When Poe Met Dickens

In the United States, one of the first – if not the first – critics to discover the talented new British author Charles Dickens was Edgar Allan Poe. Poe reviewed Dickens’ first book, Sketches by ‘Boz’ in the June 1836 number of the Southern Literary Messenger, the year it was published in London by John Macrone. Though British readers were already acquainted with ‘Boz’ through his humorous sketches in several newspapers, he was unknown in the US and, indeed, to Poe, who wrote, ‘we know nothing more than that he is a far more pungent, more witty, and better disciplined writer of sly articles, than nine-tenths of the Magazine writers in Great Britain.’ Poe concluded by ‘strongly recommending’ ‘Boz’ to his readers. A couple of years later, by which time ‘Boz’ had a name, Poe wrote in Burton’s Magazine: ‘Charles Dickens is no ordinary man, and his writings must unquestionably live.’ When Poe met Dickens

In Graham’s Magazine, Poe also reviewed Master Humphery’s Clock, Dickens’ short-lived weekly periodical published from April 1840 to December 1841, in which his novels Barnaby Rudge and The Old Curiosity Shop were serialised, alongside the ‘Master Humphery’ stories. For Poe, one story stood out in particular:

The narrative of ‘The Bowyer,’ as well as of ‘John Podgers,’ is not altogether worthy of Mr. Dickens. They were probably sent to press to supply a demand for copy … But the ‘Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second’ is a paper of remarkable power, truly original in conception, and worked out with great ability.

This is interesting. Dickens’ ‘Confession Found in a Prison in the Time of Charles the Second’ is an eerie story related in the first person by a retired seventeenth-century soldier. The tone is immediately brooding and morbid:

This is the last night I have to live, and I will set down the naked truth without disguise. I was never a brave man, and had always been from my childhood of a secret, sullen, distrustful nature. I speak of myself as if I had passed from the world; for while I write this, my grave is digging, and my name is written in the black-book of death.

The soldier tells of how he and his wife adopted the young orphan son of his brother, and of how he felt himself becoming ‘haunted’ by the child’s gaze, which reminds him of the boy’s dead mother, with whom he had a troubled history:

I can scarcely fix the date when the feeling first came upon me; but I soon began to be uneasy when this child was by. I never roused myself from some moody train of thought but I marked him looking at me; not with mere childish wonder, but with something of the purpose and meaning that I had so often noted in his mother. It was no effort of my fancy, founded on close resemblance of feature and expression. I never could look the boy down. He feared me, but seemed by some instinct to despise me while he did so; and even when he drew back beneath my gaze — as he would when we were alone, to get nearer to the door — he would keep his bright eyes upon me still. When Poe met Dickens

The soldier becomes more obsessed with the boy’s gaze until he finally murders him and hides the body in a newly planted part of the family garden. Dickens does not dwell on the murder, instead the horror of the tale is the narrator’s descent into madness, first plotting the murder then his fixation with the hidden grave, which he watches compulsively for any signs that might give him away. On the fourth day, the soldier is visited by an old friend with whom he served and another officer he does not know. They sit in the garden, and the narrator places his chair over the grave. He then imagines the unknown guest is staring at the spot. To make matters worse, the garden is invaded by a pair of bloodhounds that have slipped their leads and are clearly aware something’s in the ground. Finally, ‘I fell upon my knees, and with chattering teeth confessed the truth, and prayed to be forgiven.’

The Tell-Tale Heart

The similarities between Dickens’ ‘Confession’ and Poe’s 1843 story ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ are unmistakable. Both stories are deep confessional dives into disintegrating minds, with each narrator madly obsessed by another person’s eye, who they ultimately murder. The protagonists then conceal the bodies but become fixated by the graves, and both end up sitting over the burial sites talking to third parties until their own delusions force them to confess. These stories both signal the shifting thematic of the gothic epiphany in the nineteenth century, the threat moving from something external – some sort of mad monk, ghostly nun, or villainous aristocrat – to something internal and uncanny, insanity itself. When Poe met Dickens

Given the endless pressure of producing copy to deadlines to make a living, it was not without precedent for Poe to rework an idea by another author. We tend to forgive him because he invariably improved on the original. We certainly know that he raided several Regency tales of terror, as his satirical piece ‘How to Write a Blackwood Article’ attests. There are echoes of John Galt’s ‘The Buried Alive’ in ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, while William Maginn’s ‘The Man in the Bell’ and William Mudford’s ‘The Iron Shroud’ collectively form the basis for ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’. As William Faulkner is said to have observed (though this line has also been attributed to T.S. Eliot, Stravinsky, and Picasso): ‘immature artists copy, great artists steal.’

