The Count of Monte Cristo: A classic adventure tale

“On the 24th of February, 1815, the look-out at Notre-Dame de la Garde signalled the three-master, the Pharaon from Smyrna, Trieste, and Naples.”

The Count of Monte Cristo begins and ends with voyages. The opening line heralds the arrival of the hero, the young sailor Edmond Dantès, in his native Marseilles after a voyage across the Mediterranean, while the final image of the novel is a sailing ship set against the horizon, captained by the same man. During the intervening 30 years and 1300 pages, in which Dantès is wrongly imprisoned, escapes disguised as a corpse, discovers a hidden treasure-trove of riches, reinvents himself as the wealthy and mysterious Count of Monte Cristo, and dedicates himself to a series of elaborate revenge plots, his character undergoes an extreme and cryptic transformation. To understand Dantès’ development, which is both brought about by and reflected in his travels across Europe, Asia and Africa, it is necessary to consider the historical setting of the book.

At the outset of the novel, which begins in 1815, Dantès is a simple sailor, unaware of the complex political webs spun across France throughout the previous decades. Sadly this ignorance leads him to fall foul of the system. Unlike the characters that come from better stock, such as Gérard de Villefort, the double-dealing prosecutor who imprisons him, Dantès had never learnt that loyalty in early-eighteenth century France must primarily be to oneself. In a time of such rapid changes, it had been shown that the humble could ascend to power and the mighty fall without warning, as demonstrated by the plight of the exiled Napoleon:

“The emperor, now king of the petty Island of Elba, after having held sovereign sway over one-half of the world, counting as his subjects a small population of five or six thousand souls,—after having been accustomed to hear the “Vive Napoléons” of a hundred and twenty millions of human beings, uttered in ten different languages,—was looked upon here as a ruined man, separated forever from any fresh connection with France or claim to her throne.”

