The Life and Works of Dylan Thomas

As Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog are published by Wordsworth, Sally Minogue fills in the background.

Dylan Thomas’s best-known and best-loved work, Under Milk Wood, is the principal text in this volume. Dylan Thomas’s self-styled ‘play for voices’ is the last mature work to come from his pen; he was still revising it on the run, having fresh copies typed as he changed the words, for the performances in America in both May and October 1953 in which he himself took the part of First Voice. The work has become inextricably linked with his early death only weeks after that October performance, in a New York hospital far from home. There was not even a definitive final manuscript. The first radio broadcast of the play took place six weeks later, on January 25th 1954, and was an instant success. The young but already famous Welsh actor Richard Burton, with his richly beautiful vocal delivery, took the part of First Voice, and the play brought an entirely fresh approach, interweaving voices and highly poetic narrative to create a word-picture of twenty-four hours in the life of a small but bustling Welsh coastal village, Llareggub.

The new Wordsworth edition of ‘Under Milk Wood’

Under Milk Wood had a long gestation, the very first conception of it appearing in a short story he read to his old Swansea comrade Bert Trick in 1933; Trick recounts that ‘the story was then called Llareggub, which was a mythical village in South Wales’. So do great works have their first seeds. The schoolboy joke of the name ‘Llareggub’ (‘bugger all’ backwards) remained the one constant in a work that had many stages and revisions over the 20 years to its fruition. (It should be said that there are various spellings of this name in various places, and in the text itself Thomas uses ‘Llaregyb’ because it looked and sounded more Welsh.) The radio script ‘Quite Early One Morning’ (1945) opened in a similar way to the eventual radio play and nodded to some of its characters. In 1950 a version of the first half of the play was submitted formally to the BBC under the title ‘The Town that was Mad’. And in 1951 Thomas submitted a version of this first half for possible publication in Botteghe Oscure, an Italian periodical recently founded by Marguerite Caetani (an index of Thomas’s European leanings). Thomas sketched in to Caetani the way the work was to develop, and as he was writing persuasively to his potential editor, we have an unusually full account of Under Milk Wood as a work in progress. It would feature ‘all the activities of the morning town – seen from a number of eyes, heard from a number of voices – through the long lazy lyrical afternoon, through the multifariously busy little town evening of meals and drinks and loves and quarrels and dreams and wishes, into the night and the slowing-down lull again and the repetition of the first word: Silence’. There couldn’t be a better characterisation of the eventually completed play. The only part missing was the night-time and dawn sequence already there in the first half he was sending, which was published in Botteghe Oscure in April 1952.

Douglas Cleverdon, the BBC producer who had worked regularly with Thomas, nurtured the last stages of the development of the play and indeed rescued the final extant manuscript just before Thomas left for his last trip for America, the author having left it in a Soho pub. Cleverdon worked in the Features department of BBC radio where many of Thomas’s broadcasts originated, and he maintained that this influenced the writing of Under Milk Wood considerably. Under the aegis of Drama it might have been straitened by generic and historic considerations, whereas Features already had a tradition of fluidity and openness of form and technique. ‘Narrative, dramatization, actuality, documentary, verse, song, music, electronics, sound effects’ – these were for Cleverdon the multi-dimensional materials of Features. We find them all in Under Milk Wood, woven together by Thomas’s brilliant use of language and an imagination which flows in and out of the external and internal worlds. His ‘play for voices’ generously represents the range of human experience in a way that remains fresh today.

Under Milk Wood has a comic spirit and this makes it an essentially optimistic text, exploring the human comedy of which we are all part, necessarily including elements of pathos and tragedy, balanced by a corresponding compassion. In that way it is like Shakespearean comedy, which takes us into a semi-illusory world where things are often turned upside down and then righted again. This is a fundamentally beneficent universe, where even the lonely Bessie Bighead, ‘born in a barn, wrapped in paper, left on a doorstep, big-headed and bass-voice’ is briefly illuminated by the play. And in ‘the White Book of Llareggub’ (a nod to the early manuscripts which were part of the founding culture of Wales) ‘the one poor glittering thread of her history [is] laid out … with as much love and care as the lock of hair of a first lost love’. In Under Milk Wood then Thomas shows us that the lives of even the humblest of individuals have worth. By contrast anyone with pretensions is punctured. Yet even the local aristocrat, skewered by his name Lord Cut-Glass, is shown as endearingly eccentric as he ‘squats down alone to a dogdish, marked Fido, of peppery fish-scraps and listens to the voices of his sixty-six clocks, one for each year of his loony age, and watches, with love, their black-and-white moony loudlipped faces tocking the earth away’. Bessie Bighead and Lord Cut-Glass are not so far from each other. Of course much of the comedy of the play comes from the way Thomas lays bare the inherent weaknesses and foibles of his characters, but that ‘with love’ is always there. Dylan Thomas

