Stephen Carver looks at Vanity Fair

‘A great quantity of eating and drinking, making love and jilting, laughing and the contrary, smoking, cheating, fighting, dancing and fiddling’: Life in ‘Vanity Fair‘

Sometime between 1845 and 1846, the literary journalist William Makepeace Thackeray (1811–1863) drafted a few short pieces entitled Pen and Pencil Sketches of English Society (illustrated by himself), which he hoped would constitute the opening chapters of an as-yet unspecified longer work. ‘The truth forces itself upon me,’ he wrote to his friend William Aytoun (half of ‘Bon Gaultier’), ‘now is the time, my lad, to make your A when the sun at length has begun to shine. Well, I think if I can make a push at the present minute, I may go up with a run to a pretty fair place in my trade.’ With a kind of desperate optimism, he viewed the proposed project as a way to break out of the low-paid hell of blue-collar writing and achieve the same level of success as his friends Dickens and Ainsworth, and his enemy Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Thackeray was 35, and as his early biographer Lewis Melville was forced to admit, ‘the undisputed fact remains that in 1846 Thackeray was unknown outside literary circles and his own intimate friends.’ Thackeray was by then the father of two surviving daughters (a third, Jane, had died before her first birthday), and his wife Isabella had fallen into the chronic mental ill-health that would dominate the rest of her tragic life. Although born of a good family and privately educated (Charterhouse and Cambridge), he had lost a significant portion of his inheritance to professional gamblers while a student, the last of it going through the Agency House Crisis in Calcutta when the Bank of Hindoostan collapsed. (As an Anglo-Indian, Thackeray’s remaining patrimony had all been tied up in Indian investments.) Desperate to support his family, he was, as he often told his friends, ‘writing for his life’. He offered the new project – now provisionally entitled A Novel Without a Hero – to the publisher Henry Colburn for inclusion in the New Monthly Magazine, for which he already wrote comic sketches, alongside his frantic freelance contributions to Fraser’s Magazine, the Morning Chronicle, the Foreign Quarterly Review, The Times, and Punch. Colburn took one look at it, saw nothing new, and turned it down.

The Sketches were duly shelved, but not forgotten, while Thackeray began to finally make a modest name for himself writing ‘The Snobs of England, by one of themselves’ – later The Book of Snobs – for Punch. While engaged in this enterprise, a revelation struck. As he wrote to his friend Kate Perry: ‘I jumped out of bed and ran three times around my room, uttering as I went: Vanity Fair! Vanity Fair! Vanity Fair!’

As he was one of their own – ‘Michael Angelo Titmarsh’ – Punch took it on and published it in 20 serial parts printed by Bradbury & Evans, commencing in January 1847, at which point only three instalments had been written. This immediately followed the Book of Snobs, which ran in Punch from February 1846 to February 1847. Thackeray received a fee of £60 a number. Like Dickens’ serials from Chapman & Hall, each issue took the form of a pamphlet with a steel engraving (by Thackeray) on the cover wrapping three or four chapters, a couple of woodcut illustrations (also by the author) and some ads, price 1s. Dickens’ serials always bore a teal cover so pedestrians could spot his latest on the newsstand, and Bradbury & Evans did the same for Thackeray, selecting a vivid canary yellow that thereafter became his signature colour. When the serial concluded in July the following year, Bradbury & Evans published it in a single bound volume, now subtitled ‘A Novel without a Hero’. Critics in the main hailed Vanity Fair a work of genius and its author the equal of Dickens. ‘Currer Bell’ (as yet unidentified as Charlotte Brontë) effusively dedicated the second edition of Jane Eyre to Thackeray:

Why have I alluded to this man? I have alluded to him, Reader, because I think I see in him an intellect profounder and more unique than his contemporaries have yet recognised; because I regard him as the first social regenerator of the day—as the very master of that working corps who would restore to rectitude the warped system of things; because I think no commentator on his writings has yet found the comparison that suits him, the terms which rightly characterise his talent. They say he is like Fielding: they talk of his wit, humour, and comic powers. He resembles Fielding as an eagle does a vulture: Fielding could stoop on carrion, but Thackeray never does. His wit is bright, his humour attractive, but both bear the same relation to his serious genius that the mere lambent sheet-lightning playing under the edge of the summer cloud does to the electric death-spark hid in its womb. Finally, I have alluded to Mr. Thackeray, because to him—if he will accept the tribute of a total stranger—I have dedicated this second edition of ‘JANE EYRE.’

