The Fall of the House of Usher

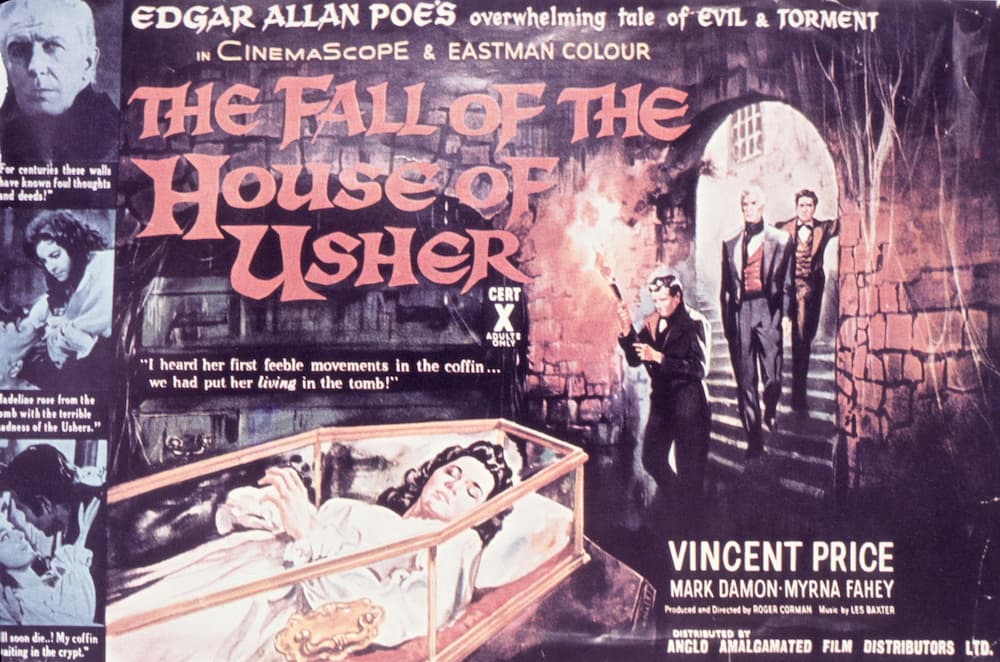

In the summer of 1960, American International Pictures released a little gothic number called The Fall of the House of Usher based on the strange and phantasmagoric short story of the same name by Edgar Allan Poe, first published in Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine in 1839. AIP was a low-budget, independent outfit that banged out cheap and cheerful genre films primarily aimed at the teenage drive-in audience, such as Hot Rod Girl, I Was a Teenage Werewolf, She Gods of Shark Reef, Motorcycle Gang, and Teenage Caveman. The Fall of the House of Usher was a more ambitious project, inspired by the success of Hammer Films in the UK, who had reinvigorated the tired gothic archetypes of the Universal Studies Karloff/Lugosi era as intense period dramas with more than a hint of sex and violence. The Fall of the House of Usher was written by Richard Matheson – a prolific pulp author and screenwriter of a similar stature to his contemporaries Ray Bradbury and Robert Bloch – and directed by AIP mainstay and ‘King of Cult’ Roger Corman. It starred the aging character actor Vincent Price, who was beginning to reinvent himself as a horror icon (much like failed Shakespearian actor Peter Cushing in Britain), after his success in Warner Brothers’ House of Wax (1953). Unlike AIP’s standard output, the film was shot in colour, with a decent if medium budget and a lush musical score by Les Baxter. After all these years it is still worth seeking out, just for the power of its gothic epiphany when Price’s Roderick Usher whispers in horror, ‘We have put her living in the tomb!’

