The Power of Expectation

Turning our eyes for the moment fully on the novel Great Expectations rather than its adaptation, Sally Minogue looks at the way Charles Dickens explores the power of expectation.

What a brilliant title! In two words Charles Dickens both raises our expectations and undermines them. For if we have great expectations, you can be pretty certain that they’ll be disappointed; irony is built into the phrase. This is the nub of Dickens’ novel. Expectations are raised for its hero Pip, first by his being taken up by Miss Havisham, and second via the financial support of his mysterious benefactor which hoists him into another class and future. And if his own expectations of himself are thus changed, he must also bear the burden of others’ expectations of him. The complicated itinerary our hero has to follow is determined by the interweaving of the two.

One might also see the power of expectation in the responses to the new television adaptation of the novel. I’m not going to dwell on that here, as I’ll be writing about it (alongside Stephen Carver) when the final episode has been aired. But the many disappointments and frustrations expressed in the reviews can be traced to the force of the reviewers’ preconceptions, piqued by the ‘Peaky Blinders’ provenance of the adapter, Steven Knight, on the one hand, and by the sacrosanct standing of Victorian novelist Charles Dickens on the other. The reviews were pretty much already written as soon as writer and cast list were announced.

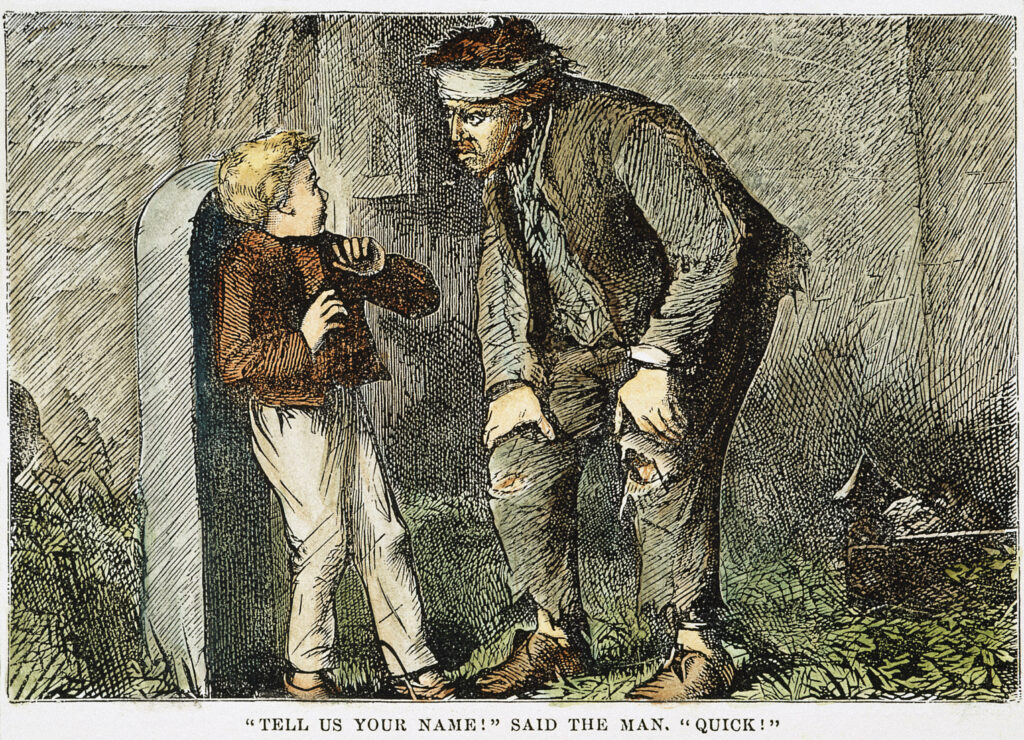

Pip’s first meeting with the convict, Abel Magwitch.