Thackeray made two grand in royalties alone that first year. Once more, he was a gentleman of means, but better still, he had finally achieved the literary recognition he had craved since the 1830s. He remained ‘at the top of the tree’, as he put it, for the rest of his life.

Like its author, Vanity Fair is unique within the English Victorian literary canon. In fact, to find anything like a correlative at all we must go to Tolstoy’s similarly epic War and Peace, serialised between 1865–1867 and more than a little inspired by Thackeray. (Aged 30 in 1853, Tolstoy had written that ‘There is one fact I must remind myself of as often as possible: at thirty, Thackeray was just preparing to write his first book.’ This wasn’t true, but you can see where he’s going here.) Both novels share several notional similarities. They are both set during the Napoleonic Wars, and Tolstoy’s protagonist Pyotr ‘Pierre’ Kirillovich Bezukhov is, like Thackeray’s Major William Dobbin, large-bodied, ungainly, and socially awkward but possessed of a heart of gold. In the Classical sense of rising and falling action, Waterloo represents Vanity Fair’s climax as the Battle of Borodino (1812) does War and Peace. Similarly, significant plot points at both battles also set up each novel’s romantic resolution, although Tolstoy’s is somewhat more upbeat than Thackeray’s. And just as Amelia Sedley’s family is ruined by her father’s financial mismanagement in Vanity Fair, so is that of Tolstoy’s heroine, Natasha Rostova. And on a textual level, there are scenes in War and Peace that are not a million miles from some of Thackeray’s. Most importantly, Thackeray’s project, like Tolstoy’s, was one of Realism not Romanticism. In fact, there is a case to be made that Vanity Fair is the first truly English Realist novel, heralding the literary prose form that would dominate the latter part of the 19th century across Europe until its absolute representational certainty died on the battlefields of the First World War.

