Listening for the leaden circles dissolving in the air

Stefania Ciocia finds new harmonies in The Hours and Mrs Dalloway

“In a play, if more than one person speaks at the same time, it’s just noise. No one can understand a word. But with music, with music you can have twenty individuals all talking at once, and it’s not noise – it’s a perfect harmony. Isn’t that marvellous?” says Mozart to Joseph II in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus (1979). Five years after its premiere at the National Theatre, Amadeus shape-shifted into a critically acclaimed film, under the direction of Miloš Forman and with a screenplay written by Shaffer himself. I was eleven when the cinematic adaptation – now arguably more famous than the play – was released, and I must have been twelve when I watched it, on television. It made a huge impression on me: the thought that one could be a genius and earthy was nothing short of thrilling. The soundtrack wasn’t bad either.

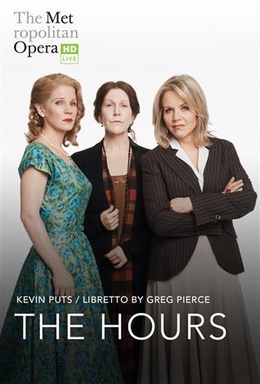

Poster for the opera ‘The Hours’

Mozart’s pronouncement that “only opera can do this”, weaving together multiple narrative strands in a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, has come back to mind on many wonderful musical occasions over the years. Its truth hit me again, paradoxically at my local cinema, during a live relay from the Met last December. I was watching The Hours, composed by Kevin Puts to a libretto by Greg Pierce, and based on Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1998 novel of the same name. The unique dramatic potential of opera has never felt more congenial to transposing a work of fiction into a different artistic medium than in this commission. Exploiting the gift for simultaneity of musical theatre, Puts can bring to the fore with unprecedented intensity the resonances between the three parallel stories first charted by Cunningham, and subsequently by Stephen Daldry, whose 2002 film adaptation of the novel is also credited as inspiration for this new work.

In every (re)telling, this rich, layered tale charts one day in the lives of three women, separated in time and place, and yet linked by material and thematic connections. At the heart of the piece is Virginia Woolf, in her home in Richmond, in 1923, absorbed in the early stages of writing The Hours, which will be published two years later as Mrs Dalloway, a novel spanning the course of one day. Then there is Laura Brown, pregnant with her second child in 1949 Los Angeles, a housewife stifled by domesticity and seeking refuge in the pages of that very same book. And finally, Clarissa Vaughan, Cunningham’s late 20th-century reimagining of Clarissa Dalloway: a successful literary editor, living in the West Village with her partner Sally, she is about to throw a party for her friend and former lover Richard, a poet who is dying of AIDS.

Like Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, Clarissa embraces the role of the consummate hostess, with all the superficial interactions that it entails, but is also a deeply introspective character, conscious of her frivolities and contradictions, and vaguely embarrassed at the prospect of being perceived as a socialite. The two women’s days encompass mundane tasks and thoughts, and far-reaching events and reflections; the membrane between the quotidian and the extraordinary always porous, especially when powerful memories collide with, and colour, the here and now or, conversely, when the present moment in time summons the past.

Their parties too bridge different spheres, as private acts of caring for the significant men in their lives, for whom the public limelight is ostensibly reserved: Mrs Dalloway’s hostessing oils the wheels of her husband’s political connections – the Prime Minister himself may pay a visit – while Clarissa’s celebration marks a prestigious literary accolade awarded to Richard, the prize that ought to cement his reputation as a writer of note for posterity. Death lurks at the edges of Clarissa’s preparations for the party then, instead of turning up as a wholly unexpected guest as it does when Dr Bradshaw, on arriving at the Dalloways, announces that one of his patients has taken his life by jumping out of the window earlier that evening.

