The supernatural fiction of Edith Wharton

Steve Carver discovers the supernatural fiction of Pulitzer Prize-winning author.

The Mount in Lenox, Massachusetts is the house that Edith Wharton built. She designed it as an elegant retreat from New York society in which she could write and her mentally ill husband, Teddy, could hopefully find some peace. The couple lived within its white stuccoed walls from 1902 to 1911, by which point their marriage was on the verge of collapse and Wharton was a respected author. The Mount became a National Historic Landmark in 1971, and it remains a museum dedicated to Wharton, putting on public lectures and panel discussions, dramatic readings, workshops, concerts, and film screenings. It also has a reputation as one of the most haunted houses in America. In grounds which include an Italian walled garden, a Georgian Revival gatehouse, a stable, and a pet cemetery, the Mount, complete with dark shutters, a coarse stone base, balustrade, and cupola, certainly looks the part. There are ‘ghost walks’ for the tourists, and the paranormal reality series Ghost Hunters broadcast two shows from the house, where, it is said, pale faces gaze from the windows of empty rooms, footsteps can be heard along the marble halls (believed to be Wharton’s maid, Catherine Gross), and shimmering orbs dance in the moonlight. Like something out of a novel by Shirley Jackson, the spirit of a pregnant chambermaid who hanged herself when her lover rejected her has been seen swinging from the upstairs landing where she died. The apparition of a man ‘with glowing eyes’ was reported by a builder working in an upstairs apartment, while a shadowy figure has been seen wandering the woods that surround the house for decades. Mediums have claimed that the heart of the house is Teddy’s study, in which several female visitors have reported having their hair pulled.

Rumours of hauntings began when the house was converted into a school for girls in the 1940s. These stories intensified after the Mount became the base for a Shakespearean theatre company in the 1970s, although it wasn’t paranormal activity that drove out the actors but a dispute with their landlords. And although it is quite a creepy-looking house, it is more than likely that the root of most if not all of these eerie legends are the ghost stories of Wharton herself, transposed onto the house in which she wrote several of them while making her name as a serious novelist.

Wharton had modelled the Mount on Belton House in Lincolnshire, a 17th century country house where, incidentally, a black-clad spirit is reported to haunt the bedchamber reserved for royal visits. The build was a collaboration with the architect and interior designer Ogden Codman Jr, a close friend with whom she had co-written The Decoration of Houses (1897), a popular and influential manual of interior design that eschewed Victorian ornament in favour of classical symmetry, simplicity, and order. Despite the success of The Decoration of Houses, financing the project was tight. Wharton was in a legal battle with her brothers over her mother’s will and she was still some years away from literary success and a stable, independent income.

Wharton wrote prolifically at the Mount, producing six novels including her literary breakthrough, The House of Mirth (1905), and her masterpiece, Ethan Frome (1911). She also authored four nonfiction books on interior design and travel there, a collection of poetry, and three collections of short stories, ending with Tales of Men and Ghosts (1910). She wrote fondly of the house in her memoir, A Backward Glance (1934), though she said little about her husband’s degenerating state of mind, his numerous infidelities, or the verbal and physical abuse she experienced behind those dark green shutters. ‘Teddy Wharton seems to be losing his mind,’ Codman had written while working on the house, ‘which makes it very hard for his wife.’ Instead, the trauma of this loveless, childless, and volatile marriage seeped into her fiction. If there is any sort of ghostly presence in the Mount, it is probably the echo of a brilliant, lonely, and frightened woman whose only possibility of escape from her miserable marriage was through her writing.