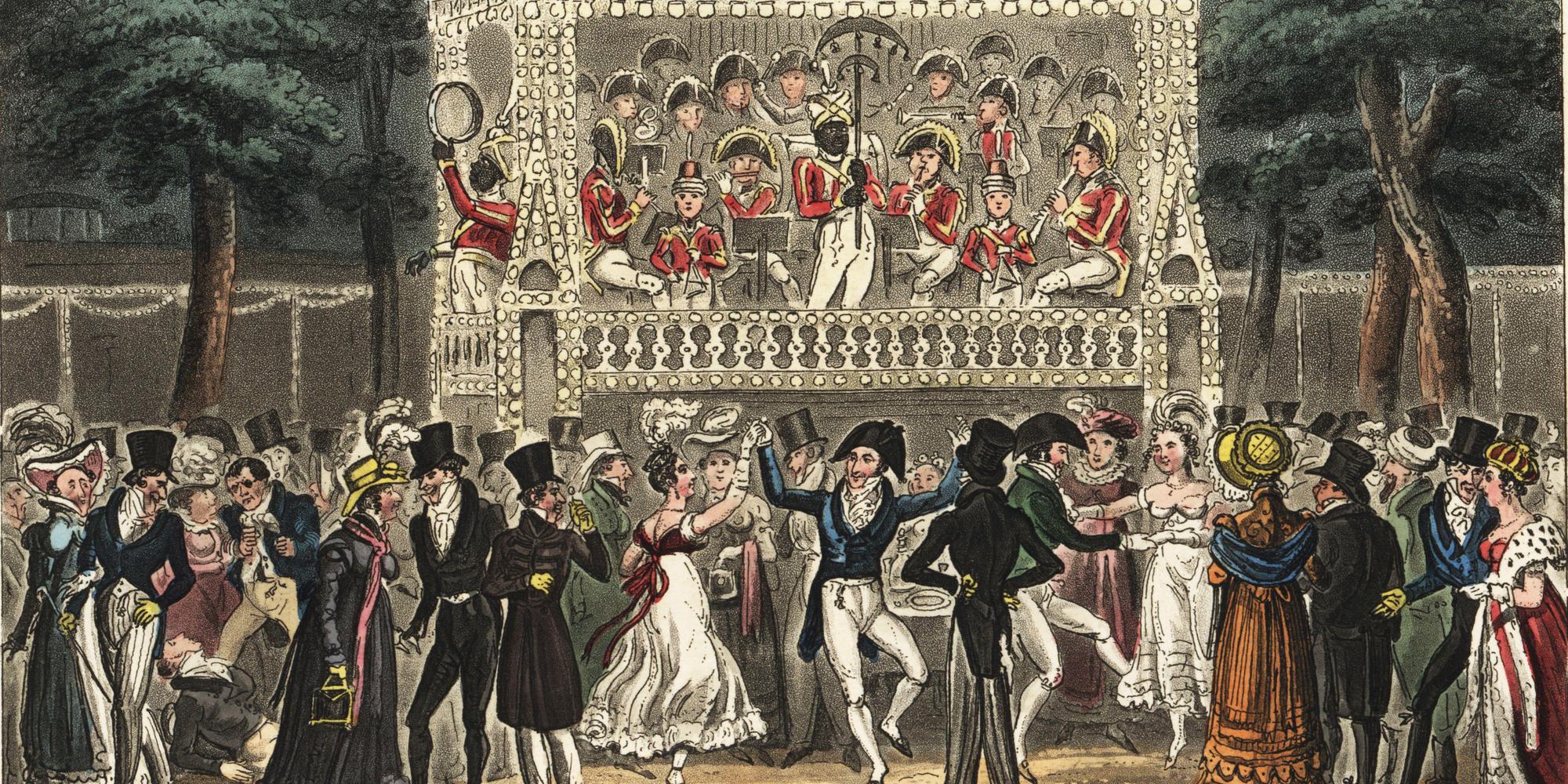

When reading Vanity Fair, as one reads a novel by Dickens, it is best to remember that these things began as serials, sometimes with story arcs planned well in advance, sometimes with instalments written on the fly to meet the deadline. There is thus a touch of the soap opera about Vanity Fair when it comes to plotting, with cliff-hanging chapter endings and startling reversals of fortune, all of which make for fun reading and go a long way towards explaining the novel’s continuing popularity as a subject of costume drama. (There are seven movies to date, including a racy pre-code version starring Myrna Loy as Becky Sharp – ‘Children not admitted!’ screamed the poster; four radio versions, six television dramas, the most recent by ITV and Amazon in 2018, and four plays, not counting all the Victorian theatrical knock-offs.) The story traces the interweaving lives of two socially juxtaposed female friends during the years leading up to Waterloo and its aftermath, beginning when the two girls graduate from Miss Pinkerton’s Academy for Young Ladies. The naïvely bourgeois Amelia Sedley is beloved by all, with a ‘smiling, tender, gentle, generous heart’, and leaves school demurely weeping. Her companion, the penniless and bohemian Becky Sharp, orphaned child of an artist and a French dancer, departs hurling the proffered leaving gift of Johnson’s Dictionary out of the window of the coach, symbolically cutting the mooring line with the values of social cohesion, patriarchal authority, and respect for tradition enshrined in that mighty volume. Amelia is the daughter of a successful stockbroker and is engaged to her childhood sweetheart, the soldier George Osbourne, the handsome but vain son of a wealthy merchant. Becky, meanwhile, who first stays with Amelia at the Sedley home in Russell Square, has the ‘dismal precocity of poverty’. She is highly intelligent, resourceful, and ambitious, with apparently no moral compass whatsoever, and sets her sights on trapping Amelia’s pompous and useless brother into marriage, thus achieving financial security and safe social status. Having no family to negotiate an advantageous marriage, Becky, as her author concedes, has no choice but to make the running herself. Although her ‘first move showed considerable skill’, Jos Sedley, the ‘Collector of Boggley Wollah’ (a bleak East India Company outpost), takes himself out of the picture after disgracing himself at Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. Becky goes to ‘Queen’s Crawley’ in Hampshire to become a governess to the children of the grotesque and semi-literate miser and MP, Sir Pitt Crawley. Things do not go as planned, naturally. The novel unfolds as Becky continues to attempt to advance her own interests while Amelia waits to marry the posing and profligate snob, George (who she idolises), while his best friend, Dobbin, looks on longingly from the side-lines. Napoleon escapes from Elba, and the friends, lovers and brothers all end up in Brussels as history drags them towards the inevitable carnage of Waterloo, after which nothing will ever be the same for any of them again… (And that’s only the first half of the novel.)

