Sally Minogue looks at Emily

Emily, a film loosely based on Emily Brontë’s life, has hit the screens. Sally Minogue finds herself at odds with the rave reviews.

As soon as I had seen the film Emily, I knew what the first sentence of this blog was going to be: ‘Emily is pure codswallop’. But me no buts. But … since then, I have read and listened to the reviews, and across the board they are a minimum four-star – respectful, admiring, sometimes even passionate in their praise. The Guardian times two, including one by respected critic Peter Bradshaw, The Independent, The Telegraph, The Irish Times, The Sunday Times (five stars the latter), all rave about it. Mark Kermode, who knows his stuff, couldn’t contain his excitement on Kermode and Mayo’s Take on YouTube: ‘the blood courses through the veins of the film!’ Accompanied by a lot of waving of hands. The two reviews on BBC Radio 4’s Front Row (Oct 13) and Radio 3’s Free Thinking (Oct 13) were lavish in their praise. Only the Evening Standard raised some of my own questions (which I’ll elaborate later). In Front Row, Samantha Ellis, biographer of Anne Brontë, described the film as ‘exhilarating’ and dismissed the many inaccuracies in favour of its emotional truth. And when Tom Sutcliffe asked the more generalist reviewer, archaeologist Mike Pitts, how he felt when he left the cinema, he said ‘I was in tears’. I was waiting for the Wildean completion – tears of laughter. But no; they were tears of genuine emotion. Even the sharply attuned Sutcliffe, who did have some reservations, compared it to a Hardy novel.

Emily Brontë c.1834

So where am I going wrong? The obvious answer might be that I am one of those viewers who looks for every inaccuracy and anachronism in an imaginative rendering of the past, and that I couldn’t get beyond the many ways the film strayed from the recorded facts. There is some truth in this, because there were elements of such huge improbability in the way Emily Brontë’s life was depicted that I found it hard to suspend my disbelief. But I am not of the school that thinks factual inaccuracy trumps imaginative truth. I loved the film 1917, panned by so many historians of the First World War for perceived improbability and for getting the factual details wrong, because I thought it captured the lived consciousness of a particular man caught up in that war. And moving closer to home, while I had reservations in my blog about Sally Wainwright’s 2016 BBC One film about the Brontës, To Walk Invisible, that was only because it foregrounded Branwell’s eventually boring excesses over the productive writing lives of his three siblings. What Wainwright celebrated in the end, and what I celebrated in her film, was that the three Brontë women produced lasting work, while their brother didn’t.

Here I think we come to the nub of the difficulty, not just in representing any of the Brontës, but in representing any writer on film. How do you show the writing? The writer and director of Emily, Frances O’Connor, opts to show the novel’s imaginative springs in place of the writing. But this is where I really take issue with the film. It begins by asking the question, via Charlotte speaking to Emily on her deathbed, ‘How did you write Wuthering Heights?’ This is presented as an aggressive question, i.e. ‘How on earth…?’ But Charlotte did have some understanding of where Emily’s novel came from – ‘the wild moors of the North of England’. It was only those (metropolitan) readers who were ‘unacquainted with the locality where the scenes of the story are laid’ to whom the novel ‘must appear a rude and strange production’. These remarks are from her Preface to the posthumous re-issue of Wuthering Heights (1850), where, still writing at that time as Currer Bell, she continues:

It is rustic all through. It is moorish, and wild, and knotty as the root of the heath. Nor was it natural that it should be otherwise; the author herself being a native and nursling of the moors. … Wuthering Heights was hewn in a wild workshop, with simple tools, out of homely materials. The statuary found a granite block on a solitary moor … He wrought with a rude chisel, and from no model but the vision of his meditations. With time and labour, the crag took human shape; and there it stands, colossal, dark, and frowning, half statue, half rock …

We can take Charlotte’s male pronoun here to be preserving the Ellis Bell pseudonym. But other than this distancing, Charlotte’s description of the novel is couched in remarkably similar language to that of Cathy Earnshaw describing to Nelly her feelings for Heathcliff:

If all else perished and he [Heathcliff] remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger … My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath – a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff –

I find little in Charlotte’s Preface to justify the film’s view of her as uncomprehending of and shocked by Emily’s fictional vision (a view endorsed, inaccurately, by Emma Butcher in BBC Radio Three’s Free Thinking programme). In the Biographical Notice that Charlotte wrote about her two sisters (still named under the pseudonyms of Ellis and Acton Bell) around the same time as the 1850 Preface, she is far more judgemental about Anne’s novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall: ‘The choice of subject was an entire mistake.’

