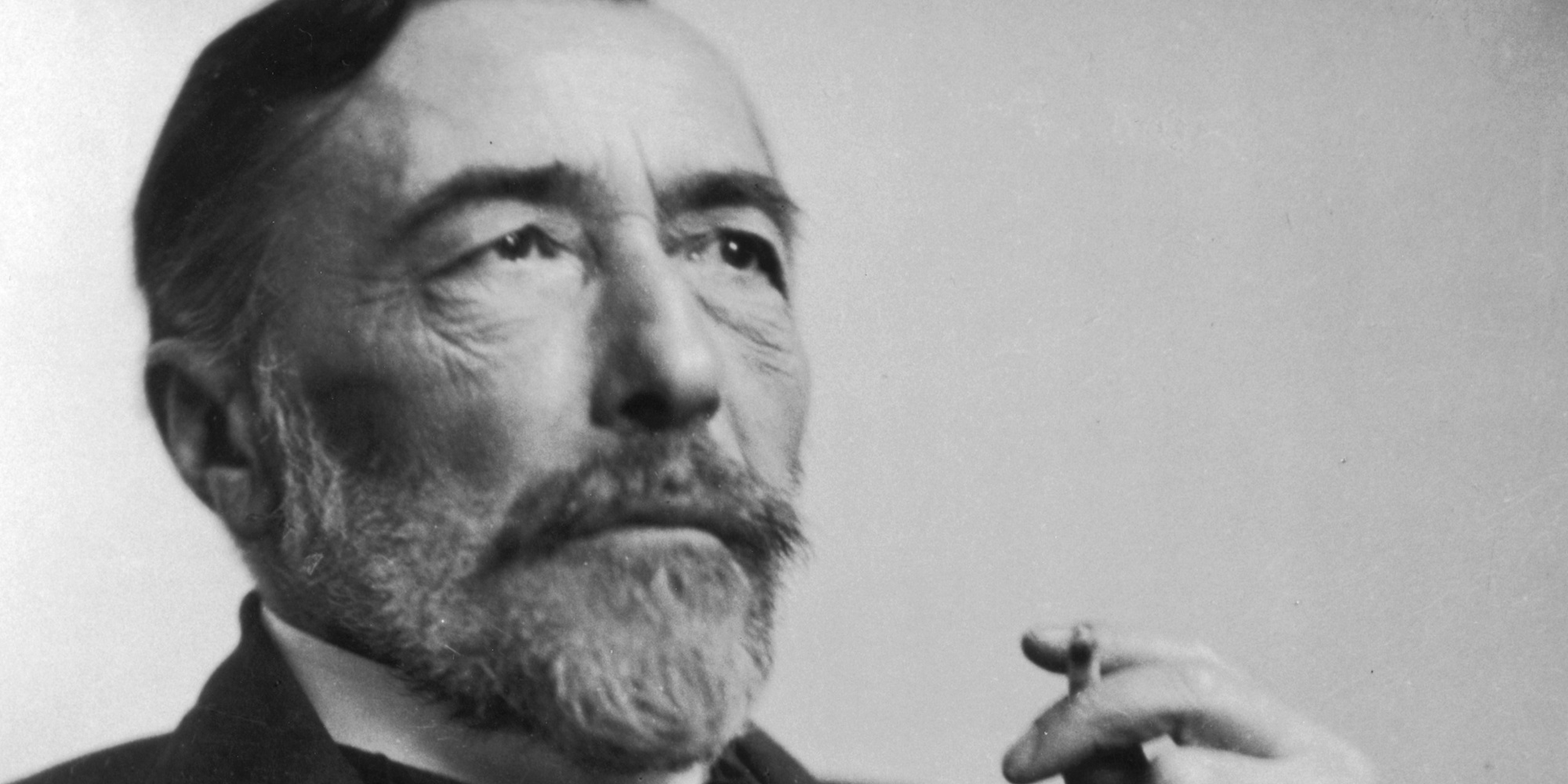

‘Why I wept on first reading Conrad’ – Part One

Keith Carabine looks back to the origins of his life-long love of Joseph Conrad

These personal reflections are an adaptation of my closing address to the 40th Anniversary Conference of the Joseph Conrad Society (U. K.), founded at a conference at Kent University in 1974. This talk was my last after 20 years of being Chair of the Society and after much dithering, at the very last minute, I decided, as the saying goes, to ‘get deep down and personal’ and talk about how I first stumbled upon Conrad as an undergraduate at Leeds in the spring of 1961 and what he meant to me then. ‘Stumbled’ is exactly right because when I first arrived at Leeds in the autumn of 1959 I was a theology student. More than halfway through my first term I was leaving a seminar on Hinduism and shared my enthusiasm for polytheistic religions with an earnest older chap who hoped to become a Methodist minister and he replied: ‘It’s all right Keith, but it’s not t’t true faith, is it?’ I found myself saying, ‘Ray, you’ve done me a huge favour’. ‘’av I upset you?’ ‘No Ray, but you’ve crystallised something for me. I’m getting out.’ I went straight over to the English Department Office and asked to speak to the Chair, Prof. Norman Jeffares who had told his secretary that he did not want to be disturbed. I pleaded with her to allow me to knock on his door and understandably Jeffares was deeply irritated to meet an importunate young man pleading with him ‘to help me to change my life’. Fortunately, he was a genial Irishman who laughed heartily when I told him about Ray and he said I could start an English degree the following year. ‘No’ I replied, ‘I have to start it now’; and when he protested that I had missed too many classes, especially in Old English which was compulsory, I assured him that I could catch up with the latter over Christmas and that I had already done much of the reading for the Introductory course on Modern Literature because I was lodging with students studying English. ‘What books have you read’ he asked, and I replied ‘I’ve read a lot of YEETS’. ‘Have you really?’ he asked, and then we talked about our shared fondness for YEETS for some 20 minutes and he allowed me to join the English Department forthwith. Later that day, I told my fellow lodgers that I was now an English student and learned that the correct pronunciation of Yeats was ‘YATES’ and that A. N Jeffares was the world’s foremost authority on him and that the volume of Yeats I had been reading was in fact edited by him! (Incidentally, I instantly recognised that Jeffares had manifested an extraordinary grace in not correcting an ignorant youngster).