The spectre of mortality is present in the other two storylines in The Hours. It is there in Woolf’s grappling with the composition of her novel, when her thoughts move from that elusive first sentence to reconsidering key events in the narrative; the initial idea that her main character should die gives way to the revelation that it will be Septimus Warren Smith, the shell-shocked veteran whose day unfolds in tandem with Mrs Dalloway’s, to kill himself, as will be casually recounted by his physician at the party, when the two plots intersect at last.[1]

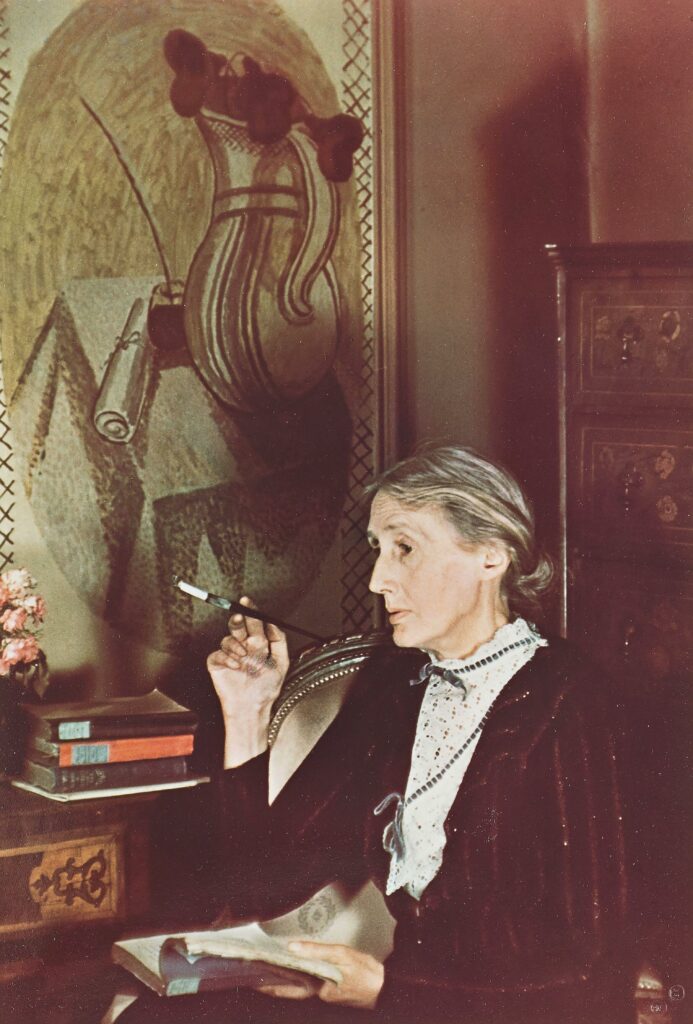

Virginia Woolf 1939

We also see Woolf battling with her demons, afraid of a relapse in her mental health condition and yet bristling against her husband Leonard’s solicitous ministrations, and the suburban quiet of Richmond, an exile from the intellectual and social stimuli of London’s bustling artistic scene. The only heralds from that world, invited for tea at four, are her sister and her three children. Their contingent is both bohemian and somewhat conventional. Vanessa, an artist in her own right, turns up a full hour and a half before expected, dispensing with formal niceties without second thoughts. To Virginia, however, she appears as the epitome of domestic competence: here are two middle-aged married women, the younger sister observes, but she will never have children, and is ill at ease in dealing with servants, whereas Vanessa is fully in command as a mother and as a housekeeper.

While Virginia is engaged in a perceived power struggle with her maid Nelly, Vanessa effortlessly disabuses her offspring of the notion that they will be able to save the thrush they have found, ill, in the road. In a matter-of-fact manner, the children are instructed to make the bird comfortable and let her die in the garden, where they arrange a flowery funeral bed. “It could be a kind of hat. It could be the missing link between millinery and death”, thinks “bird-sized” Virginia. The episode is one of many prefigurations of ideas that will find their way into Mrs Dalloway where Clarissa and Septimus are frequently associated with avian imagery, and Septimus’s wife Rezia is a milliner.

Unlike Septimus, Laura Brown’s husband Dan has returned from the war unscathed; in fact, he has come back from the dead, having believed to have been one of the casualties at Anzio, to make a devoted and contented family man.[2] In Laura, however, these loving bonds increasingly induce the sense of being oppressed, particularly by her little boy Richie, whose boundless need for her is overwhelming. The role of hostess is incumbent on her too, as on Clarissa and Virginia. It is Dan’s birthday, and the task of baking a cake for him, instead of being a joyful activity and an opportunity for complicity between mother and son, engulfs Laura with disappointment in her circumstances, and with the guilt she experiences for feeling this way.