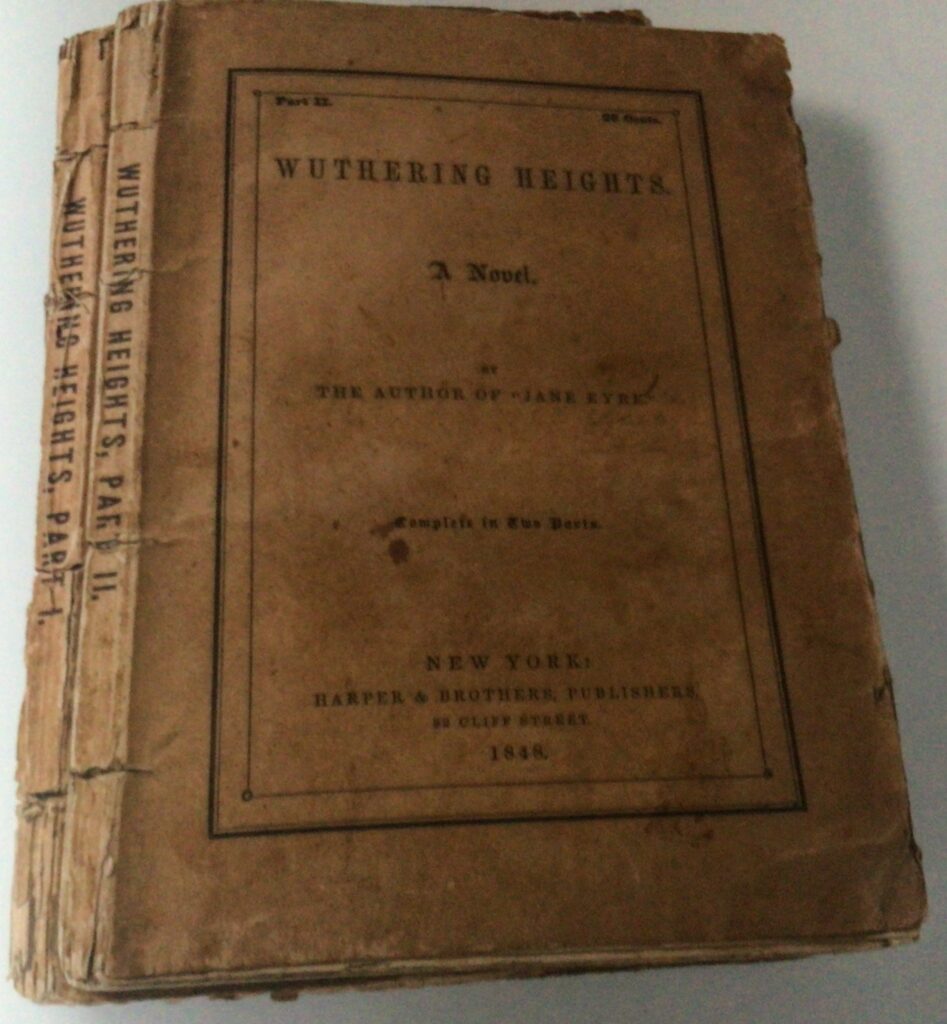

First American edition of ‘Wuthering Heights’, mistakenly attributing it to ‘the author of ‘Jane Eyre’’

True, Charlotte’s characterisation of Wuthering Heights is entirely metaphorical, but she is paying obeisance to the unknowable power and wellsprings of imagination itself. Against this admittedly inchoate understanding, the film gives us a baldly literal answer to the original question, ‘How?’. Obviously, for Frances O’Connor, Emily Brontë couldn’t have produced a fiction such as Wuthering Heights unless she had shared brother Branwell’s opium habit and had a no-holds-barred affair in a ruined cottage in the middle of the moors with the live-in curate. Oh, and I forgot – sometimes they had a romp in said curate’s bed (in a lovely oak-panelled room, presumably therefore well sound-proofed).