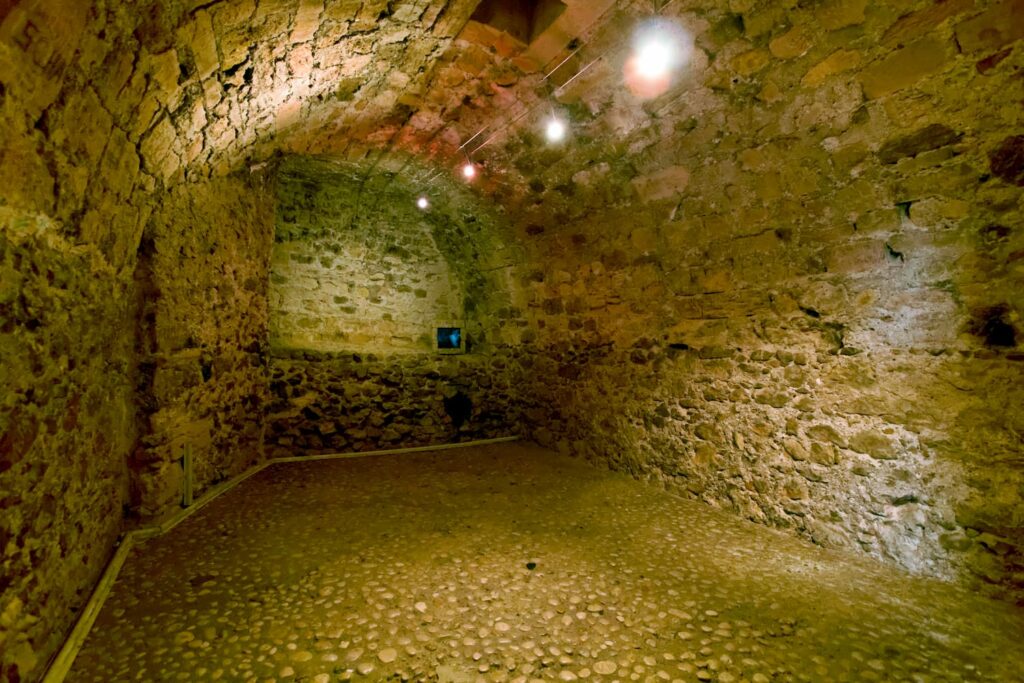

Prison cell in the Chateau d’If

In fact, Dantès was arrested on the false grounds of being a Bonapartist agent, “and as the most sanguine looked upon any attempt of Napoleon to remount the throne as impossible” his suffering was overlooked and ignored. And yet, just as he was being moved to his cell in the Château d’If fortress, Napoleon was launching another attempt to re-establish his power in France, moving against the Bourbon Monarchy during the so-called Hundred Days. Although his campaign failed, it provided a painful reminder for those who then considered themselves elites and authorities that their power was not as unassailable as they liked to believe. Ultimately, the events of the Hundred Days and the intricate designs of the Second Bourbon Restoration and later the July Monarchy have little bearing on the fate of Dantès, but do hold up a revealing mirror to his own life.

Just as the Revolutionary legacy Napoleon purported to uphold consisted in the abolition of France’s old and corrupt systems, Dantès’ series of revenges represents an attack on the country’s exploitative judicial, financial and political systems. These are embodied by his three main enemies: Villefort, who represents the law; Danglars, an important player in the banks; Fernand, an general in the army, a government official, and a recent-made nobleman. Beyond their betrayal of the protagonist, each man is shown to be an active agent in the twisted game they play.

Casually brushing off the appeals of a family whose son had been massacred in the French Army, Villefort states that “‘Every revolution has its catastrophes…Your brother has been the victim of this; it is a misfortune, and government owes nothing to his family’”. Danglars is likewise impervious to the suffering of others, caring only for the increase of his own estate, in the success of which he takes great pride and the failures of which he blames on others: “I increased our wealth, which continued to grow for more than fifteen years, until the moment when these unknown catastrophes, which I am still unable to comprehend, arrived to seize it and cast it down—without my being to blame, I might say, for any of it.” Fernand is the arch-traitor, showing no loyalty to anyone. He has Dantès sentenced to the Château d’If in order to marry his fiancée, fights against Spain despite being himself a Spaniard, and, as is later revealed, betrayed and killed the Ottoman ruler Ali Pasha, before selling his daughter and wife into slavery. As such, the ruin these three men face at Dantès’ hands is presented as deserved retribution for their corruption.

And yet far from epitomising the brave and honourable Frenchmen in this revolutionary act, Dantès is instead shown to have an affinity with foreign minority groups, those on the margins of society who notably lack Villefort’s power, Danglar’s riches and Fernard’s status. His origins as a sailor place him in the ranks of the Mediterranean seamen, whose various dialects, including Catalan, Neapolitan, Rumelian and Corsican, are all languages associated with separatist movements, attempts to challenge central powers and establish independence. Likewise, his native Marseilles is described as a centre of revolutionary spirit, its people desiring, “in spite of the authorities, to rekindle the flames of civil war, always smouldering in the south”.

At the start of the story, Dantès is preparing to marry Mercédès, a Spanish girl from the Catalan village situated quite apart from the French centre of Marseilles, again drawing him to liminal spaces. As the Count, he lauds the culture of the individual Italian states, celebrating both the pastoral society of the rural areas, where men work for themselves and benefit from their own efforts, and for their custom of vendettas, where “justice is only paid when silent”. Nowhere is more admired and more antithetical, however, than the mystical region known as ‘the East’.

“The Orientals, you understand, are the only people who know how to live”, states Dantès, promising that “when I have finished my business in Paris, I shall go and die in the East; and then if you want to find me, you will have to look in Cairo, Baghdad or Isfahan”.

‘The East’ or ‘The Orient’ in the novel has no clear geographical boundaries; sometimes it is India and China, sometimes Russia, but most often the Ottoman Empire, which at the time covered Turkey and the Caucasus, many areas and islands of Greece, the Levant and western Arabia, large swathes of the Middle East, and much of North Africa. A significant sub-plot revolves around the story of Ali Pasha of Ioannina, who during the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries ruled the Ottoman territory of Rumelia, that is, the empire’s European possessions. The Greek peoples and lands Ali commands are definitively included in the writer’s conception of ‘the East’. Even his portrayal of Marseilles is flavoured with exoticism, with its “burning…sun” and “Saharan winds”, the picturesque Oriental costumes, “suggestive of Greece or Arabia”, and the many dialects heard around its port.