Because the intellectual climate in the Leeds English Dept was a mixture of Leavis and Marxism you will not be surprised to learn that I began with Conrad’s great political novels The Secret Agent and Nostromo, together with Lord Jim. As a 20-year-old my admiration for Conrad was sparked by the drollery and black comedy arising out of the multiple cross-purposes of the characters and by Conrad’s astonishing switches of voice, point of view and chronology. I was dimly aware that Conrad demanded an active reader who was willing to construct the chronology of events in Nostromo for himself and to negotiate the puzzling, opposing viewpoints on, and interpretations of, a given event such as Jim’s jump or of a totemistic commodity such as the silver in Nostromo from which there is no escape in this world. And I remember struggling feebly with the notion that the sub-title of The Secret Agent was ‘A Simple Tale’. But, and this is my subject, I am sure that my love of Conrad was sealed by the tears I shed on first reading The Secret Agent, Lord Jim, and Nostromo.

I concentrate on the three passages that prompted my tears. Let us turn to the first, taken from the closing pages of the penultimate chapter (X11) of The Secret Agent when Winnie Verloc rushes out of the shop after stabbing her husband and terrified of the gallows and bent on suicide falls into the astonished arms of the philanderer, Ossipon, who is loitering and hoping to ‘fasten himself’ upon Winnie ‘for all she’s worth’ because he mistakenly thinks that it was Verloc who had been blown to pieces by the bomb and not Stevie, Winnie’s simple-minded brother. Like most first-time readers I was amused and appalled by the black comedy generated by the characters’ misreading of each other and by the narrator’s mischievous description of Ossipon’s amazement at his swift success with Winnie and his consternation when she tells him that she has spoken to the police; and then his sheer funk and panic after he stumbles upon ‘Mr Verloc in the fullness of his domestic ease reposing on a sofa’ with a knife stuck in his chest! From this moment on, Winnie for Ossipon, the disciple of Lombroso the criminologist-anthropologist who even to a twenty-year-old was a patent fool, is like her brother, Stevie, “a degenerate” but “of a murdering type.” Hence he fears for his life and cannot wait to abandon her on the train. Ossipon’s strangled Lambrosian reflections lead into the sequence that prompted my tears:

“He was an extraordinary lad, that brother of yours. Most interesting to study. A perfect type in a way. Perfect!”

He spoke scientifically in his secret fear. And Mrs Verloc, hearing these words of commendation vouchsafed to her beloved dead, swayed forward with a flicker of light in her in her sombre eyes, like a ray of sunshine heralding a tempest of rain.

“He was that indeed,” she whispered, softly, with quivering lips. “You took a lot of notice of him, Tom. I loved you for it.”

“It’s almost incredible the resemblance there was between you two,” pursued Ossipon, giving a voice to his abiding dread, and trying to conceal his nervous sickening impatience for the train to start. “Yes, he resembled you.”

These words were not especially touching or sympathetic. But the fact of that resemblance insisted upon was enough in itself to act upon her emotions powerfully. With a little faint cry, and throwing her arms out, Mrs Verloc burst into tears at last.