The young Edith Wharton

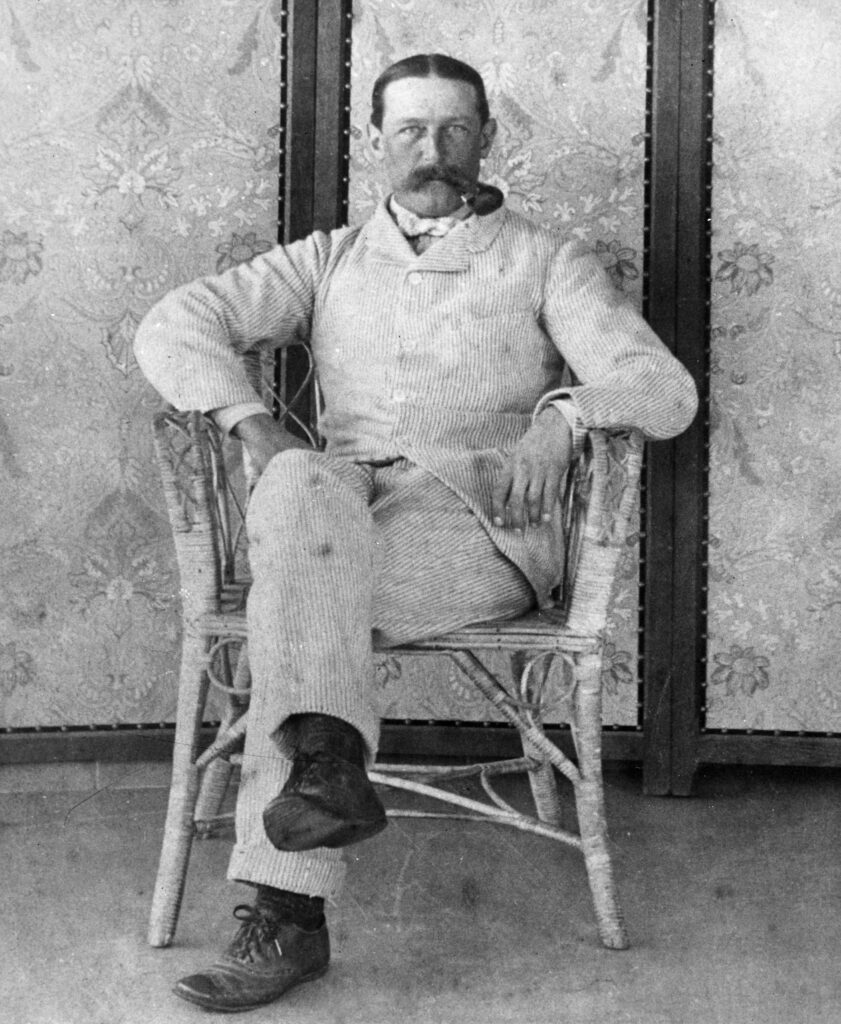

Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones in 1862. Her family’s immense wealth and attendant social status was founded on real estate, and legend has it that they were the origin of the phrase ‘keeping up with the Joneses’. They wintered in New York, had a summer house in Newport, and travelled extensively in Europe. Wharton began writing stories as a child, something her family discouraged as not being a suitable direction for a young lady of quality. She came out as a debutante in 1879 and in 1885 married Edward Robbins ‘Teddy’ Wharton of Boston. Edith was 23, Teddy was 35. Like his wife, Teddy came from old money. The couple shared a love of foreign travel, but he was not her intellectual equal. He was by all accounts an imperious man, also subject to hysterical mood swings and periods of intense despair, a manic condition inherited from his father, who had died in an asylum. Teddy took his many frustrations out on his wife, and close friends including Henry James urged her to leave him. By 1908, Teddy’s mental illness was deemed incurable. Wharton had meanwhile begun an affair with William Morton Fullerton, a foreign correspondent for The Times, and the couple finally divorced in 1913 after 28 years of marriage.

Wharton relocated to France the following year, despite the outbreak of war, and lived there for the rest of her life, visiting the US only once, in 1923, to receive an honorary doctorate from Yale. During the Great War, Wharton worked tirelessly to support refugees, the unemployed, the injured and the infirm, using her society connections to raise money and her literary connections to raise awareness, encouraging America to enter the war. In 1916, she was awarded the Légion d’honneur for her war work. Wharton was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1927, 1928, and 1930 (losing to Henri Bergson, Sigrid Undset, and Sinclair Lewis), and counted among her close friends Lewis, James, Jean Cocteau, André Gide, and Theodore Roosevelt. She never remarried.

Unsurprisingly, isolation, loneliness, and loveless marriages haunt Wharton’s realist fiction, which is an elegant commentary on the mores of the class to which she belonged through the ‘Gilded Age’ of American ascendancy – a period of industrialisation and rapid growth followed by war and economic depression. The House of Mirth, for example, charts the downward spiral of the high-born but penniless Lily Bart as she searches for a suitable husband until she is destroyed by the elite New York society that she is at once part of and excluded from. The bleak and claustrophobic Ethan Frome (1911) is the story of a tragic love triangle between poor farmer Ethan, his bitter and profligate wife Zeena, and her cousin Mattie, who is as warm as Zeena is cold. In her Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Age of Innocence (1920), the New York lawyer Newland Archer cannot marry the women he loves, the unconventional European divorcee Ellen Olenska, because of the social constraints and disapproval of his class, who steer him towards Ellen’s more socially acceptable cousin.