On an impulse, Laura leaves Richie with a babysitter, and checks into a hotel for the freedom to carry on reading Mrs Dalloway undisturbed; in this room of her own she contemplates a different, irreversible escape. This is the second transgression of the day for Laura; the first had been kissing her neighbour Kitty, when she had dropped by to share some troubling news. Kitty, who has been struggling to conceive, has been diagnosed with a uterine growth in need of further medical investigation and – Laura reflects while pondering her own demise – may be dying of it.

Laura and Kitty’s kiss is an echo of young Mrs Dalloway and Sally Seaton’s, at Bourton, recalled by the former as the most exquisite moment in her life. In The Hours, Clarissa Vaughan feels much the same about a kiss with Richard, the summer when she was eighteen and they had been lovers. In the present day, she finds a sudden, unexpected pleasure when she kisses, on the cheek, Barbara, the woman she has been buying flowers from for years. In 1923 Richmond, “Virginia leans forward and kisses Vanessa on the mouth. It is an innocent kiss, innocent enough, but just now, in the kitchen, behind Nelly’s back, it feels like the most delicious and forbidden of pleasures”.

Bust of Virginia Woolf, Tavistock Square

What is shown by this rhapsody of kisses – passionate, casual, chaste, provocative, the sign of acknowledged and unacknowledged desires – is the fleeting nature of grace, but also the ordinariness in which it manifests itself, often in unplanned gestures and unremarkable situations that somehow find us, or even make us, ready to perceive it and bask in it. The preciousness of these breakthroughs is intensified by reminders that time is passing: Woolf punctuates Mrs Dalloway with the chiming of Big Ben, the “leaden circles dissolv[ing] in the air”, a motif referenced by Cunningham in the first chapter in Mrs Brown’s subplot, and incorporated musically by Puts in his score.

Against the ticking of the hours, Laura decides not to end her life, but returns home with a new self-awareness that will lead her to take a delayed, drastic decision in future; half a century later, Richard drops to his death from his apartment window in Clarissa’s presence, telling her: “I don’t think two people could have been happier than we’ve been”. These parting words are a quotation from Woolf’s last note to Leonard on 28 March 1941, before she walked into the river Ouse, her overcoat pockets filled with stones. Said note is cited verbatim in the Prologue of The Hours, which captures the scene of Woolf’s drowning. Even those oblivious to the manner of Woolf’s death must engage with Cunningham’s novel in the knowledge thereof, and are thus encouraged to approach Mrs Dalloway through that lens, though its composition precedes the suicide by nearly twenty years.[3]

The foregrounding of Woolf’s fate continues to trouble me, even if at every rereading of The Hours – and I have clocked two and a bit since December – I find that I love the novel more and more. The evocation of Woolf’s death, however sensitively and compassionately handled, can take us down a simplistic reading of this amazing, groundbreaking artist as a tragic figure. Virginia the victim. Virginia the troubled genius. Virginia the self-immolating martyr. Is it not enough to focus on her literary legacy? Isn’t that what we do, say, for Ernest Hemingway, that other master of (a very different kind of) modernism, who was a similar age to Woolf’s at the time of her death, when he shot himself in 1961? (Granted, with Papa Hemingway we’re generally too busy peddling biographical myths of another kind.)[4]

I am being deliberately polemical here and, I realise, unjust to Cunningham: The Hours speaks to Mrs Dalloway through meaningful connections that are never pedestrian or predictable, and open up new vistas on that work. But it’s also more than a homage, or a tricksy rewriting; it doesn’t simply sit on the shoulders of its source of inspiration, but speaks of its time (the AIDS crisis, or our obsession with celebrity culture) in a way that Woolf spoke of her own (the aftermath of WWI, or the weakening of those anchoring beliefs that had held fast through the Victorian age, such as religious faith, for example).[5] And it picks up from where Mrs Dalloway had paved the way in its multifaceted exploration of queer identity.[6] It is imbued with admiration for Virginia Woolf’s work, and Cunningham’s portrayal of her mental illness is prescient in raising awareness of an issue we are now much more used to discussing openly.[7]

What niggles me is the danger inherent in framing an entire life, and its creative output, in the context of suicide, a move that seems to occur more commonly in the case of female artists – Sylvia Plath is another case in point – and not so much for their male counterparts. And, yes, no doubt patriarchal attitudes have compounded these women’s suffering and mental health struggles, but there is something potentially, inadvertently reductionist about The Hours opening on 28 March 1941. Woolf’s suicide casts a shadow on what follows, presenting her entire life as a slow building up to that final gesture, with Mrs Dalloway itself becoming the symptom of a disease or, inexplicably, an achievement that flies in the face of that tragedy: “How, Laura wonders, could someone who was able to write a sentence like that – who was able to feel everything contained in a sentence like that – come to kill herself?” (More on the sentence in question anon.)

