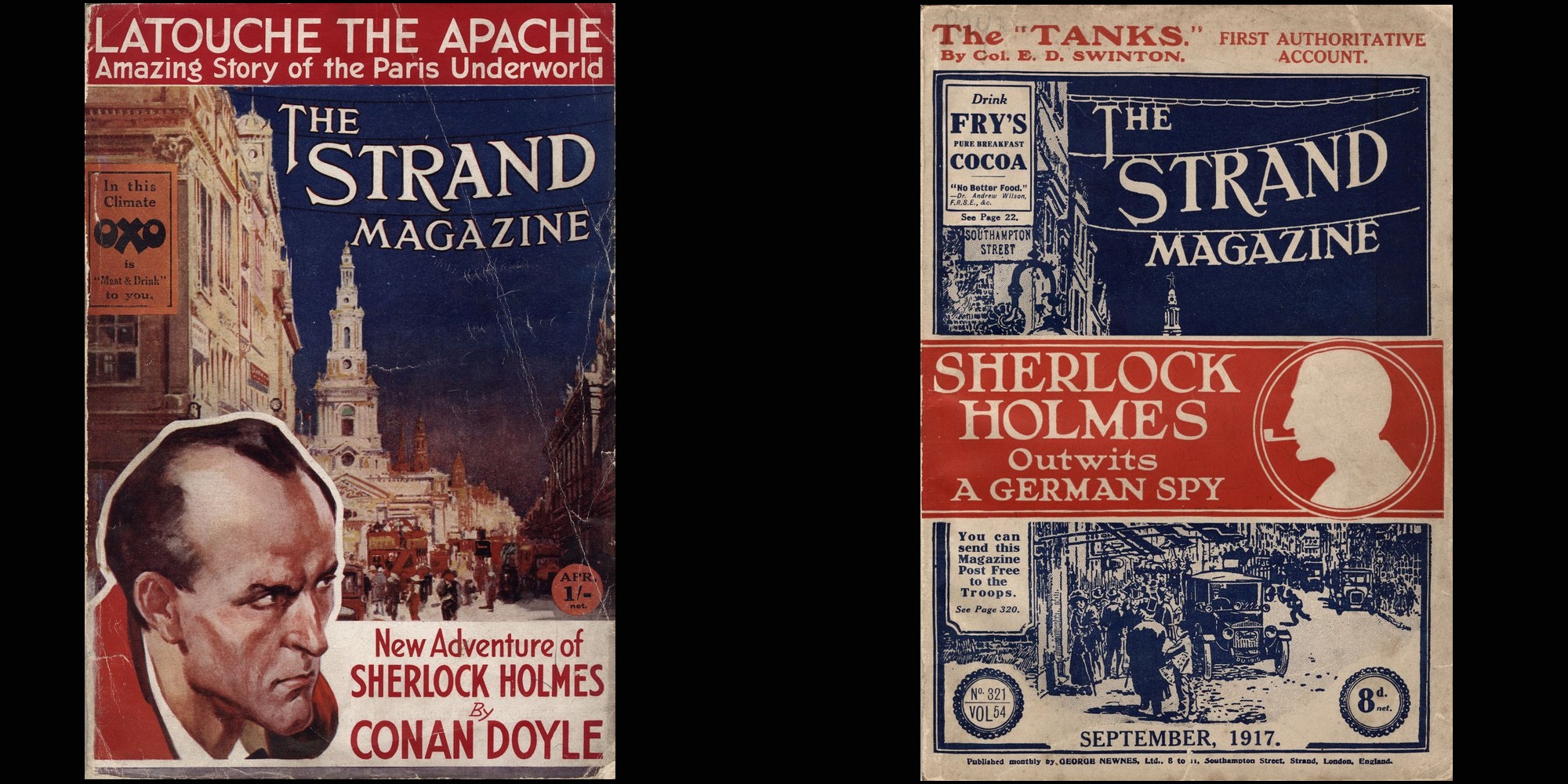

The magazine’s iconic cover, an illustration looking eastwards down London’s Strand towards St Mary-le-Strand, with the title suspended on telegraph wires, was the work of Victorian artist and designer George Charles Haité. The initial cover featured a corner plaque showing the name of Burleigh Street, home to the magazine’s original offices. In fact, for a time the publication was to be called The Burleigh Street Magazine. Newnes resolved that the magazine should be organically complete every month ‘like a book’ and so initially the notion of serials was spurned. With 112 pages of articles and stories, its advertising pages burgeoning with signs of prosperity, the first issue sold 300,000 copies. No other British or American publication approached these sales figures at the time.

