Books by Thomas Hardy

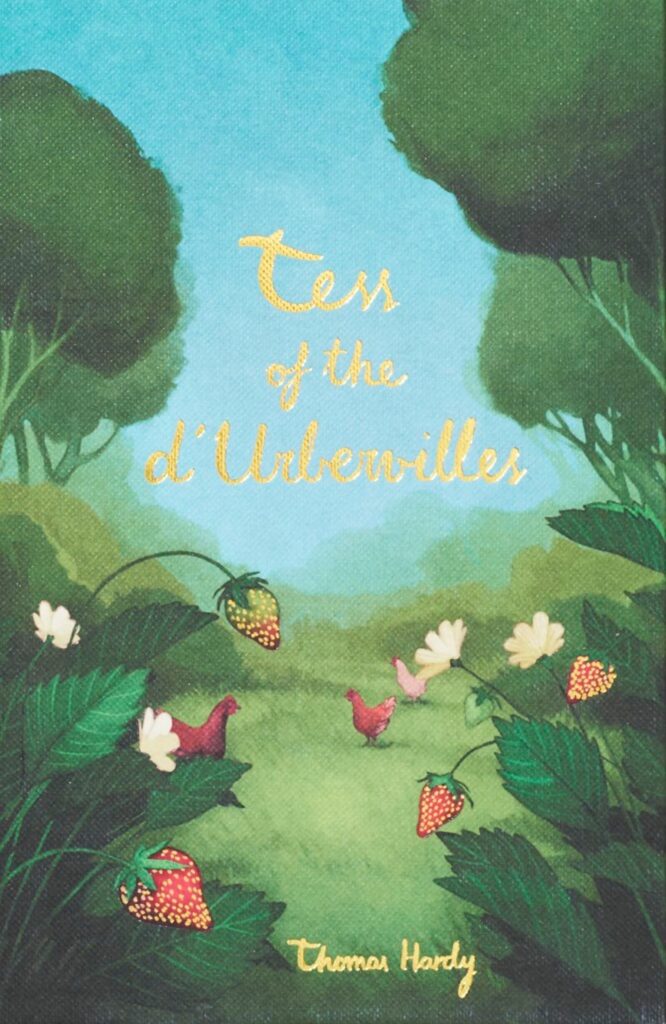

Tess of the D’urbervilles (Collector’s Edition)

Collector's Editions

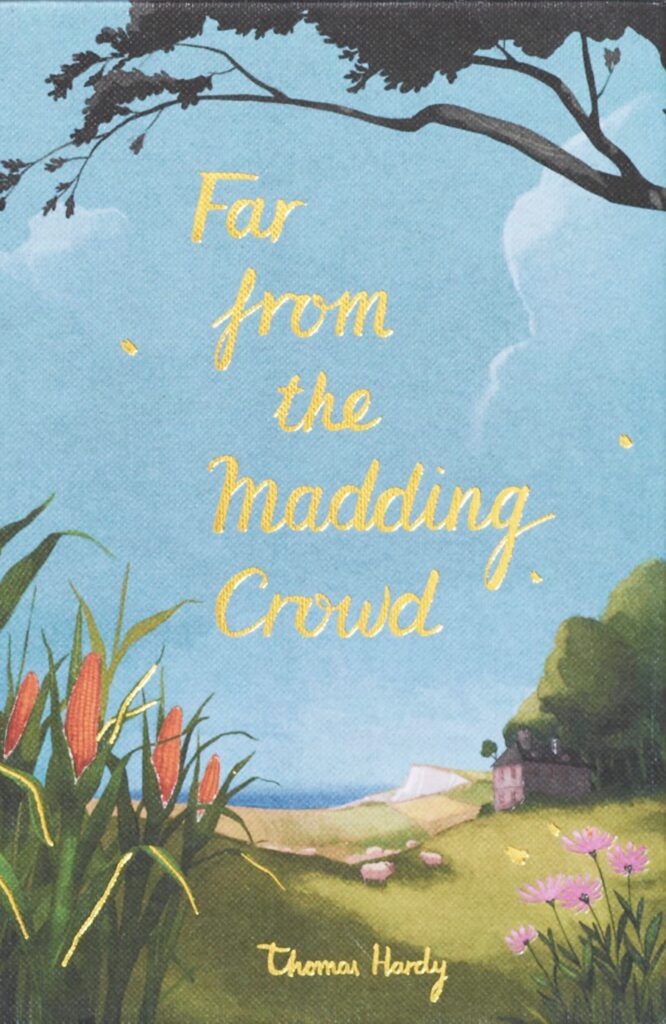

Far From The Madding Crowd (Collector’s Edition)

Collector's Editions

Desperate Remedies

Classics

Far from the Madding Crowd

Classics

Jude the Obscure

Classics

Life’s Little Ironies

Classics

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Classics

A Pair of Blue Eyes

Classics

The Return of the Native

Classics

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Classics

The Trumpet-Major

Classics

Under the Greenwood Tree

Classics

Wessex Tales

Classics

The Woodlanders

Classics