The Japanese Macbeth

Dr Stephen Carver looks at one of the most memorable adaptations of Macbeth, Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 film Kumonosu-jō, best known as Throne of Blood. The Japanese Macbeth

Macbeth is one of Shakespeare’s shortest tragedies, over a thousand lines fewer than both King Lear and Othello, and about half the size of Hamlet. Some literary historians go as far as to argue, in fact, that we are not in possession of the complete text, and that the recorded play is no more than a prompt-book, citing the difference between Quarto and Folio editions of Shakespeare’s other plays, the Quarto versions being generally longer. Macbeth was printed in the First Folio, but there is no Quarto version. The play therefore unfolds at a crisp dramatic pace, with few digressions and a lot of action. It thus translates incredibly well to film, and at time of writing there have been 48 film versions of the play (the first shot in 1905), with dozens of other general adaptations, such as Joe Macbeth (1955) and Men of Respect (1990), both of which relocate the action to the American criminal underworld and use modern dialogue while keeping to the story. On screen, Macbeth has been notably portrayed by Orson Welles (1948), Sean Connery (1961), Jon Finch (1971), Ian McKellen (1979), Patrick Stewart (2010), Michael Fassbender (2015), and Denzel Washington (2021). In such a crowded field, it might surprise you to learn that one of the versions most highly regarded by film and literary critics contains not a line from Shakespeare, and resides firmly in the ‘adaptation’ camp rather than ‘performance’. That film is Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 Kumonosu-jō – ‘Castle of the Spider’s Web’ – known in the west as Throne of Blood. The Japanese Macbeth

Shakespeare did not come to Japan in any meaningful way until the Meiji Restoration of 1868, the era during which Japan shed 250 years of strict cultural isolation, the Edo Period (1603 to 1868) foreign policy of Sakoku (literally ‘locked away’). Shakespeare was then banned again during the Second World War as was all non-Japanese art. During the war, the Japanese director in training Akira Kurosawa was learning his trade, playing cat and mouse with wartime censors over the clearly Hollywood-inspired gangster film Sanshiro Sugata (1943), and making propaganda movies like The Most Beautiful (1944), which celebrates wartime women factory workers, and a much more patriotic sequel to Sanshiro Sugata, in which the hero defeats an American boxer much as Sylvester Stallone would later best a Russian fighter in Rocky IV. Kurosawa’s father had been very open to western culture, and had encouraged his children to explore European and American theatre and cinema. Akira had been absorbing Shakespeare and Hollywood movies since he was six. While Kurosawa made his wartime movies, the young photographer Toshiro Mifune served in the Imperial Japanese Airforce as an aerial photographer and dreamed of being a cameraman in the growing Japanese film industry, if he survived the war. Like Kurosawa, Mifune was no cultural isolationist; his parents were Methodist missionaries and he had a natural gift for foreign languages.

