Sally Minogue reflects on Hard Times

Hard Times: For These Times: Sally Minogue reflects on hard times in 19th century England as reflected in Charles Dickens’ novel, and hard times now.

The subtitle of Charles Dickens’ novel – For These Times – is usually dropped in modern editions, but it is significant for his writerly intentions. Dickens is announcing: I want to say something about now. And perhaps my own intentions in choosing to write about this particular novel are the same. We are living in hard times. The particular exigencies may be created by the pandemic, but it is the old hard times, those that are always with us, that link this 21st century back to the 19th. Harsh working and living conditions for the poor, created and sustained deliberately by the rich; a woeful level of protection from labour laws (worse in the 21st century, because the protection that had improved has again diminished); exploitation of women who live on a further level of powerlessness (yes, still); an education system nakedly designed as an instrument of capitalism; a brutal disregard for the works of the imagination. Dickens highlights all of the above in his portrait of Coketown, but I should issue a caveat: in old-fashioned ideological terms, his narrative viewpoint is bourgeois. His exposé of the relations of power is dimmed by his own prejudices – against unions, against women taking power into their own hands, against the rebellious working man. He shows the flaws, institutional and personal, in those who control capital and education, but in the end the working man and woman must be kept contained. Stephen Blackpool, one of the most original of Dickens’ creations, an intelligent working man who cannot accommodate the views of either the unions or the masters, and who even challenges the sexual mores of his time by trying to sue for divorce in order to marry his companionate Rachael, has of course to fall down an abandoned pit-shaft and die, just as he is on his way back to Coketown to clear his name.

Dickens highlights all of the above in his portrait of Coketown, but I should issue a caveat: in old-fashioned ideological terms, his narrative viewpoint is bourgeois. His exposé of the relations of power is dimmed by his own prejudices – against unions, against women taking power into their own hands, against the rebellious working man. He shows the flaws, institutional and personal, in those who control capital and education, but in the end the working man and woman must be kept contained. Stephen Blackpool, one of the most original of Dickens’ creations, an intelligent working man who cannot accommodate the views of either the unions or the masters, and who even challenges the sexual mores of his time by trying to sue for divorce in order to marry his companionate Rachael, has of course to fall down an abandoned pit-shaft and die, just as he is on his way back to Coketown to clear his name.

No getting out of that hole. Furthermore the wife he has tried to divorce must perforce be a drunken good-for-nothing, while his beloved Rachael must spend the rest of her life doing good works and thinking good thoughts, ‘sweet-tempered and serene, and even cheerful’. So while Stephen is placed before us as a sort of working-class hero, he cannot be allowed to triumph, and his philosophy of life is insultingly reduced to ‘’aw a muddle’, a befuddling of the clear-cut entrenched system set against him. There are no nuances for Stephen and his class.

But then there are no nuances for anyone in this novel. Hard Times is perhaps better taken as a satirical caricature than a realist novel, and if we see it like this we can accept its broad brushstrokes, most evident in Dickens’ choice of names for his characters. Blackpool’s name prefigures his own fate. Bounderby is a bounder, but his name also conjures his supreme lack of concern for those he bounds over (remind you of anyone?). Gradgrind is such an inspired name that it has become a lasting synonym for the attitude to education that the character encapsulates – though the name of his assistant, Mr. M’Choakumchild, is more comically graphic. Dickens was satirising a utilitarian philosophy of education specific to his time, but the reductive instrumentalism that Gradgrind’s values embody is certainly evident in today’s education system, damagingly so in our universities where the Humanities, once cherished as embodying the central values of a university, are in rout, in favour of supposedly ‘useful’ subjects (implying wrongly that there is no ‘use’ in Humanities). I’d been thinking to compare Gradgrind with Michael Gove, from his days as Education Secretary (2010-2014); yet that’s not quite right. Who, after all, could accuse the Right Honourable Secretary of State of sticking to ‘Facts … Facts alone … nothing but Facts’? I see however that his present title is itself worthy of a place in the high satire of the novel. He is now, amongst other things, Secretary of State for Levelling Up.