Dumas had travelled to some so-called Eastern lands before and while writing The Count of Monte Cristo. In 1836 he attended feasts and visited great monuments in Tunisia, while in Algeria several years later he was hosted by his compatriot General Bugeaud, who had been consolidating the recent French control over the country with notoriously brutal tactics. Indeed, the conquest of Algeria takes place during the novel’s timeline, and Bugeaud himself is even referenced, although not by name.

At this time of imperial expansion, the East was often superficially perceived by Europeans as a mysterious land of occult knowledge and hidden riches, an impression naturally reinforced by the Napoleonic campaigns in Egypt. For this reason a distinction must be made between the East and Eastern peoples, the actual lands and inhabitants of Asia and North Africa with all their natural diversities and nuances, and the Orient and Orientals, those same people seen through the cosmopolitan, imperialist and Orientalist lens of the Europeans. It is a lens of which Dantès appears fully aware, and which he uses to his advantage. Before returning to France to seek vengeance, he adopts a persona much like that of an Oriental ruler, and is even bold enough to allude to this stratagem:

“Have you read the Thousand and One Nights? Can you tell if the people in it are rich or poor? If their grains of wheat are not rubies and diamonds? They look like penniless fishermen, don’t they? That’s how you treat them and suddenly they open up before you a mysterious cavern in which you find a treasure vast enough to purchase the Indies.”

In fact it is the fantasy of the Thousand and One Nights with which Dantès seems most enamoured, eagerly appropriating its tropes. As well as enriching himself with improbable treasures found in a hidden cavern, and assuming the pseudonym of Sinbad the Sailor among his many disguises, Dantès also infuses his revenge plots with smaller details borrowed from the Arabian Nights, from invisible ink to hidden compartments, hashish-induced escapades to slow and secret poisonings, noble bandits to enslaved princesses.

Dantès, as the Count, moves easily between opposites. He is a Frenchman but has adopted Oriental customs and aesthetics, he is now fabulously wealthy but knows what it is like to have nothing, and despite his acceptance into the highest ranks of Parisian society, continues to rely on bandits, smugglers and slaves to assist him. The cleverest part of the entire scheme is that through this mutability, he utilises the mechanisms of empire against those who symbolise it.

In the same way as the French were determined to subdue parts of the East, with one general writing in 1843 that “All populations who do not accept our conditions must be despoiled. Everything must be seized, devastated, without age or sex distinction: grass must not grow any more where the French army has set foot”, so Dantès too devotes every effort to the annihilation of his opponents, using a wide range of duplicitous, sometimes cruel, but ultimately very effective tactics. He is able to do so by creating a persona that combines the respectability and power of the French aristocrat with the mystery, allure and perhaps even savagery of the Oriental.

In travelling to Paris, where the majority of his adversaries now live, Dantès enters a city and a society that is supposed to be the antithesis of the East. As a great centre of European history, learning, art and religion, Paris is meant to epitomise western values and virtues. While they may joke about their vices, the aristocratic crowd certainly see themselves and their culture as superior to any found in the East. The mystery, exoticism and novelty of the East might hold a certain appeal in their eyes, but no serious comparison could be made between the importance, value and dignity of the two worlds. This too, however, is shown to be an illusion. Dantès tears at the façade of virtue held up by the Parisians, lifting the veil on their affairs, corruption and sins. Even as a Count, he refuses to fully enter their society, identifying as he does with the Orient; for this reason he is free to reveal and dismantle the rotten foundation on which it had been built.

Within the novel, the revenges of Edmond Dantès serve as a chilling reminder to the French authorities that their power can be challenged by those whom they have been used to commanding, oppressing and ignoring, a lesson that ought to have been learnt during the periods of violent upheaval recently seen in their country. Perhaps Dumas is also suggesting that ‘the East’, those places and peoples that Europe had invaded and exploited, might reappear one day as an avenger.

James O’Neill, playing the role more times than you can Count

Interestingly, Dantès affinity with the East in no way lessens his Christian faith. The Ottoman Empire was of course Islamic, although numerous other religions continued to be practiced within its borders, but despite his adoption of many Oriental customs, there is no implication that Dantès is ever tempted towards a conversion of any sort. In fact, the only French character to be described in relation to Islam is Bonaparte himself, with Villefort claiming “Napoleon is the Mahomet of the West, and is worshipped by his commonplace but ambitious followers, not only as a leader and lawgiver, but also as the personification of equality.”

