Sally Minogue looks at Under Milk Wood

As Wordsworth prepares to publish Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog in January 2024, Sally Minogue gives us a foretaste of the pleasures they will afford for readers.

Seventy years ago this November, Dylan Thomas died a deeply distressing and horribly early death in a New York hospital thousands of miles away from his native Wales. That seventy years distance means that his work now comes out of copyright, which affords us the opportunity to look at his work afresh and in a more objective light. Though he was only 39 when he died, Thomas left behind a quite remarkable, large and wide-ranging body of work. We think of him principally as a poet, but he was unusual in that he excelled not just in that field but also in the writing of short stories, and of a unique radio play, Under Milk Wood.

Dylan Thomas directing Under Milk Wood

Under Milk Wood is Thomas’s last major work; he was still revising it in the months before his death, and took the role of First Voice in New York just two weeks before he died. The play had not yet even been published when it was broadcast on the radio in Britain as a tribute to Thomas in a now-famous production (January 25th 1954) with rising star Richard Burton taking the role of First Voice. It had always been intended as a radio play – a ‘play for voices’ as Thomas himself dubbed it – and it was an immediate popular success. Because it is written in a non-visual medium, relying on the power of the words themselves to paint a picture through First Voice’s narrative and the voices of the characters themselves, as readers we can join Thomas’s vividly conjured world and share his imagination. We are aided in this by the structure of the play, with First Voice setting the scene, and the subsidiary Second Voice leading us into the minds, hearts and lives of a multifarious set of characters. They weave in and out of each others lives, and that of the reader, some taking small parts, some lead characters who recur through the play, and some simply a chorus of anonymous voices. These latter – the Drowned, the Neighbours, the Women, and later the voices of children – act rather as a Chorus in a Greek play would have done, providing a commentary which lies as a backdrop and counterpoint to the named voices that are given more prominence.

The play takes place over a notional 24 hours, and again like Greek drama it observes the unities of time (the aforesaid 24 hours), place (here the Welsh village of Llareggub which lies under Milk Wood) and action (one continuous narrative starting in night-time darkness and moving through the day towards night again). This produces a powerful concentration and distillation, but at the same time there is a floating quality about the movement of the play. As one voice takes over from another, a rhythm arises which carries us lightly above the action, which is anyway largely internal. Thomas takes his cue from the tidal rhythms of the waters that surround Llareggub (and which lapped the shores of Laugharne and New Quay, the two Welsh towns where he lived and on which he based the play). After the narrating First and Second Voices, the first characters we hear from are the Drowned, speaking from the dead to Captain Cat as he plumbs the depths of his own memory from ‘the sea-shelled, ship-in-bottled, shipshape best cabin of Schooner House’. The distance between past and present is eclipsed, and the dead seem as alive as those we go on to meet on the streets of the small town, for example Polly Garter who grows ‘nothing … in our garden, only washing. And babies’. The very-much-alive Polly and the dead Rosie Probert (‘Come on up boys, I’m dead!’) have a sexual generosity which stands for a larger warmth and magnanimity. Indeed, generosity might be the watchword of the play.

