Celebrating Pride

In Pride month, Sally Minogue reminds us of a time when writers couldn’t easily be out and proud.

A couple of weeks ago I was wandering through the cool paths of the Cimitero Acattolico – the Protestant Cemetery – in Rome, with fellow-blogger and friend Stefania Ciocia as my companion and guide. It was our very first point of pilgrimage, as we both wanted to pay our affectionate respects to John Keats, who is perhaps the most famous resident of this cemetery. If this place, and this starting point for my blog, seems a long way from the current celebrations of Pride in this country, stay with me on my wanderings, dear reader, and the path from one to the other will become clear.

Keats’s grave is much-visited, belying his bitter, self-chosen epitaph, ‘here lies one whose name is writ in water’. But so it seemed to Keats when he died, and he was sadly never to know what fame would come to him. That tugs at the heart, as it did for an earlier visitor, Oscar Wilde, who naturally wrote a poem upon the subject.

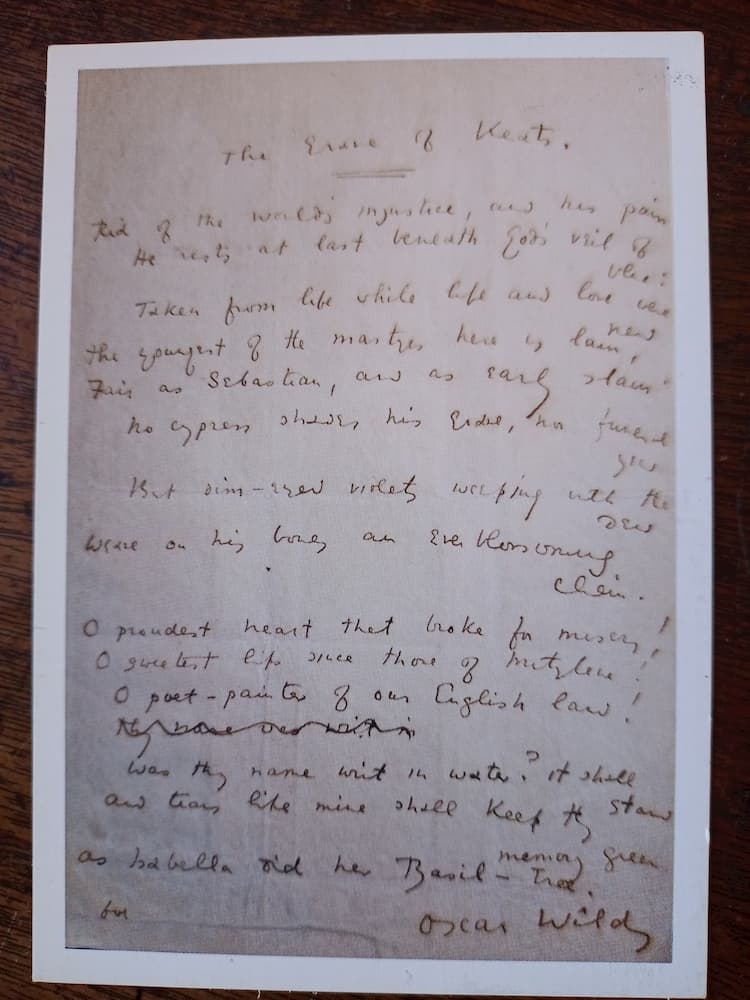

The Grave of Keats by Oscar Wilde

It’s not a terribly good poem, but Wilde can be forgiven for that – hard to get the tone right with such an obviously emotional subject, especially in the languorous poetic traditions of 1877 when he wrote the first draft, after his visit to the grave in late April (revised a while later to the final form illustrated here). Furthermore, Wilde was only 22, a Classics student at Oxford with his serious work as a writer still before him. The day was already a momentous one, since earlier Wilde had been vouchsafed an audience with the Pope, arranged by his travelling companion David Hunter Blair. This rather extraordinary event was clearly not enough to justify the day; in the evening he visited Keats’s grave, and by Blair’s account, threw himself on the ground before it – or possibly on it![1]

The histrionic gesture is not surprising from Wilde, who was already performative in his appearance and dress, but possibly too it was an expression of genuine feeling. It is indeed a most moving spot. In 1818, writing to his brother George, Keats had opined, ‘I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death’ (though he couldn’t have envisaged how soon that death would be). Only three years later, he feels that his poetic ambitions are all dashed, his name ‘writ in water’. The gulf between his sense of failure when he died and his subsequent supremacy ‘among the English Poets’ leaves us little consolation, other than the poetry itself.

