Elizabeth Gaskell and ‘Lois the Witch’

The name Elizabeth Gaskell probably conjures up associations with her more well known social realist novels such as Mary Barton (1848), North and South (1855) and Cranford (1853). Yet, during much of her writing career she remained fascinated with the supernatural and produced numerous ghost stories. In her biographical work The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) Gaskell relays an anecdote of her telling a ghost story to Charlotte Brontë shortly before bedtime. Brontë apparently ‘shrank from hearing it, and confessed that she was superstitious’. Many of Gaskell’s ghost stories were originally published in the popular journal Household Words, edited by none other than Charles Dickens. Often, her stories would appear in special editions produced for Christmas, because, as we all know, the festive season is the season for ghosts. A comprehensive selection of these tales have been gathered together in Tales of Mystery and the Macabre as part of the Wordsworth Mystery and Supernatural series, featuring an introduction by David Stuart Davies.

I should point out that Gaskell’s gothic stories are not merely chilling ghostly tales lacking in the kind of political and social issues addressed in her novels. If anything, the gothic form gave Gaskell greater freedom to engage with concerns which were dear to her heart, such as social and political injustice particularly as it related to women’s lives. Many of her gothic tales take as their point of inspiration actual or legendary events, two such examples being her short story ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’ and her novella ‘Lois the Witch’. Yet these supposed similarities are a little misleading as when you delve deeper into her gothic tales it becomes apparent her ghost stories employed a variety of narrative styles and subject matter. For example, the inspiration for ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’ originates from a Haworth legend of a woman who was seduced by her brother-in-law and became pregnant. She was locked up by her father and shunned by her sisters and the ghosts of the woman and her daughter were said to have haunted the local area.

Other stories in the collection are similarly varied in nature. For example, ‘Disappearances’ is more of a series of anecdotes rather than a story with a single narrative focus, and as the title suggests, relays accounts of various people who disappeared under mysterious circumstances. In contrast, ‘The Poor Clare’ whilst also fictionalizing local legends and actual events, adopts a stronger supernatural stance, whereas ‘The Squire’s Story’ is much more satirical in style.

‘Lois the Witch’ casts back to New England, America in the 1690s and takes as its inspiration the events of the Salem Witch Trials. The American setting may seem unusual, but Gaskell wrote the story with an American audience in mind. However, it was initially serialized in All the Year Round in October 1859, an appropriate offering for Halloween. The Nineteenth Century British reader would probably have had some familiarity with the Salem Witch Trials, as a number of paintings were produced during the Century detailing various scenes from the trials. Gaskell’s research on the historical context surrounding the Salem Witch Trials was largely based on the work of Unitarian Boston minister Charles Upham’s Lectures on Witchcraft, Comprising a History of the Delusions of Salem, in 1692 published in 1830.

Salem memorial and house

The basic events of the Salem Witch Trials are that in 1692, 19 people were convicted of witchcraft and taken to Gallows Hill, which was a barren slope near Salem Village, where they were hanged. Another man who was over 80 years old was pressed to death under heavy stones for refusing to submit to a trial on witchcraft charges. Hundreds of others faced accusations of witchcraft. Many languished in jail for months on end without trials. Then, almost as soon as it had begun, the hysteria that swept through Puritan Massachusetts ended. There was nothing particularly new or unusual about accusations of witchcraft. What was significant was the rapidity with which the charges spread and the fact that all claims and accusations of witchcraft were believed. More people were executed in the Salem Witch Trials than had previously been executed in the history of New England.

Gaskell’s novella begins in May 1691, nine months before the witch hunting epidemic started in February 1692. Orphaned Lois Barclay has left her home in Warwickshire to live with her Puritan Aunt and Uncle in Salem, Massachusetts. Lois has no living relatives in England, her parents have recently died and her last remaining Uncle was killed in the battle of Edgehill in the English Civil War. Thus, Gaskell starts her tale by blending fact with fiction. Some have theorized Lois was based on the real-life figure of Rebecca Nurse, however, I would dispute this as Nurse was in her 70s in 1692.

Gaskell successfully uses the first chapter to establish the context of fear and hardship experienced by the settlers in Puritan New England. She embeds into her tale some of the reasons which are thought to have combined to contribute to the rising hysteria which led to the spiraling accusations, trials and executions. The ongoing frontier war with American Indians was a constant source of fear and anxiety as well as a drain on resources. Add to this a harsh winter, religious disputes, various personal jealousies, congregational strife and teenage boredom and this becomes the perfect storm which made way for the trials.