I honestly would like to think, for her own sake, that Emily had had a sexual relationship before she died, and even more I’d like to think she was truly loved in that passionate way – just as I’d like to think the same of John Keats. But in both cases, the probability is otherwise. For Emily in particular, the moral (not to mention the reproductive) strictures of the time on a woman would have made such an affair as that shown here between her and the curate William Weightman well-nigh impossible for both of them. And then there’s the issue of the private space available in which to conduct such an affair. It’s true that the moors were in one sense a place of freedom, and all the Brontë sisters wandered them as of right. Nonetheless, there’d have been plenty of eyes keeping track of their movements. An actual bed would have been out of the question. As for the opium, Branwell’s excesses in that direction, as with alcohol, are extensively documented, both by Charlotte and by her biographer Elizabeth Gaskell. They were never hidden in spite of the shame they carried with them, and Charlotte writes quite openly in a series of letters to her old friend Ellen Nussey, about Branwell’s decline after he is dismissed as the Robinsons’ tutor, in disgrace because of his affair with Mrs. Robinson (1845):

We have had sad work with Branwell. He thought of nothing but stunning or drowning his agony of mind. … We must all, I fear, prepare for a season of distress and disquietude.

(August, 1845) Things … not very bright as it regards Branwell, though his health, and consequently his temper, have been somewhat better this last day or two, because he is now forced to abstain.

(August 18th, 1845) My hopes ebb low indeed about Branwell. I sometimes fear he will never be fit for much.

Elizabeth Gaskell is rather more brisk about this period: ‘he began his career as an habitual drunkard to drown remorse.’ Writing of his drug and alcohol addiction, she is direct:

For the last three years of Branwell’s life, he took opium habitually, by way of stunning conscience; he drank, moreover, whenever he could get the opportunity. … He took opium, because it made him forget for a time more effectually than drink; and besides, it was more portable. (The Life of Charlotte Brontë, Wordsworth, pp. 205-6)

While it is true that similar excesses, sexual or addictive, from a woman in the family would have invoked far greater blame and perceived dishonour, if there had been any behaviour by Emily similar to that of Branwell, it surely would have been an overt cause of concern within the family in the same way. What emerges from Branwell’s story is the anxiety and vicarious disappointment the whole family have for him, even when they despair of his behaviour. Immediately after his death, Charlotte wrote to Ellen, ‘All his vices were and are nothing now. We remember only his woes.’ The desperate effects of his addictions would surely have terrified his siblings away from any similar indulgence, even if it had been available.

But now it is I who am being over-literal. The counter-argument is that this film, in the life it extrapolates for Emily Brontë, is itself an act of imagination, conjuring for us what her life might have been, could have been, maybe was (and this is O’Connor’s stated intention). It is itself a metaphorical act, much as Charlotte’s description of the powers underlying Wuthering Heights is. The problem is that the visual narrative of the film, with its actual depictions of sex and its dwelling lovingly on the very long time it takes Weightman to undo Emily’s corset, is resolutely realist. Similarly, we are given close-ups of Emily’s dilated pupils as she rolls in the heather with Branwell, their having taken opium together. Nothing is left to our imagination.

