Sumer is icumen in – finally.

Sally Minogue reflects on evocations of Summer by some Wordsworth authors.

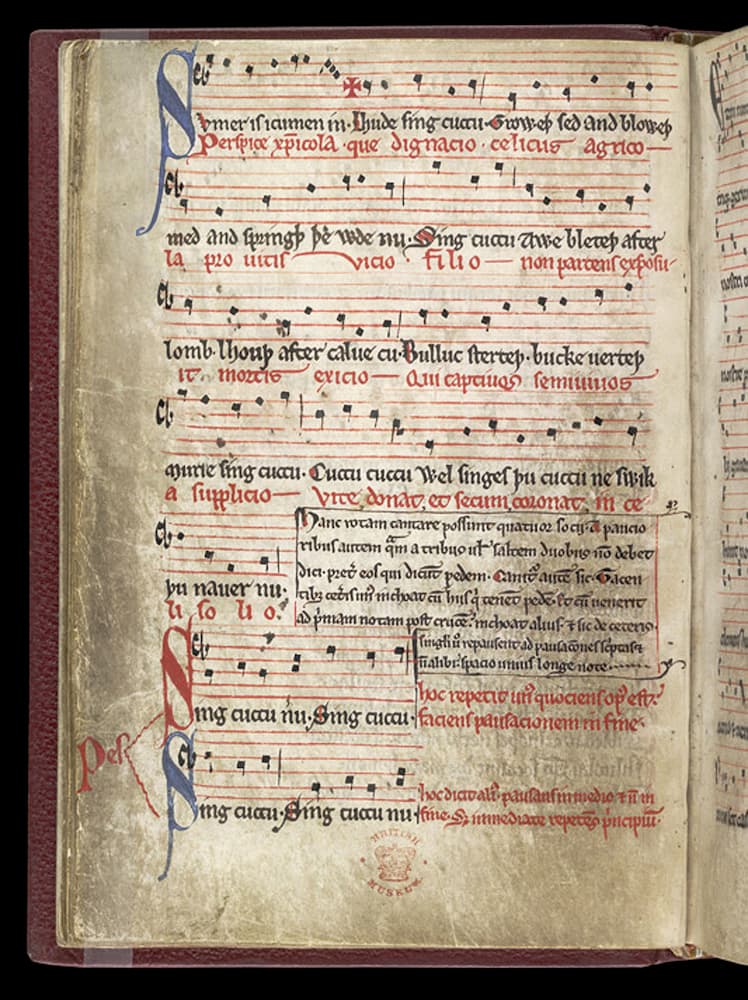

‘Sumer is icumen in –/ Lhude sing! cuccu.’ Not by one of Wordsworth’s authors, but by one of that large and motley crew, Anon., this early 13th century lyric is still widely recognized because it was set to music and is still sung today. It is often sung as a round, a strange form where one line is sung on top of another making a sort of vocal tapestry. (You might have sung a round at primary school; that’s the last time I sang one – Oranges and Lemons is a common one.) It’s a song which still captures the exuberance felt when everything starts to burgeon, that fresh green leaf on the trees, the first buds and shoots unfurling, blossom suddenly everywhere. Here in Kent, the May blossom is now at its height and it carries an undeniable freight of the pagan. It’s actually the blossom of the humble hawthorn and its extravagance is almost at odds with its ordinary origins (as children we called the early leaves, which could be eaten, ‘bread and cheese’). But hawthorn has ancient associations with May Day, and the regeneration of nature, including fertility and the rituals that were believed to engender it. The May blossom this year may be a long way after May 1st, but this has been an uncommonly late year. (Its connection with May 1st may also be attributed to the Julian calendar, changed to the Gregorian in 1752, when the old May 1st became equivalent to today’s May 12th.)