Poster for the 1960 film, directed by Roger Corman

Much like Hammer’s Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula a couple of years before, The Fall of the House of Usher’s effect on the cinema-going public was electric. Unlike the novels of Mary Shelley, Bram Stoker, and Robert Louis Stevenson, Poe’s work had not been adapted and popularised during the previous highpoint of gothic cinema in the 1930s and 40s and was more associated with American high school English classes, a connection Variety made at the time. Jaded audiences now re-evaluated, discovering, or perhaps remembering the master of the macabre in American literature, doubly fresh for having none of the baggage of numerous Dracula and Frankenstein movies. The film established Price as a leading man and a star (while at the same time typecasting him forever) and was a critical and commercial triumph for Corman and AIP. Thus began their lucrative and influential five-year ‘Poe Cycle’ of films, following House of Usher with The Pit and the Pendulum, The Premature Burial, Tales of Terror, The Raven, The Terror, The Haunted Palace, The Masque of the Red Death, and The Tomb of Ligeia. Stephen King later disclosed in On Writing that he learnt his trade as a schoolkid copying Matheson’s Poe screenplays.

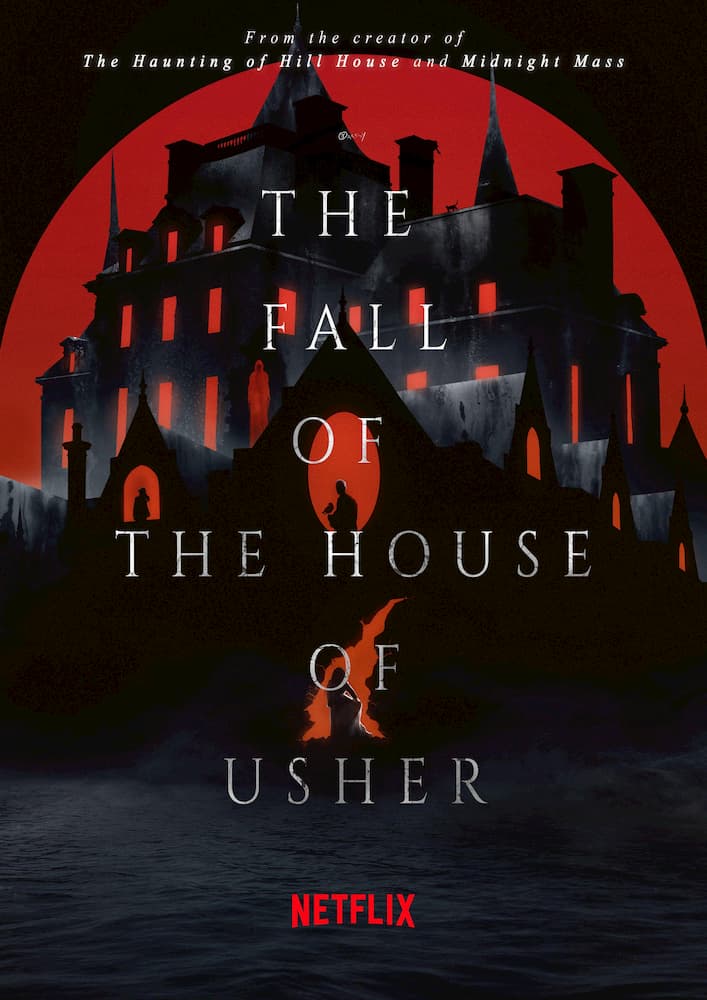

Now, sixty-three years after Corman’s ground-breaking movie reinvented Poe and the American Gothic, writer and director Mike Flanagan has done it again with his remarkable reimagining of The Fall of the House of Usher for Netflix. And the critical and commercial response has been much the same as it was in 1960. You must have seen the headlines, the memes, and the clickbait. The Fall of the House of Usher has gone viral. It quickly captured the top spot for the week among all Netflix movies and TV shows, with 65.3 million viewing hours and 7.9 million views. The Daily Mail, meanwhile, has already denounced it as ‘Netflix’s most depraved show’, and the paper is not alone in colourful reviews around the world that (wrongly) suggest this is the most ‘terrifying’, ‘perverted’, and ‘violent’ TV show ever made. It isn’t, at least not to seasoned fans of contemporary horror, but you can’t buy publicity like that, and the series has transcended its genre to gain mainstream views and attention, making it a significant media event. As Poe once noted, ‘The nose of a mob is its imagination. By this, at any time, it can be quietly led.’