Lois becomes aware of some of these issues as soon as she arrives and before undertaking the last part of her journey to Salem. The kindly Captain Holdernesse who accompanies Lois describes the New Englanders as ‘a queer set… They are rare chaps for praying; down on their knees at every turn of their life.’ Her temporary stop over with Widow Smith will prove to be far more welcoming than the home reluctantly offered by her Aunt. The unfamiliar ways of the Puritans immediately make Lois feel lonely and out of place. That Puritan women are required to keep silent is made clear through mention of the unusual status enjoyed by Widow Smith as her benevolence ‘gave her the liberty of speech which was tacitly denied to many.’

In addition to the Puritan ways, the unfamiliarity of the American landscape and the presence of American Indians contribute to the growing sense of trepidation experienced by Lois. Gaskell draws on her reading of Upham’s work as Widow Smith tells her:

‘…folk are ordered to keep four scouts, or companies of minute-men; six persons in each company; to be on the look-out for the wild Indians, who are for ever stirring about in the woods, stealthy brutes as they are! I am sure, I got such a fright the first harvest-time after I came over to New England, I go on dreaming, now near twenty years after Lothrop’s business, of painted Indians with their shaven scalps and their war-streaks, lurking behind the trees, and coming nearer and nearer with their noiseless steps.’

Thus, Widow Smith makes clear the strangeness of the land in which Lois finds herself. This short speech blends reference to actual measures and events along with existing fears and superstitions. The mention of Minute Men refers to military force set up to respond instantly to attacks from American Indians. Similarly, Lothrop’s business refers to a real event in which Thomas Lothrop and his men were ambushed and killed by American Indians. This blending of facts with the opinions and fears of gives a certain weight to Widow Smith’s words. Thus, her description of the strange appearance of the American Indians and their ‘lurking behind the trees,’ moving with ‘noiseless steps’ immediately established them as different, threatening and possessing supernatural powers.

The Seventeenth Century Puritan feared what might be lurking in the unknown wilderness and the Captain’s warning ‘it is not safe to go far into the woods’ connects superstition with actual sources of danger. The settlers were under constant threat of attack from American Indians and from the French Catholics from Canada. Elder Hawkins declares ‘Satan hath many powers’ and their enemies were sent by the devil to distract them from their Christian purpose. This corrupting force extended by trying to recruit witches into their number, and through talk of witchcraft Lois unfortunately makes an enemy of Elder Hawkins. Lois refers to witchcraft scares in England, but speaks in sympathetic terms saying they ‘are fearful creatures, the witches! and yet I am sorry for the poor old women, whilst I dread them.’ Elder Hawkins will remember such dangerous talk when he later encounters Lois in Salem.

Salem house

Lois does not receive a warm welcome when she arrives at what is to be her new home in Salem. She has the unfortunate combination of being very pretty and free thinking. Her ability to stand up for herself immediately gets her off on the wrong foot with her Aunt Grace Hickson, and her beauty attracts the unwanted attentions of her cousin Manasseh. Her looks and warm temperament also stir up jealousy in her cousin Faith as Lois also catches the eye of Pastor Nolan, who Faith is in love with. In Lois, Gaskell has created a character who was ahead of her time, not just in Seventeenth Century Puritan New England, but arguably in Nineteenth Century England as well. Not only does Lois express her opinions, she is sympathetic to falsely accused witches, and intends to control her own destiny when it comes to matters of marriage.

Most of the characters in Gaskell’s tale are fictional although there have been suggestions some are based on real people. Lois is told of religious conflict between Mr Tappau and Mr Nolan and this is probably based on what happened between the real-life residents Reverend Samuel Parris and Reverend George Burrows, the latter being found guilty of witchcraft. Cotton Mather is referred to by Grace Hickson and indeed makes an appearance when the accusations of witchcraft gather momentum. Mather actually existed although did not take part in the real trials. Instead, he was asked to write a record of the proceedings by the three judges. This became The Wonders of the Invisible World and was published in 1693. To add to the interest of Gaskell bringing him in as a character is the fact that she used the name Cotton Mather Mills as a pseudonym for some of her early short stories published in Howitt’s Journal.

The Hicksons have an elderly American Indian servant by the name of Nattee. She tells the girls frightening stories by the fire during the long winter evenings and enjoys the sense of power this gives her. Gaskell uses this moment to insert some social commentary stating the girls were ‘of the oppressing race, which had brought her down into a state little differing from slavery, and reduced her people to outcasts on the hunting-grounds which had belonged to her fathers.’ Figures such as Nattee existed and indeed she is reminiscent of the real-life Tituba, an American Indian servant in the household of Samuel Parris, who used to entertain his girls with supernatural tales, and was indeed the first to be executed for being a witch.