MS c. 1260-1270

Thomas Hardy, always quick to pick up on folkloric traditions, whilst maintaining a sceptical stance to them, deliberately first introduces us to Tess in Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) when she is taking part in a May Day rite, though one that is already decaying – ‘metamorphosed or disguised’. But Angel Clare, who is later to re-meet Tess and woo her, is charmed by the simple rural spectacle, and by the young girls in their vestal white. (Chapter 2) That early vision of a virginal Tess is made flesh when he meets her again at Dairyman Crick’s where they are both working. And now Hardy invokes summer full-bloodedly:

The season developed and matured. Another year’s instalment of flowers, leaves, nightingales, thrushes, finches, and other such ephemeral creatures, took up their positions … Rays from the sunrise drew forth the buds and stretched them into long stalks, lifted up sap in noiseless streams, opened petals, and sucked out scents in invisible jets and breathings. (Chapter 20)

In this fecund atmosphere, Angel and Tess meet each early morning, brought together innocently by the act of milking, when ‘the spectral, half-compounded, aqueous light which pervaded the open mead, impressed them with a feeling of isolation, as if they were Adam and Eve’. So both pagan and Christian resonances have been invoked for Angel by Tess, in association with the midsummer of the natural world. But as the season wends on, the atmosphere becomes ‘stagnant and enervating’, and ‘as Clare was oppressed by the outward heats, so was he burdened inwardly by waxing fervour of passion for the soft and silent Tess’. In Hardyesque fashion, the turning season is used to evoke a sense of unease, of the rot that is to come. The evocation of perfect early summer in the early morning meetings of Angel and Tess, for the humble business of milking, is undermined, as their love is to be undermined by Tess’s secret. As so often with Hardy, once the whole novel has revealed itself, that first innocent May Day scene when Angel first glimpses Tess is riven with irony.

Tess

Hardy characteristically uses the seasons to reflect the nature of a relationship, often drawing on the heat and promise of summer to echo sensual feelings and to hint at sexual attractions which he was unable, because of the pressures of moral censorship, to explore as fully as he might have wished. In Far From the Madding Crowd (1874), he chooses a ‘midsummer evening’ for the highly-charged encounter between Bathsheba Everdene and Sergeant Troy which will lead to their infatuation and an eventually tragic marriage.

The hill opposite Bathsheba’s dwelling extended, a mile off, into an uncultivated tract of land, dotted at this season with tall thickets of brake fern, plump and diaphanous from recent rapid growth, and radiant in hues of clear and untainted green.

At eight o’clock this midsummer evening, whilst the bristling ball of gold in the west still swept the tips of the ferns with its long, luxuriant rays, a soft brushing-by of garments might have been heard among them, and Bathsheba appeared in their midst, their soft, feathery arms caressing her up to her shoulders. (Chapter 28)

Hardy cleverly prefigures what is to come; the images of the setting sun catching the tips of the ferns with its light, and of the ferns themselves ‘caressing’ Bathsheba, are both to be echoed in Troy’s flashing swordplay around her body. The tip of the sword, catching the sun’s brilliance, ‘above, around, in front of her, well-nigh shut out earth and heaven. … In short, she was enclosed in a firmament of light, and of sharp hisses, resembling a sky-full of meteors close at hand.’ No wonder that the impressionable young woman ‘felt powerless to withstand or deny him’. This is writing of a brilliance equal to Troy’s swordplay, and in fact more powerful and evocative than many a more explicit depiction of a sexual encounter.

Stooks of oats

D.H. Lawrence, in some ways a direct descendant of Hardy, could, and of course would write in a more open way about desire and its fulfilment. But he too uses the seasons and nature to lead up to his sexual encounters. I have written recently about his touching use of the natural world in Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) In his earlier novel The Rainbow (1915), one of the most powerful scenes is that in which Anna and Will Brangwen stook sheaves in the moonlight – a late summer harvest scene – moving separately but inevitably towards each other in the natural rhythm of lifting the sheaves of oats into stooks:

They worked together, coming and going, in a rhythm, which carried their feet and their bodies. She stooped, she lifted the burden of sheaves, she turned her face to the dimness where he was, and went with her burden over the stubble. … And there was the flaring moon laying bare her bosom again, making her drift and ebb like a wave.

He worked steadily, engrossed, threading backwards and forwards like a shuttle across the strip of cleared stubble, weaving the long line of riding shocks, … threading his sheaves with hers.

And the work went on. The moon grew brighter, clearer, the corn glistened. …

Till at last, they met at the shock, facing each other, sheaves in hand.

Lawrence develops the scene carefully and slowly but insistently, until finally the two meet in an embrace, one which will also end in marriage. As in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and befitting his modernist status, Lawrence here emphasizes the equality of woman and man (here Anna and Will), unlike the comparative passivity of both Tess and Bathsheba in the scenes I’ve discussed.

