David Stuart Davies looks at The Diary of a Nobody

David Stuart Davies takes a look at the classic Victorian comedy novel, ‘The Diary of a Nobody’.

‘The funniest book in the world’

Evelyn Waugh

‘True humour … with its mixture of absurdity, irony and affection … a masterpiece, immortal’

J.B. Priestley

Written in the late nineteenth century, The Diary of a Nobody is comic and satirical scrutiny of the minutiae of suburban life and middle-class ambitions; it created a loose outline for later writers to take up the format, providing the inspiration for such works as the diaries of Bridget Jones and Adrian Mole to name just two.

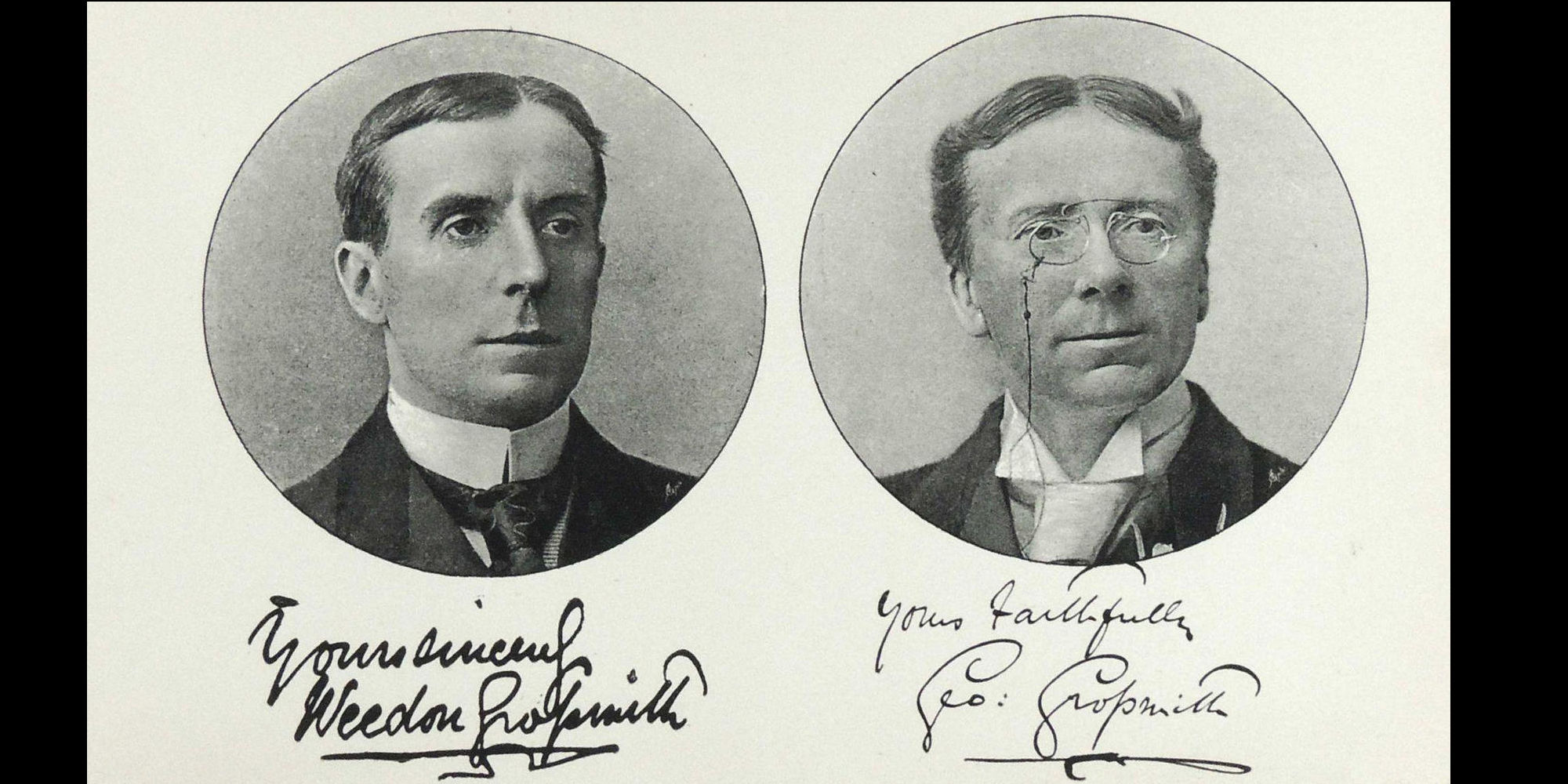

The book was written by George Grossmith and his brother Weedon who also illustrated it. The Diary of a Nobody first appeared in Punch magazine as short occasional whimsical pieces from May 1888 to May 1889. It started as a parody, mocking the proliferation of diaries and memoirs prevalent at the time. Punch had already published spoof diaries of a pessimist, a dyspeptic, a duffer and an MP. Everybody who was Anybody was publishing diaries, so why shouldn’t a Nobody? It did not appear in book form until 1892 when the text was extended and new illustrations were added.