Not that Vanity Fair is that simple. You don’t acquire epithets like ‘the greatest novel in the English language’ with simple plotlines. Thackeray did not do ‘simple’; he despised it, as can be seen by his relentless critical attacks on Newgate novels in the late-1830s and his admiration of Henry Fielding. I just don’t want to spoil the story, because if you don’t know it yet then you’re in for a treat. (And don’t trust that Reece Witherspoon movie either; they changed the ending.) For a start, Vanity Fair is extremely funny, darkly comic in fact, in its insightful portrayal of the hidden drives and motives of ordinary humanity. Unlike Tolstoy, who was an aristocrat writing about aristocrats, and Dickens, who tended to see more virtue in people the further down the social ladder they sat, in Vanity Fair, no one is innocent. This is perhaps where it converges with The Book of Snobs and Thackeray’s earlier, more overtly satiric novels Catherine (1840) and The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1844), in which hypocrisy, duplicity, self-interest and pretension across classes are savagely deconstructed, for example:

Miss Briggs was not formally dismissed, but her place as a companion was a sinecure and a derision; and her company was the fat spaniel in the drawing-room, or occasionally the discontented Firkin in the housekeeper’s closet. Nor though the old lady would by no means hear of Rebecca’s departure, was the latter regularly installed in office in Park Lane. Like many wealthy people, it was Miss Crawley’s habit to accept as much service as she could get from her inferiors; and good-naturedly to take leave of them when she no longer found them useful. Gratitude among certain rich folks is scarcely natural or to be thought of. They take needy people’s services as their due. Nor have you, O poor parasite and humble hanger-on, much reason to complain! Your friendship for Dives is about as sincere as the return which it usually gets. It is money you love, and not the man; and were Croesus and his footman to change places you know, you poor rogue, who would have the benefit of your allegiance.

(Miss Crawley is Sir Pitt’s rich libertine half-sister. He and his bitter, debt-ridden younger brother Reverend Bute Crawley detest her, as they do each other, but suck up to her for the sake of the inheritance.) And for all this desire and scheming, the final irony of the novel is that when what is pursued is gained, it’s invariably not worth having: ‘Ah! Vanitas Vanitatum! which of us is happy in this world? Which of us has his desire? or, having it, is satisfied?’ In the richness of the prose, the wit, and the eye for detail, there is also an unerring psychological insight, a carrier wave embedded in every line. Hence the ‘Novel Without a Hero’. There are none; we are all as bad as each other. And this is the point of ‘Vanity Fair’.

Thackeray’s title is, of course, inspired. He was right to dance around the bedroom when it hit him. (Who wouldn’t?) ‘Vanity’ is a town which hosts a never-ending fair en route from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City in John Bunyan’s dissenting Christian allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678):

Almost five thousand years ago, there were pilgrims walking to the Celestial City, as these two honest persons are; and Beelzebub, Apollyon, and Legion, with their companions, perceiving by the path that the pilgrims made that their way to the city lay through this town of Vanity, they contrived here to set up a fair; a fair wherein should be sold all sorts of vanity, and that it should last all the year long. Therefore at this fair are all such things sold as houses, lands, trades, places, honours, preferments, titles, countries, kingdoms, lusts, pleasures, and delights of all sorts, as wives, husbands, children, masters, servants, lives, blood, bodies, souls, silver, gold, pearls, precious stones, and what not.

And, moreover, at this fair there are at all times to be seen jugglings, cheats, games, plays, fools, apes, knaves, and rogues, and that of every kind.