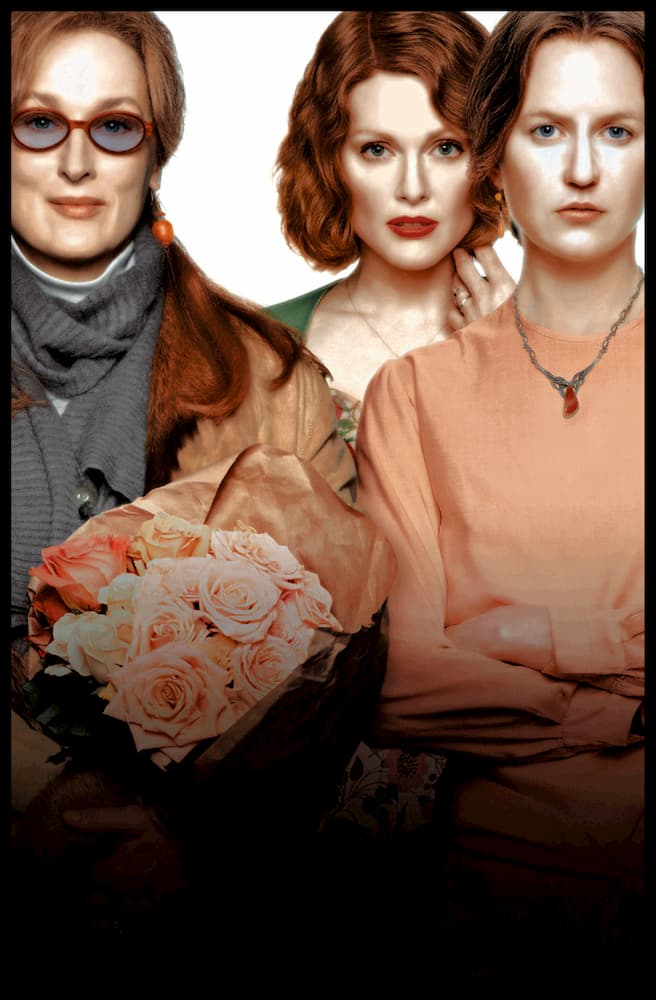

Meryl Streep, Julianne Moore and Nicole Kidman in ‘The Hours’

The opera handles this more subtly. Its first scene sees the chorus singing Mrs Dalloway’s famous opening, placing Woolf’s novel, rather than her drowning, front and centre. When Kelli O’Hara sings Laura’s heartache that a genius like Woolf could have killed herself, her lines blend into a duet with Joyce DiDonato’s Virginia, each declaring her determination to read in one case, write in the other “one more page” of Mrs Dalloway. For Laura, this is a losing oneself, for Virginia a finding oneself. In this evocation of Woolf’s suicide, the emphasis lands on the writer’s agency, and on her ability to reach out through time to generations of readers.[8]

The fact that Virginia/DiDonato can finish the sentence begun by Laura/O’Hara is an illustration of my initial point about the strength of opera, unconstrained by the inescapable linearity of the novelistic or the cinematic medium.[9] The converging and collapsing of different narrative strands regales us with an absolute gem of an ending, when DiDonato, O’Hara and Renée Fleming come together in an exquisite trio: “This is the world / And you live in it / And you try to be / And you try / And you try…”.

Having created three distinctive dimensions, musically and visually, as is fit for the specificity of these women’s experiences, the opera’s finale brings about a marvellous communion that transcends their individual circumstances: the singers sit holding hands, inhabiting the same physical and metaphorical space. It’s a space we are invited in as they move to the front of the stage for the final bars, the “you” of their shared reflection doing double duty as an interpellation of the audience. Joined in our humanity, in that unique and yet common endeavour that is the act of being in the world, we are not alone.