Poe also reviewed the first four chapters of Barnaby Rudge for Graham’s Magazine. He predicted the serial’s climax, and was gratified to discover he had been right when he later reviewed the complete novel. Set around the Gordon Riots of 1780, Barnaby Rudge is one of Dickens’ more neglected novels nowadays, an early work quickly eclipsed by A Christmas Carol, which followed it. Like Oliver Twist, it also sits in the ‘Newgate’ tradition, which was a label Dickens himself was keen to avoid. Although not the hero, the simple-minded and ‘innocent’ Barnaby Rudge of the title drifts in and out of the narrative accompanied by a pet raven called ‘Grip’. Barnaby talks to Grip, who in turn expressively croaks:

The raven gave a short, comfortable, confidential kind of croak;—a most expressive croak, which seemed to say, ‘You needn’t let these fellows into our secrets. We understand each other. It’s all right.’

Grip has also learnt a few human words and phrases, most notable ‘Never say die!’ and ‘Nobody!’ Poe loved Grip, and speculated on the possibility of expanding its role within the narrative:

The raven, too, intensely amusing as it is, might have been made more than we see it, a portion of the conception of the fantastic Barnaby. Its croaking might have been prophetically heard in the course of the drama. Its character might have performed, in regard to that of the idiot, much the same part as does, in music, the accompaniment in respect to the air. Each might have been distinct. Each might have differed remarkably from the other. Yet between them there might have been wrought an analogical resemblance, and although each might have existed apart, they might have formed together a whole which would have been imperfect in the absence of either. When Poe met Dickens

Hold that thought.

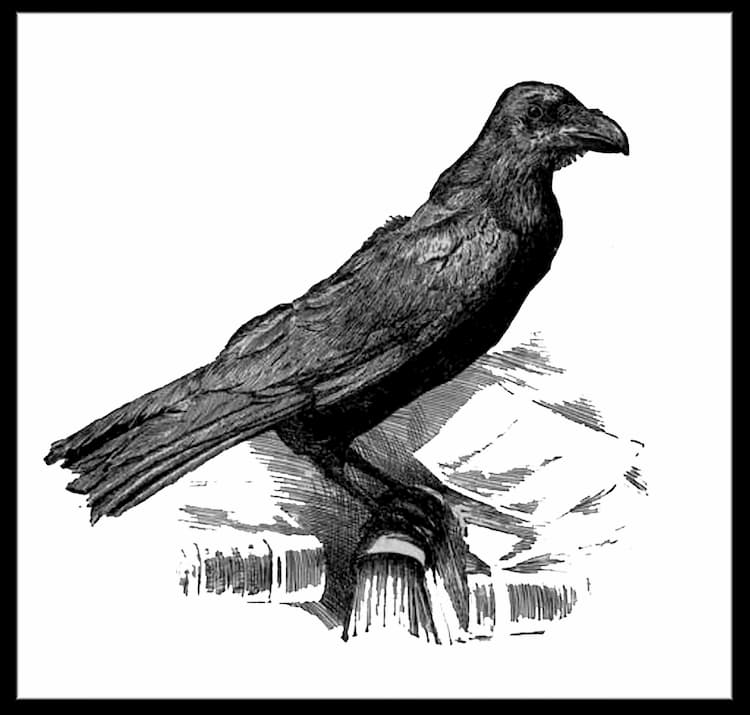

Barnaby Rudge and ‘Grip’

Barnaby’s ‘Grip’ was based on Dickens’ pet raven, which was also called ‘Grip’. The original Grip lived with the Dickens family in Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone, and was given the run of the house like a cat or a dog. She could speak several phrases – her favourite being ‘Halloa old girl!’ – liked to bury cheese, potatoes and coins in the garden, and had a tendency to bite the servants and the children. She also terrorised the family dog. Dickens adored the irascible creature, once writing to the artist Daniel Maclise, ‘I love nobody here but the Raven, and I only love him because he seems to have no feeling in common with anybody.’ It made sense, then, that she would become a part of one of his novels. As Dickens wrote to his friend George Cattermole, ‘Barnaby being an idiot, my notion is to have him always in company with a pet raven, who is immeasurably more knowing than himself. To this end I have been studying my bird, and think I could make a very queer character of him.’