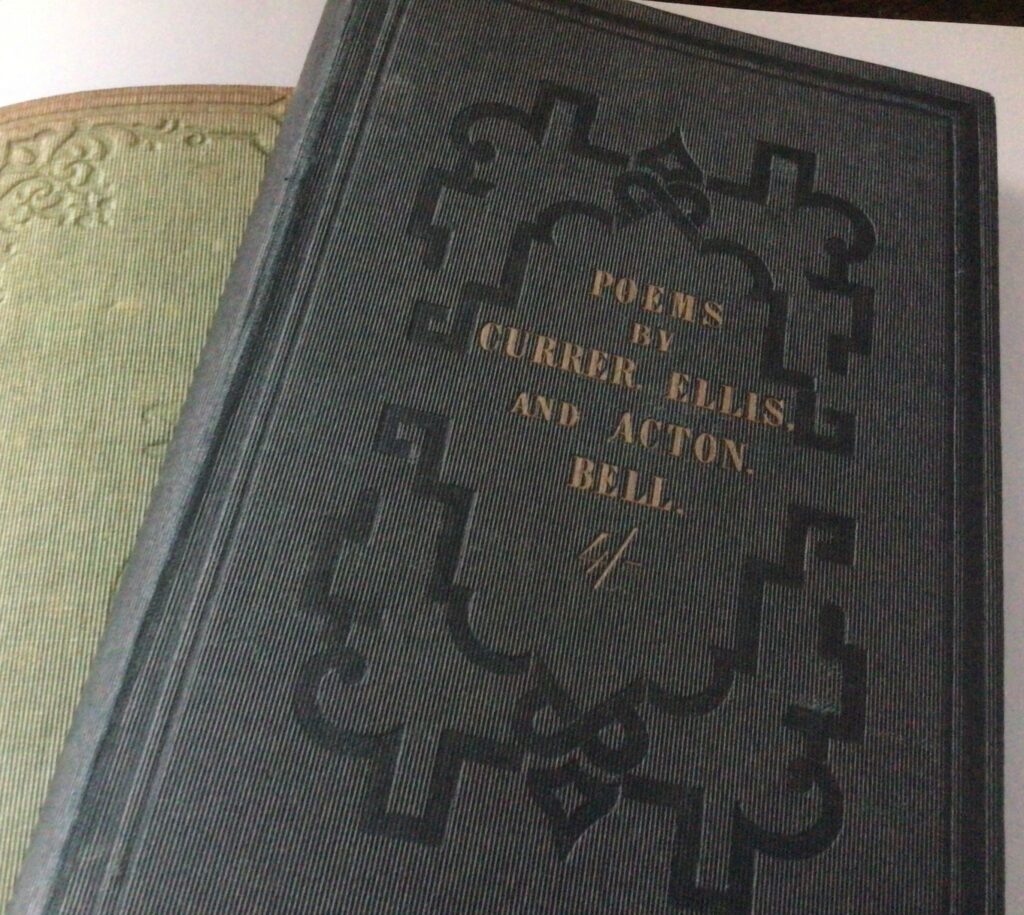

First edition of the three Brontë sisters’ Poems, 1846, under their pseudonyms.

At least Charlotte knew from her own writing experience that the imagination can range far beyond the lived experience. The Brontës’ juvenilia speaks clearly to this. Reference is made to that in the film, Anne shown as rejecting Emily’s desire still to inhabit their world of Gondal with its Byronic heroes. But Frances O’Connor has replicated Gondal with a similarly Byronic hero in William Weightman, surely more a product of a fevered imagination than any actual curate. Weightman the curate did exist. That’s about as much as can be said.

Charlotte took a pretty dim view of curates, one she draws on playfully at the start of her novel Shirley, at the same time issuing a mindful corrective to sensationalism:

Of late years an abundant shower of curates has fallen upon the north of England: they lie very thick on the hills; every parish has one or more of them; they are young enough to be very active, and ought to be doing a great deal of good. …

If you think, from this prelude, that anything like a romance is preparing for you, reader, you never were more mistaken. Do you anticipate sentiment, and poetry, and reverie? Do you expect passion, and stimulus, and melodrama? Calm your expectations …

If this sounds like the prim Charlotte depicted in the film, all buttoned up in jealousy of her sister, hair scraped back and spectacles firmly clamped on, remember Jane Eyre! What she writes here about romance is a direct response to expectations raised by her first-published highly successful novel. Jane Eyre was indeed also the first novel to be published by any of the three sisters. In the film (counterfactually) it is Emily’s novel that is published first. That inaccurate chronology doesn’t really matter as much as the complete misrepresentation of the centrality of the act of writing undertaken by all three sisters both before and during the time depicted in the film.

All of the Brontës, including Branwell, were writing from childhood, starting with the Glass Town fantasies. Charlotte’s own minuscule handmade book of poems, written aged 13, and woven tightly in tiny handwriting, recently made a record $1.25 million at auction and was donated by the buyer to the Haworth Parsonage Museum. Branwell and Charlotte later diverged to the creation of Angria, and Emily and Anne to that of Gondal. These were imagined worlds, well realised, peopled with dramatic characters, but they are juvenilia. A number of Emily’s poems emerge from the Gondal world, and are expressions from characters therein, though of course these characters may have been used by Emily as a projection of herself. Once they eventually left behind these melodramatic worlds, the four siblings carried on writing poems, and they were not without ambition. In December, 1836, Charlotte sent her poems to the then Poet Laureate Robert Southey, and in the following January, Branwell sent his to William Wordsworth. One can imagine the weariness with which these famous, seasoned poets received what were essentially adolescent literary offerings. Southey’s reply is famed: ‘Literature cannot be the business of a woman’s life, and it ought not to be.’ Charlotte wrote an ostensibly submissive reply, to which Southey to his credit replied kindly; but luckily she took no notice of his first advice.