Both Hardy and Lawrence evoke summer both realistically and symbolically; the latter would work less well without the former. Other writers evoke it for the beauty of the natural setting and season. Elizabeth Gaskell opens Mary Barton (1848), her ‘Tale of Manchester Life’, with the surprise of a bucolic scene:

There are some fields near Manchester, well known to the inhabitants as ‘Green Heys Fields’, through which runs a public footpath to a little village about two miles distant. In spite of these fields being flat, and low, nay, in spite of the want of wood … there is a charm about them which strikes even the inhabitant of a mountainous district, who sees and feels the effect of contrast in these commonplace but thoroughly rural fields, with the busy, bustling manufacturing town he left but half-an-hour ago. … Here in their seasons may be seen the country business of haymaking, ploughing, etc, which are such pleasant mysteries for townspeople to watch: and here the artisan, deafened with noise of tongues and engines, may come to listen awhile to the delicious sounds of rural life: the lowing of cattle, the milkmaid’s call, the clatter and cackle of poultry in the old farmyards. (Chapter 1)

This is a very different kind of writing from our other examples. Gaskell is of course the earliest of these writers, working in a particular genre, the social novel, and even in her natural descriptions we feel a certain political import. Most notably she is showing the great need for those living and working in the newly industrialised towns for the tranquil resource of the countryside, and their pleasure in keeping contact with ‘country business’ and its ‘pleasant mysteries’. The ‘delicious sounds’ of the fields are contrasted with the deafening ‘noise’ of the town. Later in the passage she mentions the way those walking here gather by a particular stile, because of its proximity both to ‘a deep, clear pond’ and to a rambling farmyard and ‘old world’ farmhouse. ‘The porch of this farmhouse is covered by a rose-tree; and the little garden surrounding it is crowded with a medley of old-fashioned flowers … allowed to grow in scrambling and wild luxuriance.’ Cultivation and nature merge into one, ‘the most republican and indiscriminate order’ of the garden spilling into a field with a hedge of hawthorn (our May) and blackthorn and thence to the stile where ‘primroses may often be found, and occasionally the blue sweet violet on the grassy hedge bank’. On ‘this early May evening’ the fields are ‘thronged’ as ‘the softness of the day tempted forth the young green leaves which almost visibly fluttered into life’. Gaskell has barely hinted at the harshness, poverty and disease of urban factory life, but we as readers are immediately clear that these fields and the footpath through them – the right of way – are a vital source of well-being and a much-needed escape for these workers from the crammed mills, streets and houses to which they must return. The rest of the novel will dwell on these, but it is clever of Gaskell to start here – with what the town is not.

The same features are touched on by Gaskell here as by Hardy and Lawrence – the work of the country, milking, haymaking, harvesting, and the beauties of early summer as the natural world ‘visibly’ flutters into life. But there is none of the mythological or romantic aura which we find in Hardy and Lawrence – interestingly writing considerably later, yet with a much fuller sense of the traditional rhythms of rural life. Gaskell may begin with nature and its importance, but it is very much in the context of the industrialised town which has grown up within these fields. It is interesting to note that the ‘Green Heys Fields’, now long gone, remain only in the shape of a Manchester street name, ‘Greenheys Lane’. It was with the social effects and conditions of urban life that Gaskell was centrally concerned.

Tintern Abbey

I can’t write a blog on evocations of summer without mention of the Romantic poets. Wordsworth the great celebrator of the power of nature seldom directly describes the summer season or indeed any season without some reference to its relationship to the development of man’s soul. His greatest evocations of summer are in fact those which embody in part a sense of loss. In both ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey’, and ‘Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood’, he recalls the joy in nature of childhood, now, in his philosophy, inevitably lost to the adult man, but replaced by something perhaps deeper if more tinged with sorrow. In ‘Tintern Abbey’ (1798), he reflects:

For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still sad music of humanity …

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

Only Wordsworth could move so seamlessly from ocean, air and blue sky to ‘in the mind of man’. As ever with Wordsworth, the prepositions matter. ‘The mind of man’ would be both too general and too prosaic; ‘in the mind of man’ takes us immediately inward and beyond. And this is the poet’s great feat; he does not describe nature so much as attempt to describe the effect that nature has on us – a sense of the sublime. That feeling we may be lucky to have when we experience a true summer’s day with its sense of infinite beauty going beyond the limits of the actual, green leaves unfurling, a blackbird singing or even a nightingale, the arc of a deep blue sky with blossom set against it, and perhaps even a touch of that otherworldliness of the pagan connections of May. Wordsworth is after all a sort of Pantheist – a believer in there being a soul that ‘rolls through all things’.