Ossipon entered the carriage, hastily closed the door and looked out to see the station clock. Eight minutes more. For the first three of these Mrs. Verloc wept violently … She tried to talk to her saviour, to the man who was the messenger of life.

“Oh, Tom! How could I fear to die after he was taken away from me so cruelly! How could I! How could I be such a coward!”

She lamented aloud her love of life, that life without grace or charm, and almost without decency, but of an exalted faithfulness of purpose, even unto murder. And, as so often happens in the lament of poor humanity rich in suffering but indigent in words, the truth-the very cry of truth-was found in a worn and artificial shape picked up somewhere among the phrases of sham sentiment.

“How could I be so afraid of death! Tom, I tried. But I am afraid. I tried to do away with myself. And I couldn’t. Am I hard? I suppose the cup of horrors was not full enough for such as me.”

The whole sequence is desperately sad as we watch Winnie clutch at straws, inventing a past relationship with the appalling Ossipon whom she now regards as her ‘Saviour’. I began to cry over the narrator’s compassionate testimony to Mrs Verloc’s ‘exalted faithfulness of purpose, even unto murder.’ Mark was my favourite gospel so I picked up on the echoes of Christ in the garden of Gethsemane lamenting ‘My soul is exceedingly sorrowful even unto death’ and then her ‘very cry of truth’ (‘I suppose the cup of horrors’) recalled Christ plea to his Father to ‘Take this cup away from me.’ Conrad’s linking of the humble Winnie with Christ’s agony in the garden is humane and moving, but the floodgates opened when I read ‘As so often happens in the lament of poor humanity rich in suffering and indigent in words.’ My tears manifested an uncomplicated response because I felt at that moment and still feel today that Conrad’s beautiful formulation spoke for my mother and grandmother and women like them who were indeed like Winnie ‘rich in suffering’ when, following the Second World War they struggled for decency and against poverty, sometimes alone because their husbands had been killed, and sometimes with hapless, damaged men, in damp, small, terraced houses in a smog-laden, dirty slum in central Manchester. Women like my mother and maternal grandmother gritted their teeth and demonstrated a ‘faithfulness of purpose’ as they devoted their lives to their children’s welfare and future, as Winnie and her mother had for poor Stevie. When I was eight my mother married a sweet, intelligent, damaged Irish navvy who after a few drinks topped by brandy was transformed into a nasty and abusive drunkard; and, of course, we were all in his firing line and I was aware that my mother’s love for me was something he couldn’t handle. My mother’s ‘indigence in words’ accompanied her fearful sense ‘that things are not worth looking into’ and that personal feelings must be repressed: otherwise all hope of maintaining family decencies would be shattered—as, of course, they often were. Winnie’s unconditional love for Stevie took place behind her husband’s back and proved, cruelly, to be of no avail and she sups the cup of horror to the full; without the unconditional, protective, self-sacrificing love of my mother and grandmother, I would not be standing here today.

In 1961 I did not realise that I was responding to Conrad’s commitment in his ‘Preface’ to The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ to presenting ‘the obscure lives of a few individuals out of all the disregarded multitude of the bewildered, the simple, and the voiceless.’ Nor did I realise then that I would become preoccupied, especially in my teaching, by the great task that Wordsworth (as far as I’m aware) initiated, of how to give voice to the voiceless, and of the difficulties of representing them using ‘the real language of men.’

In 1961 I had, in fact, not read much English Literature and Conrad’s astonishing ironic method of working for both pity and scorn was new to me and my tears took me by surprise. And, of course, I never thought of them as a fit subject for an undergraduate essay. I was then, however, owing to my theological interests, a devotee of Dostoevsky and I had devoured Crime and Punishment, The Devils, and The Brothers Karamazov. And if I remember rightly I wrote a superficial, look-at-me-I’ve-read-Dostoevsky essay on The Secret Agent and Nostromo on the ways Conrad’s ‘caricatural presentation’ (‘Author’s Note’) of Vladimir the cynical Russian diplomat and the motley anarchists and of such vain, foolish figures as General Montero and Sotillo reminded me of Dostoevsky’s scornful, often savagely funny portrayals of such muddled social theorists as Lebezniatkov in Crime and Punishment and Shigalov in The Devils. I cannot resist citing the latter who offers to his fellow dreamers ‘my own system of world organisation so as to make any further thinking unnecessary’ only to discover that ‘my conclusion is in direct contradiction to the original idea with which I start. Starting from unlimited freedom, I arrived at unlimited despotism. I will add, however, that there can be no other solution to the social formula than mine’. (I discovered years later that Conrad’s pithy version of the same appalling [prophetic?] possibility [truth?] appears in an early letter of 1885: ‘Socialism must inevitably end in Caesarism’ (Collected Letters, 1, p.16).