After the bird bit one of the children, Dickens’ wife Kate insisted that she be removed from the main house. She therefore took up residence in the carriage house. When the stable was painted in 1840, Grip drank some paint left behind by the workmen and tragically died of lead poisoning. ‘The children seem rather glad of it,’ Dickens confessed to Maclise. Dickens had poor old Grip stuffed and mounted in a glass case which he hung above his desk, so the raven could look down on him as he wrote. This was not unusual for the novelist. He already had a letter-opener made from the paw of his late cat, Bob.

Dickens first visited the United States in 1842 with Kate, arriving in Boston on the RMS Britannia on January 22. This is the visit described in his travelogue American Notes for General Circulation. Dickens gave a series of lectures, during which he pointedly raised the question of international copyright laws and the pirating of his novels in the US. (In 1834, the US Supreme Court had ruled that an author did not have a common law right to control reproduction following the first publication of the work. The US market was therefore flooded with unlicensed but perfectly legal editions that made money only for their publishers.) In New York, he persuaded a group of writers, including Washington Irving, to sign a petition on the matter for him to present to Congress. The press were, however, unsympathetic, seeing what he called ‘piracy’ as honest American free enterprise. Dickens, they said, should be grateful for his warm welcome (he was mobbed by admirers wherever he went) and international fame.

When it was announced in the press in March that Dickens had arrived in Philadelphia to give a lecture and was staying at the United States Hotel, Poe, who was living there at the time, made contact. He sent Dickens his two-volume collection of short stories, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840), and a letter requesting a meeting. Dickens promptly and enthusiastically replied:

My Dear Sir, — I shall be very glad to see you whenever you will do me the favor to call. I think I am more likely to be in the way between half-past eleven and twelve, than at any other time. I have glanced over the books you have been so kind as to send me, and more particularly at the papers to which you called my attention. I have the greater pleasure in expressing my desire to see you on this account. Apropos of the “construction” of “Caleb Williams,” do you know that Godwin wrote it backwards, — the last volume first, — and that when he had produced the hunting down of Caleb, and the catastrophe, he waited for months, casting about for a means of accounting for what he had done? When Poe met Dickens

A terrible name-dropper, Poe would later open his seminal essay The Philosophy of Composition (1846) by quoting Dickens’ comment to him on Godwin’s writing process and then developing it as his first point, suggesting that he and Dickens knew each other quite well, which was a bit of a reach. As well as being a genuine admirer of Dickens, Poe was certainly hoping to court him as a heavyweight literary contact in Britain, and although we only have one side of the written dialogue, it’s clear from Dickens’ remarks that Poe was trying to showcase his abilities as both an author and a critic.

Charles Dickens’ pet raven, ‘Grip’