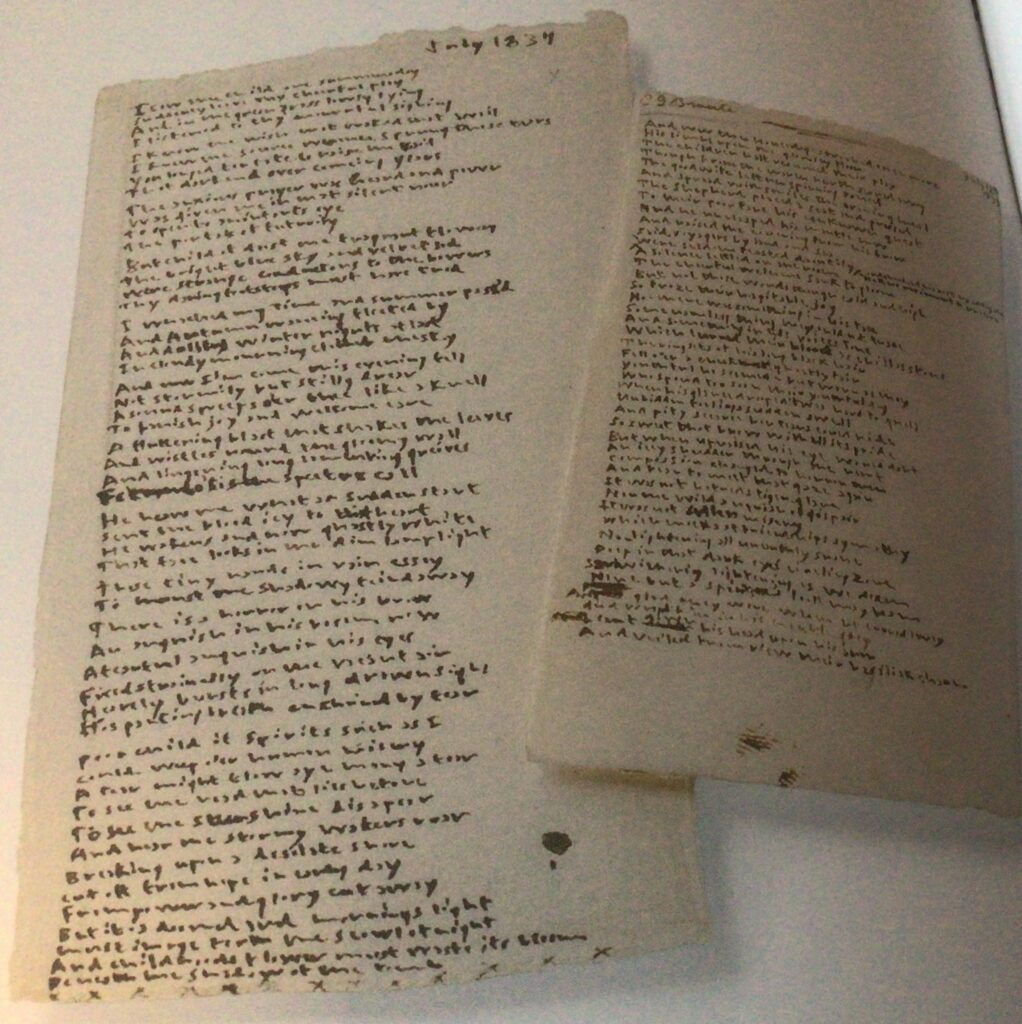

Manuscripts of two untitled poems by Emily Brontë

The next step in their writing life was occasioned by Charlotte’s having, in 1845, ‘accidentally lighted on a manuscript volume of verse in my sister Emily’s handwriting’:

I looked it over, and something more than surprise seized me – a deep conviction that these were not common effusions, nor at all like the poetry women generally write. I thought them condensed and terse, vigorous and genuine. To my ear they had also a peculiar music, wild, melancholy, and elevating. (Biographical Notice)

There couldn’t be a better characterisation of Emily’s poetry. The discovery prompted the publication of a collection of the poetry of all three sisters in 1846, and the assuming of their original pseudonyms, Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. The volume fell dead from the press; but the seed was sown.

The rest is history – a history turned topsy-turvy by this film, Emily receiving a package with a three-volume Wuthering Heights, published, absurdly, under her own name. In one way though this does some poetic justice (except to Anne!) since Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey were the first Brontë novels to be accepted by a publisher, Thomas Newby. His dilatoriness meant that Jane Eyre was published first, by Smith, Elder, in October 1847. The runaway success of Charlotte’s novel probably then hastened Newby’s publication of the joint Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey, in December 1847. Indeed initially, Emily’s novel suffered the annoying fate of being mistaken as apprentice work by the same author as Jane Eyre. Given all we know of Emily’s averseness to the public world, I don’t think ‘being first’ would have concerned her much, any more than she would have minded sharing her publication space with Anne. And she was almost certainly more comfortable publishing under a pseudonym than otherwise. The film is, however, right in one sense. Emily Brontë would have had the satisfaction of holding her own fictional vision in her own hands in the material form of a published book, Wuthering Heights, which would go out into the world – though even her prodigious mind would have fallen short of imagining a film called Emily. We await the film that shows her, or indeed any writer, drawing directly on their inner selves for their work, and struggling with the actual act of writing.