Is Wilde’s cleaving to Keats, and his manner of expressing his sense of loss in his sonnet, part of his gay sensibility? Of course the grief he felt at that graveside, and the love of the poetry, might be shared by anyone; if there’d been no-one to see, I might have flung myself down in the same way. But certainly the romanticism of early or tortured death combined with the life of the artist has found a significant place in gay culture, particularly if it involves the beauty of the male body. No surprise that Wilde conjures the luckless, arrow-pierced, but very beautiful Sebastian as a counterpart to Keats – ‘Fair as Sebastian, and as early slain’ – and when he later writes about the visit he notes that ‘the vision of Guido’s St. Sebastian came before my eyes as I saw him at Genoa, a lovely brown boy, with crisp, clustering hair and red lips’.[2]

Saint Sebastian by Guido Reni

But he also invokes Mitylene, a little-known classical (female) figure: ‘O sweetest lips since those of Mitylene’. Many an adolescent reader has had a secret crush on Keats, roused by the sensuousness of his language (Christopher Ricks in Keats and Embarrassment is particularly good on this), but also by his beauty as shown in various portraits. So this is by no means peculiarly queer territory. But the dwelling on the kissable lips may be more so. Wilfred Owen, who echoed Keats’s ambition to be among the English poets, and shared his early death, wrote no poems overtly expressing male/male desire. But there is a constant trope of lips and kisses, sometimes combining the redness of the mouth with the blood of death. The critic Santanu Das is very insightful on the role of the male kiss in the history, culture and writing of the First World War, devoting a whole chapter to it in his superb Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature. Wilde didn’t like the plaque to Keats on the wall near his grave because he thought it represented his face as ‘ugly, and rather hatchet-shaped, with thick sensual lips’. I disagree – it seems to me a very affecting portrait in low relief, and on the day we visited jasmine hung freshly flowering around it, and the air was full of its scent.

Keats’ Grave

Wilde however preferred to see Keats as having either the lips of a classical female figure from mythology, or the ‘red lips’ of the martyred Sebastian. And ‘sweetest lips’ implies touch and taste – a desired kiss.

For all Wilde’s flamboyance and the way in which he seems sometimes to have flaunted his sexuality, he lived at a time when it was illegal to love as he did. He couldn’t at that point write openly about his desires, and the bravery with which he constantly pushed at the boundaries of social mores was promptly rewarded with humiliation, imprisonment, two years’ hard labour, and a subsequent early death. 46 years old, for goodness’ sake. Writing about an implied kiss seems almost absurdly innocent in the light of what was to happen to him, and from which stemmed some of his best writing, ‘De Profundis’ (1905) and ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’ (1898).

Wilde did by his own account share an actual kiss on another iconic poet of male/male desire, Walt Whitman. This was in New York in January 1882, only a few years after the visit to Rome; Whitman was already a grand literary figure, Wilde still in his late twenties giving a somewhat unsuccessful lecture tour. The conversation was not witnessed, but Wilde told a friend years later that ‘the kiss of Walt Whitman is still on my lips’.

It is a kiss that Virginia Woolf also dramatises in Mrs Dalloway (1925), that between Clarissa Dalloway and Sally Seton in their youth. Woolf writes very openly here about Clarissa’s love for Sally, through the device of her self-narrated retrospective consciousness (sometimes called free indirect narration):

The strange thing, on looking back, was the purity, the integrity, of her feeling for Sally. It was not like one’s feeling for a man. … it had a quality which could only exist between women.

…she could remember going cold with excitement, and doing her hair in a kind of ecstasy …

And while she emphasises the difference of the feeling from that she might feel for a man, she also compares herself with Othello (this is a book pulsing with Shakespearean reference), invoking his words, “‘if it were now to die ‘twere now to be most happy’”. This is unmistakably romantic and sexual love from a woman to another woman. So that when we get to the kiss, it is invested with great dramatic power, though described very simply as a natural act:

She and Sally fell a little behind. Then came the most exquisite moment of her whole life passing a stone urn with flowers on it. Sally stopped; picked a flower; kissed her on the lips. The whole world might have turned upside down! The others disappeared; there she was alone with Sally. And she felt that she had been given a present, wrapped up, and told just to keep it, not to look at it – a diamond, something infinitely precious, wrapped up …

It remains wrapped up, however. It may be ‘the most exquisite moment of her whole life’ but she ends up married to Richard Dalloway, an exquisitely boring, self-important man, for whom the most important thing in the novel is that the Prime Minister arrives at his party. And when Sally also arrives she turns out to have ‘married, quite unexpectedly, a bald man with a large buttonhole who owned, it was said, cotton mills at Manchester. And she had five boys!’ The five boys are oft-repeated, both by a triumphant Sally and a disappointed Clarissa; Woolf has a cruel eye.

If there is a social commentary here it would be surprising. Woolf rather lays before us what once was and what now is. The kiss and the desire and the most exquisite moment are all real; but so too are the worthy husbands, the boys at Eton, and the comfort, affluence and reassurance of being of a certain class. There’s no doubt that the moment of the kiss is the zenith of Clarissa’s experience, but it doesn’t eclipse the rest except in memory.