Vincent Price as Roderick Usher, 1960

Flanagan hit the ground running as an innovative horror filmmaker with Absentia in 2011, which was initially funded through the crowdfunding website Kickstarter. This was followed by Oculus, Hush, Before I Wake and Ouija: Origin of Evil in 2016, and the adaptation of two novels by Stephen King, Gerald’s Game (2017) and Doctor Sleep (2019), the sequel to The Shining. He also made the miniseries Midnight Mass for Netflix (2021), a thoughtful and moving meditation on grief, guilt, and the possibility of redemption in which a priest suffering from dementia mistakes a vampire for an angel; and The Midnight Club (Netflix, 2022), based on the supernatural stories of the YA author Christopher Pike, which is so much more original than Disney’s reboot of Goosebumps.

In terms of elegant literary gothic revisionism, this is not Flanagan’s first rodeo either. As the creator, director, and lead writer of the ten-part serial The Haunting of Hill House for Netflix in 2018, Flanagan took his inspiration from the novel of the same name by Shirley Jackson (1959, previously filmed by Robert Wise in 1963 and Jan de Bont in 1999). Though not an adaptation of Jackson’s novel, Flanagan uses the original premise to explore the long-term effects of ‘the haunting’ on five siblings whose parents tried to renovate Hill House in the early 90s. It is a complex family saga with a non-linear narrative moving between different point-of-view characters in the present and their childhood memories, all stories leading to a key night in 1992 when the family finally fled the house. This is a structure that Flanagan seems to favour in his TV work – the longer running time of a series allowing for complex character arcs, subplots, and a much wider timeframe than a movie – and he returned to it in his next Netflix ‘Haunting’ series, The Haunting of Bly Manor in 2020. Credited as ‘inspired by the work of Henry James’, Bly Manor is a more ambitious literary project than Hill House in that rather than producing an almost entirely original story that took the essence of a single novel, Flanagan uses The Turn of the Screw (updated to the 1980s) as the foundational plot, the ‘through line’ of the series, but then also plunders eight more of James’ (mostly) supernatural short stories as episodes in the lives of his central characters and the history of Bly Manor. This approach to the American literary gothic is then developed further in the intertextual tour de force of The Fall of the House of Usher, in which numerous Poe poems and stories (and his biography) are referenced and quoted, creating an original contemporary drama that is seeped in his literary essence. Poe loved cyphers and so does Flanagan, packing the show with enough easter eggs to keep a Poe scholar up all night wondering if they caught all of them.

As with Hill House and Bly Manor, Flanagan’s House of Usher is not a straight adaptation of Poe. For that, you still need to go to the best of the Corman/Price movies. Again, Flanagan has gone with the gothic family saga, updating the Ushers to Biden’s America as a phenomenally wealthy and powerful dynasty with the 73-year-old Roderick Usher at its head (played by Flanagan regular Bruce Greenwood, his long face and grey widow’s peak recalling Price). Roderick rules in tandem with his brilliant and ruthless twin sister Madeline (Battlestar Galactica’s Mary McDonnell), while his six children (two legitimate, four not, and each uniquely dreadful), compete for his approval and their inheritance. The scenario is similar to Succession and Knives Out, while also inviting us to think of real-life corporate dynasties such as the Murdochs and the Trumps, vast business empires in which, like the Mafia, family is everything. ‘The company,’ Roderick tells his children, ‘is the family.’