We see the powerful process and consequences of expectation writ large in Pip’s story. In the first chapters of the novel, when he is no more than a child, he has two dramatically formative experiences which change the rest of his life. The first is being intercepted by the escaped convict Magwitch as Pip contemplates the gravestones of his mother, father and five siblings; here he is ‘about seven’, according to Dickens’ carefully planned chronology. The second, a year or so later, is being forcibly taken up by Miss Havisham, to play a role in her bitter fantasies of revenge. In neither case does Pip have any agency. Magwitch seizes him and turns him upside down to empty his pockets for what he can find there. Miss Havisham summons him peremptorily to ‘play’ with Estella, and likewise turns his emotional and moral world upside down. The tragedy for Pip is that he misplaces the value of these two bouleversements: he understandably sees the Magwitch encounter as bad and – less understandably – the Havisham encounter as good. Similarly he thinks his mysterious benefactor must be Miss Havisham; it does not even occur to him that it could be the convict Magwitch (even though Miss Havisham has made it clear a number of times that once apprenticed to Joe there will be no rewards from her). The twists and turns of the narrative show us his sometimes self-deluding, sometimes desperate, sometimes noble attempts to understand the way in which his life has been influenced by his summary encounters with these two figures, and eventually to make amends for his own moral and emotional misunderstandings and mistakes.

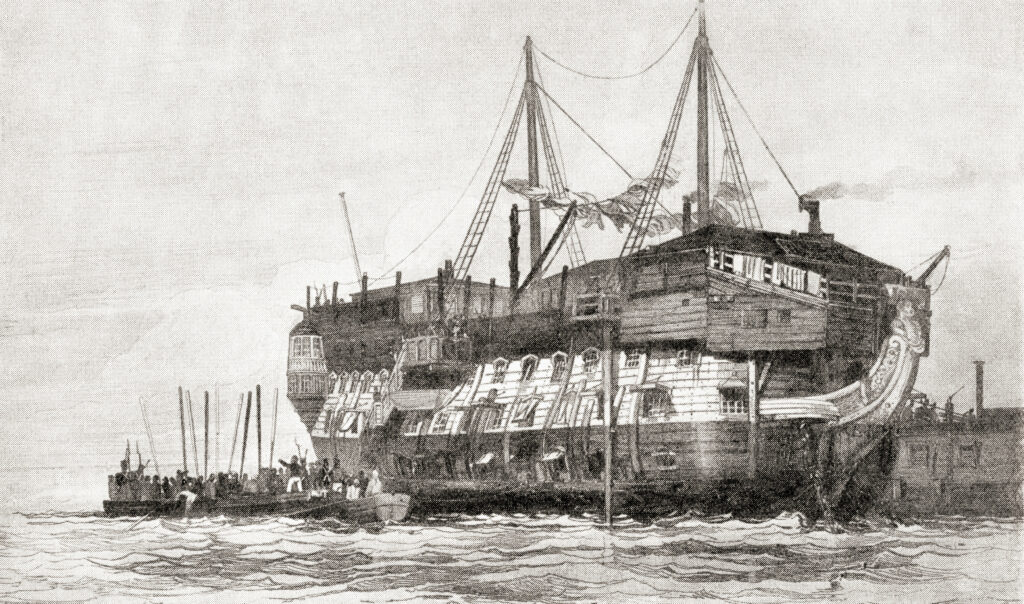

It is narratively daring to subject Pip to not one but two powerful interventions in his life, arriving when he is as yet unformed – a child on the way to becoming an adult. But it’s a stroke of genius then to link these to a moral dilemma which Pip himself cannot yet be aware of. He is hamstrung from the start. Add to that his early life, already full of the stuff of tragedy – an orphan, left in the care of a harsh sister twenty years his senior, whose physically abusive behaviour towards him (and to her hapless husband, Joe) would now bring in the social services. No such safety net in the Victorian world here laid before us, where convicts are kept in brutalised conditions on the prison Hulks on the Kent estuary, and a young girl and then a young boy can be annexed for the personal purposes of a wealthy woman. Of course, the latter is done with consent from Mrs Joe (Joe has little to do with it) and the cloak of respectability is provided by

Pip’s Graves, St James Church Yard, Cooling

Uncle Pumblechook. But what happens behind the iron railings and barred windows of the gloriously inaptly named Satis House is determined by the money and status of its mistress, and the whole point of her nasty experiment is that Pip, being lower-class and a child, has no say in what happens to him. Estella too is deeply damaged by the wanton exploitation of her from the age of three, but because when we meet her in the novel she has already been hardened and twisted by her ‘guardian’, and as a result treats Pip so badly, we feel less sympathy for her. But it is Estella herself who tells Pip when they are older and at quite a late stage in their relationship, as he is bidden to escort her towards a further step in her social education: ‘“We have no choice, you and I, but to obey our instructions. We are not free to follow our devices, you and I.”’

