David Stuart Davies looks at The Awakening

David Stuart Davies looks at Kate Chopin’s influential novel, first published in 1899.

‘The Awakening is a metaphor for accessing not only the unfamiliar part of one’s consciousness but the buried truth of our society…’

Claire Vaye Watkins

It is interesting to note how many strong independent women feature in novels of the Nineteenth Century: Jane Eyre (Charlotte Brontë), Bathsheba Everdene (Far from the Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy), Catherine Sloper, (Washington Square, Henry James), Isabel Archer (Portrait of a Lady, Henry James) and Jo March (Little Women) to name a few. To this illustrious list one must add Edna Pontellier, the heroine of Kate Chopin’s novel The Awakening. Although both character and author are less well known than those already mentioned, this character has recently been discovered by discerning readers and championed because of Chopin’s concerns regarding the freedom of women which foreshadowed later feminist literary themes and movements of female emancipation.

American writer Kate Chopin was born Katherine O’Flaherty in 1850 into a prominent St Louis family. At the age of twenty she married Oscar Chopin and moved to his native New Orleans in Louisiana. Having read widely as a girl, she only began writing after the early death of her husband in 1882. Her first novel At Fault was unsuccessful but she was later acclaimed for her finely crafted short stories, which focused on the Creole and Cajun people she had observed in the American South.

It was in 1899 that she published her second novel The Awakening, originally titled A Solitary Soul, a strikingly modern and controversial tale concerning the sexual and artistic awakening of a young woman who reclaims her own individuality, refusing to be defined by her roles of wife and mother. Throwing off what she considers as these shackles, she abandons her family to forge a new independent life for herself. Critic Willa Cather has suggested that Edna in some respects can be compared with Flaubert’s Emma Bovary in that both women are caught in a dull marriage and dream of adventure and idealized romantic love.

As Cather observes, ‘she demands more romance out of life than God ever put into it. Mr G. Bernard Shaw would say that they are victims of the over idealization of love.’

One of the symbols used by the author in the novel is that of the sea. For Edna, the sea serves as a source of empowerment and a place of refuge. Edna’s first solo swim marks a critical moment for her awakening. In learning to swim, she conquers her fears and takes control of her body and her actions. She effectively realizes that she has the power to be independent:

‘A feeling of exultation overtook her, as if some power of significant import had been given her to control the working of her body and her soul. She grew daring and reckless, overestimating her strength. She wanted to swim far out, where no woman had swum before.’

The book was roundly condemned on its publication for its sexual frankness and its portrayal of an interracial marriage. Although never technically banned, the novel was censored as it was considered immoral not only for its frank descriptions of female desire but also for the presentation of a woman who rebelled against established gender roles. These are criticisms which were innate in the strait-laced period in which it was written. As a result, the book quickly went out of print for more than fifty years.

Chopin’s love and admiration of the writings of Guy De Maupassant, reflected in the structure and realism of her own short stories, is also present in The Awakening, as a homage to the French writer. She applied his naturalistic approach and style to the creation of her narrative, which gives a perceptive focus on the inner workings and emotional motives that control human behaviour and the influences of the complexities of social structures. Chopin declined to condemn her heroine when she abandons her husband and children in order to follow her fragile dream. Critics were unsettled by this rejection of social norms and many reviled the book as a result. One such comment from the review in the Chicago Times Herald, typical of many contemporary attitudes to the novel, stated, ‘it was not necessary for a writer of so great refinement and poetic grace to enter the overworked field of sex-fiction’. However, when Chopin’s novel was rediscovered in the 1950s, critics were struck by the beauty of its writing and modern sensibility.

The Awakening was the basis for the film, The End of August (1982) starring Sally Sharp as Edna and directed by Bob Grahame. Sadly, as the following review from Time Out explains, the movie failed to deal with the nuances and subtleties of Chopin’s writing: ‘Regrettably the film finds no satisfactory substitute for reflective insights into the female mind, condemning it to a two-dimensional existence and inadvertently relegating Chopin’s work to the genre of ‘local colourist’ from which she endeavoured to escape. A potboiler.’

There was another attempt to bring the novel to the big screen in 1991. Retitled Grand Isle, the film starred Kelly McGinnis as Edna. Time Out was no more enthusiastic about this version, calling it ‘soporific’, adding that, ‘ Thanks to director Mary Lambert’s inept direction, there’s no erotic charge and the liberating ideas that are so strong in the book are lost amid the frocks and period treatment.’

These two reviews clearly illustrate the problem of trying to bring this sensitive and intellectually as well as emotionally satisfying novel to the screen. So much of the drama is embedded in the motive, aspirations and effects Edna’s actions have upon herself and her family, elements that are difficult to illustrate in a powerful form visually. As a result, such a venture is inevitably doomed. The power, beauty and insights are held tightly within the novel’s elegant pages.

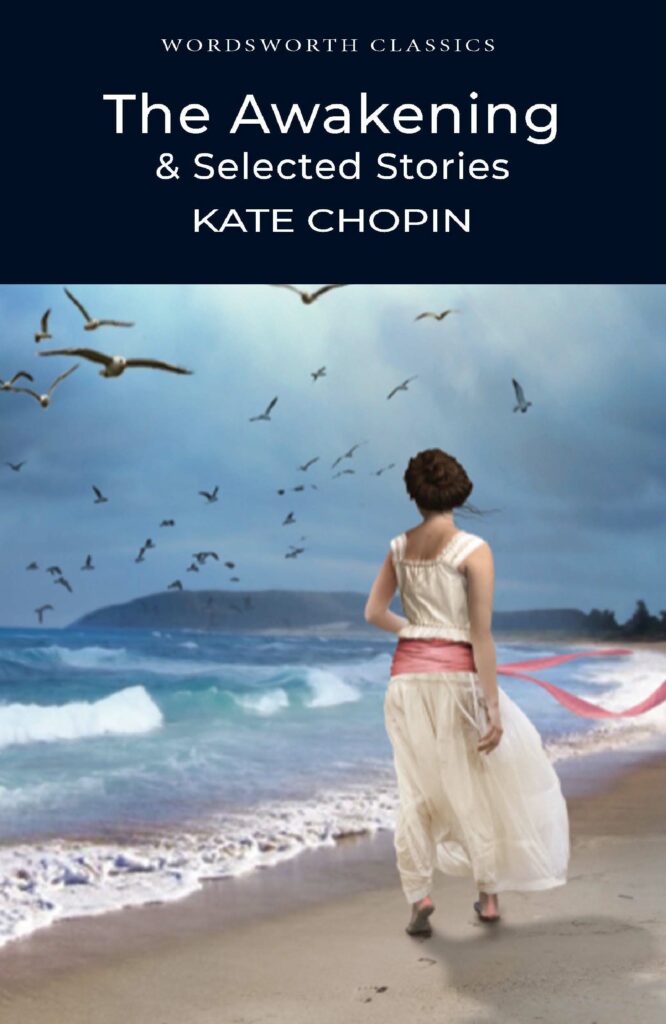

Image: Beach at Grand Isle, Louisiana Credit: Jennifer Maxwell / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article