Any human attachment, Bunyan is saying, tempts us away from God. From its first appearance in print, ‘Vanity Fair’ quickly became synonymous with the world of men in general, which is how Thackeray is largely using it. (He was no Calvinist, and although a Church of England man, his correspondence suggests that he ended his life an atheist.) By Thackeray’s day, the meaning had also shifted to a playground for the indolent and undeserving rich, who certainly attract much of his ire in the novel. He uses it as both a controlling metaphor and a physical space, frequently applying it to Society gatherings in the novel and the real world from which he comments as author:

But my kind reader will please to remember that this history has ‘Vanity Fair’ for a title, and that Vanity Fair is a very vain, wicked, foolish place, full of all sorts of humbugs and falsenesses and pretensions. And while the moralist, who is holding forth on the cover (an accurate portrait of your humble servant), professes to wear neither gown nor bands, but only the very same long-eared livery in which his congregation is arrayed: yet, look you, one is bound to speak the truth as far as one knows it, whether one mounts a cap and bells or a shovel hat; and a deal of disagreeable matter must come out in the course of such an undertaking.

But although the moral of the story, at least one of them, is a warning to young readers to ‘learn to love and pray’, Thackeray’s morality feels more secular than conventionally Christian. And when, we are told, ‘the old man [Sedley Snr.] was about to go seek for his wife in the dark land whither she had preceded him,’ Thackeray’s conception of the afterlife sounds more like Hades than Heaven.

The almost carnivalesque device is further enlivened by a frame, in which the story is presented as a fairground puppet show:

As the manager of the Performance sits before the curtain on the boards and looks into the Fair, a feeling of profound melancholy comes over him in his survey of the bustling place. There is a great quantity of eating and drinking, making love and jilting, laughing and the contrary, smoking, cheating, fighting, dancing and fiddling; there are bullies pushing about, bucks ogling the women, knaves picking pockets, policemen on the look-out, quacks (OTHER quacks, plague take them!) bawling in front of their booths, and yokels looking up at the tinselled dancers and poor old rouged tumblers, while the light-fingered folk are operating upon their pockets behind. Yes, this is VANITY FAIR; not a moral place certainly; nor a merry one, though very noisy…

He is proud to think that his Puppets have given satisfaction to the very best company in this empire. The famous little Becky Puppet has been pronounced to be uncommonly flexible in the joints, and lively on the wire; the Amelia Doll, though it has had a smaller circle of admirers, has yet been carved and dressed with the greatest care by the artist; the Dobbin Figure, though apparently clumsy, yet dances in a very amusing and natural manner…

‘And with this,’ the whimsical Preface concludes, ‘and a profound bow to his patrons, the Manager retires, and the curtain rises.’

So, how is all this Realist, I hear you ask? This is hardly Middlemarch, is it; it’s more of a satire, surely? This is a good question. Think of it, perhaps, as a transitioning Realism, a paradigm-shifting with a clutch. And all the while, Thackeray is defining his narrative against the Romantic and popular novel:

We might have treated this subject in a genteel, or in romantic, or in a facetious manner. Suppose we had laid the scene in Grosvenor Square, with the very same adventures—would not some people have listened? Suppose we had shown how Lord Joseph Sedley fell in love, and the Marquis of Osborne became attached to Lady Amelia, with the full consent of the Duke, her noble father: or instead of the supremely genteel, suppose we had resorted to the entirely low, and described what was going on in Mr. Sedley’s kitchen … such incidents might be made to provoke much delightful laughter, and be supposed to represent scenes of ‘life.’ Or if, on the contrary, we had taken a fancy for the terrible, and made the lover of the new femme de Chambre a professional burglar, who bursts into the house with his band … and carries off Amelia in her night-dress, not to be let loose again till the third volume, we should easily have constructed a tale of thrilling interest, through the fiery chapters of which the reader should hurry, panting. But my readers must hope for no such romance, only a homely story, and must be content with a chapter about Vauxhall, which is so short that it scarce deserves to be called a chapter at all. And yet it is a chapter, and a very important one too. Are not there little chapters in everybody’s life, that seems to be nothing, and yet affect all the rest of history?