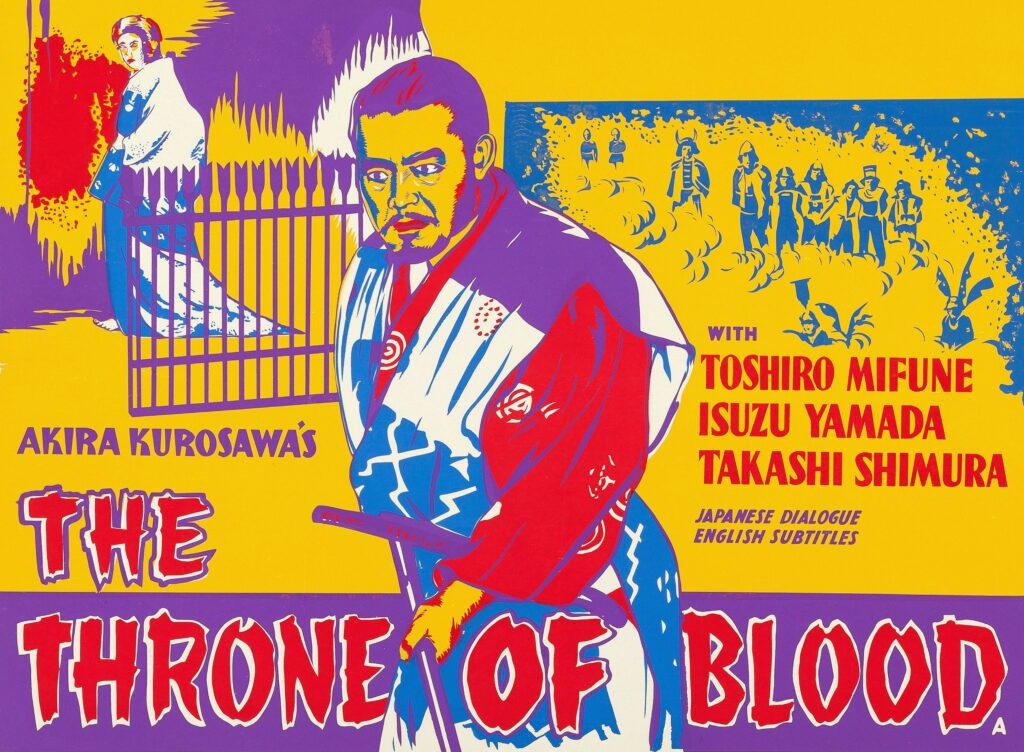

Vintage film poster for ‘Throne of Blood’ 1957

Kurosawa and Mifune first met a couple of years after the war, at a talent competition at Toho Studies, then and now the largest film production company in Japan. Mifune had been encouraged to get his foot in the door as an actor by a friend, though he still hoped to become a cameraman. In a screentest for Kurosawa’s mentor Kajirō Yamamoto, Mifune had channelled his wartime anguish when asked to mime ‘anger’, and landed a role in Yamamoto’s Shin Baka Jidai (‘These Foolish Times’) and Snow Trail (directed by Senkichi Taniguchi from a screenplay by Kurosawa) in 1947. Kurosawa was going to skip the Toho event, but the actress Hideko Takamine told him to go and look at Mifune. Kurosawa later described seeing ‘a young man reeling around the room in a violent frenzy’ and managing to alienate all the other judges. ‘It was as frightening as watching a wounded beast trying to break loose. I was transfixed.’ Exhausted, Mifune finished his scene, sat down and glared at the disconcerted judges with eyes of fire. He didn’t win the competition but Kurosawa and Yamamoto convinced Toho to sign him anyway. ‘I am a person rarely impressed by actors,’ Kurosawa later said, ‘but in the case of Mifune I was completely overwhelmed.’ The Japanese Macbeth

Mifune’s first film with Kurosawa was the noir thriller Drunken Angel (1948), in which, although not the lead, his defiant and tubercular yakuza ‘Matsunaga’ electrified domestic audiences in the same way that Marlon Brando would do in America in a couple of years later in The Men and A Streetcar Named Desire. The pair would make fifteen films together, bringing Japanese cinema to the international audience for the first time with Rashomon (1950), which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. This led to a vogue for Japanese movies among discerning Western cinemagoers now tiring of Italian neorealism. In Rashomon, various characters famously provide subjective, alternative and contradictory versions of the same event – the death of a samurai and the assault of his wife – a device that at once looks back to the ambiguity of the European gothic and forward to the ontological uncertainty of the postmodern text. International recognition for both Kurosawa and Mifune was cemented by films like The Seven Samurai (1954), a period drama inspired by John Ford westerns that was in turn remade as the Hollywood western The Magnificent Seven (1960); and Yojimbo (‘The Bodyguard’, 1961), which inaugurated the modern archetype of the itinerant warrior, ‘the man with no name’ – in this case a wandering and solitary Edo Period samurai. Yojimbo was also remade (without permission) by Sergio Leone as the ‘spaghetti western’ A Fist Full of Dollars (1964) starring Clint Eastwood. The Hidden Fortress (1958, again starring Mifune), was a key inspiration for Star Wars, and when George Lucas finally got the chance to make his epic, he hoped Mifune would play either Darth Vader or Obi Wan Kenobi. Kurosawa and Mifune’s productive partnership finally came to an end after a dispute over their last film, Red Beard (1965), and Kurosawa’s increasingly long production schedules. (Red Beard took two years to shoot, during which Mifune was unable to work on any other projects.) Mifune continued to work in both America and Japan, though he turned down the offer to play ‘Tiger Tanaka’ in You Only Live Twice, telling Cinema Magazine ‘Generally speaking, most East–West stories have been a series of clichés. I, for one, have no desire to retell Madame Butterfly.’ He once again caught the world’s attention in 1980 as Lord Toranaga in the American TV miniseries Shōgun, an adaptation of the novel of the same name by James Clavell (a new version of which has just started running on Disney+). In his memoir Something Like An Autobiography (1981), Kurosawa wrote of Mifune:

Mifune had a kind of talent I had never encountered before in the Japanese film world. It was, above all, the speed with which he expressed himself that was astounding. The ordinary Japanese actor might need ten feet of film to get across an impression; Mifune needed only three. The speed of his movements was such that he said in a single action what took ordinary actors three separate movements to express. He put forth everything directly and boldly, and his sense of timing was the keenest I had ever seen in a Japanese actor. And yet with all his quickness, he also had surprisingly fine sensibilities. The Japanese Macbeth

Mifune, one of the greatest actors of the twentieth century, was quite modest about his talent, once telling a journalist, ‘Since I came into the industry very inexperienced, I don’t have any theory of acting. I just had to play my roles my way.’ Of his collaborations with Kurosawa, he said, ‘I have never as an actor done anything that I am proud of other than with him.’ And even though he and Kurosawa were never friends again after Red Beard, the great director also admitted, ‘All the films that I made with Mifune, without him, they would not exist.’

Throne of Blood was the ninth collaboration between Kurosawa and Mifune, following their contemporary drama I Live in Fear (1955), about an aging industrialist who plans to save his extended family (including mistresses and illegitimate children) from the nuclear war he believes inevitable by moving them all to Brazil. Although nowadays viewed as a powerful psychological exploration of the emotional effects of living under a constantly deferred apocalypse, I Live in Fear received mixed reviews and a poor domestic box office, being the first film Kurosawa had ever made that lost money. Their next project, then, returned them to the tried and tested world of samurais and Jidaigeki – period drama – and to a play that Kurosawa loved.

Orson Welles as Macbeth

Kurosawa had originally planned to follow Rashomon with Macbeth, but put the project on hold in deference to Orson Welles’ film version of 1948. He revived it almost a decade later. Throne of Blood was to be the first of three samurai films for Toho, Kurosawa announced in the spring of 1956, to be followed by The Hidden Fortress – the story of two peasants who agree to escort a man and a woman across hostile territory for money, unaware that the man is a general and the woman a princess – and Revenge (later retitled Yojimbo), in which a sardonic rōnin (a masterless samurai) drifts into a small town run by two rival gangs and decides to play both sides off against the middle. Originally, Throne of Blood was to be directed by Ishirō Honda, the director of the original Godzilla (1954), but in the end all three movies were directed by Kurosawa at Toho’s insistence. Kurosawa also saw Throne of Blood as a historic cautionary tale which would balance nicely with his 1952 film Ikiru (‘To Live’, his only film in the 50s not to feature Mifune), in which a terminally ill postwar bureaucrat played by Kurosawa regular Takashi Shimura (the leader of the Seven Samurai) attempts to find meaning in his life by cutting through miles of red tape to help a group of families build a children’s playground. (If this sounds familiar, the film was remade in the UK in 2022 as Living starring Bill Nighy with a screenplay by Kazuo Ishiguro.) Loosely based on Tolstoy’s novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), Ikiru explores the themes of death, family, authority, and complacency; the labyrinthine bureaucracy, like Chancery in Dickens’ Bleak House, intended to create meaningless activity without resolution. The film’s protagonist, Watanabe, breaks the rules in order to make things happen but is quickly forgotten after his death, while his colleagues’ resolve to live with the same level of authenticity that he finally achieved soon revert to type. In Macbeth, of course, such maverick behaviour leads only to murder, guilt, and destruction. Kurosawa also felt that medieval Scotland and Feudal Japan – the Sengoku (‘Warring States’) period – had much in common; politically unstable and routinely violent, with rival warlords and clannish powerbases vying for control of the country, while innocents were forever caught in the middle when swords and armour clashed. The two countries are also geographically similar, both lands of mountains, rugged coastlines, and prehistoric forests hammered by harsh and unforgiving weather.

