David Stuart Davies looks at Rob Roy

David Stuart Davies looks at the most popular of Sir Walter Scott’s novels, Rob Roy.

Walter Scott (1771 – 1832) was the most widely read novelist of the early nineteenth century. A Scot by birth, most of his fiction was based on the history of his native land. He became famous for ‘The Waverley Novels’. Scott did not publicly acknowledge authorship of these books until 1827, and so the series took its name from Waverley, his first novel published in 1814. The later books bore the words ‘by the author of Waverley’ on their title pages.

Scott’s adventure yarn, Rob Roy, (1817) was perhaps his most successful novel in this series. It not only captured the imagination of the growing reading public but also garnered praise from other writers. Robert Louis Stevenson considered it the best of Scott’s novels and said that he would never forget ‘the pleasure and surprise’ he felt on first reading it as a child. He also stated ‘When I think of Rob Roy I am impatient with all other novels’ Famed literary critic William Hazlitt was similarly impressed and wrote of the book: ‘Sir Walter has found out (oh, rare discovery!) … that there is no romance like the romance of real life.’

It is interesting to note that the titular character only makes an appearance halfway through the book. However, his charismatic personality and heroic actions are key to the novel’s development. Rob Roy emerges as a larger-than-life Robin Hood-type figure who was based on a real character from Scottish history, Robert Roy MacGregor, a renowned outlaw, who later became a folk hero.

Scott took incidents from MacGregor’s life and wove them into a rousing adventure story with the backdrop of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715, which aimed to restore the Stuart monarchy in the person of James Edward, the ‘Old Pretender’, son of the deposed king, James II.

The novel is notable for being told partly in Scots dialect, and for its depiction of the living conditions endured by many Scots in the early 18th century. Scott’s meticulous research into the period brings it to rich detailed life and while being an exciting work of fiction, the novel is also a testament to the social conditions of the times in which it was set.

Events are related in the first person by a young Englishman, Francis (‘Frank’) Osbaldistone. At the start of the novel, Osbaldistone refuses to join the family business and so his father, disappointed by his son’s intransigence, dispatches him to Northumbria, with word to his Uncle, Sir Hildebrand, that the first cousin, Rashleigh, should be considered the replacement for Francis in the proffered business career. There, at the Uncle’s estate, Francis meets for the first time both his cousins, including Rashleigh, and the enigmatic Diane Vernon, a beautiful, mysterious, and profoundly capable young woman with whom he falls in love. Along the way, he encounters the strong, silent Mr Campbell, who turns out to be Rob Roy. With this, we see one of Sir Walter Scott’s preferred devices, that of introducing his hero in disguise. This he did in his later novel Ivanhoe (1820).

Rashleigh steals financial documents essential to the Osbaldistone family and escapes to Scotland. Frank decides to gain help from Rob Roy in order to restore his father’s honour. Rob Roy is a leader of a band of Highlanders and is presented as an honest and upright highland gentleman, who has been forced into a life of blackmailing and banditry, at which he excels, being strong, bold, crafty, and fearless. Notorious throughout the Western Highlands, he is either loved or hated by other clans.

One of the most exciting set pieces in the novel is the depiction of the Battle of Glen Shiel in 1719, in which a British army of Scots and English defeat a Jacobite and Spanish expedition that aimed to restore the Stuart monarchy. The battle, in which Rob Roy is wounded, is described with a remarkable dramatic and vivid flourish.

In some ways, the story is the quintessential English-Scottish encounter and does not give up its secrets until the very last page. Few novels can match it for suspense and narrative daring, and in the swirl and colour of its characters.

The book was written between the spring to late summer of 1817 and published anonymously in three volumes on Hogmanay of that year. The demand for the novel was huge and it was said that a cargo vessel sailed from Leith to London containing nothing but copies destined for the capital’s bookshops. The original print run of 10,000, a huge figure for the time and indeed today, was sold out in two weeks. It has never been out of print.

