Book of the Week: Tess of the d’Urbervilles

On the day of Thomas Hardy’s birth, David Stuart Davies looks at Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the book that some consider being his finest work.

Although Tess of the d’Urbervilles is set firmly in the Victorian age, the narrative has a very modern edge to it in that many of its controversial elements are relevant today. The novel follows the fortunes of a pretty country girl, Tess, the plot revolving around rape, illegitimate birth and adultery against a background of rural spoliation. This sprawling novel is imbued with Hardy’s philosophy concerning the futile actions of man. Hardy was a great believer in Fate as the ruler of our destiny. He was of the opinion that no matter what actions we take in life, we cannot change the preordained path set out for us. Fate, combined with dark unfortunate coincidences, blighted the lives of his leading characters in most of his novels, none more so than Tess.

Unfairness dominates the lives of Tess and her family. She is unjustly punished for her rape by Alec and is shunned by society. Happiness is constantly snatched from her grasp by a series of unfortunate incidents, none of which she is responsible for. Tess’s death at Stonehenge at the end of the novel reminds us of a world where the gods are not just and fair, but whimsical and uncaring. When the author concludes the novel with the statement that ‘‘Justice’ was done, and the President of the Immortals (in the Aeschylean phrase) had ended his sport with Tess’, Hardy is making makes the point that Justice must be put in ironic quotation marks since it is a false concept. What passes for ‘Justice’ is in fact one of the pagan gods enjoying a bit of ‘sport,’ or a frivolous game. Symbolically Tess dies on the altar used for sacrifices to the sun. In essence, as the sun rises, she is sacrificed to the so-called guardians of social and moral laws.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles presents complex pictures of both the importance of social class in nineteenth-century England and the difficulty of defining class in any simple way. Certainly, the Durbeyfields are a powerful emblem of the way in which class was no longer evaluated in Victorian times as it would have been in the Middle Age – that is, by bloodstock alone, with no attention paid to fortune or worldly success. Indubitably the Durbeyfields have purity of blood yet, for society at the time, this fact amounts to nothing more than a piece of genealogical trivia. In the Victorian context, and one might argue that the same applies today, cash matters more than lineage. In this society the nouveau riche d’Urbervilles pass for what the Durbeyfields truly are – authentic nobility – simply because definitions of the class have changed. Money and power rather than purity and nobility are the important attributes now.

Tess of the d’Urbervilles presents complex pictures of both the importance of social class in nineteenth-century England and the difficulty of defining class in any simple way. Certainly, the Durbeyfields are a powerful emblem of the way in which class was no longer evaluated in Victorian times as it would have been in the Middle Age – that is, by bloodstock alone, with no attention paid to fortune or worldly success. Indubitably the Durbeyfields have purity of blood yet, for society at the time, this fact amounts to nothing more than a piece of genealogical trivia. In the Victorian context, and one might argue that the same applies today, cash matters more than lineage. In this society the nouveau riche d’Urbervilles pass for what the Durbeyfields truly are – authentic nobility – simply because definitions of the class have changed. Money and power rather than purity and nobility are the important attributes now.

The issue of class confusion even affects the Clare clan, whose most promising son, Angel, is intent on becoming a farmer and marrying a milkmaid, thus bypassing the traditional privileges of a Cambridge education and life at a parsonage. His willingness to work side by side with the farm labourers helps endear him to Tess, and their acquaintance would not have been possible if he were a more traditional and elitist aristocrat. Thus, the three main characters in the Angel-Tess-Alec d’Urberville triangle are all strongly marked by confusion regarding their respective social classes, an issue that is one of the main concerns of the book.

The changing nature of rural life is also examined during the course of the novel. Hardy saw that modern methods and industrialisation were destroying the idyllic country’s way of life that he idolised. Hardy’s writing often explores what he called the ‘ache of modernism’, and this theme is notable in Tess, which, as critic Dale Kramer noted portrays ‘the energy of traditional ways and the strength of the forces that are destroying them’. In depicting this theme Hardy uses imagery associated with hell when describing modern farm machinery, as well as suggesting the effete nature of city life as when the milk sent there must be watered down because townspeople cannot stomach the natural unadulterated version. Angel’s middle-class fastidiousness makes him reject the simple and pure heart Tess, a woman whom Hardy presents as being in complete harmony with the natural world. When he parts from her and goes to Brazil, he becomes so ill that he is reduced to a ‘mere yellow skeleton’. All these instances can be interpreted as indications of the negative consequences of man’s separation from nature, both in the creation of destructive machinery and in the inability to rejoice in pure and unsullied nature.

Though now considered a major nineteenth-century English novel and possibly Hardy’s fictional masterpiece, Tess of the d’Urbervilles received mixed reviews when it first appeared, in part because of the dramatic implications regarding the sexual morals of late Victorian England. It initially appeared in a censored and serialised version, published by the British illustrated newspaper ‘The Graphic’ in 1891 and in unexpurgated book form in 1892.

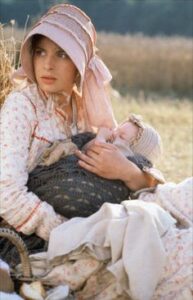

The story has fascinated readers ever since and there have been many dramatic versions of the tale on stage, screen, television and radio. The novel was adapted for the stage for the first time in 1897 and this adaptation was subsequently made into a motion picture by Adolph Zukor in 1913. In 1906 an Italian operatic version was performed in Naples, but the run was cut short by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius. When the opera came to London three years later, Hardy, then 69, attended the premiere. In recent years there have been several musical versions of Tess including a rock opera which premiered in 2007. A four-hour BBC adaptation in 2008 had a starry cast which included Gemma Arterton (Tess), Eddie Redmayne (Angel), Ruth Jones (Joan), Anna Massey (Mrs d’Urberville), and Kenneth Cranham (Reverend James Clare).

The story has fascinated readers ever since and there have been many dramatic versions of the tale on stage, screen, television and radio. The novel was adapted for the stage for the first time in 1897 and this adaptation was subsequently made into a motion picture by Adolph Zukor in 1913. In 1906 an Italian operatic version was performed in Naples, but the run was cut short by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius. When the opera came to London three years later, Hardy, then 69, attended the premiere. In recent years there have been several musical versions of Tess including a rock opera which premiered in 2007. A four-hour BBC adaptation in 2008 had a starry cast which included Gemma Arterton (Tess), Eddie Redmayne (Angel), Ruth Jones (Joan), Anna Massey (Mrs d’Urberville), and Kenneth Cranham (Reverend James Clare).

Notable film versions include Roman Polanski’s elegiac interpretation of the tale with Nastassja Kinski as Tess in 1996 and Trishna, a modern retelling of the story set in India. This movie follows the book’s arc, taking Trishna, a ‘pure woman’, on a journey of hope and disappointment. It effectively underlines the timelessness and universality of Hardy’s drama and the continuing relevance of the plot.

Books associated with this article

Tess of the D’urbervilles (Collector’s Edition)

Thomas Hardy