Throne of Blood was written by Kurosawa and his frequent collaborators Shinobu Hashimoto (Rashomon, Ikiru, The Seven Samurai, I Live in Fear, The Hidden Fortress), Ryūzō Kikushima (Stray Dog, The Hidden Fortress, Yojimbo, Sanjuro), and Hideo Oguni (Ikiru, The Seven Samurai, I Live in Fear, The Hidden Fortress, Sanjuro, Red Beard). Their screenplay eschews the original Shakespeare in favour of dialogue appropriate to samurai (knights) and daimyōs (feudal lords) in the first part of the Edo period, early seventeenth century Japan. Shakespeare’s central themes of loyalty, betrayal, tragedy, witchcraft and the supernatural, and the collapse of moral order however remain intact. The screenwriters also looked to Japanese theatre, using many of the devices of Noh, a traditional form of dance and drama dating back to the fourteenth century or Muromachi period. Noh is the oldest of the three forms of classical Japanese drama, the others being Kabuki, which evolved out of Noh during the Edo period and tends to be more energetic and colourful (western correlatives would be melodrama and music hall), and Bunraku, which uses puppets. Noh is a more formal mode of drama than Kabuki, which is light-hearted and contemporary. Noh traditionally explores spiritual themes like life, death, the afterlife, and the Buddhist doctrine of impermanence, that all existence is ‘transient, evanescent, inconstant.’ Performances are sombre and stylised, using elaborate masks, formalised movement, and subdued music and dance to tell the story. Kabuki is more upbeat, with colourful costumes and make-up, cheerier musical accompaniment, exaggerated movements, and a sense of humour. As Kurosawa, his writers and actors knew, The Tragedie of Macbeth translated perfectly to Noh drama. The Japanese Macbeth

The film’s musical score is also Noh-like, composer Masaru Satô (I Live In Fear, The Hidden Fortess, Yojimbo, Sanjuro) immediately creating an ominous, funerary atmosphere with bamboo drums and flutes, while like Orson Welles’ Macbeth, a wailing winter wind emphasises the bareness of the land around Spider’s Web Castle. Production designer Yoshirô Muraki (who had worked with Kurosawa on I Live in Fear), draws similarly from the Noh stage, his interiors graphic and spare, the paper walls acting like traditional Japanese woodblock and silkscreen prints against which the actors become part of the design. Spider’s Web Castle was also based on Edo period woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e, its wooden exteriors built full size on the slopes of Mount Fuji. As Kurosawa later said, ‘We decided that the main castle set had to be built on the slope of Mount Fuji, not because I wanted to show this mountain but because it has precisely the stunted landscape that I wanted. And it is usually foggy. I had decided that I wanted lots of fog for this film.’ (Fog is another mise-en-scènic device borrowed from Welles’ Macbeth.) Muraki painted the castle walls black to contrast with the bleak environment, and it looms out of the mist like some ancient and terrible monster. Special effects were by Eiji Tsuburaya, best known for his work on the original Godzilla films, and when the trees of Spider’s Web Forest (Kurosawa’s Dunsinane) come to the castle, he created an eerie, swaying mass of leaves and branches in fog, as if endlessly but not quite falling, and lumbering forward as hundreds of suddenly homeless birds invade the castle. It’s difficult not to remember Tsuburaya’s many kaiju movies looking at those ‘spider trees’ moving.

Throne of Blood follows Shakespeare’s Macbeth closely. Macbeth becomes General Taketoki Washizu (Mifune), Banquo is General Yoshiaki Miki (The Seven Samurai’s Minoru Chiaki), Duncan is the daimyō they serve, Lord Kuniharu Tsuzuki (Takamaru Sasaki); Lady Macbeth becomes Lady Asaji Washizu (Isuzu Yamada), and Macduff is General Noriyasu Odagura (Takashi Shimura). The film opens with Washizu and Miki returning to Spider’s Web Castle, Lord Tsuzuki’s seat of power, having successfully put down a rebellion. They become lost in the forest and encounter a ‘witch’ (also translated variously as a ‘monster’ or ‘evil spirit’) spinning an apparently endless silk thread while singing a dirge about the futility of existence. Chieko Naniwa’s witch immediately establishes the film’s Noh credentials. Although Kurosawa could not use Noh masks, his actors wore rigid and heavily made-up, mask-like expressions, and the witch’s powdery white face is locked in a rictus grin as she foretells that Washizu will first become Lord of the Northern Garrison then daimyō, the lord of Spider’s Web Castle, while Miki will become commander of the first fortress and, one day, his son Yoshiteru will be daimyō… The Japanese Macbeth