The literary critic J.I.M. Stewart calls this Thackeray’s ‘special quality’ and makes a virtue of the idiosyncrasy: ‘It is because his creation is always distinguishably and avowedly his creation that he can stroll through it as he does, and comment as he pleases.’ Thackeray’s Realism is certainly distinctive. As noted above, it is deeply psychological, with raw honesty and moral complexity not usually expressed in the Victorian novel. When, for instance, a father hears of the death of his estranged son, his reaction is more narcissistic than bereaved:

But now there was no help or cure, or chance of reconcilement: above all, there were no humble words to soothe vanity outraged and furious or bring to its natural flow the poisoned, angry blood. And it is hard to say which pang it was that tore the proud father’s heart most keenly—that his son should have gone out of the reach of his forgiveness, or that the apology which his own pride expected should have escaped him.

Compare this to a death scene in Dickens. He would have made it sentimental, reflective, and religious, but Thackeray never does this. Dickens favoured kindness and Christian charity, Thackeray, the unalloyed truth. And such psychological truth is rarely kind if we open ourselves up to the reality of the human experience. It is at best contingent, expedient, and often mildly disturbing; mostly, like the world, it’s just cruel, hence the stories we tell ourselves to prove that it isn’t. As Nietzsche wrote in Beyond Good and Evil: ‘“I did that,” says my memory. “I could not have done that,” says my pride, and remains inexorable. Eventually—the memory yields.’ This is the ‘Greek fire’ that Charlotte Brontë admired so much in Thackeray’s writing, and he turns it on everyone, the jokes offsetting a key-bending insight into the dark heart of the Victorian consciousness.

This was nothing new in Thackeray’s writing. He loved to strip away the veneer of things, to show the artifice behind the act, in a way that reduced even the most practical or artistic choice to a lie. This can be seen in his attack on Dickens’ Oliver Twist in Fraser’s Magazine:

Boz, who knows life well, knows that his Miss Nancy is the most unreal fantastical personage possible; no more like a thief’s mistress than one of Gessner’s shepherdesses resembles a real country wench … He dare not tell the truth, and not being able to paint the whole portrait, he has no right to present one or two favourable points as characterising the whole, and therefore had better leave the picture alone altogether.

His first published book, Flore et Zéphyr (1836), was a series of lithograph illustrations depicting the seedy backstage reality of ballet. This was an artform, incidentally, that he loved, just as he loved the dancer Marie Taglioni, Dickens, and the Newgate novelist W.H. Ainsworth, whose writing he never tired of shredding in public. Thackeray was a man who would not compromise, ever, even if it cost him a lover or a friend, and if there was one thing he really despised, it was sacred cows. ‘Nothing,’ he liked to say, ‘is so overrated as the Fine Arts.’

And while turning inward with such precision, the other aspect of Thackeray’s realism is his sheer range. As G.K. Chesterton wrote of Vanity Fair, ‘the chief character is the world’. Professor John Carey calls this Thackeray’s ‘panoramic realism’ which, he explains, ‘surrounds the major figures with a seemingly endless cast of minor characters, to create an impression of life proliferating in all directions.’ This, says Carey, is what gives the voice of the novel its ‘air of knowingness’. Remember, in conventional Realist narrative, the author is God: omnipotent, omniscient, immutable… objective, never subjective; an authority figure representing the stability of society and empire. And Thackeray’s Realism allows for this as a universal narrative perspective, but at the same time he plays with it by being much more all-knowing than might be comfortable for his subjects. He’s a god with a dark sense of humour too, the puppet master of a cheap, gaudy show. There is also a sense of creative evolution here. Although thematically similar to his earlier writing, Vanity Fair is a much more sophisticated narrative. Thackeray’s previous work had always been parodic, his characters merely spheres of action designed to express his ideas, often with quite generic names. In Vanity Fair, they came to life for him, they spoke not through him but to him, in that wonderful alchemy of character creation that all writers know. He thus visited the Hôtel la Terrasse in Brussels, where his protagonists once stayed, writing to Jane Brookfield that: ‘How curious it is! I believe perfectly in all those people and feel quite an interest in the inn in which they lived.’