Dickens’ representation of the working man and woman may be limited, but he does at least give them representation in their own voices, and he was thorough in researching this. In a letter to his correspondent Mark Lemon, February 20th, 1854, he asked, ‘Will you note down and send me any slang terms among the tumblers and circus-people?’, so that he could give authenticity to the speech of Sleary and his circus companions. Likewise he worked hard on getting the voices of Stephen Blackpool and Rachael right, drawing on a contemporary reference book, A View of the Lancashire Dialect, by John Collier. [www.charlesdickenspage.com] In this he may have been piqued by the competition from Elizabeth Gaskell. Gaskell had already used a remarkably faithful representation of Manchester working-class speech to great effect in Mary Barton (1848, well ahead of Dickens). Dickens, as editor of Household Words, placed the serialisation of Gaskell’s North and South, another Manchester novel (September 1854-January 1855), to follow immediately from the serialisation of his own Hard Times, (April-August 1854). There was surely something of a power play here. Gaskell certainly felt compromised in her aim to represent a more complex picture of a Northern industrialised town, when that was to follow immediately on from Dickens’ monolithic view of Coketown. And initially the reception of her novel was less successful than that of Hard Times, while the weekly sales for Household Words during the serialisation of Hard Times rose by 237%. From our long vantage point, it’s now generally recognized that Gaskell’s is the more empathetic representation of working people – men and women – and their speech. But in his time Dickens was undeniably the more popular writer. [For more on Mary Barton, see Stephen Carver’s excellent blog, August 21st, 2021 here.]

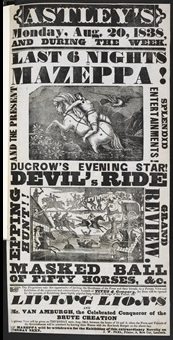

Let’s for now set aside Dickens’ patriarchal impulse to control fictional representation and reception through his editorship (what was I saying earlier about female powerlessness?) The power of his creative vision is undeniable, as is his highly inventive and playful use of language in its service, and both come down clearly on the right side in the debate between utility and imagination. Some of the most enjoyable passages in Hard Times are devoted either to showing the absurdity of a rationalism pushed to its most reductive end, or to conjuring the opposing charm of the world of imagination, brought to life in Sleary’s circus. Without that magical world, and the characters who belong to it, this would be a grim novel indeed. Dickens was fascinated by the circus world well before he wrote Hard Times. As a child he made several visits to Astley’s, one of the major Victorian circuses [www.bl.uk], and wrote about that experience in Sketches by Boz (1836). He also gave an account of Astley’s and its appeal in The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41):

Let’s for now set aside Dickens’ patriarchal impulse to control fictional representation and reception through his editorship (what was I saying earlier about female powerlessness?) The power of his creative vision is undeniable, as is his highly inventive and playful use of language in its service, and both come down clearly on the right side in the debate between utility and imagination. Some of the most enjoyable passages in Hard Times are devoted either to showing the absurdity of a rationalism pushed to its most reductive end, or to conjuring the opposing charm of the world of imagination, brought to life in Sleary’s circus. Without that magical world, and the characters who belong to it, this would be a grim novel indeed. Dickens was fascinated by the circus world well before he wrote Hard Times. As a child he made several visits to Astley’s, one of the major Victorian circuses [www.bl.uk], and wrote about that experience in Sketches by Boz (1836). He also gave an account of Astley’s and its appeal in The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-41):

What a glow was that, which burst upon them all, when that long, clear, brilliant row of lights came slowly up; and what the feverish excitement when the little bell rang and the music began in good earnest. … Then the play itself! The horses … the ladies and gentlemen … the firing … the forlorn lady … the tyrant … the pony who reared up on his hind-legs … the clown … the lady who jumped over the nine-and-twenty ribbons and came down safe upon the horse’s back – everything was delightful, splendid, and surprising!