For me, this opera really captures the life-affirming quality that is the miracle of Mrs Dalloway. I used to teach Woolf’s novel for an undergraduate course on British writing between 1918 and 1939 called “Literature between the Wars”. One of the most underlined passages in my well-thumbed copy – a passage that I would parse with my students – is the one where Mrs Dalloway thinks of her own mortality, and which my marginal annotation in pencil describes as “Clarissa’s epiphany”: “Like a nun withdrawing, or a child exploring a tower, she went upstairs, paused at the window, came to the bathroom. There was the green linoleum and a tap dripping. There was an emptiness about the heart of life; an attic room. Women must put off their rich apparel. At midday they must disrobe. She pierced the pincushion and laid her feathered yellow hat on the bed. The sheets were clean, tight stretched in a broad white band from side to side. Narrower and narrower would her bed be.”

Clarissa then considers her feelings for other women, and the sexual attraction she sometimes experiences, like “a sudden revelation”. I can see myself skipping a few lines to talk with my students about the striking image with which Woolf describes these epiphanies: “Then, for that moment, she had seen an illumination; a match burning in a crocus; an inner meaning almost expressed. But the close withdrew; the hard softened. It was over – the moment.” The seminar discussion would seek to explore the connections between Clarissa and Septimus, his trauma, the medical establishment’s failure to support him, indeed the several failures in communication in the novel. I could go on. Mrs Dalloway is inexhaustible as a source of aesthetic, affective and intellectual riches.

What has lingered with me after my most recent encounter with the novel – twenty years after those classroom discussions, in the wake of my vicarious visit at the Met to see The Hours – is Clarissa Dalloway’s wonderful ability to give herself to life, her receptiveness to those instants of contentment, her alertness to the present, what feels to me like an openness – a hunger even – to the possibility of joy. Even, especially, because of the awareness that time is passing. I know I am projecting. I have just turned fifty myself. But then I think of the sentence that makes Laura wonder about Woolf’s genius, and I know I am not the only one to see that: “In the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment in June.” Have you ever read anything more exhilarating than that?

The Hours premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City on 22 November 2022, conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. It will return to the Met stage, with Renée Fleming, Joyce DiDonato and Kelli O’Hara reprising the roles they have originated, next May. Meanwhile, the recording of the performance I saw as a live relay at the cinema on 10 December 2022 is available to stream via the Met Opera on Demand service.

Those interested in learning more about this opera may wish to watch this Met Talk with the creatives and the cast, or they may wish to listen to Episode 210 of The Met Opera Guild Podcast, in which musicologist W. Anthony Sheppard offers an insightful analysis of this piece. Spoiler alert: both the talk and the podcast mention a key connection between two of the subplots which I have left undiscussed.

[1] There are other instances in the novel when various subplots cross paths, such as when Clarissa and Septimus hear the same car backfire, or when Peter Walsh, the suitor Clarissa rejected before marrying Richard Dalloway, sees Septimus and his wife Rezia in the street, or when Peter hears the sound of the ambulance that is carrying away Septimus’s body after his suicide.

[2] Dan is a veteran of WWII, of course; Septimus of WWI.

[3] Woolf did incorporate autobiographical elements in her novel: for example, Septimus hears a sparrow singing in Greek, a hallucination experienced by Woolf herself during one of her breakdowns. In The Hours, Virginia recalls having heard a flock of sparrows outside her window singing in ancient Greek; Richard too hears voices singing in Greek. In the opera, Vanessa’s children reprise in ancient Greek some key lines that Laura and Virginia had sung earlier: “This is the world, and you live in it, and you try to be grateful”. A variation on these lines occurs in the final trio, as I will discuss presently. These thoughts originally occur to Clarissa Vaughan in Cunningham’s novel; in my opinion, they capture an essential aspect of Woolf’s novel.

[4] For a brief, incisive discussion of Cunningham’s recontextualization of Mrs Dalloway within a biographical frame, see Michael H. Whitworth’s Virginia Woolf in the Oxford World Classics ‘Authors in Context’ series (2005). Much like the novel and the film The Hours, Wayne McGregor’s 2015 ballet Woolf Works, whose revival I saw at the Royal Opera House in February, foregrounds Woolf’s drowning. Even Neil Bartlett’s 2022 theatrical adaptation of Orlando, which I saw at the Garrick Theatre in January, manages to reference the author’s suicide.