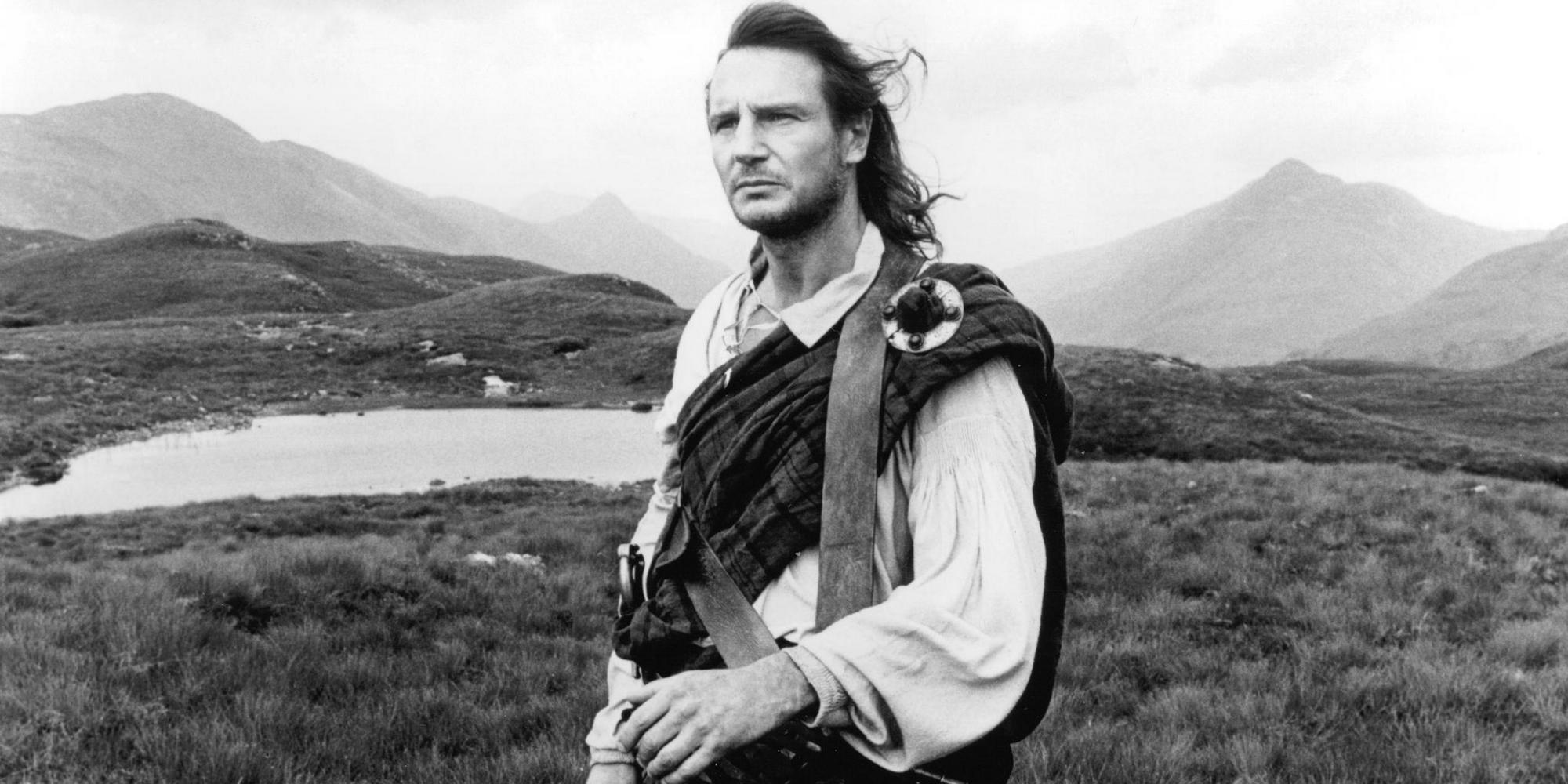

There have been two major film versions of the novel both of which, wisely or not, have played fast and loose with Scot’s intricate narrative and have presented a simple action movie featuring a likeable rogue called Rob Roy with little adherence to the plot of the novel. The first version, Rob Roy, The Highland Rogue, came in 1953 from the Walt Disney studios featuring Richard Todd (who had already played Robin Hood for the same company) as the hero. One review observed that it was ‘stiffly acted’ and might have been better as ‘a cartoon.’ Hollywood had another go in 1995 with Liam Neesom in the title role. Again, this took Scott’s character and the Jacobite rebellion and created its own narrative mainly unrelated to the plot in the book. Empire magazine stated that the movie was ‘profoundly mediocre.’

In truth, the convolutions of the plot and the fact that despite his dramatic flair, Rob Roy is a subsidiary character in Scott’s version, make a faithful film adaptation untenable. For a full and detailed flavour of the tale, one must pick up the novel. However, it has to be said that some of the Scottish dialects are challenging and require patience and a little guesswork. Nevertheless, the scenes of action and the depiction of time and place make the effort very worthwhile.

Pictured: Liam Neeson in the ‘profoundly mediocre’ 1995 film adaptation

Books associated with this article