Shakespeare’s Sonnets

‘Not marble, nor the gilded monuments Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme’: Sally Minogue looks at the appeal of Shakespeare’s Sonnets at a time of lockdown.

When I do count the clock that tells the time

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night…

(first lines of Sonnet 12)

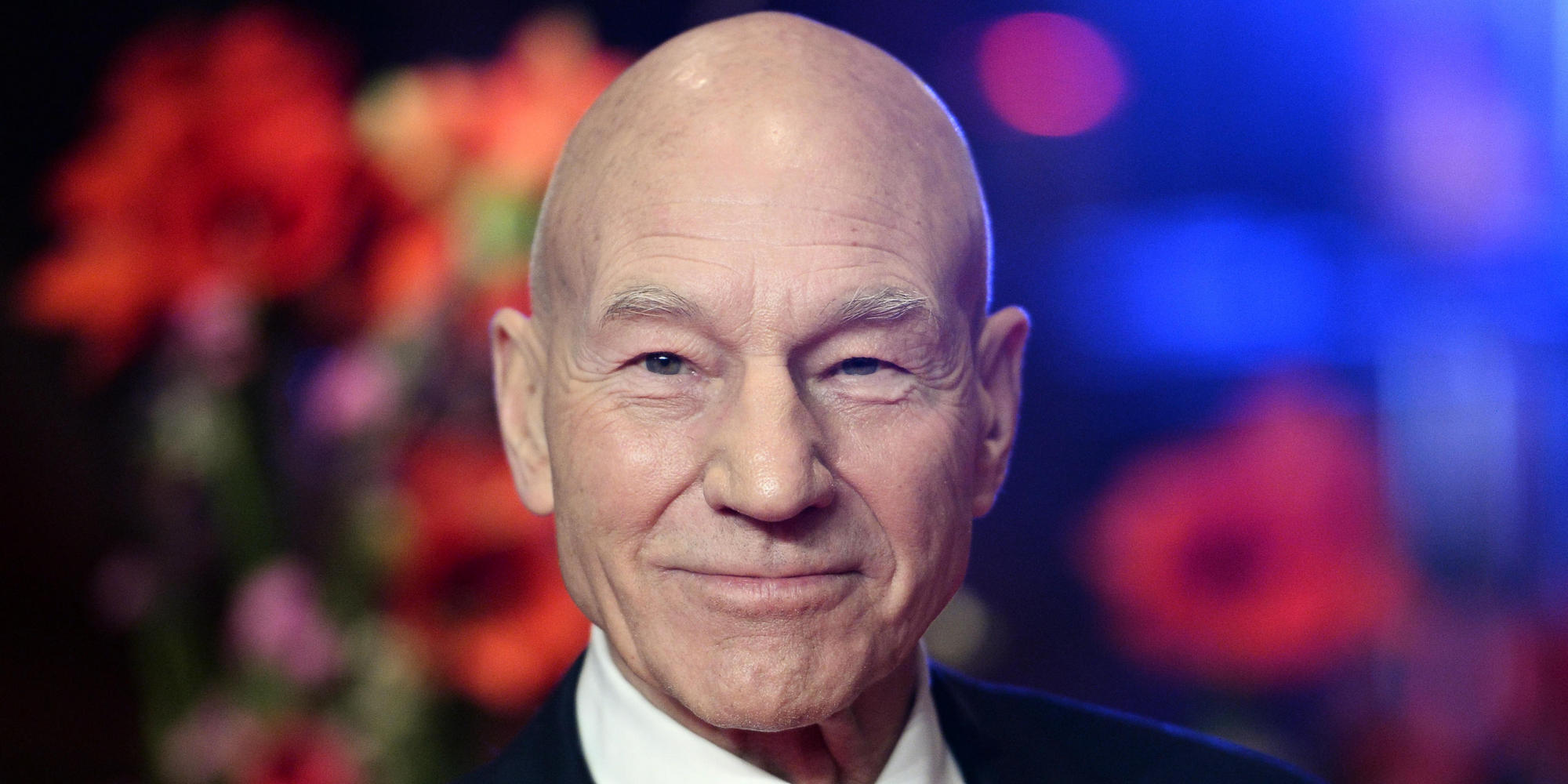

Sir Patrick Stewart paused when he got to this one in his lockdown readings of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, saying simply, while looking us straight in the eye: “ I hope you’re ready for this.” He was acknowledging the fact that just now we’re all counting the clock that tells the time, and not in the daily, quotidian sense. Suddenly, we’re dealing with genuine horror. And while we flinch from that – the threat of unlooked-for and senseless death – we’re also called on to withdraw from our closest human contacts, the very ones that we instinctively seek comfort from, and want to give comfort to. There’s not much help at the end of the poem either:

And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him when he takes you hence.

Well, ok – a little comfort. If you’ve got children (breed), they may outlive your death, and carry something of you forward with them. But the inexorable sweep of ‘Time’s scythe’ will, of course, in time take them too. And onwards, in an endless harvest.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets can be bleak, as here, so it’s particularly interesting that so many people have turned to Sir Patrick Stewart’s readings of them, which have become a social media event. He began on March 21st on Twitter, as most people entered lockdown, and his posts of a sonnet a day have been enormously, extraordinarily popular, on a whole range of social media platforms. Some of this can be attributed to the fame of this actor over a range of age groups, through the blockbuster film as well as Shakespearean theatre, and all hail to him for calling in and on his wide audience with such difficult material. These sonnets are not easy. Their language is Elizabethan, full of punning, often using the sense of a word unfamiliar to a modern audience; the syntax can be complicated, cutting across the demandingly tight form of the sonnet, resisting the flow of normal human speech. The conceits – the complicated conventions and metaphors that run through the poems – have to be learnt and understood as we progress through our reading, though gradually we are rewarded with a depth of understanding as that knowledge builds.