[5] On her way to buy flowers from Barbara, Clarissa Vaughan notices a movie being shot in a nearby street. A while later the two women hear a “huge shattering sound” coming from the film set and, when they see a “famous head emerg[ing] from one of the trailers”, they wonder who the celebrity may be. (Funnily enough, one of the hypotheses is Meryl Streep, who will play Clarissa Vaughan in Daldry’s film.) In Woolf’s novel, Mrs Dalloway, Septimus and other passers-by are startled by a car backfiring; the vehicle’s mysterious passenger is speculated to be royalty, or maybe the prime minister. The glamour of showbusiness is the late 20th century counterpart of the power of the ruling classes. Meanwhile, an aeroplane is writing an advertising message in the sky; technology and marketing seem to have replaced God above. Interestingly, Miss Kilman, the older woman to whom Mrs Dalloway’s daughter Elizabeth looks up, is presented – through Clarissa’s perspective – as a religious zealot. In Cunningham’s novel, Mary Krull – Miss Kilman’s equivalent – is an academic, “lecturing passionately at NYU about the sorry masquerade known as gender”. Both Clarissa Dalloway and Clarissa Vaughan are at odds with the religious / intellectual intransigence of their respective antagonists.

[6] As already mentioned, in Mrs Dalloway, we read of Clarissa’s kiss with Sally, and of her attraction to other women. Septimus’s devotion to his commanding officer Evans, who had been killed in action, can also been interpreted as underpinned by homoerotic desire.

[7] The focus on mental health in The Hours has come up in interviews with the cast of the opera as giving a topical edge to this work in our post-pandemic world.

[8] The suicide is also evoked in the costumes of the chorus, which are streaked with what look like ripples of water. The chorus accompany Woolf, stones in their overcoats, in what is the most overt allusion to her drowning. However, this final scene in the narrative strand specifically devoted to Woolf does not close the whole opera. The film adaptation instead ends with Woolf’s suicide: Nicole Kidman’s voiceover as Woolf accompanies rapid cuts between her story, and Laura Brown’s and Clarissa Vaughan’s, played by Julianne Moore and Meryl Streep. In the voiceover, Woolf is mentally expressing her gratitude to Leonard for the life they have spent together. We then see Kidman walking into a river, in what is inevitably a much more realistic rendition of the suicide than what is possible on stage. Daldry’s The Hours thus comes full circle, since it also opens with the suicide, in what is effectively a cinematic representation of the Prologue in Cunningham’s novel.

[9] Director Phelim McDermott has talked of the challenge of staging The Hours as having to put on three different operas at the same time. (McDermott and his collaborators pull this off with flair, through movable sets and a signature colour palette and recurrent images for each of the women: Virginia’s world is full of books, Laura’s full of domestic objects, and Clarissa’s full of flowers.) On the other hand, opera must condense, more than film, in adapting even a short novel like The Hours. The result is something more pared down than Cunningham’s work but, like all successful distillations, more intense too. For example, Clarissa’s daughter Elizabeth is completely excised by the narrative; in fact, Clarissa doesn’t want to have children, while her partner Sally does. This creates a further connection between Clarissa’s and Laura’s story.

Main image: The Metropolitan Opera House, New York City. Credit: Russell Kord / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Renee Fleming, Joyce Didonato and Kelli O’Hara on a promotional poster for The Hours

Image 2: Taken at Virginia Woolf’s last formal photography session in 1939, taken by Gisèle Freund and the only pictures of Woolf in colour. Credit: Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3: Bust of Virginia Woolf in Tavistock, near the house where the above photograph was taken. Credit: Robert Evans / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4: Meryl Streep, Julianne Moore and Nicole Kidman in the film version of The Hours. Credit: TCD/Prod.DB / Alamy Stock Photo

Our paperback edition of Mrs Dalloway, for £3.99, can be found here, and our Collector’s Edition hardback for £8.99 here

Books associated with this article

Mrs Dalloway (Collector’s Edition)

Virginia Woolf