Pip however does not realise this in the same way as Estella, and perhaps this is the saving of him, since at key points on his journey he wrestles with the alternatives before him, genuinely believing he has a choice. And by the end of his story his good choices have prevailed to make him a better man. But on the way, it is the influence of those two initial encounters that provide the binding conditions which both prompt and limit his choices. As soon as Pip encounters the different world which Miss Havisham and Estella represent, his view of his own world is turned over. Estella’s immediate judgement of him as ‘common’ becomes his own:

“He calls knaves, Jacks, this boy!” said Estella with disdain, before our first game was out. “And what coarse hands he has. And what thick boots!”

I had never thought of being ashamed of my hands before; but I began to consider them a very indifferent pair. Her contempt was so strong, that it became infectious, and I caught it.

His reappraisal of himself sadly spreads to Joe too: ‘I wished Joe had been more genteelly brought up, and then I should have been so too’. As he had parted from Joe on this expedition – his first parting from him – he had wondered ‘why on earth I was going to play at Miss Havisham’s and what on earth I was expected to play at’. Now he knows.

This first brush with expectation sets Pip on a downward moral course, as the retrospective narrative voice of the mature Pip who is telling the story sees and shows, but of which the young Pip is as yet unaware. The first person narrative allows Dickens to reveal both the innocent Pip and his later self, rueing the way his younger self behaved. But the primary emphasis is on seeing things through Pip’s eyes at each stage of his development, so that at this point we retain our sympathy for that young innocence. Crucial to our sustained sympathy is the way that he struggles with his new feelings, and with a dim and perplexing awareness that there is something wrong in them. In this he has two important confidants, one being the very Joe whom he is mentally castigating for having taught him to call knaves, jacks; the other, the young Biddy, who is the good counterpart to all that is wrong in Estella. As Pip artlessly explains to each of them his state of mind and his changing view of his world, and why he wants to leave it, we see, as he does not, the hurt he is inevitably inflicting on them, the two shining figures in that world. Yet it is that very artlessness, and the fact that he at least has the sagacity to seek their advice and give them his confidence, which enables us to see the instinct for good in Pip. In this he has had the best model in Joe, and when he feels he must admit to Joe the lies he has invented about the visit to Satis House, the distress tumbles out of him:

And then I told Joe that I felt very miserable, and that I hadn’t been able to explain myself to Mrs Joe and Pumblechook who were so rude to me, and that there had been a beautiful young lady at Miss Havisham’s who was dreadfully proud, and that she had said I was common, and that I knew I was common, and that I wished I was not common, and that the lies had come out of it somehow, I didn’t know how.

The HMS York, a British prison hulk.

Joe’s beautiful disquisition on ‘common’, which would best most philosophers, ends with a piece of advice: ‘“Which this to you the true friend say. If you can’t get to be oncommon through going straight, you’ll never get to do it through going crooked. So don’t tell no more [lies], Pip, and live well and die happy.”’ But Pip is in the grip of Estella already, and, going upstairs to say his prayers, on Joe’s recommendation, ‘I thought long after I laid me down, how common Estella would consider Joe, a mere blacksmith: how thick his boots, and how coarse his hands’. His confession to Biddy of his desire to become a gentleman and the role of Estella in this is similarly framed to show the impossibility of escape for Pip from the grip of his new ambitions. Dickens, through the voice of the older Pip, does not spare our young hero; he is shown as self-centred, thoughtlessly unaware of Biddy’s own feelings, wrong-headed about his assumed superiority to her. But he does listen to her, as he listens to Joe; and even if he can’t escape the fine chain mesh that Estella has thrown around him, he again struggles to find within him his better self:

And now, because my mind was not confused enough before, I complicated its confusion fifty thousand-fold, by having states and seasons when I was clear that Biddy was immeasurably better than Estella, and that the plain honest working life to which I was born, had nothing in it to be ashamed of, but offered me sufficient means of self-respect and happiness.