This is an account from the beglamoured observer’s point of view. In Hard Times the circus world is fleshed out more fully. Certainly it is a symbol for all that is denied by Gradgrind’s system, but we see into the world itself, beyond the meaning attached to it. True, when we are first introduced to it, we can’t make much meaning of it. The circus patois employed by Childers and Kidderminster, as they try to explain to Bounderby and Gradgrind what has happened to Jupe, Sissy’s father, is a barrier to rather than a means of communication. The circus is a private world with its own backslang designed to repel invaders. But this is of course part of its very charm. And for those within it, it is a shambolic family whose embrace is always comforting, never judgemental. When Sissy realises that her father has abandoned her, she receives primeval comfort. She ‘broke into the most deplorable cry, and took refuge on the bosom of the most accomplished tight-rope lady (herself in the family way), who knelt down on the floor to nurse her, and to weep over her.’ Sissy is practically given mother’s milk (Dickens was surely aware of the double meaning of ‘nurse’), so abundant is the embrace she is held in, not just by the tight-rope lady, but by the whole circus. The ring and the big top represent a whole other world, and even an outsider who is lucky enough to be taken into the circle will be given nourishment (witness the rescue of Tom Gradgrind at the end of the novel).

So not only is Sleary’s circus an alternative to the harsh educational economics of Gradgrindism, it is an alternative to the bourgeois Victorian family itself. Bonds here are not made by blood but by community. When Bounderby avers that he is ‘willing to take charge of you, [Sissy] Jupe, and to educate you, and provide for you’, Sleary offers an alternative, an apprenticeship, but in circus arts and terms, a strange admixture of the world of capitalism with that of illusion:

If you like, Thethilia, to be prentitht [apprenticed], you know the nature of the work and you know your companionth. Emma Gordon, in whothe lap you’re a lying at prethent, would be a mother to you, and Joth’phine would be a thithter to you.

Sleary paints such an appealing picture that it’s hard to understand why Sissy doesn’t stick with her circus family. But Sissy wants more; she wants education, and most of all she wants to do what her father wished for her. The farewell offered to her by the circus family is affecting:

The basket packed in silence, they brought her bonnet to her, and smoothed her disordered hair, and put it on. Then they pressed about her, and bent over her in very natural attitudes, kissing and embracing her: and brought the children to take leave of her; and were a tender-hearted, simple, foolish set of women altogether.

This is a largely feminine scene, but Sleary too ministers to her in the end: ‘opening his arms wide he took her by both her hands, and would have sprung her up and down. … but there was no rebound in Sissy.’ There was no rebound in Sissy – a sad conclusion. She has to find her own way forward now, having made her choice. Yet she fares better than Louisa (Gradgrind), who makes a far harder choice, that of marrying Bounderby.

This Dickens novel is rare in that these two female characters are more fully conceived than his usual heroines, shown being faced with hard and complicated choices. Even if their agency is limited by their gender and their expected social role, we are at least shown them in the act of agency, making their decisions. Sissy and Louisa couldn’t be further from the infantilised Dora of Great Expectations, the continually miniaturised, eponymous Little Dorrit, or (another little) Little Nell of The Old Curiosity Shop. These women are never allowed by their author to truly grow up. By contrast, both Sissy and Louisa have to confront their own life choices, and in doing that each has to deal with a father, actual (in Louisa’s case) or missing (Sissy). Louisa’s is the striking case to a 21st century eye. We are introduced to her thus: ‘She was a child now, of fifteen or sixteen’; then we see Bounderby, thirty years her senior, entering what is effectively still the nursery and demanding a kiss:

“I’ll answer for its being all over with father. Well, Louisa, that’s worth a kiss, isn’t it?”

“You can take one, Mr Bounderby,” returned Louisa, when she had coldly paused, and slowly walked across the room, and ungraciously raised her cheek towards him, with her face turned away.

“Always my pet; ain’t you, Louisa?” said Mr Bounderby.