Was Woolf freer to write about same-sex love and desire between women because that was never criminalised? Possibly so, though Radclyffe Hall had her novel The Well of Loneliness (1928 – only three years after Mrs Dalloway) banned, in spite of its actually being less explicit than the passage quoted from Woolf. Her novel dwelt on overtly lesbian themes and depicted a woman somewhat like herself, occupying a male identity. It also included the plea, ‘Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our own existence!’ Jonathan Cape took the novel on, but it came under immediate attack from the Sunday Express and was eventually judged obscene because it defended ‘unnatural practices between women’. It was eventually republished in England in 1949. Radclyffe Hall’s mistake was to make her novel a plea for a particular sort of sexuality. Woolf by contrast includes that theme alongside and threaded through many others; she normalises it.

It’s a mark of a rich text when it is taken up and reinterpreted imaginatively by a later writer. Michael Cunningham’s The Hours (1998) did that with Mrs Dalloway in a most interesting way, weaving in contemporary gay subtexts and placing both Woolf’s private world and her fictional one alongside the Aids epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s. Usually I hate meta-fictions. But this was one that really worked, and was then transmuted into a film which reached a wide audience. Woolf lived again in another guise.

And now we are in 2023. Pride is a month, not a day. Pride has no adjective, it is instantly recognisable. And then again, having no adjective skirts the problem of which adjective to use. Of late, the politics of sexuality have become polarised and problematic. I even wonder whether I should be writing about these matters as a (notionally anyway) straight person. But my whole life has been spent in the love and service of literature. It remains my central belief that the power of literature is its ability to step into other lives – any other lives. A writer imagines. A reader enters that imagined world. It’s what writing does. Some writers will imagine better than others, and some of those writers will do so because of their experience of what they are writing about. Others will have had no experience of what they imagine. And if we think that the power of the writer depends on or is determined by their experience, that must also apply to the reader. Once a stop is put on the powers of invention of the writer, and the powers of reception of the reader, we might as well kiss imaginative literature goodbye.

The Gramsci tomb

I started with the Cimetero Acattolica, and I used the Italian deliberately, because it conveys better than the English translation the way the cemetery is defined against Catholic orthodoxy. The place is somewhere and somehow other. It is at the edge of Rome, only just within the Aurelian walls. Its atmosphere of peace and quiet, its shady paths and monuments, the sense of order and harmony are in direct contrast to the noisy, lively, hot historic centre of the city. While it has been associated with the burial of non-Catholics, and so with the English visitors who died in Rome, it is also home to non-believers and has, through the very variety of those represented and the monuments that represent them, an air of the secular. For example, Gramsci, a vitally important Italian thinker, Marxist philosopher, and victim of Mussolini is buried there. He died in prison in 1937, also at the age of 46.

The Protestant Cemetery is at the edge of Rome (like Keats’s grave, on what is now the very edge of the cemetery, though once it was near the only entrance). That on-the-edge-ness still characterises much of queer writing, as perhaps it also characterises the experience of what is still defined (for example by Pride itself) as sexually other. At the same time, Pride month has become almost corporate, and I wonder whether that is true to the spirit of Pride. I went to collect a train ticket at my local station; the machine was bedecked with rainbow bunting. I went into Waitrose to get some shopping; their customer service counter had a Happy Pride banner.

Waitrose Pride

When I politely asked if I could take a photograph of it, the young man behind the counter said “Of course!”, as though it was daft to ask. Of course, along with the corporate commodification comes a social acceptance, an obvious contrast to the incarcerated Wilde. That is without question progress. The television programme I Kissed a Boy (there’s that kiss again) puts gay relationships into the same category as Love Island heterosexual ones, with a touch more of sweetness and innocence (though I found it ultimately rather a sad programme).

But let’s not end on a sad note. One of the abiding images of Pride locally for me is the video footage of our newly-appointed Lord Mayor in Canterbury, Jean Butcher, a long-time councillor, dancing with abandon in the procession. Whatever happens the rest of the time, and in spite of terrible legal strictures in some other countries, here in the month of June we celebrate Pride together, and honour those writers who were at the forefront of what was not yet even a movement, and when lives were on the line. We salute you.

My blog for last year’s Pride gives chapter and verse for writers published by Wordsworth who explore these areas. A further blog on Walt Whitman examines closely the extent to which his poetry expresses male/male desire.

Christopher Ricks, Keats and Embarrassment, Oxford, 1974

Santanu Das, Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature, Cambridge, 2005

[1] I’m indebted to James Kidd and his blog for the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association website, 5 February, 2021, ‘“The Grave of Keats” by Oscar Wilde’, keats-shelley.org, which gives a lengthy and interesting account of these events.

[2] Oscar Wilde, ‘The Tomb of John Keats’, the Irish Monthly, July 1877

Main Image: Pride Festival, London. Credit: Mark Thomas / Alamy Stock Photo

Images 1,3,& 5 above courtesy of Sally Minogue

Image 2: Saint Sebastian, 1615 by Guido Reni. Credit: GL Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4: Catholic cemetery, Rome. Credit: Andrea Sabbadini / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

The Well of Loneliness

Radclyffe Hall

Orlando

Virginia Woolf