Dantès’ uncompromising Christianity in the face of Eastern influences appears to reflect Dumas’ own perceptions. Writing about his visit to Tunisia, he comments that “The Arabs…saw no difference between the tomb of a French and a Muslim saint”. Although perhaps a somewhat naive view of religious tolerance, this suggests that the author saw the East as a space for the fusing, or at least the coexistence, of cultures, much like the character of Dantès.

Again when it comes to religion, although he makes continued references to God and his faith, the protagonist once more serves as a meeting point between two opposites. After slight moments of doubt during his imprisonment in the Chateau d’If, Dantès lives with a deep-seated conviction of God’s justice. Parallels between him and Jesus are evident: from humble beginnings he is betrayed, suffers terribly at the hands of the state authorities, but eventually returns with far greater power than they, as the Count of Monte Cristo, no less.

As he does with the secular aspects of Parisian society, Dantès also exposes the hypocrisy and demoralisation of religion within their ranks. Most of the aristocratic characters make reference to God only in passing, in oaths or curses, and the repeated claim that one is “a friend to the throne and religion” only highlights their caprice in a society where the throne had changed hands often, quickly, and violently. Criticism is also levelled at the contemporary church. The reader is reminded of the corrupt history of the Vatican through the story of the infamous Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI, to whom the treasure of Monte Cristo is said to have originally belonged. Furthermore, at Rome, an excited crowd gathers to witness brutal executions, bringing to light the hypocrisy of their judgements against the Orientals as barbaric, cruel peoples.

One of the most important questions, however, that Dumas implicitly poses to the reader in The Count of Monte Cristo also concerns Dantès’ religion. In the Chateau d’If, his fellow inmate Abbé Faria tells him that “God has supplied man with the intelligence that enables him to overcome the limitations of natural conditions”. His actions after escaping the fortress led the reader to wonder whether he might not have misinterpreted the Abbé’s words. In exacting his revenges, Dantès views himself as the executor of God’s judgement, one of “the men whom God has put above those office-holders, ministers, and kings, by giving them a mission to follow out, instead of a post to fill”.

Disguised as an abbé himself, he asks a man who has been stabbed as part of one of his schemes, “[do you] not believe in God when he is striking you dead? you will not believe in him, who requires but a prayer, a word, a tear, and he will forgive? God, who might have directed the assassin’s dagger so as to end your career in a moment, has given you this quarter of an hour for repentance.” Here Dantès indicates that his plots are the direct realisations of God’s will. Thus he seems to set himself on a dangerous path, justifying his manipulation and harm of others through his confidence in heavenly support. It is not difficult to see how this type of thinking could lead to the same sort of corruption that he initially appears to be challenging.

Dantès continues in his self-appointed role of divine agent throughout the series of revenges he enacts, and only at the very end of the novel does he realise that he had, “like Satan, thought himself for an instant equal to God,” and then “acknowledges with Christian humility that God alone possesses supreme power and infinite wisdom”. The abruptness and lack of explanation around this last-minute awakening seems anomalous in a work of such epic proportions. Moreover, the fact that it is revealed just as Dantès leaves France indefinitely for the East forces the reader to contemplate how sincere he truly is.

A man of many disguises, Edmond Dantès, the Count of Monte Cristo, deceives his opponents through the multifariousness of his identity. Both Frenchman and alien, he is impossible to pin down, not only for his fellow characters but also for the reader. Alexandre Dumas leaves us with the lingering question of how well we can know his protagonist, asking where the personas become the person.

Main image: Chateau d’If, Marseilles Credit: Anne Rippy / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Prison cell in the Chateau d’If. Credit: Giovanni Guarino Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: The actor James O’Neill who, from 1875, played the Count more than 6,000 times. Here he appears in the 1913 silent film version. Credit: Archive PL / Alamy Stock Photo

More information on the works of Alexandre Dumas can be found here: Alexandre Dumas Works

Our edition of The Count of Monte Cristo is here

Books associated with this article