Toshiro Mifune and Isuzu Yamada

The Noh sensibility continues as Mifune holds his face in contorted snarls and conflicted leers as his wife draws him into the inevitable murder of the visiting daimyō, plotting in a haunted room in which the blood of the previous Lord (who committed suicide) can never be washed away, foreshadowing her later madness. Lady Asaji is the quintessential Noh character, her presence one of porcelain tranquillity, her face frozen and pale, her movements precisely choreographed as she glides through rooms like a ghost, the only sound the rustle of her silk kimono; the delicacy of her movement in stark contrast to the violence of her schemes. Her husband, meanwhile, is edgy and conflicted, yet ambitious and easily manipulated. His movements are therefore a mix of reflective inactivity and explosive eruptions of action. At times, the film feels as if it is being performed on stage in front of the camera. Miki’s ghost at the banquet, for example, eerily luminous, his figure entirely white, like the witch of the forest, is as silent and still as a statue. But these stylised, tableau-like interiors can explode into action and movement, as the theatrical segues beautifully into the cinematographic, validating Kurosawa’s belief that Noh drama could be as gripping and energetic as any movie. The world of the film becomes bigger in exterior scenes such as Washizu and Miki in the forest, firing off arrows on horseback at first believing the disembodied voice of the witch to be an enemy ambush; the riders in the fog, hopelessly lost in the terrible void; or Washizu hacking through the forest once more in search of the witch towards the end of the story, when he will misinterpret her fatal prediction that no harm will come to him until ‘the trees of the Spider’s Web Forest rise against the castle.’ Somehow, in Throne of Blood, the stasis that is key to the Noh performance counterpoints the kineticism of film in harmonious balance. The effect is hypnotic, even watching almost seventy years later, because of Kurosawa’s visual style and Mifune’s powerhouse performance, stylishly supported by Chiaki’s pragmatic Banquo and Yamada’s haunting Lady Macbeth.

Kurosawa parts company with Shakespeare slightly during the film’s climax, dispensing with the witch’s second prediction that ‘No man that’s born of woman / Shall e’er have power upon thee’, and focusing instead on the assault on the castle by the Macduff figure – General Odagura – and the son of Lord Tsuzuki, Kunimaru (Malcolm). Like Macbeth, Washizu believes himself to be invincible, but instead things quickly fall apart. His wife has become more ghostly in madness, obsessively washing imaginary blood from her hands, while a panicking lookout reports that ‘The trees have risen to attack us!’ after Odagura orders his troops to cut branches from the trees to camouflage their numbers. Washizu remains nonetheless defiant, even though he knows his fate is sealed, but unlike Macbeth, his death comes at the hands of his own men, desperate to avoid execution for treason. As Washizu paces the battlements, trying to rally his men with talk of victory, they begin to fire arrows at him. As scores of arrows embed in the walls around him, he frantically slashes them away with his sword, but more and more volleys come, barring his way, and sticking from his armour until the final, fatal shot. The scene is disconcertingly realistic, because it was actually real; only the coup de grâce was a special effect. Just as Kurosawa insisted the crew wait until real fog descended on Mount Fuji to shoot the scene in which Washizu and Miki are lost after seeing the witch, his commitment to realism included the use of real archers firing real arrows at Mifune during the film’s climax. Being essentially a method actor, and descended from samurai stock on his mother’s side, Mifune could hardly refuse. He therefore used the movement of his sword arm to indicate to the archers which way he was going while the scene and the arrows were shot, so as not to be hit by accident. Knowing this makes viewing the scene particularly edgy; the exaggerated horror on Mifune’s face was probably real as well.