Although perhaps less well known as a writer of ghost stories, Wharton’s supernatural fiction continues to explore these themes by other means. Her relationship with the genre is fascinating. Her first ghost story, ‘The Fulness of Life’, was published in Scribner’s in 1893, only 18 months after she started writing for the magazine; her last, ‘All Souls’’ – not just her final ghost story but the last story she ever wrote – was written especially for an anthology of otherwise previously published stories, Ghosts, in 1937, the year Wharton died. Compiling this collection of what she considered her best supernatural fiction and writing ‘All Souls’’ was Wharton’s final authorial act. In her preface to Ghosts, she wrote that ‘I don’t believe in ghosts, but I’m afraid of them.’ This fear went back to her childhood. When she was nine, she contracted typhoid and was bedridden for weeks. All she could do was read, and although her mother restricted her access to novels, two friends lent her a children’s book that was considered to be innocuous. This was not the case. ‘To an unimaginative child the tale would no doubt have been harmless,’ she wrote in her posthumously published memoir, Life and I (essentially the first draft of A Backward Glance), continuing: ‘but it was a “robber-story” and with my intense Celtic sense of the supernatural, tales of robbers and ghosts were perilous reading.’ The title of this book remains a mystery, but perhaps because of her sheltered life, or more likely amplified by fever, the shock of reading triggered a relapse from which she eventually awoke changed:

When I came to myself, it was to enter a world haunted by formless horrors. I had been a naturally fearless child; now I lived in a state of chronic fear. Fear of what? I cannot say – and even at the time, I was never able to formulate this terror. It was like some dark, indefinable menace, forever dogging my steps, lurking, and threatening; I was conscious of it wherever I went by day, and at night it made sleep impossible, unless a light and a nursemaid were in the room.

Bizarrely, though Wharton was a declared fan of the uncanny tales of Scott, Hawthorne, and Poe, the supernatural fiction of M.R. James and Walter de la Mare, and a champion of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw – ‘which stands alone among tales of the supernatural’ – she further confessed in Life and I that she could not bear to sleep in a room with a book containing a ghost story until she was almost 30, adding that ‘I have frequently had to burn books of this kind because it frightened me to know they were downstairs in the library.’ (As with Teddy’s illness, these recollections were omitted from A Backward Glance.) It is notable that in these obviously traumatic memories, the fear was never of the supernatural but its textual representation. The young Wharton was not afraid of ghosts per se, but of books about ghosts.

In her preface to Ghosts, Wharton wrote that ‘The only suggestion I can make is that the teller of supernatural tales should be well frightened in the telling.’ The childhood ‘terror’ that Wharton could not name thus permeates her supernatural fiction, its very ambiguity unsettling, her position of fearing but not believing in ghosts becoming a fluid space between that which we can reasonably know and explain, and that which we do not or cannot. It was in this liminal realm that Wharton continued to explore and interrogate her own social class, saying as much if not more about the living than the unquiet dead.

In much the same way, Wharton’s writing historically inhabits that misty middle ground between 19th century Realism and literary Modernism. And although she was frequently criticised by ‘Naturalist’ writers for her privileged worldview – Alfred Kazin wrote that ‘The luxury that nourished Edith Wharton and gave her the opportunities of a gentlewoman cheated her as a novelist’ – her supernatural fiction can be as experimental and conceptually abstract as that of early and proto-Modernist authors like Joseph Conrad and Henry James. Kazin, a child of Jewish immigrants who wrote about the American immigrant experience, unfavourably contrasted Wharton’s work with that of Theodore Dreiser, another Naturalist, and the author of An American Tragedy (1925). Similar to Realism in its rejection of Romanticism, Naturalism is however distinguishable through its commitment to social commentary, authorial detachment, and determinism. It is not ‘realist’ so much as raw. In this sense, it is the precursor of some aspects of literary Modernism, particularly its politics and its freedom of expression, portraying human drives not normally discussed or depicted by Victorian novelists. James Joyce’s early fiction, for example, was hugely influenced by Naturalism. But the Naturalists did Wharton a disservice. She was simply doing what all authors are advised to do, that is writing about what she knew. While Kazin and Dreiser wrote from and about the working class, her subjects were the old families and the nouveau riche who comprised the East Coast elite, the subsequent tensions between tradition and modernity (old and new money), and the position of women in this world: constrained by social conventions, silenced, and sexually repressed. Many of her stories thus deal with confinement and secrets, the uncanny epiphany often a revelation of a long-buried truth. In her ghost stories, these concerns place her firmly in the realm of the ‘Female Gothic’, a term coined by Ellen Moers in Literary Women (1976) to describe how women writers in the 18th and 19th centuries used coded expressions to describe anxieties over domestic entrapment and female sexuality. While her realist fiction concentrates on the stifling nature of social convention, her supernatural fiction places her in a long line of women using the gothic to explore gender politics, from Mary Shelley to Wharton’s Modernist contemporary May Sinclair.