In is in this statement, perhaps, that we begin to realise that Vanity Fair is not simply the work of a cynic. Despite all the biting satire and apparent Manichaeism, it would seem that Thackeray’s more standard snark went into The Book of Snobs, allowing Vanity Fair to become something else. There is certainly continuity with Thackeray’s earlier writing, the brilliant but arrogant iconoclasm, but is it really ‘A Novel Without a Hero’?

Modern scriptwriters like Andrew Davis are pretty sure the novel’s hero is Becky Sharp. The costume dramas certainly all revolve around her, and they celebrate her sexuality, her ingenuity, and her industry in a rich man’s world. When Davis adapted Vanity Fair for the BBC in 1998, the Radio Times put Becky (played by the gorgeous Natasha Little) on the front cover with the tagline ‘Girl Power’, subtitled: ‘If you don’t know a woman like Becky Sharp you’ll want to’, which probably isn’t alluding to learning more about Thackeray’s famous novel. And this is a fair point. Becky is the most interesting character in the novel, as well as the most intelligent, and she’s also a long way from the stereotypical femme fatale that would later arise in Sensation Fiction. By contemporary standards, she’s a strong female lead: sexy, funny, and independent. But to impose this reading on Thackeray would be inaccurate. Thackeray the man understands Becky’s motivations, but the moralist does not condone them, leading to some quite wild oscillations in tone when she is described or depicted (the original text was also full of Thackeray’s illustrations, often showing Becky in symbolic roles, such as Napoleon and Clytemnestra). Like Amelia, Becky is multifaceted and ultimately a deliberately ambivalent character. Amelia starts out as apparently squeaky clean, with an emphasis on the squeaky. She’s a nice, pretty if slightly shallow young Victorian gentlewoman – a stereotype in life and literature at that point – who then becomes more emotionally complex as her life unfolds. Similarly, there’s more to Becky Sharp than the angry gold digger. You’ll need to read the book to find out what, mind, but let’s just say Thackeray never really commits one way or the other, leading to one of the great mysteries of Victorian fiction.

If there is a hero, and therefore some hope in Vanity Fair, then it is William Dobbin, a late addition to the project which necessitated a substantial redrafting of the opening chapters before Vanity Fair began its serial run. Dobbin is the awkward son of a London merchant and best friend to George Osbourne, of whom he has been fiercely protective and indulgent since they were at school together. Their relationship is largely unchanged now that they both serve in the same regiment. Although sometimes a figure of fun, though not so much as the Collector of Boggley Wollah, the clumsy Dobbin is the only character in the novel who is truly decent. He’s kind, honest, generous, and modest; and while he often supports George and Amelia, his good works are so subtle they frequently aren’t even aware that he’s doing anything. He gains no credit for his actions, and as a man in love with another man’s wife, any help he gives the marriage can only hurt his chances of ultimately gaining his heart’s desire. The torch he carries is as much the through-line of the novel as Becky’s ruthless ambition. If she is the brain of the novel, then he is the heart.

It is the last-minute inclusion of Dobbin in the project that saves Vanity Fair from the relentless negativity and disdain of all Thackeray’s earlier fiction and journalism. He is also, in part, an avatar of the author, a human counterpoint to the narrative deity overseeing the broader action. This is because, while Thackeray was planning and writing Vanity Fair, he too was in the grip of hopeless and unrequited love.