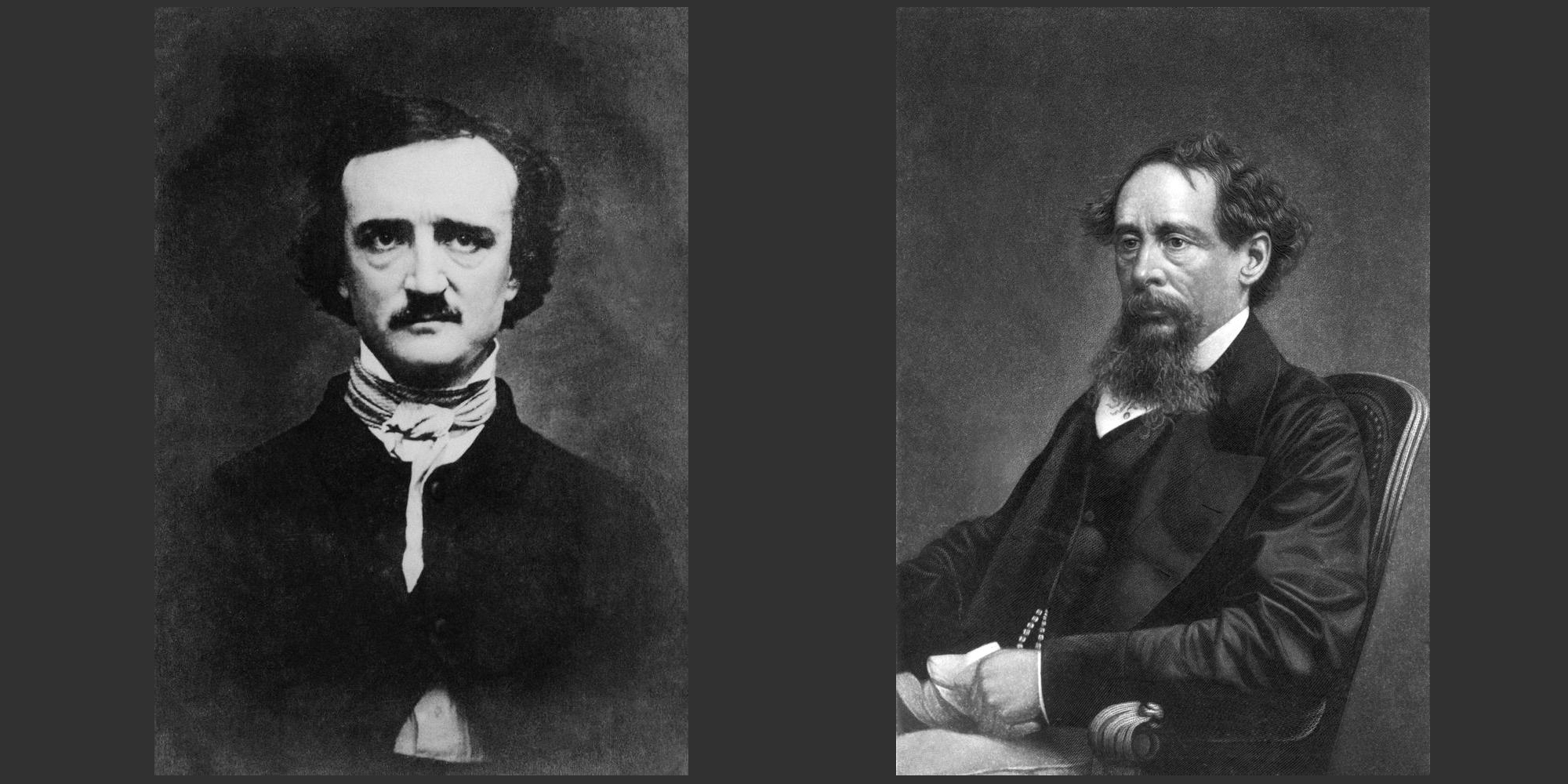

The men met twice in Dickens’ suite at the hotel, Poe in his neat but worn black suit, a portrait of gentile poverty, Dickens draped in fine clothes and jewellery for the first meeting, and in his dressing gown for the second. The meetings appear to have been scholarly and impersonal, although Dickens was travelling with a portrait of his children and Grip, and it is likely that he showed this to Poe given the latter’s enthusiasm for the ‘Grip’ of Barnaby Rudge. They discussed contemporary English and American authors, literary history, and composition, as well as the need for workable international copyright legislation. Poe is not mentioned in American Notes, and the author who made the greatest impression on Dickens during the visit was Washington Irving, who Dickens described as ‘my dear friend.’ But then, Irving was a literary giant, whereas Poe was, by Dickens’ standards, a nobody.

It was probably on the second visit that Poe made his move, asking if Dickens could help him find an English publisher for Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque. As a couple of surviving letters prove, Dickens promised that he would try. After returning to England, Dickens wrote to Poe in November:

Dear Sir, — by some strange accident (I presume it must have been through some mistake on the part of Mr. Putnam in the great quantity of business he had to arrange for me), I have never been able to find among my papers, since I came to England, the letter you wrote to me at New York. But I read it there, and think I am correct in believing that it charged me with no other mission than that which you had already entrusted to me by word of mouth. Believe me that it never, for a moment, escaped my recollection; and that I have done all in my power to bring it to a successful issue — I regret to say, in vain.

I should have forwarded you the accompanying letter from Mr. Moxon before now, but that I have delayed doing so in the hope that some other channel for the publication of our book on this side of the water would present itself to me. I am, however, unable to report any success. I have mentioned it to publishers with whom I have influence, but they have, one and all, declined the venture. And the only consolation I can give you is that I do not believe any collection of detached pieces by an unknown writer, even though he were an Englishman, would be at all likely to find a publisher in this metropolis just now.

Do not for a moment suppose that I have ever thought of you but with a pleasant recollection; and that I am not at all times prepared to forward your views in this country, if I can.