Stewart, self-deprecatingly, admits all this difficulty. A few times he’s said bluntly, “This one was too hard, so I’m leaving it out”, or he’ll concede after he’s finished reading – “Complex!”. And he’ll also occasionally say that he’s not prepared to read a poem because “I find this offensive”. (I’d like to hear more about why.) So this is a very personal presentation of the Sonnets, but one which allows us as readers and audience to make our own similar decisions. “This one’s hard to fathom; that one I don’t care for.” Stewart will even stop part way through his reading and start again – an unusually modest thing in an actor. He could, after all, have hidden all that by starting the video again and presenting it without flaws. In one case, he confesses that he was disappointed with the reading (of Sonnet 29) on the previous day (“I can do better”), and gives us a second version. Thus he leads his audience in, and they are ready to listen, forgivingly.

The pleasures of Stewart’s reading aside, why are these sonnets from over 400 years ago so powerful just now? Let’s look at a few of them and try to answer that. Stewart prefaced the full sequence of sonnets with one taken out of order, Sonnet 116, ‘Let me not to the marriage of true minds’. Later, in sequence, he reads Sonnet 18, ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ Both are well known, for good reasons. They are benign, optimistic, loving, full of faith in the human enterprise – the opposite of Sonnet 12 with which I started. ‘Let me not’ is a poem in celebration of human love, and it has no dark shadows or doubtings: love ‘is an ever-fixed mark, / That looks on tempests and is never shaken’. This is a love that ‘bears it out even to the edge of doom.’ The emphasis is all on steadfastness, unshakeably. Whatever may come to challenge us, true love – true in the sense of unflawed, true like a straight piece of wood, true as in faithful forever – will be a match for it. Not only do we need to hear such a testament in these dark times, but it is indeed the case that this crisis has stripped away trivial things from our minds and brought to the fore the power of our feelings for those we hold most dear. In part, this is because it is precisely those people that we may be most completely separated from; this is a time where love is expressed by absence and commitment by abnegation.