The Usher fortune comes from Big Pharma, the foundation of which is the highly addictive painkiller ‘Ligadone’ (the name a nod to Poe’s ‘Ligeia’), a fictionalised version of OxyContin, referencing America’s current Opioid Crisis. In this context, Usher’s company Fortunato Pharmaceuticals (‘Fortunato’ being the victim of Poe’s 1846 revenge tragedy ‘The Cask of Amontillado’) alludes to Purdue Pharma and its billionaire former CEO Richard Sackler, himself the subject of two contemporary miniseries, Painkiller (Netflix) and Dopesick (Hulu). Purdue Pharma manufactured opium-based medications like hydromorphone, fentanyl, codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone (‘OxyContin’), using aggressive marketing and generous enticements to medical practitioners to prescribe OxyContin in particular, cornering the US market, generating staggering profits and resulting in half-a-million deaths by overdose in the US between 1999 and 2020. 1000+ lawsuits across multiple States finally pushed the company into bankruptcy pending a Department of Justice appeal to the US Supreme Court. The Sacklers have been described in the US media as the ‘worst drug dealers in history’ and the ‘most evil family in America’. In 2021, Purdue Pharma announced that it would be rebranding as Knoa Pharma, a cynical move worthy of Fortunato’s CEO and COO.

Poster for the 2023 Netflix adaptation.

At the start of the first episode (‘A Midnight Dreary’), which I think it is thus OK to reveal here, we learn two things that trigger the main story. Firstly, Roderick is on trial. Assistant United States Attorney C. Auguste Dupin (named, of course, for Poe’s famous French detective), is bringing 73 separate charges – one for each year of Roderick’s life – against the ‘Usher Crime Family’ pertaining to corruption and 50,000 unlawful deaths through Ligadone. Again, we are invited to think of Donald Trump as much as Sackler, who at time of writing has been criminally indicted four times and faces 91 felony counts across four criminal trials along with one civil suit. The earnest and meticulous Dupin (Carl Lumbly) is therefore a Jack Smith figure, pitted against Roderick’s legal fixer, Arthur Gordon Pym, Mark Hamill reminding us that there’s a lot more to him as an actor than Luke Skywalker. Pym is named for Poe’s 1838 novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, and Flanagan’s version has a similar tale to tell from an ill-fated expedition in the early 80s. The character would not look out of place in The Godfather, a Consigliere devoted to though not of the family: part lawyer, part spy, part hitman… whatever it takes to protect the Usher’s reputation and interests. They call him ‘The Pym Reaper’.

The second thing we learn is that all of Roderick’s children are dead, and have, in fact, died in the last two weeks. The opening scene is a family triple funeral, in which the eulogy is taken from Poe’s poem ‘Spirits of the Dead’ (1827):

Be silent in that solitude,

Which is not loneliness—for then

The spirits of the dead who stood

In life before thee are again

In death around thee—and their will

Shall overshadow thee: be still.

The spirits of the dead are around Roderick too. Periodically, he can see them, his mutilated children staring silently back at him. Leaving the service, Roderick collapses on the sidewalk on the way to his Limo, cryptically muttering ‘It’s time’ to Madeline as a raven watches implacably from the church’s facade. Roderick, apparently recovered, invites his nemesis Dupin (with whom he has a long history) to meet him at the house where he grew up – the physical ‘House of Usher’ – a derelict Carpenter’s Gothic, semiotically the quintessential American ‘haunted house’. This establishes a framing narrative which runs through the series until its climax, as Roderick ‘confesses his crimes’ and reveals the true causes of each of his children’s deaths while Madeline bangs about (offscreen) in the basement. This structure reflects Poe’s original story, in which the unidentified narrator sits for days with the greatly altered Roderick Usher in the ‘melancholy House’ as his childhood friend goes slowly out of his mind: ‘I shall ever bear about me a memory of the many solemn hours I thus spent alone with the master of the House of Usher.’ (In the show, Roderick has no friends; the closest thing he has is his oldest enemy.) Dupin records the increasingly surreal confession as both men share a bottle of €4 million Henri IV Dudognon Heritage Cognac – ‘You know, a single pour,’ Roderik tells Dupin, ‘it probably costs twice your annual salary.’ As they talk, Roderick’s only grandchild, Lenore, keeps desperately texting but he ignores her. Roderick’s story has two parallel arcs, one set in his past, going back to childhood, but focusing on events at the end of 1979 in which Dupin also played a part, the other documenting the previous two weeks, and the deaths of his children. Dupin immediately spots the point of view paradox here. How can Roderick know what happened to his kids? Roderick replies that they have told him.