Edith Wharton c.1905

For Wharton, marriage was an endless resource for subtle tales of terror, with the supernatural used to explore and expose the darkest motivations of the living. In ‘The Lady’s Maid’s Bell’ (1902), one of her earliest ghost stories (some critics say the first), a new maid (‘Hartley’) comes to work in a remote house full of secrets, replacing a maid who died after twenty years of devoted service to the lady of the house. Mrs. Brympton is ‘nervous’ and ‘vapourish’ and her house is ‘big and gloomy’. She has outlived her children and her volatile and predatory husband prefers travelling to her company. It is hard not to think of Teddy, as Brympton is ‘the kind of man a young simpleton might have thought handsome, and would have been like to pay dear for thinking it.’ Hartley is spared his attentions as she’s recovering from typhoid and not considered attractive enough to seduce (or by implication, assault). On the rare occasions Brympton is at home the atmosphere is tense; whatever he wants from his invalid wife, she isn’t giving it, and the servants frequently hear them arguing. Mrs. Brympton’s only social contact is with the kind and bookish Mr. Ranford, a distant neighbour who may or may not be more than a friend. When she arrives, Hartley sees a ‘thin woman with a white face’ who she assumes is the housekeeper, though every time she mentions her the other servants change the subject. And there is no housekeeper. The room opposite Hartley’s is always locked too, and nobody will talk about that either… As the story unfolds, Hartley makes no attempt to explain or interpret events; she simply reports what she witnessed. And what she saw was Mrs. Brymton’s dead maid, Emma Saxon, apparently still protecting her mistress. What she is protecting her from is never made clear, and the ghost seems harmless and non-threatening, unlike Brympton. The climax is a masterpiece of understated gothic equivocation, and the author leaves it up to us to follow the clues seeded in the narrative and arrive at our own conclusion. Like Henry James in The Turn of the Screw, she makes us work to find meaning, while its lack emphasises the uncanny charge of the tale. It is the disconnect between different and nuanced interpretations within the text that generates readerly unease. In her preface to Ghosts, Wharton had written of the difference between ‘ghost-seers’ and ‘ghost-feelers’, and it is to the latter camp that many of her stories, including this one, belong, eschewing the short sharp shockers of contemporary hair-raisers like M.R. James and E.F. Benson, who delivered much more decisive gothic punchlines.

‘The Fulness of Life’ (1893), had been a very different tale in form and tone, although the subject remains the same, the title an ironic reference to what the unnamed female protagonist did not experience through her marriage when alive. The story is almost magic realist, which may explain why it is invariably included in anthologies of Wharton’s ‘supernatural’ fiction while not being counted by some critics as her first ‘ghost’ story. This seems to me to indicate a rather dogmatic approach to the genre that also misses the point of Wharton’s ongoing paranormal project. In ‘The Fulness of Life’, the wife of an oafish, upper-class man is offered the chance of a more compatible love in the afterlife. But even in death, she finds herself unable to escape her wifely responsibilities to her annoying and rather boring spouse, who shares none of her passion for art and culture. It is a painful confession of duty and domestic unbliss hidden in an ironic quasi-Spiritualist fairy tale – she meets the ‘Spirit of Life’ not Saint Peter – that Wharton later described as ‘one long bleat’. Again, one thinks of Teddy, this time not as the brutish philanderer of ‘The Lady’s Maid’s Bell’, but as an uncultured boor. ‘A Journey’ (1899) recalls Milton’s metaphor for an unhappy marriage in his Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (1644) as being like ‘two carkasses chain’d unnaturally together’. The story maintains a level of suspense worthy of Hitchcock and a premise that would suit an EC horror comic as the wife of an invalid attempts to conceal her husband’s death in a sleeping car long enough to get home to New York. In ‘Bewitched’ (1925) – a kind of haunted Ethan Frome – and ‘Pomegranate Seed’ (1931) – which may well have inspired Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca – two women from very different social backgrounds come to realise that the ‘other women’ that have a hold over their husbands are dead. ‘Pomegranate Seed’ is an intense and claustrophobic character study of a bourgeoise second wife trying to hold her outwardly prosperous family together as her husband becomes more distant and secretive. ‘Bewitched’, like Ethan Frome, takes place in a stark, wintery, and unforgiving rural working-class community where superstition is rife but not necessarily without foundation, folklore being another important component in several of Wharton’s stories.