Sonnet 18, ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’, takes us from that generalised idealizing of love in the abstract to a close-up of the loved person. In answer to the opening question comes back the swift, hyperbolic, typical lover’s reply: ‘Thou art more lovely and more temperate’. The whole poem continues the conceit that the beautiful beloved outstrips the beauty of the natural world, so comparisons are pointless. Of course, in making that claim he is making comparisons throughout, with the beloved always the superior. And here, even Death has no dominion: ‘thy eternal summer shall not fade’. To resolve this apparent contradiction, Shakespeare introduces a key theme of these sonnets: the poem itself is the talisman against mortality. The young man (and towards the end of the sequence, the woman) that he loves will inevitably die. But the lines that preserve his beauty, and express the powerful feelings he has engendered in the poet, will not die: the evidence is there in the lines we are even now reading. If Shakespeare often loses his trust in his lover, and sometimes even in love itself, he never falters in his belief in the immortality of his own poetry. His best lines, his most intricate conceits, his most telling rhymes, and often his final couplet, are given over to that. Sonnet 18 ends thus:

So long as men can breathe, and eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

The rhyming of ‘see’ and ‘thee’ reminds us that we have indeed just ‘seen’ the young man; the balanced repetition of ‘So long’ at the start of both lines emphasises the eternal element of the human, for though individual bodies die, the human race continues, to breathe, to see, to read. And we as readers, breathe and see as we read. The truth of those last lines is ungainsayable, and the several sonnets which celebrate the immortality of ‘black ink’ on the page in their final couplet release the reader into a hopeful imaginative universe.

The third poem of this kind, Sonnet 29, ends not on the power of art but the simple power of love itself – no need even to look to the immortality of the poem for comfort. This sonnet begins more darkly but then progresses to sweetness.

When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself and curse my fate…

Well, yes, we’ve all done that, and he goes on doing it for four more lines. Then at the point in the poem which traditionally allows for a change of tone or a twist of thought or feeling, after the first eight lines, Shakespeare turns upon his own distress, with the clarion call of the conjunction ‘Yet’:

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

Like to the lark at break of day, arising

From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate;

This brilliant lyric burst, mimicking the lark it so gloriously depicts, lifts us away from the mire of the octet, and suddenly we are ‘at heaven’s gate’. In fourteen lines, we have moved from extravagant despair to quiet, profound joy:

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

I have concentrated here on those sonnets which bring solace, reminding us of the depth of human love and the immortal power of art to express it. But the comfortless and forbidding Sonnet 12 with which I began has been one of the most popular of Stewart’s readings; on Twitter, it has received 444,800 views. There’s an appetite there for complex, challenging poetry which confronts us with the inevitability of our own end and the remorseless swish of ‘Time’s scythe’, which has suddenly been sharpened.

I’m not always a fan of the way Sir Patrick interprets and reads some of the sonnets – here, too hesitant and speculative, there, too actorly. Well, he is, after all, an actor. It was, therefore, all the more touching when, as he started Sonnet 23: ‘As an unperfect actor on the stage…’, he wrongly read it as ‘imperfect’, and, as himself an ‘unperfect actor’, immediately stopped and started again, to get it right. It is this, I think, that has made his daily readings so appealing to a wide audience, that they are engagingly human. Even though the flat plane of the screen, we see and hear a human being speaking to other human beings, through a consummate poetic voice which is also human, and spans the centuries to speak to our current human condition.

But let’s not end on too serious a note. Now is a time when we need fun more than ever, and there’s plenty of that in the sonnets. Look out for Sonnet 130 in which Shakespeare makes mischief with the standard ways in which his fellow sonneteers lauded female beauty – ‘My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun’. And look up Sonnet 20, which Stewart left out, explaining that he didn’t want to read it because it made him uncomfortable in the way it talked about women. I’m sorry we didn’t get that reading. It’s one of Shakespeare’s most verbally playful poems; nothing in it is really serious, including the view of women. And now let’s admit it, finally – one of the reasons we keep visiting Sir Patrick on Twitter is to see his eclectic range of tee-shirts and the equally entertaining array of views of his interior décor. Some truths remain eternal, even in lockdown.

Sir Patrick Stewart’s readings so far can be found in their original incarnations on Twitter @SirPatStew, and elsewhere online.

My title is taken from the opening lines of Sonnet 55. My brief quotation referring to ‘black ink’ is taken from Sonnet 65.

Image: Patrick Stewart DPA Picture Alliance / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article