This is a man arguing himself into a liking which we know, from Dr Johnson, is in the end not possible. But without these evident internal conflicts and conversations, and passages of reflection, we would not continue to care about what happens to Pip as we do.

It is at this moment of attempting to be satisfied where he is inwardly dissatisfied (shades of Satis House) that the second set of expectations is thrust upon Pip. In the fourth year of his apprenticeship, the lawyer Jaggers arrives to ask Joe if he would cancel his indentures ‘at his [Pip’s] request and for his good’, to which Joe of course assents. ‘“Now, I return to this young fellow. And the communication I have got to make, is that he has great expectations. … I am instructed to communicate to him … that he will come into a handsome property. Further, that it is the desire of the present possessor of that property, that he be immediately removed from his present sphere of life and from this place, and be brought up as a gentleman.”’

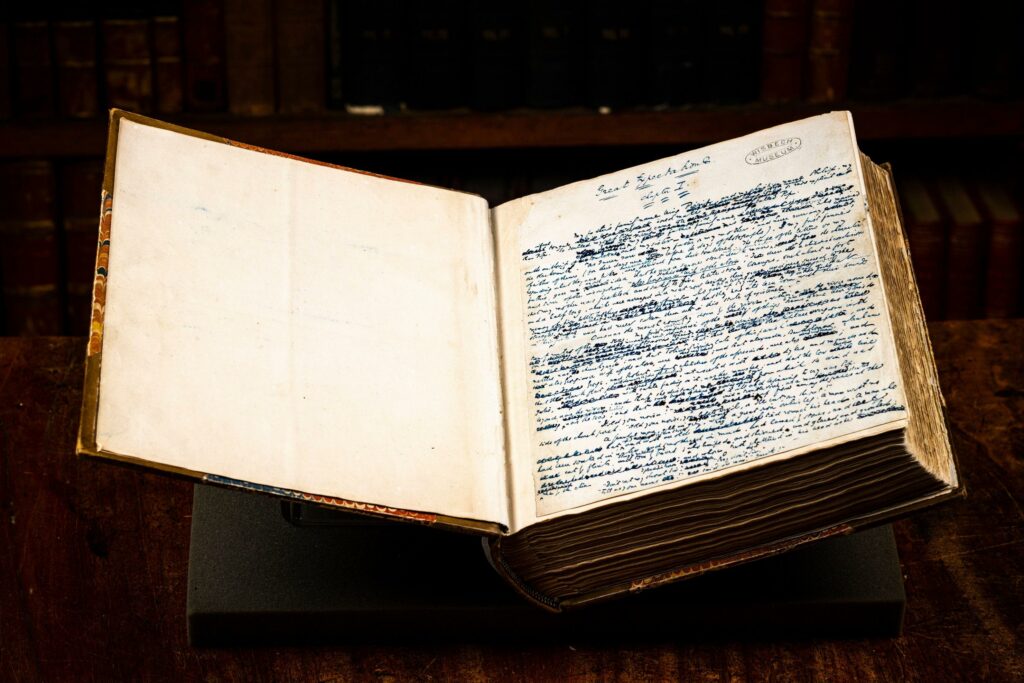

Opening page of the original manuscript of ‘Great Expectations’

Pip is by now, as we know from Dickens’s notes, aged 18, just on the cusp of adulthood. Suddenly his ostensibly hopeless desires are made flesh: ‘My dream was out; my wild fancy was surpassed by sober reality; Miss Havisham was going to make my fortune on a grand scale.’ Here begins the first of his delusions, and one which will wreak much havoc in his thoughts and feelings, since he sees it as a direction towards and in favour of Estella. In his mind being a gentleman has always been tied up with his desire for her, and now it seems to him that Miss Havisham’s expectations lie in that way too. As his adult self reflects at the end of Chapter 9, after his first summons to Satis House, ‘That was a memorable day to me, for it made great changes in me … Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day’. Thus Pip goes from one set of indentures to another, though now he is mistaken about who he is bound to.