Wharton also wrote spooky historical stories inside contemporary frames, as well-to-do narrators (like her) uncover the grim secrets of houses they consider renting, or in one case inherit, in Europe. ‘The Duchess at Prayer’ (1900) and ‘Kerfol’ (1916) recall the medieval horrors of Poe. In both stories, an uncanny encounter leads the narrator to dig deeper, after which the primary tale takes over, through a servant’s ancestral anecdote in ‘The Duchess at Prayer’ and ancient legal transcripts in ‘Kerfol’. As ever, Wharton leaves her conclusions hanging, the creeping horror of the tales concerned more with the virtual imprisonment of the women in each story than the traditional gothic epiphanies hinted at in the framing narratives – a statue with a look of utter disgust on its face, and eerily quiet dogs hanging around the ‘most romantic house in Brittany’. ‘Mr. Jones’ (1930) moves the tragic backstory to England in the 18th century. Again, the story of an ill-used and lonely wife is revealed, her deafness and dumbness a bleak metaphor for her situation, metaphorically buried alive. She can only write letters which are ignored until another women, the protagonist of the contemporary part of the tale, finally listens, although by then, of course, it is far too late. Nowhere in Wharton’s fiction is the obliteration of woman so absolute. The narrator, at one point, finds an elaborate monument to her male ancestor, while his wife’s details are no more than a chiselled footnote. Like ‘The Lady’s Maid’s Bell’, ‘Mr. Jones’ features the spirit of a devoted servant, only this time it is a manservant devoted to its master not its mistress, a patriarchal symbol that exerts huge power over the household despite barely being glimpsed. As each of these stories slowly reveals the appalling cruelty of aristocratic husbands towards their lonely wives, one is reminded of Kathy A. Fedorko’s analysis that Wharton used the gothic ‘to portray one “secret” in particular: that traditional society and the traditional home, with their traditional roles, are dangerous places for women.’

Edward Robbins Wharton c.1905

But not all of Wharton’s supernatural fiction is explicitly about marriage. As in her novels, she also writes about the shifting business paradigm of old and new money in her class, as those that coast on inherited wealth have no understanding of or defence against the new generation of robber barons that have supplanted them. In The Age of Innocence, this contrast is present in Newland Archer, whose family has not needed to work for money for several generations, and the ambitious and arrogant British banker, Julius Beaufort. ‘The Triumph of Night’ (1914) blends the gothic archetype of the doppelgänger with this conflict of interests, when a ruthless businessman’s true feelings about an indolently rich relative are manifest in the form of a baleful double that only a poor secretary can see. In ‘Afterward’ (1910), a business deal that is morally reprehensible but perfectly legal literally comes back to haunt its beneficiary, while there are no ghosts at all in ‘A Bottle of Perrier’ (1930), just a lingering sense of absence and class resentment.

Wharton’s other preoccupation in these stories was loneliness – already a feature in her view of marriage, but which she increasingly linked to the horrors of aging as she herself grew older. ‘The Eyes’ (1910), in which an elderly aesthete who exploits and discards both young men and women is haunted by ghostly eyes he never realises are his own, is clearly inspired by The Picture of Dorian Gray. The bitter-sweet ‘Miss Mary Pask’ (1925), with its lascivious ‘apparition’ of an elderly spinster, and the even more poignant ‘The Looking Glass’ (1935) deal with the horrors of growing old alone, against which the uncanny elements of each story feel almost comforting. Poor old Mary Pask isn’t exactly a ghost, but she might as well be, while the fading society beauty of ‘The Looking Glass’, Mrs Clingsland, is happy to be romanced by what she thinks is the spirit of a long-dead suitor. Both scenarios are almost comic, but Wharton coaxes out both empathy and tragedy, as well as more than a few chills.