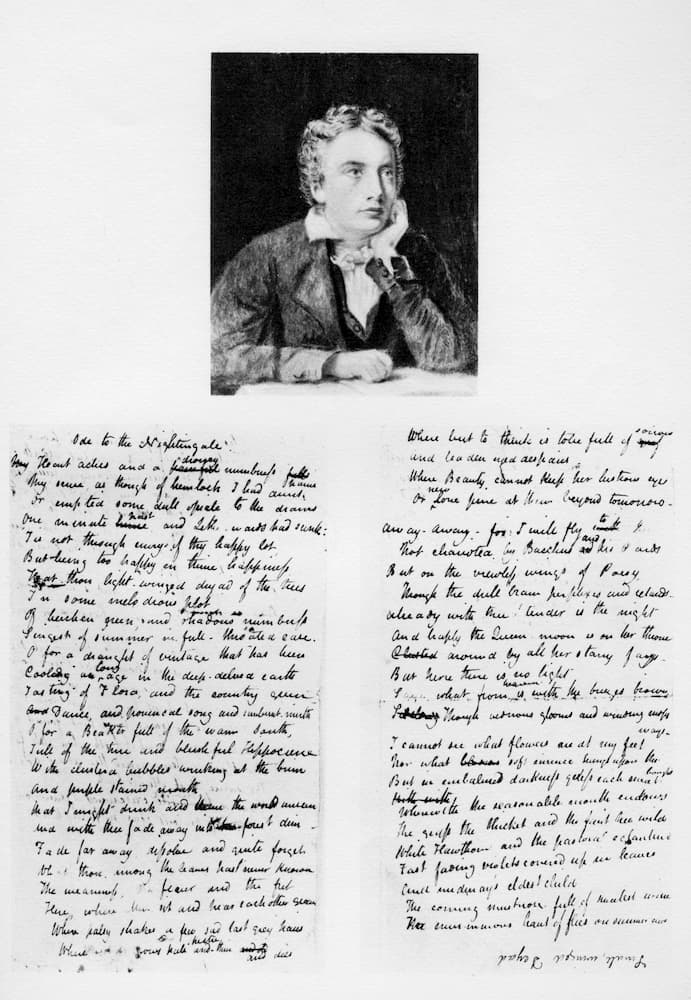

Ode to a Nightingale

But we don’t have to have any form of super-natural belief to feel the pure power of summer. Keats it is for me who best embodies this in poetry, in his ‘Ode to a Nightingale’. Nightingales can be heard right now in Kent as no doubt in many other parts of the country. Keats is said to have heard one in the garden of the house where he was staying in the Spring and Summer of 1819, in the then semi-rural Hampstead, and to have written the first draft of the Ode thus inspired under a plum tree in that garden. Keats’ poem was thus fully located in the actual, but he draws on a long poetic tradition to invoke ideas and feelings about mortality and immortality, the precariousness of beauty, and the power of the imagination. Central to the poem, however, is the sense of summer all around, and the real thrill of the nightingale’s song (heard usually as light fails, hence Keats’ references to darkness):

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast-fading violets cover’d up in leaves;

And mid-May’s eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,

The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

The evocation is the more powerful because it is created through other senses than sight. And it is in the midst of this that the poet feels

… too happy in thy happiness, –

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

Summer is indeed icumen in.

The Collected Poems of both William Wordsworth and John Keats are published by Wordsworth, as are the novels mentioned in this blog.

My text for ‘Sumer is icumen in’ is drawn from Mediaeval English Lyrics, A Critical Anthology, ed. R. T. Davies, Faber and Faber.

Main image: May blossom Credit: Fellsphoto Flora / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Sumer Is Icumen In, c. 1260-1270. Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Tess 1893. Oil on canvas by James M. Nairn. Credit: Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Rows of Stooks of oats. Credit: Fotolincs / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Tintern Abbey. Credit: Billy Stock / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: John Keats and his ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, 1819 Credit: The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

Tess of the D’urbervilles (Collector’s Edition)

Thomas Hardy

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Thomas Hardy

Lady Chatterley’s Lover

D.H. Lawrence

Mary Barton

Elizabeth Gaskell

The Complete Poems of John Keats

John Keats

The Collected Poems of William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth