Scene at Christmas

David Stuart Davies looks at festive moments in literature.

It is perhaps not surprising that many writers have included a Christmas scene or passage in their novels. It is a time of year when passions are roused and the potential for great comedy or chilling melodrama is rife. Christmas is like an isolated moment in time, removed from the regular rhythm of the year and so provides the creative artist with an almost blank canvas to conjure their magic. So, I thought it would be pleasing to take a look at a few of these yuletide scenes.

Of course, the most obvious choice in the selection would be A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens, who manages through the course of this magical parable to provide a range of emotions from the highly amusing to the darkly chilling (think of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come). And the highly emotional; the closing scenes are real tear jerkers. However, it is a very well known narrative and so I have chosen another of Dickens’ great novels to mention: Great Expectations (1861), the story of young Pip and his journey through life. As a boy he lives with his shrewish sister and her husband on the marshes in Kent. One evening near Christmas he visits the graveyard where his parents are buried and is accosted by an escaped convict who orders the boy to bring him food and a file for his leg irons. The terrified Pip steals the file from amongst Joe’s tools and a pie and brandy that were meant for the big meal at Christmas. On the day at the festive lunch, Pip’s Uncle Pumblechook requests a glass of brandy, which he had diluted to cover up the theft. The scene is one of delightful tension:

‘My sister went for the stone bottle, came back with the stone bottle, and poured his brandy out: no one else taking any. The wretched man trifled with his glass,—took it up, looked at it through the light, put it down,—prolonged my misery. All this time Mrs. Joe and Joe were briskly clearing the table for the pie and pudding.

I couldn’t keep my eyes off him. Always holding tight by the leg of the table with my hands and feet, I saw the miserable creature finger his glass playfully, take it up, smile, throw his head back, and drink the brandy off. Instantly afterwards, the company were seized with unspeakable consternation, owing to his springing to his feet, turning round several times in an appalling spasmodic whooping-cough dance, and rushing out at the door; he then became visible through the window, violently plunging and expectorating, making the most hideous faces, and apparently out of his mind.

I held on tight, while Mrs. Joe and Joe ran to him. I didn’t know how I had done it, but I had no doubt I had murdered him somehow. In my dreadful situation, it was a relief when he was brought back, and surveying the company all round as if they had disagreed with him, sank down into his chair with the one significant gasp, ‘Tar!’

I had filled up the bottle from the tar-water jug. I knew he would be worse by and by. I moved the table, like a Medium of the present day, by the vigor of my unseen hold upon it.

‘Tar!’ cried my sister, in amazement. ‘Why, how ever could Tar come there?’’

It is the beginning of Pip’s extraordinary adventures in which the convict plays a major part.

There is tension also in the Christmas scene in Far from the Madding Crowd (1874) by Thomas Hardy who was a wizard at describing such occasions. Farmer Boldwood had organised a Christmas Eve party with the intention of using the occasion to propose to Bathsheba. She knew this and was dreading it. Hardy describes beautifully how Boldwood prepared for the party:

‘That the party was intended to be a truly jovial one there was no room for doubt. A large bough of mistletoe had been brought from the woods that day, and suspended in the hall of the bachelor’s home. Holly and ivy had followed in armfuls. From six that morning till past noon the huge wood fire in the kitchen roared and sparkled at its highest, the kettle, the saucepan, and the three-legged pot appearing in the midst of the flames like Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego; moreover, roasting and basting operations were continually carried on in front of the genial blaze.’

The richness of the party preparations contrast with the dark drama that occurs later. Read on!

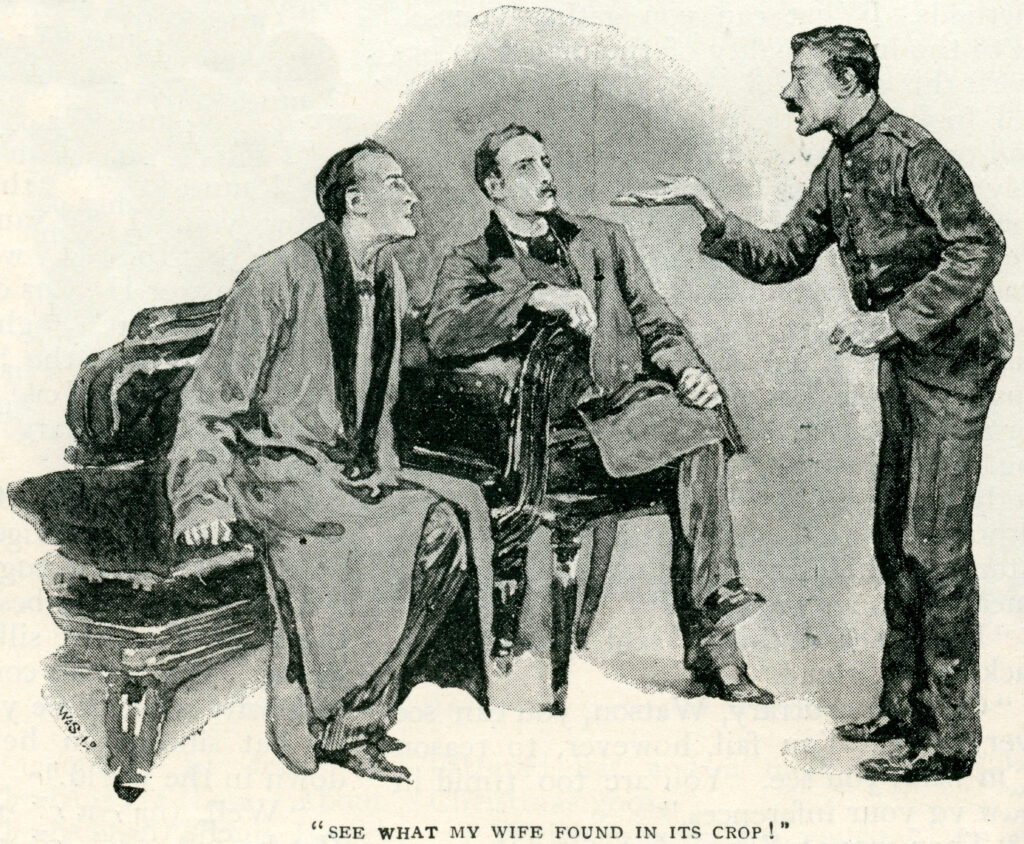

The Blue Carbuncle

The Blue Carbuncle (1892) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, which features Sherlock Holmes, of course, is set in snowy December and is, as one critic remarked, ‘a Christmas story without slush.’ Doyle captures the nature of a cold and icy yuletide in Victorian London as Holmes sets out from Baker Street on his investigation:

‘It was a bitter night, so we drew on our ulsters and wrapped cravats about our throats. Outside, the stars were shining coldly in a cloudless sky, and the breath of the passers-by blew out into smoke like so many pistol shots. Our footfalls rang out crisply and loudly as we swung through the doctors’ quarter, Wimpole Street, Harley Street, and so through Wigmore Street into Oxford Street. In a quarter of an hour we were in Bloomsbury at the Alpha Inn, which is a small public-house at the corner of one of the streets which runs down into Holborn. Holmes pushed open the door of the private bar and ordered two glasses of beer from the ruddy-faced, white-aproned landlord.’

And so to America to sample a small part of the Christmas featured in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868). Four sisters and their mother live in Massachusetts in genteel poverty. Their father is away serving as a chaplain for the Union Army in the American civil war. The charm of the book is the way this family overcome their own hardships and always help others. On Christmas day they ventured out with baskets of food to feed the hungry children. In the evening they entertained themselves by putting on their own plays:

‘The morning charities and ceremonies took so much time that the rest of the day was devoted to preparations for the evening festivities. Being still too young to go often to the theatre, and not rich enough to afford any great outlay for private performances, the girls put their wits to work, and necessity being the mother of invention, made whatever they needed. Very clever were some of their productions, pasteboard guitars, antique lamps made of old-fashioned butter boats covered with silver paper, gorgeous robes of old cotton, glittering with tin spangles from a pickle factory, and armour covered with the same useful diamond shaped bits left in sheets when the lids of preserve pots were cut out.’

The heroine of Jane Eyre (1847) by Charlotte Brontë experiences two contrasting Christmases during the course of the novel. In one, she is ignored and isolated as an unwanted intruder by her aunt and cousins:

‘From every enjoyment I was, of course, excluded: my share of the gaiety consisted in witnessing the daily apparelling of Eliza and Georgiana, and seeing them descend to the drawing-room, dressed out in thin muslin frocks and scarlet sashes, with hair elaborately ringletted; and afterwards, in listening to the sound of the piano or the harp played below, to the passing to and fro of the butler and footman, to the jingling of glass and china as refreshments were handed, to the broken hum of conversation as the drawing-room door opened and closed. When tired of this occupation, I would retire from the stairhead to the solitary and silent nursery.’

Christmas in ‘Little Women’

However, later in the story, before she is reunited with her beloved Rochester, she spends Christmas at Moor House with her friendly cousins, Mary and Diana:

‘It was Christmas week: we took to no settled employment, but spent it in a sort of merry domestic dissipation. The air of the moors, the freedom of home, the dawn of prosperity, acted on Diana and Mary’s spirits like some life-giving elixir: they were gay from morning till noon, and from noon till night.’

I will leave you with perhaps my favourite Christmas snapshot from a work of fiction. It is a scene in The Wind in the Willows (1908). Kenneth Grahame’s magical book is certainly a children’s story but it appeals to grown ups as well. Not only is it an enchanting tale of anthropomorphised animals and their adventures but also a strong definition of the power and life afforming bond of friendship and one’s ability to achieve one’s potential if one puts one’s mind to it. At one point in the story Mole and Ratty get lost in the Wild Wood during a snowstorm and end up in Mole’s old quarters underground where they set themselves a simple meal. It is near Christmas and as they tuck into their food…

‘…sounds were heard from the fore-court without—sounds like the scuffling of small feet in the gravel and a confused murmur of tiny voices, while broken sentences reached them—’Now, all in a line—hold the lantern up a bit, Tommy—clear your throats first—no coughing after I say one, two, three.—Where’s young Bill?—Here, come on, do, we’re all a-waiting—’

‘What’s up?’ inquired the Rat, pausing in his labours.

‘I think it must be the field-mice,’ replied the Mole, with a touch of pride in his manner. ‘They go round carol-singing regularly at this time of the year. They’re quite an institution in these parts. And they never pass me over—they come to Mole End last of all; and I used to give them hot drinks, and supper too sometimes, when I could afford it. It will be like old times to hear them again.’

‘Let’s have a look at them!’ cried the Rat, jumping up and running to the door.

It was a pretty sight, and a seasonable one, that met their eyes when they flung the door open. In the fore-court, lit by the dim rays of a horn lantern, some eight or ten little fieldmice stood in a semicircle, red worsted comforters round their throats, their fore-paws thrust deep into their pockets, their feet jigging for warmth. With bright beady eyes they glanced shyly at each other, sniggering a little, sniffing and applying coat-sleeves a good deal. As the door opened, one of the elder ones that carried the lantern was just saying, ‘Now then, one, two, three!’ and forthwith their shrill little voices uprose on the air, singing one of the old-time carols that their forefathers composed in fields that were fallow and held by frost, or when snow-bound in chimney corners, and handed down to be sung in the miry street to lamp-lit windows at Yule-time.’

I’ve always wished those field mice would come round to my house at Christmas-time.

Of course I have only scratched the surface of the range of Christmas scenes in literature but I hope I’ve given you a flavour of them and perhaps the inspiration to pick up one of these novels to see exactly how the festive moment fits snugly within the whole. Merry Christmas reading.

Main image: The field mice carol singing from The Wind in the Willows Credit: Mick Durham FRPS / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: “See what my wife found in its crop!”; The Blue Carbuncle 1892 Credit: Baker Street Scans / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Christmas in Little Women, from the 1994 film Credit: Photo 12 / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

Great Expectations (Collector’s Edition)

Charles Dickens

Far From The Madding Crowd (Collector’s Edition)

Thomas Hardy

Far from the Madding Crowd

Thomas Hardy

Great Expectations

Charles Dickens

Little Women (Luxe Edition)

Louisa May Alcott

Little Women (Exclusive)

Louisa May Alcott

Little Women (Collector’s Edition)

Louisa May Alcott

Little Women & Good Wives (Children’s)

Louisa May Alcott

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Collector’s Edition)

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Adventures & Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Jane Eyre (Luxe Edition)

Charlotte Brontë

Jane Eyre (Collector’s Edition)

Charlotte Brontë

The Wind in the Willows

Kenneth Grahame

The Wind in the Willows (Exclusive)

Kenneth Grahame