Each episode takes its title and theme from a Poe story, except for Parts 1 and 8, which both reference his famous poem ‘The Raven’. These episodes bookend the serial and are concerned largely with Roderick and Madeline and the original ‘House of Usher’ story. The other six episodes each show the fate of one of Roderick’s six children, the titles signalling the broad content of the story: ‘The Masque of the Red Death’, ‘Murder in the Rue Morgue’, ‘The Black Cat’, ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’, ‘Goldbug’ (an interesting and unusual choice, although the episode takes more from Poe’s doppelgänger story ‘William Wilson’), and ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’. Poe aficionadas will therefore have a rough idea of how each sibling will meet their demise, although the updates are clever and surprising, yet in retrospect inevitable, which is always the best way to end a story. ‘The Masque of the Red Death’, for example, is transmuted from the Castle of Prince Prospero to an exclusive ‘pop-up club’ rave and orgy at a condemned Usher chemical plant, while the ‘Rue Morgue’ becomes ‘Roderick Usher Experimental’ (R.U.E.), a facility known to employees as the ‘Rue Morgue’ because of the animal tests undertaken there, including on chimpanzees. (You can see where this is going.) Then there are Poe stories within Poe stories; for example, in what happens to Morella, wife of Roderick’s first-born son Frederick and mother of Lenore, the only Usher grandchild, which takes elements from ‘Berenice’ and ‘The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar’ (and ‘Morella’ of course), while ‘The Cask of Amontillado’ features in Roderick’s rise to the top at Fortunato Pharmaceuticals. Frederick, meanwhile, is the name of a central character in Poe’s ‘Metzengerstein: A Tale in Imitation of the German’ (1832) and Morella comes from the story of the same name written by Poe in 1832. (You know who Lenore is.) Like Koch’s fractal snowflake, the intertext becomes almost infinite yet always constrained by the original circle: Poe, his life, his works.

The game continues with every character name, though as part of the fun is deciphering all these, I’ll just mention a few. Camille, Tamerlane, Prospero, and Annabel Lee are all obvious, but then there’s Victorine LaFourcade (‘The Premature Burial’), Alessandra (from the only play Poe ever wrote, the incomplete Politan, 1835), and crafty allusions to less well-known stories like ‘Never Bet the Devil Your Head’ (1841) and ‘Some Words with a Mummy’ (1845) which I’ll leave you to figure out. Then there’s the protean ‘Verna’, played with style and versatility by Carla Gugino, the enigmatic character that holds the whole plot together. More like Milton’s Satan – or ‘Rose the Hat’ from Doctor Sleep – than a creation of Poe, her name is an anagram of ‘Raven’.

There is also notable biographical naming. Roderick and Madeline are the illegitimate children of ‘William Longfellow’, for example. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, poet, author, and Smith Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard University once turned down an offer from Poe to contribute to Graham’s Magazine. Irked by Longfellow’s literary and academic success, and desirous of stirring up publicity, Poe initiated a long literary war in reviews that were brutal even by nineteenth century standards. Similarly, the original CEO of Fortunata, who uses and abuses Roderick and Madeline, is called Rufus Wilmot Griswold. The original Rufus Wilmot Griswold had replaced Poe as editor of Graham’s in 1842 and professionally they did not get on. Both were also rivals for the affection of the popular poet Frances Sargent Osgood (though all three were married at the time), and when Poe submitted ‘The Raven’ to Graham’s, Griswold turned it down. When Poe died in 1849, Griswold claimed that Poe had made him his literary executor, though in truth he had tricked Poe’s mother-in-law into signing the papers. He edited Poe’s first collected works, which made him more money than Poe ever had from his writing, while allowing him to bask in reflected literary glory. Griswold also contributed a ‘Memoir of the Author’ which depicted Poe as a depraved, drunken, opium-fuelled lunatic, through a series of entirely fictitious anecdotes, and selectively quoted, altered, or forged correspondence. The book was widely reprinted, and quickly became the standard biographical source on Poe, which accounts for the tendency to this day among fans to associate the author with his own gothic characters. Look harder, and you’ll also spot references to Poe’s family in the series, as well as the last words he ever spoke, hidden on nametags and driving licenses, Mise-en-scènically embedded.