The Diary records the daily events in the lives of a hapless London clerk, Charles Pooter, his wife Carrie, his son Lupin, and numerous friends and acquaintances over a period of fifteen months. The humour is based on lower or lower-middle class aspirations and pretensions. Pooter’s diary chronicles his daily routine, which includes small parties, minor embarrassments, and home improvements. Mr Pooter is a man of modest ambitions, content with his ordinary life and yet he always seems to be troubled by disagreeable tradesmen, impertinent young office clerks and wayward friends, not to mention his devil-may-care son Lupin with his unsuitable choice of a bride.

Pooter is a farcical individual, a figure of fun, staid, always attempting to maintain an overly respectable persona while being occasionally priggish or pompous and constantly straining to preserve his dignity but never quite succeeding:

‘I left the room with silent dignity, but caught my foot in the mat.’

With this bumbling, absurd, yet ultimately endearing character of Pooter, the Grossmith brothers created a wonderful portrait of the class system and the inherent snobbishness of middle-class suburbia – one which sends up the late Victorian crazes for Aestheticism, spiritualism and bicycling, as well as the fashion for publishing diaries.

The clever aspect of the presentation of Pooter is that the authors never ridicule him; it is for the reader to see the humour in the character’s failings. And indeed in all his social gaffes, he remains unaware of his own small-minded comic persona:

‘Left the shirts to be repaired at Trillip’s. I said to him: ‘I’m ‘fraid they are frayed.’ He said, without a smile, ‘They’re bound to do that, sir.’ Some people seem to be quite destitute of a sense of humour.’’

Despite the strong Victorian background and mores, the novel has a persuasive timeless quality. It seems to confirm that whatever the period setting, man’s foolishness is relevant for all seasons. Allan Massier in a recent article in the Daily Telegraph observed:

The Diary of a Nobody offers a double pleasure. It takes you back in time to an age which is presented with mocking and accurate affection, and the characters ring true for our time too. Some of us may have been taught by a Pooter and we have certainly heard a Pooter deliver the Thought for the Day on Radio 4’s Today programme.’

Despite the high regard in which the novel is held today, initial public reception was muted, and popular success was not evident until the third edition appeared in October 1910. After the First World War, the book’s popularity continued to grow, prompting regular re-printings and new editions, ensuring that thereafter it was never out of print.

In the years after the Second World War, the book’s stock continued to remain high. Respected cartoonist Osbert Lancaster deemed it ‘a great work of art’, and similar enthusiasm was expressed by a new generation of writers and social historians such as Gillian Tindall, who stated in 1970 that she thought the Diary was ‘the best comic novel in the language’, and lauded Pooter as ‘the presiding shade’ of his era.

For the authors, the novel was only a small part of their lives and careers. George Grossmith (1847-1912) initially worked as a journalist, reporting police court proceedings for The Times. In 1870 he began a highly successful career as a singer and entertainer, creating some of the most memorable characters in Gilbert and Sullivan’s operettas. His brother Weedon Grossmith (1854-1919) was educated at the Slade and the Royal Academy with a view to following a career as a painter and exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery and the Royal Academy. Joining a theatre company in 1885, he toured the provinces and America.

The Diary of a Nobody has been the subject of several stage and screen adaptations, including Ken Russell’s ‘silent film’ treatment of 1964, a four-part TV movie scripted by Andrew Davies in 2007, and a widely praised stage version in 2011, in which an all-male cast of three played all the parts.

In 1963, Keith Waterhouse published Mrs Pooter’s Diary an adaptation of the original that shifts the narrative voice to Carrie Pooter. This was later turned into a stage play in 1986 with real-life married couple Judi Dench and Michael Williams in the lead roles.

The novel remains as fresh and appealing as it did when first published. Charles Pooter has become one of the greatest comic icons in literature and as the notes on the back cover of the Wordsworth edition observe: ‘If you can read this without laughing aloud you have no sense of humour’. Or as Pooter himself would phrase it: ‘quite destitute of a sense of humour.’

Books associated with this article