This chill scene is followed by Louisa rubbing her cheek ‘until it was burning red’, and exhorting brother Tom to ‘“cut the piece out with your penknife if you like”’. But that doesn’t stop Tom from turning Bounderby’s soft spot for Louisa to his own advantage (and what layers of meaning lie in that phrase ‘soft spot’). Eventually the formal institutions of a marriage proposal are pursued by Bounderby to Louisa’s father Gradgrind. Theoretically, Louisa still has a choice, one that is dramatised by Dickens in the encounter between her and her father. Louisa looks for a sign that her father understands her inner turmoil, and Dickens gives us a sense that that is almost imminent; but too great is the distance between them. There is a great deal about lack of communication in this novel. All that Louisa says is ‘”Yet when night comes, Fire bursts out, father’”. Fire does eventually burst out for Louisa, but not before she has been sacrificed on the twin desires of her brother (to curry favour with Bounderby in order to further his own career) and her father (whose motives are unclear, except that he is influenced by convention). They give her over to Bounderby, effectively. That ‘soft spot’ is in fact a hard spot.

Hidden in all of this is that Louisa is a sexual sacrifice. The writing conventions of the time mean that Dickens could not state this, but it is conveyed subtly. That first unwanted kiss – insignia of power, silently condoned by brother and father; the period before the wedding, when ‘Love was made … in the form of bracelets … and took on a manufacturing aspect’; to the wedding itself, when Tom congratulates his sister on being ‘a game girl’. All the men involved – including Dickens – know what is really involved in such a marriage. Does Louisa? There is something in her submission to that first Bounderby kiss that says she does. But the real sadness is that she knows that her father and brother know it also, and let it happen. When ‘the happy pair departed for the railroad’, we know, as does Dickens, that ‘happy’ is not the right word.

But Louisa finds her own way forward, and not the expected one of fleeing to the romantic attraction of James Harthouse – though who could blame her if she did? Instead, she reflects, and also causes her father, whom she consults, to reflect. Theirs is a mutual learning, dependent on a considerable act of charity on Louisa’s part given his initial hard-headedness. Whether or not we fully believe in Gradgrind’s extraordinary reformation, we do believe in Louisa’s slow burn of understanding. In the final chapter, Dickens unusually leaves it up to the reader as to how we think of Louisa’s fate. But one thing (he authorially avers) is certain for Louisa:

Happy Sissy’s children loving her; all children loving her; she, grown learned in childish lore; thinking no innocent and pretty fancy to be despised; trying hard to know her humbler fellow-creatures, and to beautify their lives of machinery and reality with those imaginative graces and delights … did Louisa see these things of herself? These things were to be.

There is always the threat of sentimentality in Dickens. But in this finale I think what he foresees for Louisa is not sentimental, because he has prepared the ground in the various stages she has had to go through to find this state of being. Along the way she is accompanied and sustained by Sissy. Theirs is a sisterhood worthy of the circus – not of blood, not of class, but of shared experience, knowledge, and finally love from one to the other. It carries through into the final pages, and is the closing story of the novel. In this it acts in counterpoint to the philosophy which is perhaps given its greatest imaginative life in Hard Times, even through Dickens’ disapproving satire of it. Bitzer – Gradgrind’s zealous convert to utilitarianism – puts it thus, when asked to overlook Tom’s breaking the law:

I am sure you know that the whole social system is a question of self-interest. What you must always appeal to, is a person’s self-interest. It’s your only hold. We are so constituted.

In Hard Times Dickens shows that we are not so constituted, or at least we need not be. Indeed a novel for these times.

Wordsworth publishes all the aforementioned Charles Dickens novels, as well as those of Elizabeth Gaskell.

Main Image: Hard Times by Oscar Gustav Rejlander (c.1860) Credit: Steeve-x-foto / Alamy Stock Photo

Additional images: Hard Times page proof (1854); Astley’s: Last 6 Nights of Mazeppa! (1838) Both held by the British Library

Books associated with this article