Poe at work in the company of his cat, Catalina, and his wife and proof-reader, Virginia Eliza Clemm.

But the most biographical portrait in the series is Roderick Usher himself. His mother was called Eliza, as was Poe’s, and like Poe he’s an orphan, and very close to his sister. His young wife Juno hints at Poe’s child bride, Virginia Clemm, who was 13 when they married (Poe was 27), and like Poe he has heart problems. Most significantly, Roderick is a poet, or at least he was until a choice he made in 1979 sent his life off in a different direction to that which was, the mysterious Verna explains, his true destiny. Before this, he was an ordinary, honest office worker in the lower echelons of Fortunato, struggling to support a young family. Roderick was married to Annabel Lee, a good and warm-hearted woman to whom he quotes poetry based on their love. (For the purposes of the story, Roderick wrote ‘Annabel Lee’, ‘The Raven’ and ‘Lenore’, all of which are quoted at length alongside ‘Spirits of the Dead’, not Poe.) Like Poe, who lived a life of gentile poverty despite his reputation as a talented author and critic, Young Roderick is poor. How he became the ruthless billionaire businessman forms the heart of his confession, so you’ll have to watch the show to find out. I won’t spoil it. Let’s just say that the moral choices we make, and their consequences are a central theme, just as Flanagan explored through a more spiritual and religious lens in Midnight Mass. As Verna tells Prospero ‘Perry’ Usher:

‘There are always consequences. Take you, for instance. Someone, a long time ago, made a little decision, then another, then a big one, then one of absolutely no importance. And then by and by, you were born. On that day, you were the consequence of a harmless choice made by someone in a moment where you didn’t even exist. And that choice defined your whole life. You are consequence, Perry. And tonight, you are consequential.’

As Roderick says in Poe’s original story, ‘I dread the events of the future, not in themselves, but in their results.’ So, Roderick the struggling poet and the two loving kids he has with Annabel Lee are overwritten by Roderick the feared, all-powerful oligarch (apparently immune to prosecution), a useless yes-man of a son, and a lifestyle influencer daughter who’s even more vapid than Gwyneth Paltrow, their goodness, Roderick tells Dupin, ‘killed by the money.’ (Only Lenore is like her virtuous grandmother; she wants to use the money to help people.) As Verna explains, this is all about, ‘Who you are, were, and could have been.’ And as he chose profit and power over love, Roderick’s first marriage collapsed leaving a trail of illegitimate children who are all messed up, narcissistic rich kids that it’s difficult to feel any sympathy for as they meet their grisly ends. As Ben Travers of IndieWire wrote in his review of House of Usher: ‘As the absurdly wealthy destroy our only planet, our innocent pleasures, and our very lives, even a blunt, overextended allegory can deliver visceral satisfactions. Arguing billionaires should not exist has rarely felt so Biblical.’ As the honest, hardworking Dupin walks away from the Usher graves at the end of the final episode, to return to his husband, kids, and grandkids, the moral of the story is plain. This kind of wealth and power corrupts utterly. This kind of money buys an easy life, but not happiness.

Perhaps not. Flanagan doesn’t let us off the hook quite so easily. In one of the philosophical monologues he is fond of giving his characters, Madeline argues that the fault lies not with her class but our own:

‘These people. They want an entire meal for $5 in five minutes then complain when it’s made of shit and plastic. McDonald’s would serve nothing but kale salad all day and all night long if that’s what people f—ing ate. It’s available, no one buys it … And what do we teach them to want? Houses they can’t afford. Cars that poison the air. Single-serve plastics, clothes made by starving children in third world countries, and they want it so bad that they’re begging for it, they’re screaming for it, they’re insisting upon it. And we’re the problem? These f—ing monsters, these f—ing consumers, these f—ing mouths. They point at you and me like we’re the problem. They f—ing invented us. They begged for us, they’re begging for us still. So I say, we stand tall and proud, brother.’