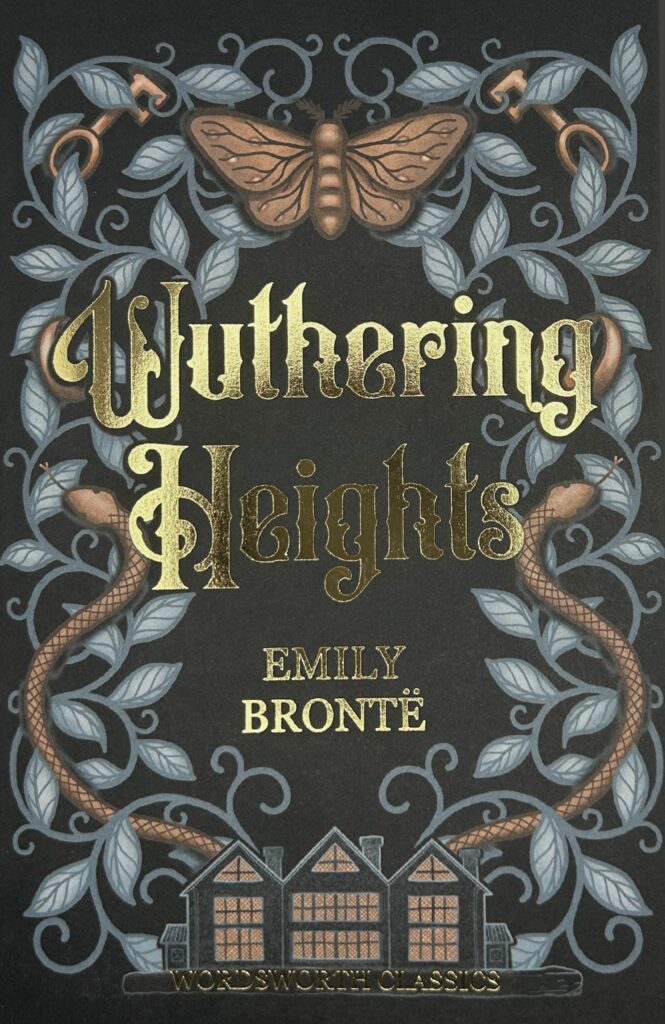

All of the Brontë novels are published by Wordsworth. Wuthering Heights is also published in both the Collectors’ Editions and in The Luxe Editions.

Frances O’Connor’s film Emily was released by Warner Brothers in the UK in October 2022. Emily Brontë is played by Emma Mackey in what, regardless of my criticisms of the film, is a truly remarkable performance. William Weightman is played by Oliver Jackson-Cohen, hamstrung by having to vie between correct curate and proto-Heathcliff; and Branwell (again, convincingly) is played by Fionn Whitehead. Charlotte is played by Amelia Gething – it’s not the actress’s fault, but presumably the result of writing and direction, that she is in my view quite misrepresented. The music, which carries rather too much of the emotional weight of the film, is by Abel Korzeniowski. The Yorkshire countryside plays itself – the one fully authentic thing in Emily.

The Brontë Society and the Brontë Parsonage Museum website can be found here: https://www.bronte.org.uk/

Main image: Emma Mackey in the 2022 film

Image (1) above: Emily Brontë: detail from the group portrait of the three sisters by their brother, Branwell c.1834 Credit: Ian Dagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

Image (2) above: This is the first American edition of Wuthering Heights, mistakenly attributing it to ‘the author of Jane Eyre’

Image (3) above: This is the first edition of the three Brontë sisters’ Poems, 1846, published under their pseudonyms.

Image (4) above: Manuscripts of two untitled poems by Emily Brontë, in her hand, from 1837 and 1839 respectively. These were not published until the early 20th century.

Images (2)-(4) photographed by Sally Minogue from The Brontes: A Family Writes exhibition catalogue by Christine Nelson for the Morgan Library and Museum, 2016

Books associated with this article

Wuthering Heights (Luxe Edition)

Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights (Collector’s Edition)

Emily Brontë