Thackeray married an Irish girl, Isabella Gethin Shawe (1816–1894), in 1836. Isabella was the daughter of Isabella Creagh Shawe and Colonel Matthew Shawe, with whom he became captivated, he later told his children, after hearing her sing at his grandmother’s home when he was 25. Henry Reeve, the editor of the Edinburgh Review, describes Isabella in his diary as ‘a nice, simple, girlish girl’ and Amelia Sedley was later based partly on her. The marriage appears to have been a happy one until tragedy struck after the birth of their third child, Harriet in 1840. Isabella became gravely and inexplicably ill after the birth, with what we would nowadays recognise as postnatal depression. Doctors recommended health spas, and it was assumed that whatever was going on was a result of the trauma of childbirth and that it would pass. Thackeray initially struggled to work around his wife’s illness, eventually putting everything on hold to take her to her family in Ireland. On the crossing, she attempted suicide by jumping from the ship. Isabella spent the next two years in and out of professional care while her husband desperately sought out possible cures, until she eventually sank into a permanent state of psychosis from which she never recovered. Thackeray placed his wife with a full-time carer in 1845 and became a de facto widower, raising his girls and never remarrying. (Isabella outlived him by 30 years, dying in 1894.) And this appears to have been a genuine case of incapacity through incurable mental illness, not one of those sinister Victorian committals whereby husbands divested themselves of feisty, independent and intelligent wives by incarcerating them in asylums, as Bulwer-Lytton had done to his wife, Rosina.

Lonely, frustrated and shellshocked, Thackeray had met and fallen for the literary hostess and writer Jane Octavia Brookfield (1821–1896) in 1842, the wife of a friend from Cambridge, the Reverend William Henry Brookfield. Jane, then 21, was ten years Thackeray’s junior. From their surviving letters, it is difficult not to conclude that she strung him along much as Amelia does Dobbin in Vanity Fair, accepting his devotion but quickly retreating into matrimonial loyalty if he ever tried to take things further; blowing hot and cold until Thackeray was, by his own confession, ‘half-mad with love’. To make matters worse, Brookfield (like George Osbourne) was an indifferent and neglectful husband, but he was proud enough to eventually forbid the two from ever communicating again in 1851. ‘I wish I had never loved her,’ wrote Thackeray. ‘I have been played with by a woman, and flung over at a beck from the lord and master.’ When Dobbin finally cracks and delivers his lecture to Amelia towards the end of the novel, it is clearly Thackeray addressing Jane:

‘No, you are not worthy of the love which I have devoted to you. I knew all along that the prize I had set my life on was not worth the winning; that I was a fool, with fond fancies, too, bartering away my all of truth and ardour against your little feeble remnant of love. I will bargain no more: I withdraw … Let it end. We are both weary of it.’

(Not that this is the end, of course. As I said, you must find out for yourselves.) In short, Thackeray reminds his audience, ‘This history has been written to very little purpose if the reader has not perceived that the Major was a spooney.’ Dobbin, of course, shares Thackeray’s Christian name, as well as several of his physical characteristics. Amelia may have started out like the innocent and beautiful Isabella, but by the end of the novel, she was undoubtedly Jane.

At its heart, then, Vanity Fair is a love story with a significant autobiographical element that therefore makes it very different from anything Thackeray had written before: a vast and satiric critique of a society obsessed with wealth and rank, and of the essentially avaricious nature of humanity. It is also Thackeray’s most concerted and refined challenge to the long Classical/Renaissance/Romantic tradition of the ‘heroic’ hero, just as Milton had rejected the same archetype in Paradise Regained, replacing it with the figure of Christ. In Major Dobbin, the ordinary and awkward, the decent, the flawed, and the selfless become the true heroes of life and literature, rather than brooding, superhuman and sexually magnetic warriors who are always brave, handsome, and funny. And it is precisely because Dobbin is so complex and realistic that we can accept him as the unheroic hero. Imagine how insufferable he would be if more two-dimensionally virtuous. This, ultimately, is the genius of Thackeray’s Realism in Vanity Fair, a form of narrative that was to have a seismic influence on the development of the English novel.

Finally, Vanity Fair lies at the heart of an unprecedented renaissance in English literature. When it appeared in book form in 1848, the year of the European revolution, it joined Dickens’ Dombey and Son (recently concluded in serial form), while following Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Disraeli’s Tancred, which had all been published the year before. 1848 also saw the publication of Gaskell’s Mary Barton, Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Charles Kingsley’s first novel, Yeast. It is difficult to identify a higher point in the history of English fiction. There had been great novelists before, but this was an entire generation of great novelists.

Stephen Carver

Image: Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens 1820. Hand-coloured copperplate engraving by Isaac Robert Cruikshank and George Cruikshank from Pierce Egan’s Life in London, Sherwood, Jones, London, 1823.

Credit: Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article