Four years later, Poe must have tried to work the contact one more time, again to no avail, because on March 19, 1846, Dickens wrote to him: When Poe met Dickens

Although I have not received your volume, I avail myself of a leisure moment to thank you for the gift of it.

In reference to your proposal as regards the Daily News, I beg to assure you that I am not in any way connected with the Editorship or current Management of that Paper. I have an interest in it, and write such papers for it as I attach my name to. This is the whole amount of my connection with the Journal.

Any such proposition as yours, therefore, must be addressed to the Editor. I do not know, for certain, how that gentleman might regard it; but I should say that he probably has as many correspondents in America and elsewhere, as the Paper can afford space to.

And that was that. Poe never received the patronage he desired, and he died in poverty and despair in 1849. When Dickens returned to the US in 1867, Poe’s posthumous reputation was growing. On visiting Baltimore, he learned that Poe’s mother-in-law, Maria Clemm, was still alive but in poor health and living in poverty. He made time to visit her and, on leaving, pressed a large amount of money into her hand. Back in England, he sent her a further $1000.

Statue of Edgar Allan Poe in Boston, MA

But the story does not end here. Barnaby Rudge and Grip had clearly lodged in the back of Poe’s mind. About three years after he met Dickens, Poe published his most famous poem, ‘The Raven’, in the New York Evening Mirror for a one-off fee of $9.00. The poem was an immediate popular and critical success, and remains one of the most iconic texts in gothic literature to this day. Though it is a matter of no more than informed conjecture, it seems likely that the model for Poe’s ‘Raven’ was dear old ‘Grip’. Poe’s contemporary, the ‘Fireside’ poet James Russell Lowell, saw the connection immediately, writing in his book-length satirical poem A Fable for Critics (1848):

There comes Poe with his raven, like Barnaby Rudge,

Three-fifths of him genius and two-fifths sheer fudge.

One cannot deny that ‘Nevermore’ is not so far away from ‘Never say die!’ and ‘Nobody’, and there are other notional textual similarities, for example this exchange of dialogue regarding Grip in Barnaby Rudge:

‘Ah! He’s a knowing blade!’ said Varden, shaking his head. ‘I should be sorry to talk secrets before him. Oh! He’s a deep customer. I’ve no doubt he can read, and write, and cast accounts if he chooses. What was that? Him tapping at the door?’

‘No,’ returned the widow. ‘It was in the street, I think. Hark! Yes. There again! ‘Tis someone knocking softly at the shutter. Who can it be!’

There are certainly echoes of this in Poe’s opening stanza:

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.” When Poe met Dickens

Equally, the lines from Poe’s seventh stanza, ‘In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore; / Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; / But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door’ reflect a similar description of Grip’s movement and demeanour from Barnaby Rudge: ‘After a short survey of the ground, and a few sidelong looks at the ceiling and at everybody present in turn, he fluttered to the floor, and went to Barnaby—not in a hop, or walk, or run, but in a pace like that of a very particular gentleman with exceedingly tight boots on, trying to walk fast over loose pebbles.’ You may pay your money and take your choice, but as previously noted, Poe could be what academics euphemistically refer to as ‘a little too close to his sources’ when necessity dictated. And though in the end he got very little help from Dickens in his own lifetime, he did at least receive the inspiration for his greatest poem.

We shall never know for sure, but the two – or is it three? – birds are now forever conceptually linked. After Dickens died in 1870, the America collector of Poe memorabilia Colonel Richard Gimbel purchased the original Grip. She can be seen today, still in her case, gazing balefully down, in the rare-book section of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Main image: Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens. Credits: World of Triss / Alamy Stock Photo and Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’. Illustration by Arthur Rackham (1867 – 1939). Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Barnaby Rudge and his raven Grip, part of a stone panel sculpted by Estcourt J Clack at the former home of Dickens on what is now Marylebone Road in London. Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: A 19th-century portrait of Dickens’ pet raven. Credit: Colin Waters / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Edgar Allan Poe statue in Boston MA. Credit: Randy Duchaine / Alamy Stock Photo

More information on the life and works of Edgar Allan Poe can be found here: Poe Studies Association

Our editions of Dickens’ and Poe’s works can be found here: Wordsworth Dickens and here: Wordsworth Poe

When Poe met Dickens

Books associated with this article

Barnaby Rudge

Charles Dickens