Given the relative closeness of the two postwar movies, it’s quite productive to watch Throne of Blood alongside Orson Welles’ Macbeth. Both are stark, expressionistic movies, shot in black and white, making much use of shadows and fog. Both are the passion projects of brilliant auteur directors, with brooding, intense turns by the central cast, Mifune and Yamada, and Orson Welles and Jeanette Nolan as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth. Welles’ dreamlike and theatrical production feels like the herald of Throne of Blood, and there are certainly stylistic features in common, for instance the bold chiaroscuro contrasts between light and dark favoured by both directors, the spooky wind whistling through both soundtracks, the mist, the screeching birds, and the eerie movement of the trees of Dunsinane. Sadly, Welles’ low budget and 23 day schedule for Republic Pictures did not let him make the film he wanted (he had visualised ‘a perfect cross between Wuthering Heights and Bride of Frankenstein’) and though his haunting and idiosyncratic Macbeth is better than his contemporary critics and the film histories allow, it is oddly Kurosawa’s interpretation that is hailed as the better film version of the play, despite the lack of original dialogue. The critical consensus is that Kurosawa’s visual style and Mifune and Yamada’s performances justify the absence of Shakespeare’s words.

Akira Kurosawa

The Japanese Macbeth

Throne of Blood was a commercial success in Japan, becoming the second highest grossing film of 1957, losing out to Kunio Watanabe’s Meiji tennô to nichiro daisenso (‘Emperor Meiji and the Great Russo-Japanese War’), a film that no-one now remembers, though there were some grumbles that the Noh references were ‘old fashioned.’ In the UK, Throne of Blood was the first film to be screened at the 1st BFI London Film Festival in October, 1957. After the screening, Kurosawa attended a party at the house of the film critic and travel writer Dilys Powell where he met Laurence Olivier and his wife Vivien Leigh, who were at that point planning their own film version of Macbeth. Olivier was never able to raise the money for this project, and his Macbeth was never made although, tantalisingly, his original screenplay was discovered in the British Library ten years ago. Olivier praised Kurosawa’s climax scene and imagined his Macbeth as a ‘blood-bolted and murky production.’ Had he made it, we would have likely seen the influence of Throne of Blood.

Kurosawa would go on to make two more Shakespearian adaptations. In the noirish The Bad Sleep Well (1960), Mifune plays a young man who gets a job in a corrupt postwar company in order to expose the men responsible for the death of his father in a loose update of Hamlet. Kurosawa (but not Mifune) returned to the bard for his final masterpiece, Ran (1985), a samurai epic based on King Lear that is a joy to behold. He made three more films after Ran, dying on September 6, 1998, eight months after Mifune. Writing this piece now, as someone who lived in Japan for several years, I still find it hard to believe that the world continues to turn without these two men in it. But we do have their films, with Mifune’s ghost emoting as wildly as ever. He was the Japanese Macbeth, and completely irreplaceable. And if a Shakespeare film without any Shakespeare doesn’t appeal, try watching Throne of Blood in the original Japanese, without subtitles, and just let Shakespeare’s iconic words come to you:

Henceforth be earls, the first that ever Scotland

In such an honor named. What’s more to do,

Which would be planted newly with the time,

As calling home our exiled friends abroad

That fled the snares of watchful tyranny,

Producing forth the cruel ministers

Of this dead butcher and his fiend-like queen

(Who, as ’tis thought, by self and violent hands,

Took off her life)—this, and what needful else

That calls upon us, by the grace of grace,

We will perform in measure, time, and place.

So thanks to all at once and to each one,

Whom we invite to see us crowned at Scone.

That’s how I do it.

Main image: Akira Kubo, Chieko Naniwa as Old Ghost and Toshiro Mifune. Credit: Masheter Movie Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Vintage Film Poster for Throne of Blood (1957). Credit: Sam Kovak / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Toshiro Mifune and Isuzu Yamada. Credit: Photo 12 / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Orson Welles as Macbeth (1948) Credit: Moviestore Collection Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Cartoon of Akira Kurosawa Credit: Helmut Kruse / Alamy Stock Photo

Our paperback edition of Macbeth can be found here: Macbeth

For more information on Kurosawa’s life and works, visit: The Akira Kurosawa Community

The Japanese Macbeth

The Japanese Macbeth

The Japanese Macbeth

The Japanese Macbeth

The Japanese Macbeth

The Japanese Macbeth

The Japanese Macbeth

The Japanese Macbeth

Books associated with this article

Macbeth (Collector’s Edition)

William Shakespeare