The Ghost Stories of Edith Wharton

Although best known for her novels such as the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton was a talented writer of supernatural fiction. David Stuart Davies takes up the story.

The genre of the ghost story has attracted writers from the highest echelons, none more so than the Pulitzer Prize winner, Edith Wharton. As a child and a young woman, she was obsessed by the supernatural and the terrors it could summon forth out of the darkness. During a bout of illness in her youth she read a ghost story and the experience brought about a relapse in her condition, endangering her life. Such was the power of supernatural fiction, and its influence was to stay with her all her life.

In time Wharton began writing her own ghost stories – maybe as some cathartic release from this strange and fearful obsession with the fiction of the supernatural. It is therefore surprising to read in the preface to her 1937 collection, Ghosts, her claim that she did not actually believe in ghosts, but added, ‘… I’m afraid of them.’ She admitted that this statement seemed like a cheap, catchpenny paradox but explained:

‘To ‘believe’ in that sense, is a conscious act of the intellect, and it is in the warm darkness of the prenatal fluid that the faculty dwells with which we apprehend the ghosts we may not be endowed with the gift of seeing.’

In other words, imagination is required, not belief. And Wharton was able to harness her own natural imagination, the wellspring of her youthful fears, which touches the reader with an electrical spark arcing from one vital point to another.

Edith Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones in 1862 to a wealthy New York family, so affluent that they were the source of the phrase, ‘Keeping up with the Joneses.’ Wharton developed into an artistic polymath. Besides her writing, she became a highly regarded landscape artist and interior designer, setting the trends for the smart set. She wrote several influential books on the subject of domestic design for both inside and outside the home, including her first published work, The Decoration of Houses (1898).

Literary critic Jack Sullivan has noted that in Wharton’s supernatural fiction, ‘it is [the] sharply felt sensation of supernatural dread filtered through a sceptical sensibility that made Wharton a master of the ghost story.’ Accepting this point, it is no surprise that she was an admirer of M.R. James and particularly her fellow countryman Henry James of whom Wharton observed, ‘[his] imaginative handling of the supernatural no one, to my mind, has touched.’ Her approach to frightening the reader was very similar to that of Henry James: her use of suggestion, the oddness of the moment, the uncertainty that enriches the narrative rather than the more graphic and visceral effect. Often her tales were shrouded in ambiguity – none more so than ‘The Lady Maid’s Bell’. Rarely have I known two readers reach the same conclusion regarding the mystery of this tale. It is unsettling and intriguing, as is most of life, Wharton seems to say, and it is up to you to interpret the drama.

The unhappiness that Wharton experienced in her marriage and her husband’s serial infidelities found a dark expression in her ghostly fiction. The implication of adultery is a common theme in her tales such as ‘The Duchess at Prayer’, a story of terror and punishment written very much in the style of one of her other literary heroes, Edgar Allan Poe. Eleanor Dwight, in her study of Wharton’s life and works, Edith Wharton: An Extraordinary Life (1994), suggests that this story reflects a plight familiar to Wharton and many young wives of the period, that of, ‘The woman abandoned by her husband for long periods of time and then expected to be sexually available to him when he returns.’

Perhaps Wharton’s strangest tale involving marital infidelity is ‘Bewitched’. This disturbing story is firmly located in a New England backwoods locale where a distracted wife is convinced that her husband is having an affair. But it is no ordinary affair: the husband in question is infatuated with a dead woman who, it seems, is returning his love. This, then, is a tale of vampirism, with echoes of Conan Doyle’s bizarre novella, The Parasite (1894), and a subject rarely touched upon by women writers at the time.

‘A Bottle of Perrier’, written in 1930, is particularly interesting because it is set in the African desert. It is a tale of murder and suspense, which attracted many notable literary admirers including Graham Greene who referred to it as ‘that superb horror story’. Its appeal and success is perhaps best summed up by Ellery Queen who wrote the following, after republishing the story in his magazine in 1948:

‘It has been said that Edith Wharton’s style is a ‘clear luminous medium in which things are seen in precise and striking outline.’ You will find that also true: the mystery and menace of the infinite sands, the enervating heat, the timelessness, the silence, the inaccessibility – all become luminous; but there is something else, something brooding and haunting, which becomes clear and finally emerges ‘in precise and striking outline…’

This story also demonstrates that one does not need gothic touches, old houses with dark corners or moonlit graveyards to produce fear and shivers in the reader.

It is generally considered that Wharton’s most chilling ghost story is ‘Afterward’. This also features a woman whose marital happiness is threatened by a seductive spirit. Again, the author uses ambiguity and sleight of hand to confuse the reader as to the ‘reality’ of the ghost’s presence. It is only ‘afterward’ – when the tragedy has taken place – that we are convinced that there really was a ghostly presence in the house.