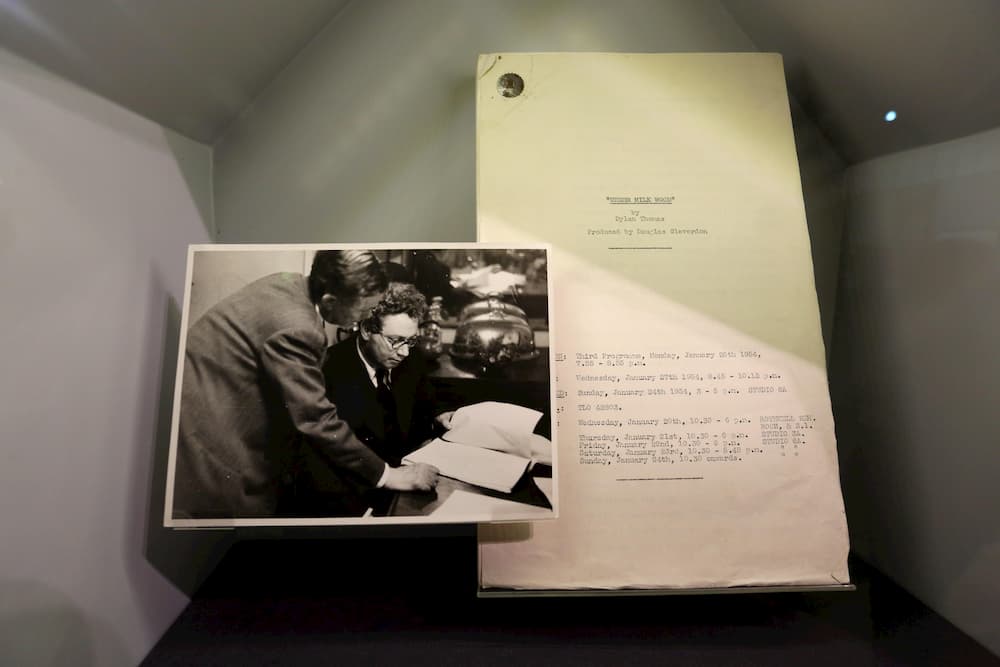

The transcript of Under Milk Wood

It is written in a comic spirit, so that even where there is an undertow of tragedy, a sense of the ridiculousness of the human condition comes through – though characters are never laughed at, but laughed with. Mog Edwards and Myfanwy Price live at the opposite ends of Llareggub; they conduct a passionate love affair in letters, and always at a distance – even though one or the other could walk up or down the hill and meet to fulfil the fantasies expressed in their letters. These include Mog’s touchingly domestic ‘I will warm the sheets like an electric toaster, I will lie by your side like the Sunday roast’. The same spirit pervades Thomas’s collection of short stories, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, published on the eve of the Second World War. These are semi-autobiographical stories based on Thomas’s childhood and adolescence in Swansea, and his regular visits to his aunt’s farm in Carmarthenshire, the latter providing a pastoral dimension to set against the incipient urban gloom of the Swansea stories. Thomas spent his life up to the age of 20 living in or based in Swansea, the ‘ugly, lovely town’ as he described it in his nostalgic broadcast ‘Reminiscences of Childhood’ for the Welsh Home Service in 1943. In the stories he evokes beautifully the life and detail and even the geography of a well-known place and time. Yet these stories can, I think, be placed on a par with James Joyce’s Dubliners (similarly partly autobiographical, and capturing a specific place and time) since they speak of and to the universal themes of the human heart. They are similar too in that each collection follows a trajectory from childhood to adulthood (in Joyce’s case ending with death), so that there is a sense of linked narrative from one story to the next. This is more thorough-going in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, where seven of the ten stories have a first-person narrator, a character who also figures in the other three, but objectified and put at a distance by the third-person narrative. Thomas himself is identifiably the model of this central character, but he is unfussed by issues of historical accuracy, sometimes giving his characters the same names as actual people who were part of his life, sometimes giving them a fictional name and status. The stories are based on reality, but they contain such flights of imagination that they also feel experimental at times. In the true tradition of modernism, Thomas enters the consciousness of his characters, and from there he leaps off into worlds both past and future, often hyperbolic, sometimes comically so, but always linked to a fully realized actual world.

The new Wordsworth edition of ‘Under Milk Wood’

There are moments of tragedy in these stories too. ‘The Peaches’ turns on the clash of two worlds, as the young Dylan’s friend Jack visits the family farm where Dylan is spending his holidays. The world of the farm is threadbare in monetary terms, but rich in both love and eccentricity, and its beautifully evoked landscape carries a wild freedom for the young boys. But the arrival – in a Daimler! – of Jack with his mother ‘fitted out like a mayoress or a ship’ upends the natural order of goodness that Aunt Annie represents. The Daimler world is really the paltry one, but it is poor Annie who feels worthless at the end of the encounter, her quiet crying only half-heard and half-understood by the boys eavesdropping from their beds above the kitchen. Thomas is a master of restraint in evoking such heart-aching moments.

The keynote of these stories, however, is a resounding joy in life, much as it is in Under Milk Wood. There is often a brief epiphany at some point in a story where the central character feels himself ‘in the snug centre of my stories’ (‘The Peaches’), rapturously at home with himself and with the world. There is something enormously enjoyable at the heart of these stories, in part because they focus on childhood and youth, where there is still an unmarked optimism and appetite for life. The exuberance of the language can carry us away into the world of imagination, but it can also celebrate the ordinary world in which these stories are based. There is a determined openness of spirit and a marked lack of judgementalism, just as in Under Milk Wood. In that play, human frailty is seen as part and parcel of the human endeavour, and as the Reverend Eli Jenkins says in his ‘sunset poem’ as we draw towards the end of the play, ‘We are not wholly bad or good/ Who live our lives under Milk Wood’ (the one time those titular words are used in the play). Or as Polly Garter puts it, in a different way, ‘Isn’t life a terrible thing, thank God?’ Thomas is at his best when shining a brief loving light on the ordinary or the neglected in the world, as he does both in his radio play and in his stories.

This volume then encompasses, in two different genres, the movement of life from childhood to adolescence in the stories, and the span of a day in the existences of a whole lifetime of people in the radio play. Both genres are inherently optimistic, comic in spirit, but allowing into their tidal rhythms the tragic undertow of existence – as all good comedy should. In these pages readers will meet ordinary people, speaking in their own words. They will laugh at the human comedy, and be moved by the mis-steps and frustrations of desire as it struggles with the fear of declaration or the failure of concealment. Most of all, they will be engaged, just as the writer Dylan Thomas was, with the ways in which a vividly experimental language can express the complexities of the human heart and mind. Seventy years on from his death, Thomas’s own rich and extraordinary voice speaks to us still – the best sort of immortality.

Dylan Thomas’s actual voice can be heard on the remarkable Caedmon recordings which began with his performance of First Voice in Under Milk Wood on his penultimate visit to New York. The complete Caedmon recordings, which have all of Thomas’s recorded work including readings of his own poems and those of others, and of his stories, are cheaply available and they are an extraordinary resource for anyone interested in his work. The Caedmon Collection, Caedmon/HarperCollins, 2002

The original BBC broadcast of Under Milk Wood, January 1954, can be found on The Essential Dylan Thomas, Naxos AudioBooks, 2005, with interesting liner notes about the context of that broadcast.

www.dylanthomas.org is the online presence of all things Dylan

Our new edition is here: Under Milk Wood – Wordsworth Editions

Main image: View of Dylan Thomas’s writing shed in the town of Laugharne. Credit: Aled Llywelyn / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Dylan Thomas directing Under Milk Wood. Photographer: Rollie McKenna. Credit: Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: The transcript of Under Milk Wood on display at the Dylan Thomas Centre 2014. Credit: D Legakis/Alamy Live News

Image 3 above: The new Wordsworth edition

Books associated with this article