Woolf Works

Wayne McGregor and the Royal Ballet re-imagine Virginia Woolf and her work – Sally Minogue reviews.

‘Wow!’ Sometimes the finely tuned word won’t do, and that was the only sound that came out of my mouth after the first act of this ballet triptych in homage to Virginia Woolf. By the end – no words, but tears.

My astonishment at the brilliance of this tribute by one art form to another signals a gap in my cultural understanding that I’m rather unwilling to concede. I’ve always thought that I enjoyed the ballet. I went to the famed Bolshoi Ballet performance in a big tent in London in 1986, with Irek Mukhamedov astonishing us with his leaps, and the corps de ballet with their equally famed arms shimmering in brilliant unity. Before that, I’d worshipped Nureyev (another leaper), and one of my school prizes – then a rather daring choice – was a book of photographs of him in his balletic glory. I still have it. Even earlier, I’d watched Royal Variety performances on the television with my Mum and Dad, in which there was always a serious bit, and that serious bit was ballet – usually a pas de deux. Being at that time a young person who thought she ought to like that sort of thing, I thought I liked that sort of thing. And we all knew about Margot Fonteyn, our own British ballerina. In later years, I progressed (and that is how I would have thought of it) to Ballet Rambert. There was an unforgettable performance of The Rite of Spring by the Pina Bausch company at Sadler’s Wells – but I didn’t realise just how lucky I was to be watching this iconic dance company until the young man next to me, at the curtain call, started hollering ‘Pina! Pina! Pina!’ – as, in a different time and place, one might have cried ‘Ooh! Aah! Cantona!’ Most recently, I’ve had genuine pleasure in the company of my great-nieces, watching Northern Dance’s Peter Pan and The Nutcracker – superbly theatrical, witty and engaging, and combining technical aplomb with great musicality.

But seeing this revival of Woolf Works by the Royal Ballet (originally performed in 2015) – albeit in a Live Relay performance rather than in the flesh – I realised perhaps for the first time what dance can do. I say dance because Wayne McGregor’s work combines elements of both contemporary dance (probably no longer the right term) and classical ballet, but ‘dance’ doesn’t seem the right term either. This was the human body used as an expressive material, almost as a sculptor might use clay, except that this was living to clay – the mind, the heart, the breath, the muscle, even (as Darcey Bussell, introduces each of the three ballets, said, and she would know), the ligaments and tendons.

The pre-eminence of the body, and the extraordinary things dancers at the peak of their training and experience can do with it, are central to the power and vitality of this work but also to its poignancy. The dancer at its heart, embodying the older Virginia Woolf and also, in the first ballet, Mrs Dalloway, is Alessandra Ferri, herself in her very early fifties, only years away from the age when Woolf took her own life. Ferri takes centre stage in the first and last ballets, ‘I now, I then’ (based on Mrs Dalloway) and ‘Tuesday’ (which combines Woolf’s life with the spirit of The Waves). In the middle ballet, ‘Becomings’ (based on Orlando) the figure of Woolf is absent and free rein is given to the workings of her imagination in that extraordinary novel. In ‘I now, I then, the Royal Ballet’s principal dancers embody the earlier/younger Woolf/Clarissa Dalloway so that there is an interplay between past and present, memory revivified in dance through younger bodies, but with the older Ferri herself revivified as she dances alongside and in partnership with possibly her younger self or her younger creation, Clarissa, and younger partners both male and female. We go back in time as the dancers’ bodies become suppler and more lyrical but there is never a judgemental comparison, rather they interweave with each other in a dance that defeats time. Memory as Woolf herself conceived it is captured by the simple set of massive wooden frames – one might say photograph frames but that would be too clumsy – which provide a threshold between periods of time. Dancers/characters remain on stage, contemplating from these frames as other dancers/characters/selves take centre stage. Memory is enacted but also brought into the present, but then as swiftly dropped back into its own time frame.

This first ballet is the most faithful to its originating fiction, perhaps because Mrs Dalloway has a clearer narrative structure (though McGregor in the interview accompanying the live relay suggested that when one works with the human body in dance, it is always and essentially a narrative medium). Here he showed us Mrs Dalloway/Woolf, briefly placed in time in 1920s London, going back into the memory of Clarissa’s kiss with Sally in the garden of their youth – perhaps the formative moment of her life. Video projection, here as throughout, cleverly allows past images to enter the present, with the dancers emerging from and merging into the modern version of a backcloth. Happy innocence pervades this early part, which is genuinely joyful – I can’t remember when I’ve seen dancers look so happy. But if we know our Woolf, we know what is to come. The Spring garden is gone; and here is Septimus in agony, with the dead Evans standing sentinel in the tin hat in the background. The effect is almost Biblical – the anguished Septimus in his spiritual wilderness. This is the emotional core of the piece. The choreography changes from suppleness and lyricism to wrenching and unpredictability. Septimus’s body (principal dancer Edward Watson) is turned this way and that, it feels not of his own accord, the only relief coming in his gravely tender duet with the dead/alive Evans. This, along with Evans’ frenzied pirouetting at the limits of the stage (a maddened version of a ballet convention), caught afresh me the deep sadness of the First World War.

It was going to be hard to follow this first act, and for me, the central section, ‘Becomings’, disappointed me both as a dance and as an interpretation of Woolf. I refer my readers to my review of the Manchester Royal Exchange adaptation of Orlando which was masterly – or perhaps, mistress. But I could see that in this middle section the dancers were put to a full test, their bodies stretched almost shockingly. The costumes – rich gesturing to the 16th century, witty vinyl-like tutus on men and women – emphasised androgyny as befitted Woolf’s playful material. Without knowing his work except for this ballet, I suspect this was McGregor’s favourite section; but for me, with its coloured lasers and dressing-up outfits, it felt like an 80s Berlin techno club with the Royal Ballet let loose on a night off. But quite obviously – what do I know?

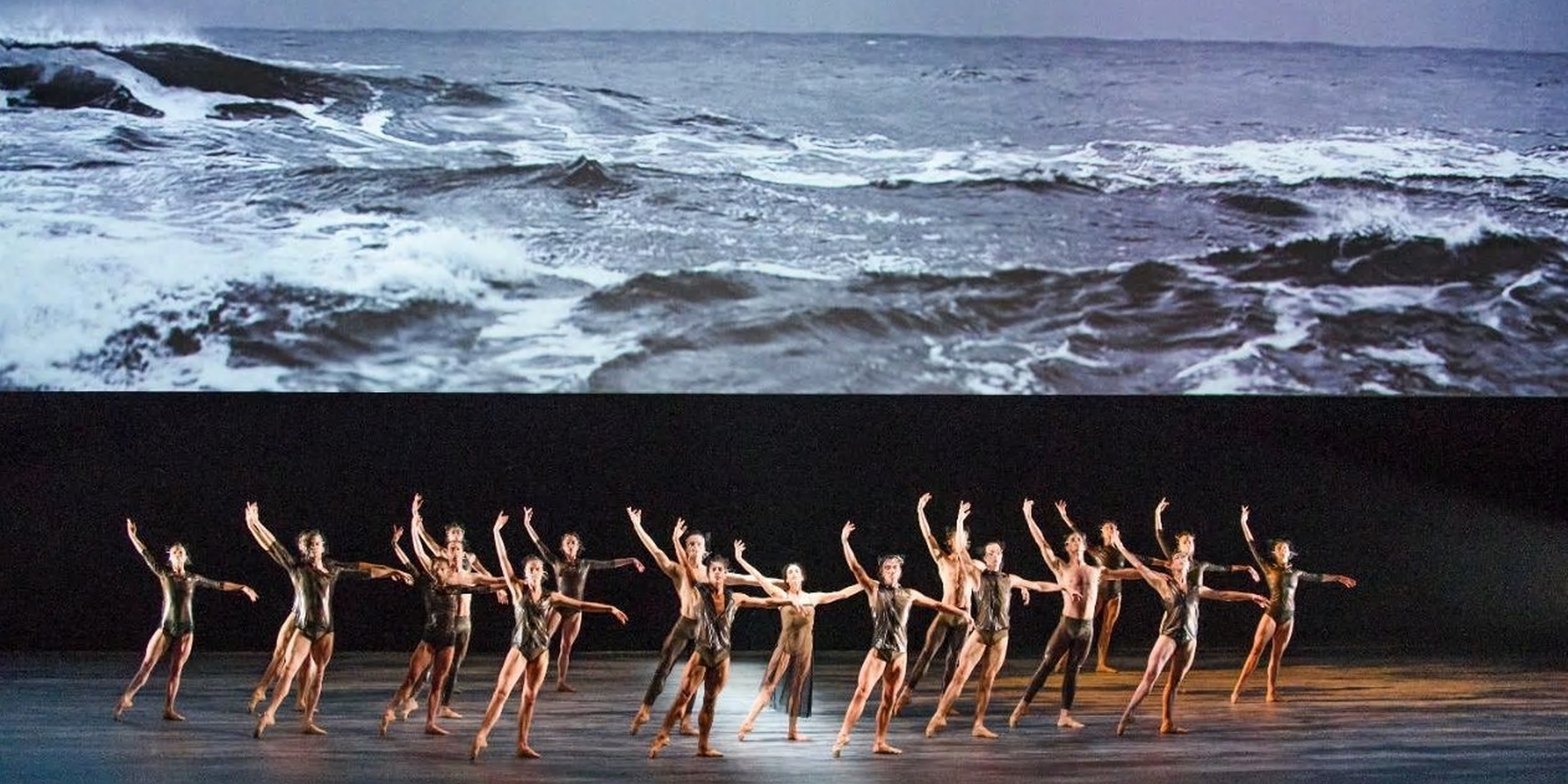

What I do know is that Wayne McGregor knows his Virginia Woolf (aided in this by the core contribution of dramaturge Uzma Hameed). The whole of this ballet was instinct with an understanding of Woolf’s person and her work, and it showed the irreplaceable beauty of a collaborative artistic performance through which that understanding permeates, even to the level of the young Royal Ballet School students who performed in the final, and again deeply moving, section, ‘Tuesday’. This began with a reading, by Gillian Anderson, of Woolf’s suicide letter to Leonard, headed simply ‘Tuesday’. It is heart-breaking, but the dance which follows – a glorious ensemble piece in which there is a sense both of communality and individuality – contains all the elements of Woolf’s personal and creative life, and achieves a sense of celebration of that whilst never denying the accompanying distress and final tragedy. Like Septimus, she wishes to fear no more, and like him, she gets her wish. Throughout, the upper half of the backdrop, plays a video projection of great waves breaking in slow motion, the waves Woolf herself alludes to in her memories of lying as a child in the holiday house at St Ives. The waves then were comforting; in memory, she calls back that comfort. In the novel The Waves, they become the waves of consciousness, lying outside time. In the ballet, the waves inexorably break, looming over the frail bodies of the dancers, ready to engulf them. Woolf herself could not have imagined a better metaphor.