Statue of Captain Cat, Swansea Docks

Of the 65-plus characters and voices in the play (a number are anonymous, or stand as groups), certain ones are pivotal. Polly Garter opens her arms to all manner of men in Milk Wood, but keeps her heart for little Willy Wee who is ‘dead, dead, dead’; Captain Cat is the constant onlooker, viewing events from his ‘ship-in-bottled, shipshape best cabin of Schooner House’; Willy-Nilly postman goes from house to house giving people their news before he delivers the letters (and so is also a useful narrative device). The two Voices, First and Second, are the omniscient narrators, ever present to fill in the action, to introduce characters, or to take us into their inner consciousness. Then there are multiple couples. Myfanwy Price and Mog Edwards play out their romance at a distance from one end of the town to the other, with Willy-Nilly as intermediary. Mr Pugh is constantly planning to murder Mrs Pugh, in as horrible a manner as possible (Willy-Nilly reports that he has just delivered to him Lives of the Great Poisoners). But his deadly desires may be as phantom and unfulfillable as the delicate Gossamer Beynon’s lust for Sinbad Sailors. Much of what Thomas shows us of the inner selves of the people of Llareggub are dreams of that kind, and even when they are expressed, as in the letters of Myfanwy Price and Mog Edwards, they are not acted upon. The threnody underlying these lived lives is provided by the voices of the dead, the Drowned who open the play, and Rosie Probert who is the double of Polly Garter (‘Come on up, boys, I’m dead’). In the way of the play with its constant ebb and flow of voices, no distinction is made between living and dead, which gives us a sense of past flowing into present and vice versa. Captain Cat is more at home amongst the Drowned, removed as he is in his eyrie looking down. And holding it all together is the all-seeing First Voice, who begins and ends the play in darkness and: Silence. Dylan Thomas

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, a collection of short stories linked by the central narrator/subject, is the companion piece in this volume. By contrast with Under Milk Wood it is an earlier work, but a mature one. These stories were written in a concentrated period of time between March 1938 and September 1939. Thomas had written and published short stories before, but this collection marked a change of style and a new maturity, as Thomas drew on his own early life to reflect not just on that, but on the whole business of how we write about our past selves. While the writer’s own early life and his growth into adolescence and adulthood are the central inspiration and subject matter, he used these as a jumping-off point to explore universal thoughts and feelings. These stories were written when the author was at a relatively settled period in his life. He had been married to Caitlin Macnamara in July 1937; they settled in Laugharne, Carmarthenshire in April 1938; their first child, Llewellyn was born in January 1939. Thomas’s belief in the importance of his writing had been confirmed by early success with his poems, his first collection 18 Poems published in 1934 and his second, Twenty-Five Poems, in 1936. His commitment to writing full-time meant that he was chronically poor, as are many artists in their early lives. But he and his family received lots of support from those who valued his work, and this period in Laugharne was relatively comfortable. In this environment Thomas worked at full pitch on the stories for this new collection. He wrote, again to Bert Trick, that they were ‘stories towards a provincial autobiography. … They are all about Swansea life: the pubs, clubs, billiard rooms, promenades, adolescence and the suburban nights, friendships, tempers, and the humiliations’. This reminds us of his letter about Under Milk Wood to Caetani: the multiplicity and variousness, the sense of excitement about his projected writing, the emphasis above all on the ordinary. And yet the stories in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog are far from being only ‘all about Swansea life’. This is the one thing Dylan Thomas does in all his writing. He draws on the local, the particular, the ordinary; but he seamlessly moves from that to what lies beyond.