Again Dickens explores and exploits the contradictoriness of expectation, and the twinned ironies of Magwitch’s benevolence and Miss Havisham’s malevolence. The ‘long chain of iron or gold’ which ties Pip’s heart forever to Estella was already set in place on that first day, but similarly when Pip stole the file to free Magwitch from his leg irons, a similar chain of feeling was forged between the two of them. When Pip brings him food, pities his desolation, and treats him civilly, and later when Joe forgives him for the pie with the words, ‘“We don’t know what you have done, but we wouldn’t have you starved to death for it, poor miserable fellow-creatur. – Would us, Pip?”’, the human chain of feeling stems from the compassionate impulse exactly opposite to that of Miss Havisham. Yet Magwitch’s grateful benevolence does Pip no immediate good; his expectations initially ruin him, in part because of his misplaced understanding of where those expectations have come from. Instead of now valuing all he is leaving behind, in Joe and Biddy and his broken sister and the forge, he cannot wait to depart, patronizingly assuring them (as though they might have thought otherwise!) that he will never forget them – which is precisely what he proceeds to do. Again the older narrator Pip paints a cruel picture of his own thoughtless self-centredness, though here too there are still touches of the sensitive Pip: as he sees Joe and Biddy beneath his bedroom window talking in soft tones about him, Joe smoking a late pipe for comfort, ‘I drew away from the window, and sat down in my one chair by the bedside, feeling it very sorrowful and strange that this first night of my bright fortunes should be the loneliest I had ever known’.

As before, however, Pip does not learn from these glimpses of his own proper feeling, and when – Pip not having gone back to Kent to visit – Biddy writes a note proposing a visit from Joe, he feels not pleasure, but mortification. He makes Joe feel ill-at-ease by his own unease. And, rather as with Estella, those in his acquaintance he knows to be good (the Pockets) do not concern him as to meeting Joe. But the thought of Bentley Drummle, whom he dislikes, even despises, meeting Joe makes him absurdly ashamed. On top of all this he begins to live too grandly, to get into debt, to lead his good friend Herbert Pocket into debt. He is still able to reflect on his situation and its ironies:

As I had grown accustomed to my expectations, I had insensibly begun to notice their effect upon myself and those around me. Their influence on my own character, I disguised from my recognition as much as possible, but I knew very well that it was not all good. I lived in a state of chronic uneasiness respecting my behaviour to Joe. My conscience was not by any means comfortable about Biddy. When I woke up in the night … I used to think, with a weariness on my spirits, that I should have been happier and better if I had never seen Miss Havisham’s face, and had risen to manhood content to be partners with Joe in the honest old forge.