And in this self-justifying tirade, you have to admit that she has a point. As the Dead Kennedys sang, ‘Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death!’ This is the world we live in, and apparently the one we want. As Verna also argues:

‘So much money. One of my favourite things about human beings. Starvation, poverty, disease, you could fix all that, just with money. And you don’t. I mean, if you took just a little bit of time off the vanity voyages, pleasure cruising, billionaire space race, hell, you stopped making movies and TV for one year and you spent that money on what you really need, you could solve it all. With some to spare.’

While, as Ben Travers suggests, Flanagan has fun punishing the billionaires in a blatant modern political allegory, he is also asking us why we allow this destructive inequality to continue? Let’s face it, a lot of folks in democratic countries keep on voting for the billionaires and don’t seem much bothered when the billionaires give up on democracy altogether as Vladimir Putin did in Russia. Donald Trump, for example, has made no secret of his plans to turn the United States of America into a dictatorship and his support among working class voters remains massive. Flanagan even throws in a joke about him doing a deal with Verna: ‘Like I said to one of my clients, when I’m done, you can stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody, and it won’t cost you a thing.’ (At a campaign rally in Iowa in 2016, Trump had boasted, ‘I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody. And I wouldn’t lose any voters.’) We pay tax so men like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos don’t have too, and we keep on consuming Rupert Murdoch’s media empire. As Madeline seems to suggest, following Joaquin Phoenix’s Trump era Joker, we ‘get what we f—ing deserve!’

For me, then, the most frightening scene in The Fall of the House of Usher has nothing to do with madness, premature burials, vengeful revenants, or homicidal test apes. Instead, it is the scene in which Roderick encapsulates in a single extended metaphor the world we now find ourselves living in. It is worth quoting in full. When Roderick begins a point, ‘When life hands you lemons…’ Dupin automatically replies, ‘You make lemonade.’ That’s the expression, right? ‘No,’ says Roderick, continuing:

‘First, you roll out a multimedia campaign to convince people lemons are incredibly scarce, which only works if you stockpile lemons, control the supply, then a media blitz. Lemon is the only way to say, “I love you,” the must-have accessory for engagements or anniversaries. Roses are out, lemons are in. Billboards that say she won’t have sex with you unless you got lemons. You cut De Beers in on it. Limited edition lemon bracelets, yellow diamonds called “lemon drops”. You get Apple to call their new operating system “OS-Lemón”. A little accent over the “o”. You charge 40 per cent more for organic lemons and 50 per cent more for conflict-free lemons. You pack the Capitol with lemon lobbyists; you get a Kardashian to suck a lemon wedge in a leaked sex tape. Timothée Chalamet wears lemon shoes at Cannes. Get a hashtag campaign. Something isn’t “cool”, “tight”, or “awesome”. No, it’s “lemon”. “Did you see that movie? Did you go to that concert? It was effing lemon.” Billie Eilish, “OMG, hashtag lemon.” You get Dr. Oz to recommend four lemons a day and a lemon suppository supplement to get rid of toxins ’cause there’s nothing scarier than toxins. Then, you patent the seeds. You write a line of genetic code that makes lemons look just a little more like tits and you get a gene patent for the tit-lemon DNA sequence, you get those seeds circulating in the wild, and then you sue the farmers for copyright infringement when that genetic code shows up on their land. Sit back, rake in the millions, and then, when you’re done, and you’ve sold your lempire for a few billion dollars, then, and only then, you make some f—ing lemonade.’

Poe never wrote anything quite as chilling as this, although I suspect the lemon monologue would have appealed to him as an accomplished satirist.

