Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: A journey of laughter and tears

David Stuart Davies looks at Twelfth Night, the ever-popular comedy with a darker side.

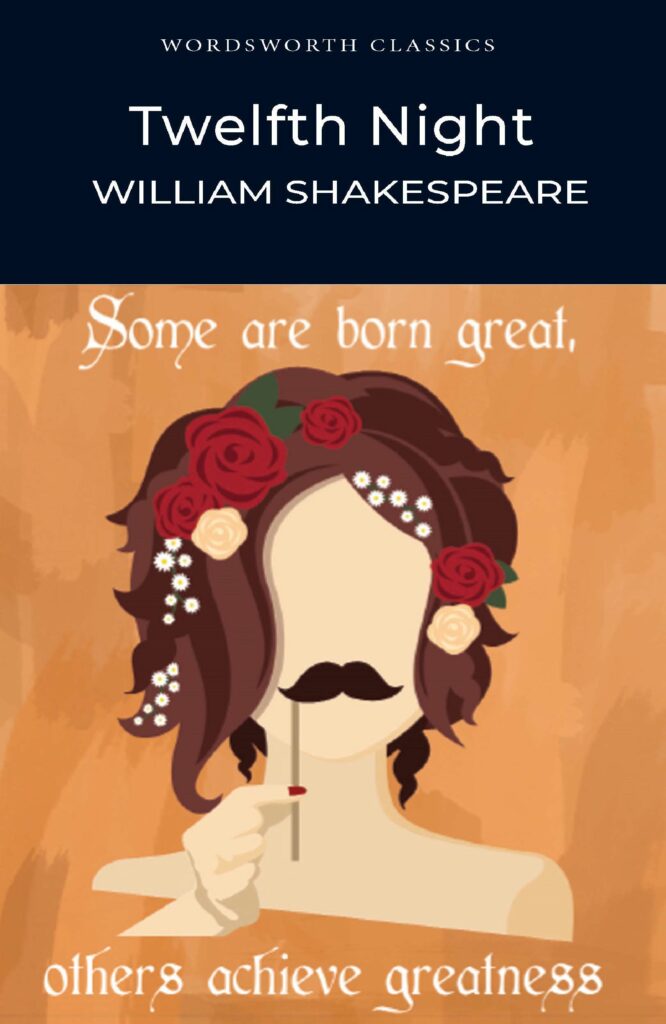

‘Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.’

Malvolio

One of the remarkable talents that Shakespeare possessed was his ability to introduce moments of tragedy and darkness into his comedies and elements of comedy and levity into his tragedies.

Well, life is like that, the playwright seems to say: a journey of laughter and tears. These darker elements add a sharper edge to the comedy, demonstrating how fragile the line is between farce and tragedy.

A fine example of this use of light and shade is found in Twelfth Night and in particular exemplified in the character of Malvolio. He is presented as the epitome of the puritanical, pompous, arrogant self-aggrandising fellow who is riding for a fall – and fall he does. His undoing occurs in the wonderfully comic cross-gartered scene where he has been misled to think that his employer, the ‘rich countess’ Olivia, is attracted to him romantically. He is tricked into believing that she wishes him to smile copiously and wear garish yellow stockings with cross garters. Olivia is in mourning for her brother’s death and therefore finds smiling offensive, and yellow is ‘a colour she abhors, and cross garters a fashion she detests.’

The fellow has been well and truly set up. His behaviour and attire are his undoing. Malvolio’s comic downfall is a result of his officiousness and preening and we the audience, as well as characters in the play, are delighted and amused at his foolishness and his spectacular fall from grace. His comeuppance is something we have desired and now relish. But then events go too far and the frivolity fades and cruelty replaces it. Malvolio is imprisoned for being a supposed lunatic and is visited by Feste, the clown in the guise of ‘Sir Topas the curate,’ and torments Malvolio by making him swear to heretical texts. Rather than being merely mocked for his pretentiousness, he is crushed and degraded.

What began as a joke turns into vindictive persecution. At the end of the play, Malvolio is a broken man and vows, ‘I’ll be reveng’d on the whole pack of you’ for his public humiliation. Olivia acknowledges that he has ‘been most notoriously abused.’ Now we feel sympathy for the character, such is the cunning subtlety of Shakespeare’s writing. His exit strikes a jarring note indicating that Malvolio has no real place in the anarchic, undisciplined milieu of Olivia’s household, suggesting that, perhaps, even in the best of worlds where everyone eventually achieves a kind of happy contentment, someone must suffer.

Having said all that, the main thrust of the play relies on comedy and romantic complications. It was written around 1600-1601 as a post-Christmas entertainment – hence the title, although Samuel Pepys grumbled at what he perceived was the title’s irrelevance to the plot. He referred to it as ‘a silly play, and not related at all to the name or the day.’ Pepys was not alone in disliking the title: King Charles I’s Master of the Revels re-christened it Malvolio.

The play is set in the enchanted land of Illyria and centres on the twins Viola and Sebastian, who are separated in a shipwreck. Viola, disguised as a boy, falls in love with Orsino, the Duke of Ilyria, who in turn is smitten with Olivia. Upon meeting Viola, Olivia falls for her thinking that she is a man. This gender-bending cross-dressing confusion with witty misunderstandings adds much spice and frivolity to the narrative, but one other strand of the comedy is tinged with similar darkness to that of the Malvolio scenario. This involves Sir Toby Belch and Sir Andrew Aguecheek, two knights who behave quite badly, indulging themselves in drinking and revelry, thus disturbing the peace of Olivia’s house where they are guests. It is this that prompts Malvolio to chastise them, quite rightly for their unruly behaviour. Sir Toby famously replies to Malvolio’s censure, ‘Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?’ and so sets about his cruel revenge which involves proving that Malvolio is mad and needs to be locked up. This harsh ploy reveals an ambiguous mix of high spirits and vicious cunning in Belch’s character.

This unpleasant trait is demonstrated further by his cavalier and underhand treatment of his companion, the feeble-minded Sir Andrew. Not only does Sir Toby take advantage of Sir Andrew’s riches, pocketing great sums for himself, but for his own amusement, he goads the foolish fellow into duelling with Cesario who is in fact Viola disguised as a young man. Sir Toby does not seem to care if his friend is injured in this fray as long as he is entertained by the spectacle.

Sir Toby Belch may, as his name suggests, be a lively drunken roisterer but Shakespeare clearly intends him to be seen as possessing a complex nature: a jolly fellow on the surface but one with a cold heart beneath. For example, while happy to take advantage of Olivia’s hospitality, Belch shows no sensitivity or sympathy for his niece in mourning the loss of her brother:

‘What a plague means my niece to take the death of her brother thus? I’m sure care’s an enemy to life.’ This brusque statement raises the question of how far the audience is expected to sympathise with Sir Toby. Is his criticism of his niece a justified statement of the old truism that ‘life must go on’, or an insensitive blunder by a hungover old drunkard? The question effectively epitomises the dual nature of the roguish knight.

The play was adapted for the movie screen in 1996, directed by Trevor Nunn, and featuring an all-star cast: Malvolio was played by Nigel Hawthorne, with Mel Smith as Sir Toby and Andrew Aguecheek by Richard E. Grant.

The setting was moved from its original Elizabethan period to the late 19th century, with the characters wearing uniforms that evoke the Austro-Hungarian Empire. While not necessarily pleasing the Shakespeare purists, this change clearly demonstrated the durability of the playwright’s storytelling, which transcends time and place.

Books associated with this article