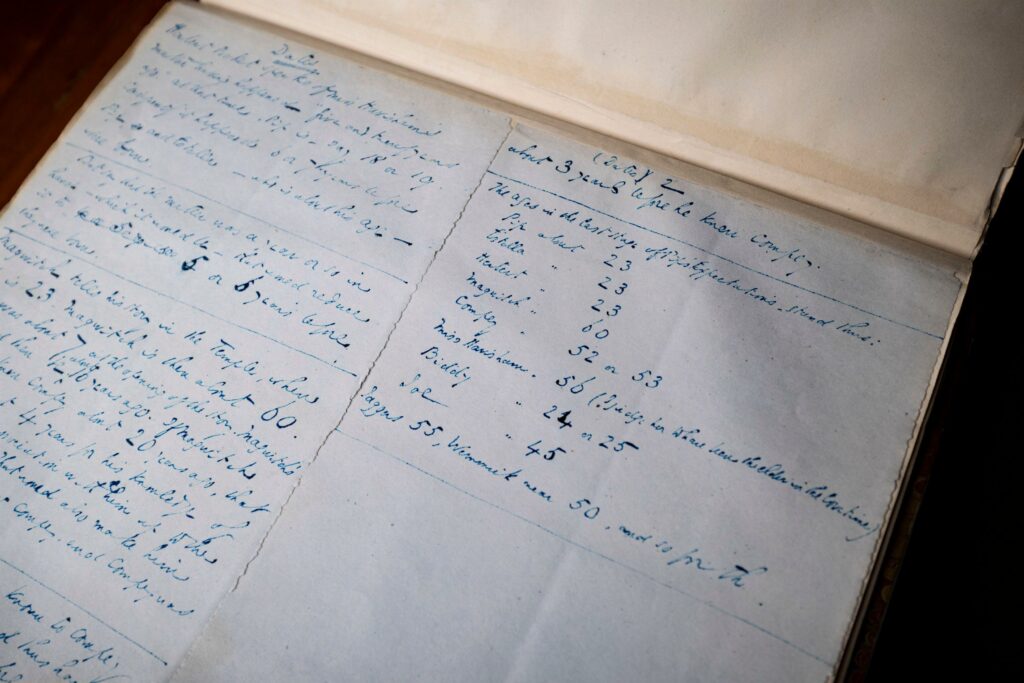

Pages of notes for the novel

But then he thinks of Estella, his need to be a gentleman for her sake, and sinks again under the weight of the old chains. His one good deed in this time is to use the £500 from his benefactor on his 21st birthday to benefit Herbert Pocket and see his future safe. But Herbert’s future would have been less in doubt if Pip had never blundered into it.

Halfway through the novel the twin expectations exerted by the Havisham side of the story and the Magwitch side come together, as Magwitch returns (under pain of death) to be reunited with Pip once more and to reveal the true nature of Pip’s great expectations. Once more Pip is turned upside down, but now he is able to see the truth of his life the right way up:

It was not until I began to think, that I began fully to know how wrecked I was, and how the ship in which I had sailed had gone to pieces.

Miss Havisham’s intentions towards me, all a mere dream; Estella not designed for me …But, sharpest and deepest pain of all – it was for the convict, guilty of I knew not what crimes, and liable to be taken out of those rooms where I sat thinking, and hanged at the Old Bailey door, that I had deserted Joe.

I would not have gone back to Joe now, I would not have gone back to Biddy now … No wisdom on earth could have given me the comfort that I should have derived from their simplicity and fidelity; but I could never, never, never, undo what I had done.

It is the business of the remaining part of the novel to undo what has been done, and for Pip to find in himself that better part which has been buried. Magwitch’s return brings to him a further sense of shame about Joe – yet even as he thinks how badly he has treated Joe because of Magwitch’s benefaction, he treats Magwitch in the same way and for the same reason – the thought of Estella. But as Pip hears Magwitch’s sad story, and realizes how much the old convict has sacrificed for him, and how deeply he cares for him, he is softened and comes truly to care for his benefactor. He can progress to this state of grace only by renouncing any further ‘expectations’, but manages things so that Magwitch when he dies, dies thinking that all he has will go to Pip. As Pip cares for the dying Magwitch, so Joe in turn cares for Pip on his sickbed, and Pip can become little Pip again, folded in the love of the one ungainsayably good man in this novel.

A cautionary tale then, but one in which Dickens cleverly and movingly shows a boy’s then a man’s struggle to find his true way forward under the weight of so many expectations. He shows us too the powerful effects of early dramatic and formative experiences, some of them – such as Pip’s love for Estella – inescapable, but some capable of change through reflection and the proper understanding of the place of an individual life in its relation to so many others. The masterly use of the double first person narrative gives us simultaneously the young Pip’s unadulterated experience and consciousness, and the older, experienced Pip’s mature judgements and understandings, and allows a space for compassion. We may take the more sombre original ending, when Pip and Estella briefly meet and then part forever, or Dickens’ revised, more hopeful, ending, where he sees ‘no shadow of a parting from her’. In either case, this is a novel whose final keynote is, perhaps surprisingly, forgiveness.

Main image: Stained glass roundel portrait of Dickens, from Dickens House, Doughty Street, London. Credit: Holmes Garden Photos / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Pip’s first meeting with the convict, Abel Magwitch. Wood engraving from a 19th-century American edition. Credit: The Granger Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Pip’s Graves, St James Church Yard, Cooling, Kent which is mentioned in the first chapter of the book. Credit: Homer Sykes / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: The HMS York, a British prison hulk. Prison hulks were decommissioned ships that authorities used as floating prisons in the 18th and 19th centuries. Credit: Hilary Morgan / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 & 5 above: The original manuscript and pages of notes for Great Expectations, usually kept in the vault of the Wisbech and Fenland Museum. Credit: Jason Bye / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

Great Expectations (Collector’s Edition)

Charles Dickens