The harsh winter mentioned in the tale contributed to the ongoing difficulties of life in Salem. Gaskell draws on Upham’s records and evokes the supernatural atmosphere through description of:

‘… the absolute stillness of the night – season – the white mist, coming nearer and nearer to the windows every evening in strange shapes, like phantoms… the hungry yells of the wild beasts approaching the cattle-pens, – these were the things which made that winter life in Salem, in the memorable time of 1691-2, seem strange and haunted…’

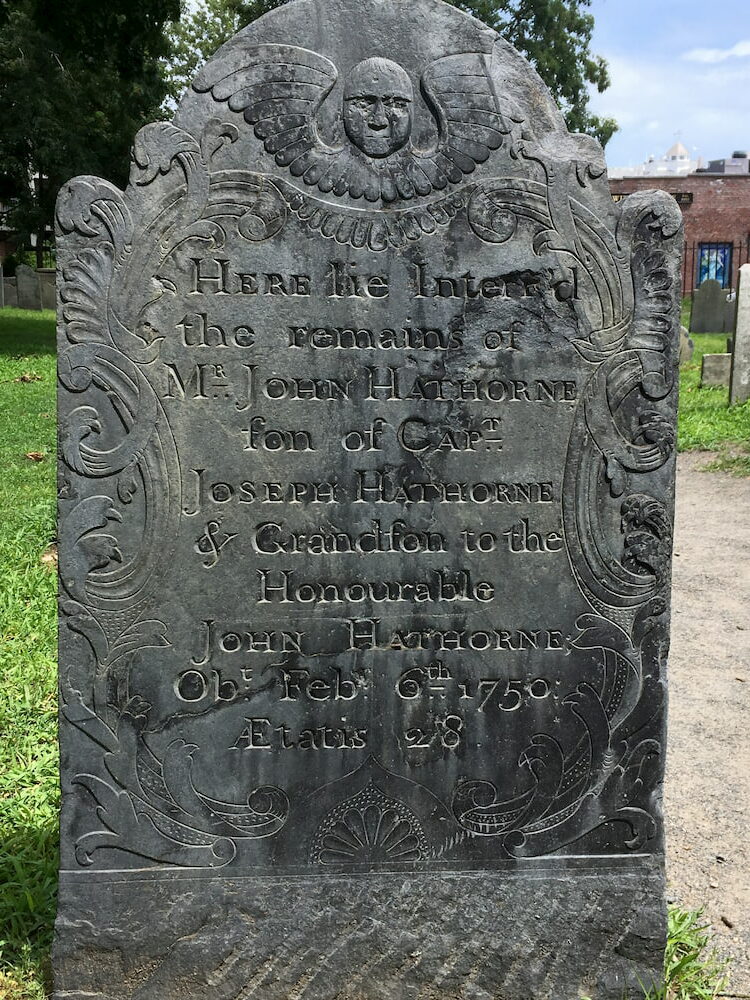

Grave of John Hathorne

Lois’s personal troubles increase alongside the difficult living conditions, where the threat of Satan is taken as a reality. Reports surface of the strange behaviour of Mr Tappau’s daughters who begin to cry out as if they were being pinched by invisible fingers. Gaskell seems to take her inspiration from the unexplained illness which befell the daughter and niece of Samuel Parris, Mr Tappau’s real life counterpart. The two girls complained of fever, became contorted with pain and alternately babbled nonsense or fell silent. Unable to find a suitable explanation, the local doctor began to suspect witchcraft as the cause and other girls fell ill with unexplained symptoms.

The sense of fear and panic of witchcraft spreads throughout the village and the narrator explains how:

‘Some in dread of death confessed from cowardice to the imaginary crimes of which they were accused, and of which they were promised a pardon on confession. Some, weak and terrified, came honestly to believe in their own guilt…’

Lois admits ‘I grow frightened of everyone’ as well she might, as her tenuous status as an outsider makes her ripe for blaming as the source of all the problems. Her own Aunt clutches at the idea Lois has bewitched her children as a means of explaining her son’s deteriorating mental condition and Lois is ‘led before Mr Hathorne.’ Again, Gaskell brings in a real figure. John Hathorne was one of the judges at the trials and was also the Great-Great-Grandfather of Nathanial Hawthorne, and it is thought the Hawthorn family adjusted their name in order to distance themselves from the trials.

Gaskell concludes her tale by explaining how later that year Salem ‘awakened from their frightful delusion’ and she reproduces the declaration of regret issued by the jurors and published in Upham’s work. She uses the narrative voice to ask the reader to ‘remember that Grace, along with most people of her time, believed most firmly in the reality of the crime of witchcraft.’ This emphasizes that although accusations of witchcraft may have been a convenient way of disposing of enemies, the inhabitants of New England had a genuine belief in the presence of Satan and his witches in their land.

Main image: Witch statue in Salem, Massachusetts. Credit: Heidi Besen / Alamy Stock Photo

Images of Salem above courtesy Denise Hanrahan Wells

Books associated with this article