But whatever the nature of the tale, Wharton’s prose is elegant and precise, and as balanced as her designs in The Decoration of Houses. As she wrote in The Writing of Fiction (1925):

It is not enough to believe in ghosts, or even to have seen one, to be able to write a good ghost story. The greater the improbability to be overcome the more studied must be the approach, the more perfectly maintained the air of naturalness, the easy assumption that things are always likely to happen in that way … The moment the reader loses faith in the author’s sureness of foot the chasm of improbability gapes.

In short, don’t overdo it, a lesson that 21st century supernatural fiction perhaps needs to re-learn. As Wharton further advises:

When the reader’s confidence is gained the next rule of the game is to avoid distracting and splintering up his attention. Many a would-be tale of horror becomes innocuous through the very multiplication and variety of its horrors. Above all, if they are multiplied they should be cumulative and not dispersed. But the fewer the better: once the preliminary horror is posited, it is the harping on – the same string – the same nerve – that does the trick. Quiet iteration is far more racking than diversified assaults; the expected is more frightful than the unforeseen.

This is similar to H.G. Wells’ personal ‘rule’ of science and supernatural fiction that the author should limit themselves to a single fantastic event in a narrative, maintaining otherwise a strict sense of realism throughout.

The use of ‘quiet iteration’ is perhaps most beautifully realised in Wharton’s final story, ‘All Souls’’ (1937), in which her as ever realistic social world is subject to an uncanny interruption. In this story, Wharton seems to confront her own impending death, returning in many ways to her first supernatural story, ‘The Fulness of Life’, thereby closing a circle 44 years in the making. As illness or accident often trigger Wharton’s supernatural stories, the robust if elderly widow, Sara Clayburn (‘of good colonial stock’), takes to her bed after badly spraining her ankle. This injury occurs after Clara meets a mysterious woman apparently on the way to visit one of her servants on Halloween. At one level, this is all about every elderly person’s fear of losing independence, of suddenly becoming helpless and reliant on others, in this case servants. But the servants aren’t there. Mrs. Clayburn awakes to find her house completely silent, completely empty, with no evidence of trouble, and no explanation ever given… The story again has a framing narrator, who has written down ‘the gist of the various talks I had with cousin Sara’ with a view to recording ‘the few facts actually known’. This is an elegant device similar to that of the narrator of ‘Kerfol’, who paraphrases rather than transcribes the account of the trial of Anne de Cornault, while claiming not to be adding ‘anything of my own’ to the story. In fact, this act of retelling adds another layer of distance to the tale, while claiming authenticity through the apparent use of Sara’s testimony. As the ‘calm’ and ‘matter-of-fact’ Sara waits in bed for her maid and the clock ticks on, she begins to realise something is not right, despite rationalising the situation.

As she begins to tentatively explore, it is the ‘cold unanswering silence of the house’ that forms the true horror of the tale – a deathly silence we might say:

More than once she had explored the ground floor alone in the small hours, in search of unwonted midnight noises; but now it was not the idea of noises that frightened her, but that inexorable and hostile silence, the sense that the house had retained in full daylight its nocturnal mystery, and was watching her as she was watching it; that in entering those empty orderly rooms she might be disturbing some unseen confabulation on which beings of flesh-and-blood had better not intrude.

The tradition ‘haunted house’ at night is turned on its head yet at the same time symbolically retained. The ‘deep nocturnal silence’ is much more awful in the daytime, which should be full of the ordinary household noises of five servants going about their work. The ‘cold whiteness of the snowy morning’ – a recurring symbol in Wharton’s fiction – seems a literalisation of this silence, ironically painted a vast white rather than a midnight black. Although Wharton is not above using gothic archetypes like ‘haunted houses’ on dark, wild nights – for example in the setting of ‘Miss Mary Pask’ – she will often use such things to misdirect. Instead, her favoured technique is cheerfully explained in the narrator’s prefatory remarks to Sara’s story:

I read the other day in a book by a fashionable essayist that ghosts went out when the electric light came in. What nonsense! The writer, though he is fond of dabbling, in a literary way, in the supernatural, hasn’t even reached the threshold of his subject. As between turreted castles patrolled by headless victims with clanking chains, and the comfortable suburban house with a refrigerator and central heating where you feel, as soon as you’re in it, that there’s something wrong, give me the latter for sending a chill down the spine!