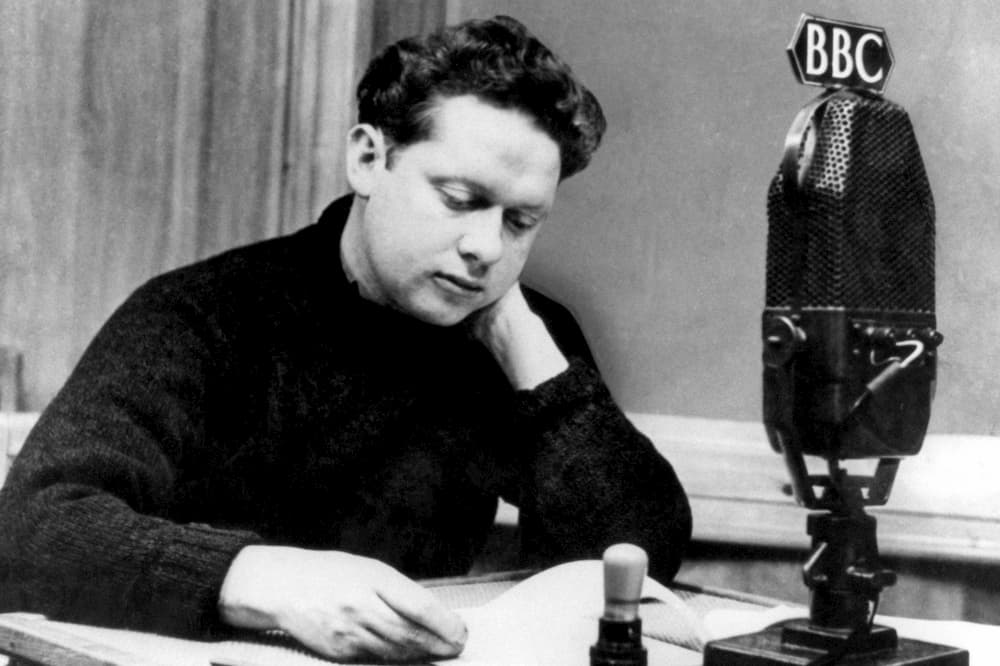

Dylan Thomas at the BBC

There are ten stories in the collection, and seven of these are written in the first person, thus involving the reader directly with an individual consciousness. Thomas’s title, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, seems to refer overtly to James Joyce’s novel, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Thomas denied any influence by Joyce on the title or the collection; one can only think he was deceiving himself. But there is no problem with such an influence. Thomas draws on Joyce (especially his short story collection Dubliners) as a model, but is completely original in his own writing on similar subjects. He extends the Joycean tradition rather than copying it. What Thomas adds is a sense of joy. His stories are infused with a pleasure in living, in landscape, in the imagination, in moments of epiphany – yes, like those of Joyce but optimistic rather than pessimistic. Stories to look out for particularly here are the first one, ‘The Peaches’, a master-class in the short story; ‘Patricia, Edith, and Arnold’, those very commas telling a tale of a triumvirate of lovers; and ‘Old Garbo’, with its insight on old age, the insistent power of enjoying life, and an almost unnoticed sadness. But the best way to read this collection is from beginning to end, following the development of the protagonist from child to young adult.

Many of the stories are centred on Swansea, where Thomas was born and grew up, the ‘lovely, ugly town’ as he described it. This gives a realist base for the subsequent flights of fancy the narrator takes at times. In a similar way Under Milk Wood was loosely based on both New Quay, where Thomas developed it, and Laugharne, where he completed it. At one time or another in the stories we are taken beyond the realist confines and into an imagined world, just as we are in Under Milk Wood. This is perhaps the quality that most marks Dylan Thomas’s writerly imagination, and which links the two works in this volume. Although Under Milk Wood and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog have in common that they are both set in Wales, they range far beyond that. Dylan Thomas

Thomas had a complicated relationship with the country of his birth; when he left it to try his luck in London for the first time he reputedly said: ‘The land of my fathers; my fathers can keep it.’ But this belied what was in fact a deep connection. He constantly returned to Wales, wrote much of his best work there, and took inspiration in particular from its landscape, and from the sea which embraced it. But Thomas was in no way a parochial writer, and certainly not a nationalist one. He did not speak Welsh, but in any case at that particular cultural moment, English would have been his choice of language as a writer. His impulse was always to cross borders, he was international in his thinking, and he found a wide audience, most notably in America. Both Under Milk Wood and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog may have their roots in his native culture, but their vision is universal.

Grave of Dylan Thomas, St Martin’s Church, Laugherne

Dylan Thomas died in 1953 at the upsettingly young age of 39. Indeed he was only just 39, as his birthday was October 27th 1914 and he died on November 9th 1953. These are the bare facts of his birth and death, but between those dates Thomas squeezed in a rich and complicated, and sometimes problematic, personal life, and a hugely productive writing life. Dying at 39 would be unhappy for anyone. But dying so young when one has already produced a large body of writing, and been recognized as an important artist, brings in another dimension – the work that might have been written, which is lost by that death. Thomas, had he lived, might have expanded his writing in several different directions. He left behind him a large, wide-ranging body of work and unusually he excelled in several different genres. This volume reflects two of those genres, the radio play and the short story. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog has a claim to be one of the significant story collections of the twentieth century. The radio historian Peter Lewis said of Under Milk Wood on its 25th anniversary that it was ‘the most celebrated full-length play for radio … that the BBC has produced in more than fifty years of broadcasting’. In March 2024, his Collected Poems will be published by Wordsworth. It is now for current readers to judge these works as we look at them from a 21st century position. But to my mind, the boy from Swansea done good.

For more information, visit: http://www.dylanthomas.com/

Our editions of his work can be found here

Main image above: New Quay in Wales, the inspiration for the village of ‘Llareggub’. Credit: Keith Morris/Alamy Live News/Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Our edition of Under Milk Wood

Image 2 above: Statue of Captain Cat, Swansea Docks. Credit: Mauritius Images GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Thomas at the BBC. Credit: CPA Media Pte Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Thomas’s grave, St Martin’s Church, Laugherne. Credit: Bill Robinson / Alamy Stock Photo

XXX

Dylan Thomas

Books associated with this article

Under Milk Wood

Dylan Thomas