The early issues contained work by many foreign authors including Balzac, Pushkin, Lermontoff and Dumas, but their offerings were not seen as the best that the Continent was producing. Nor were the British writers in any sense superior: J. E. Preston Muddock (Dick Donovan), E.W. Hornung (before he had got into his stride and created Raffles, the gentleman thief), W. Clark Russell and Bret Harte. There was also an anonymous short story, ‘The Voice of Silence’, which struck a note of novelty by having a phonograph indispensable to the plot, providing it with an ingenious twist. The little-known author was a certain Arthur Conan Doyle.

While the Strand was proving popular, the magazine world was an uncertain one, and although initially sales were encouraging, the magazine may not have survived if it had not been for a certain Scottish doctor, the author of that engaging story ‘The Voice of Silence’ and his detective creation.

When the first Sherlock Holmes short story ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ was published in the July 1891 issue of the Strand, circulation rose immediately. And the readers who were initially entranced by the Baker Street sleuth stayed with the magazine to read more of the detective’s exploits. This was partly due to a ploy of Holmes’ creator. In his autobiography, Memories and Adventures, published in 1924, Conan Doyle revealed that he had written the Holmes short stories with a view toward establishing himself in the Strand. He recalled that ‘A number of monthly magazines were coming out at that time, notable among them was the Strand, under the very capable editorship of Greenhough Smith. Considering these various journals with their disconnected stories it had struck me that a single character running through a series if it only engaged the attention of the reader, would bind that reader to that particular magazine … Looking around for my central character, I felt that Sherlock Holmes, who I had already handled in two little books, would easily lend himself to a succession of short stories’.

Indeed, the plan worked. While sticking to Newnes’ precept of avoiding serials, allowing the magazine to be complete every issue, the lure to purchase the following edition was to read a further adventure of the brilliant Mr Holmes. Within two years, the combination of Sherlock Holmes and the Strand had made Conan Doyle one of the most popular authors of the age. Fifty-six Holmes stories appeared in the magazine from 1891 to 1927, many of them illustrated by Sidney Paget’s now famous drawings.

However Doyle soon tired of Holmes along with the wearisome task of creating plot after plot and after the first set of twelve stories, he decided to cease writing about the detective. Desperate to retain their goose who was laying such profitable golden eggs, Greenhough Smith agreed to pay Doyle the magnificent sum of £1000 per story for the second series of tales. It was an offer the author could not refuse.

Conan Doyle was to prove one of the Strand’s most popular and prolific contributors. From mid-1891 until his death in 1930, there was scarcely an issue which did not contain at least one of his stories or articles. The serialisation of The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1901-1902 was estimated to have increased the magazine’s circulation by 30,000, with Conan Doyle being paid between £480 – £620 per episode, depending on length. The Strand also published Conan Doyle’s historical fiction such as Rodney Stone and The Adventures of Brigadier Gerard as well as his Professor Challenger stories including The Lost World.

When Doyle killed off his Holmes at the Reichenbach Falls (if only temporarily), he did indeed leave a significant gap in the Strand’s crime fiction section. Smith was very keen to fill this with another charismatic detective to emulate Sherlock. This task fell to Arthur Morrison with his investigator Martin Hewitt, who one critic described as a ‘low-key, realistic, lower-class answer to Sherlock Holmes.’ Though ostensibly Hewitt depends on logic to solve crimes (‘…I think I must ask you to begin at the first robbery and tell me the whole tale in proper order. It makes things clearer, and sets them in their proper shape.’), the stories tend to hinge on a clever gimmick. Sometimes all of the clues are provided for the reader to guess the solution, but for the most part, one can only marvel at Hewitt’s cleverness in figuring out bizarre solutions, and accept the complicated scenario he presents. Morrison provided seven stories featuring Hewitt in 1894 for the Strand, all illustrated by Sidney Paget, before decamping with his character to the rival publication The Windsor Magazine.