This is an important device in the development of the 20th century gothic, particularly in America, which does not have the millennia of history, tradition, and superstition that we take for granted in Europe. As the US comedian Phil Silvers was fond of joking, it’s a ‘young country’. The tropes and devices of the European gothic are thus transported to a much more modern American setting, a major part of the horror thus becoming the imposition of something ancient, superstitious, and inexplicable into a rational, knowable and contemporary environment. This technique can be seen clearly in the work of American horror writers like H.P. Lovecraft, Al Feldstein, Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, and probably most significantly of all, Stephen King. It is also the device that allows the Mount, built in 1901, to have more ghosts attributed to it than the Tower of London.

As is obvious right back to ‘The Lady’s Maid’s Bell’, to write about the upper classes is also to necessarily write about servants. Physically incapacitated as she is, Sara is particularly dependent on her servants. They, in turn, apparently have something going on beyond their job that is much more important than her, and there are hints that the mysterious woman encountered on the path might be another sort of mistress, one that belongs to a much more ancient world than Sara. The bridge between the two worlds is Sara’s maid, Agnes (one of many servant Agnes’ in Wharton’s stories), who ‘was from the isle of Skye’, and ‘the Hebrides, as everyone knows, are full of the supernatural.’ That said, Sara ‘could not believe that incidents which might fit into the desolate landscape of the Hebrides could occur in the cheerful and populous Connecticut valley.’ This, of course, brings us back to the eerie disruption of the modern by the ancient. But even though Sara ‘insisted that there must be some natural explanation’, having encountered the mysterious woman on the path again exactly one year later, she left the house never to return. Were the servants part of a coven that abandoned their mistress to perform unholy rites? Did Sara dream the entire episode of the empty house? Were the servants gaslighting her to make her believe she was dreaming? Is the icy silence a metaphor for death…? Wharton doesn’t tell us. As in all these stories, signs opaque and ambivalent are left for us to interpret. It is in this uncertain, metaphorical, and perhaps psychological space that the atmosphere of mystery and terror resides in all the best ghost stories, although in Wharton’s contributions to the genre it is often not the ghosts that are the scariest part.

Wharton may channel the folklore and superstitions of the ‘old countries’ to open an uncanny portal into the American present, but her subject is often a very human cruelty. Sometimes this is punished, mostly it is not. Invariably, the agents of this malice are male and not at all supernatural. If they were, they would be all the less disturbing for being creatures of fantasy. In Wharton’s uncanny universe, it is often the victims and the vulnerable that come back, either as spirits or simply as guilty secrets revealed. As a commentary on the dark side of the human condition, Wharton’s ‘ghost’ stories are as relevant now as they were at the turn of the last century. They also depict with unerring insight the ways that our ordinary lives can haunt us. Her stories are full of regret, poor choices, missed opportunities, and betrayals – universals all, along with the fear of growing old, especially alone. Being frequently of her class and thus rich, Wharton’s characters may be able to keep this at bay for a while, but they can’t outrun it forever. Life, she seems to be saying, will make ghosts of us all in the end.

Yet the ‘ghosts’ Edith Wharton wrote about were much more subtle and elusive than the garden variety apparitions attributed to her former home by creative tour guides and credulous paranormal investigators. Her ghosts come as much from within as from without, her hauntings as likely to be metaphorical as literal. Sometimes her ‘ghost stories’ don’t contain any ghosts at all… You may read as a Feminist, a Gothicist, a Realist, or a Modernist, and these stories will be equally engaging, chilling, and fresh. For a new Christmas ghost story experience, you could do no better. In her preface to Ghosts, her final collection, Wharton also offers these stories as a meditative antidote to ‘the hard grind of modern speeding-up’. Like us, she found herself in a loud and accelerated culture of mass media, new technology, and rapid social change, whereas ‘Ghosts, to make themselves manifest,’ she wrote, ‘require two conditions abhorrent to the modern mind: silence and continuity.’ It is the same for readers and writers. And in that quiet, archaic, and ineffable space, she promised, resides ‘the fun of the shudder’.

Main image: The Mount, Lenox, Massachusetts. Credit: Lee Snider / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Portrait of the young Edith Wharton by Edward Harrison May Credit: NMUIM / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Edith Wharton c.1905 Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Edward Robbins Wharton (1850-1928) c1905. Credit: Granger – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

For more information on Edith Wharton see: The Mount and The Edith Wharton Society

Books associated with this article