Bruce Greenwood as Roderick Usher in the 2023 production

In Poe’s original story, ‘the quaint and equivocal appellation of the “House of Usher”’ came to include ‘both the family and the family mansion’, while Roderick’s ‘disordered fancy’ ascribed ‘sentience’ to the building itself: ‘The result was discoverable, he added, in that silent, yet importunate and terrible influence which for centuries had moulded the destinies of his family, and which made him what I now saw him—what he was.’ The house therefore collapses into its own reflection in the story’s famous concluding image:

…my brain reeled as I saw the mighty walls rushing asunder—there was a long tumultuous shouting sound like the voice of a thousand waters—and the deep and dank tarn at my feet closed sullenly and silently over the fragments of the ‘House of Usher.’

The ‘House of Usher’ is both the family line and the ‘living’ building itself, its unconscious presence signalled in Poe’s opening paragraph with ‘the vacant eye-like windows’. Its ‘sentience’ is that of ‘vegetable things’, ‘gray stones’, and ‘fungi’, rather than something as straightforward as malevolent consciousness. Like the ‘black and lurid tarn’ it sits by, what’s in there lies beneath the surface. As Roderick understands – though his reason ‘totters upon her throne’ so this could just all be delusion – his ancestors, his sister and himself are all tied to the house and it to them. And just as it sucks the life and colour out of the land around it, it sucks the life and colour out of them. It is ‘The Haunted Palace’. In his seminal essay ‘Supernatural Horror in Literature’ (1927), H.P. Lovecraft suggested that Roderick, Madeline, and the ancient house all shared ‘a single soul’, meeting ‘one common dissolution at the same moment.’ The House of Usher, then, can be a metaphor for the unconscious, for all those destructive desires and monsters from the id, and in that sense, it stands for all of us, not just Roderick and Madeline. It is not so difficult to take another step back from this position, and to see the world itself in those bleak walls with the ‘barely perceptible fissure’ zigzagging down from the roof (the head, the conscious mind) until ‘it became lost in the sullen waters of the tarn’ (the unconscious) that would one day bring the entire house down.

‘A poem,’ says Verna, ‘is a safe place for a difficult truth.’ Morally, politically, and metaphysically, this seems to me the point of Flanagan’s House of Usher. It is, like ‘The Raven’, a stylised narrative poem, as is much of Flanagan’s remarkable screenwriting, and, arguably, everything Poe ever wrote. Flanagan is not Poe, but he clearly loves him and knows his work very well. And like Poe, there’s a ghoulish delight in the mad and macabre that characterises all the truly great gothic writers. Flanagan is also an admirer (and adapter) of Stephen King, and like King he is operating in a literary and cinematic tradition that in many ways starts with Poe in the US, but which also owes much to pulp writers like Lovecraft and Matheson, EC horror comics, The Twilight Zone, and the films of Roger Corman and George A. Romero, to name but a few. Adapting Poe in 2023 is unlikely to be to the tastes of the purists. That said, the original sensibility remains. If you love Poe, you may still love Flanagan’s interpretation, however notionally different to the original source material. If you don’t know Poe’s original stories, then Flanagan’s miniseries isn’t a bad introduction that should inspire you to seek out and read some of the most important and amazing gothic fiction ever written. Flanagan does not allow himself to be constrained by the original texts, but he pays his respects. And in updating Poe, he makes the ‘House of Usher’ into the world as it is today, and as did Poe in 1839, invites us to consider the choices we’ve made that have bought us to this point. Do we want a world built by billionaires or by poets?

Dr Stephen Carver

Main image: Carla Gugino in The Fall of the House of Usher, directed by Mike Flanagan. Credit: Intrepid Pictures / Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Vincent Price in the 1960 film. Credit: Allstar Picture Library Limited. / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Poster for the 2023 Netflix release. Credit: TCD/Prod.DB / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: An early printed image of Edgar Alan Poe working at his desk with his pet cat Catalina on his shoulder with Virginia Eliza Clemm, (his juvenile cousin, wife and proof reader) in the chair. Credit: Colin Waters / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: Bruce Greenwood as Roderick Usher 2023. Credit: Photo: Eike Schroter / ©Netflix / Courtesy Everett Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

For more information on Poe’s work, visit the website of The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore

Books associated with this article