It is what Jack Sullivan called the ‘suggestive vagueness’ that we find in this and most of Edith Wharton’s supernatural fiction which is most powerful and most effective. The stories grip and frighten because of our uncertainties, just as in the night when we waken from a troubling dream and see unsettling indistinct shadows in the room. That creeping uncertainty of what is really there in the darkness is the key. Edith Wharton knew that what frightened her – what caused her night-time terrors as a young girl – would frighten us, too. And the power of her stories to disturb and chill is still as potent today as it was when they were first created.

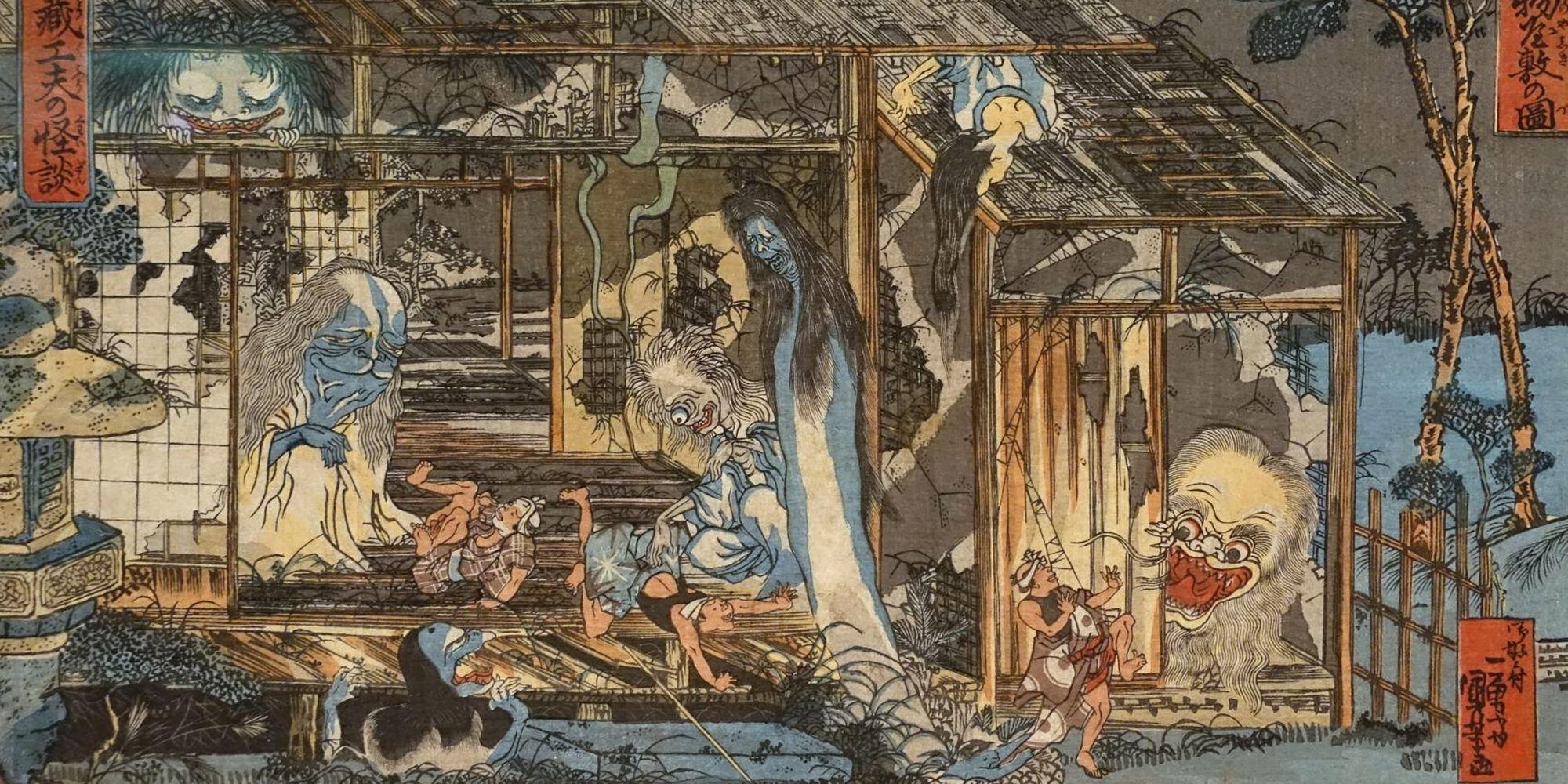

Main image: One Hundred Ghost Stories (Haunted House by Hayashiya Shozo) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Japan, Edo period, 1800s AD, woodblock print on paper. Credit: Magite Historic / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article