‘Eveline’s Visitant’

‘Strange reports had gone forth about me; and there were those who whispered that I had given my soul to the Evil One…’

‘Mary Elizabeth Braddon was a contemporary of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins, and yet is nowhere nearly as well known. If her name does spark any recognition, it is usually in connection with her novel Lady Audley’s Secret, published by Wordsworth Classics with an Introduction by Esther Saxey. Yet Braddon’s output during her life was prolific, often producing two novels a year, most of which were serialized in the popular magazines of the time. She also wrote plays, poetry and short stories. Curiously though, it is Lady Audley’s Secret and Aurora Floyd, both published in 1862, which have received most of the academic attention over the years, despite the fact that her publishing career began in 1860 with Three Times Dead and ended with Mary, published posthumously in 1916.

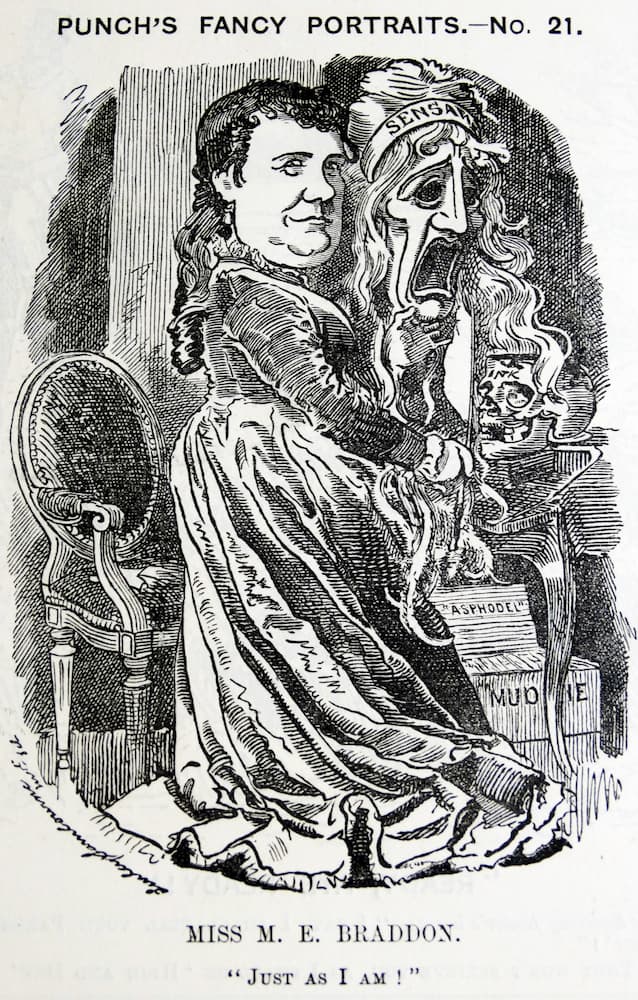

Portrait of the author by By Edward Linley Sambourne 1881

Her biography reads a little like a plot from one of her own sensational novels and Stephen Carver’s article on Lady Audley’s Secret provides comprehensive details. However, to summarise, her parents’ marriage was not a happy one and eventually they became estranged. In 1852, at the age of seventeen, Mary became an actress in order to support herself and her mother, using the stage name Mary Seyton. This was not a respectable way for women to earn money and thus began her rather dubious reputation. She gave up acting to pursue her writing career fulltime after meeting publisher John Maxwell in 1859. Their relationship soon combined the professional with the personal and she moved into his home as his wife. The only problem was, Maxwell was still married to Mary Anne, who was either living with her family or was constrained within an asylum in Ireland, depending on which version of the story you believe. Nevertheless, Braddon and Maxwell pretended to be married and had children together. Eventually the truth behind their façade came out which caused a fair amount of scandal, although they were eventually legally married following the death of Maxwell’s wife in 1874.

In addition to Braddon’s novels, she wrote a number of short stories, many with a supernatural feel. These were published in the popular journals of the time, although were not anthologized during her lifetime. One of these stories, ‘Eveline’s Visitant’ can be found in Classic Victorian and Edwardian Ghost Stories edited by Rex Collins, in Wordsworth’s Tales of Mystery and the Supernatural.

‘Eveline’s Visitant’ was originally published in Belgravia magazine in 1867, some six years after Lady Audley’s Secret. Belgravia was Braddon’s own magazine, which she started in 1866 and edited for ten years. This story differs in some ways from the sensation novel genre which made Braddon famous. These frequently take typical upper class or middle class settings such as the country house as their premise. Instead, Braddon creates a sense of distance as the opening line tells the reader ‘It was at the masked ball at the Palais Royal that my fatal quarrel with my first cousin André de Brissac began.’

The first-person male narration immediately draws the reader in as we realise he is about to tell us an important story:

‘I can feel the chill breath of that August morning blowing in my face, as I sit in my dismal chamber at my chateau of Puy Verdun tonight, alone in the stillness, writing the strange story of my life. I can see the white mist rising from the river, the grim outline of the Chatelet, and the square towers of Notre Dame black against the pale-grey sky.’

Memorial in St Mary Magdalene church, Richmond-upon-Thames

Braddon successfully creates a strong sense of place, alerting the reader to the narrator’s location in Paris through mention of his view of ‘Notre Dame’ with such specific details creating a feeling of authenticity about the tale. That his view may be partially obscured by ‘the white mist rising from the river’ as he sits in his ‘dismal chamber’ suggests this will not be a happy tale. The ominous feeling is strengthened through further evocation of the senses as he feels a ‘chill breath’ of an ‘August morning’, all of which compounds the increasingly gothic tone. Braddon achieves all of this by the third paragraph of the story.

Our narrator draws upon his memories to reveal he was ‘a rough soldier’ who quarreled with his cousin, André de Brissac, a man of superior status. It is only at this point our narrator is given a name, Hector, and we learn the dispute was over a woman and took place at a masked ball. It is intimated a duel followed as he strikes his cousin on the face, they fight, and the cousin is ‘mortally wounded’.

Hector immediately regretted his actions and begged forgiveness. However, such forgiveness was not forthcoming and André responded with the chilling words: ‘I will be with you when you least look to see me’. André’s anger at his approaching death was clear as he issued forth a curse:

‘I will come to you when your life seems brightest. I will come between you and all that you hold fairest and dearest. My ghostly hand shall drop a poison in your cup of joy… It is my will to haunt you when I am dead.’

Braddon’s use of short, sharp sentences, evoke the feeling of André’s failing breath as he delivers this dire warning to his cousin. Thus, Braddon has nicely set up the scenario for a ghostly tale. The language used, has a feeling of an earlier time period, as does the cause of death by duel, and these aspects, added to the European castle like setting evokes an earlier style of gothic writing. The second word of the title is worth considering too. The term ‘visitant’ is an archaic term to refer to a visitor, but it can also suggest the visitor may be some kind of supernatural being. The threat to the narrator’s future happiness is clear, despite the fact he has inherited his cousin’s chateau, land and wealth. As might be expected, Hector reveals he was initially consumed by guilt and as he was shunned by villagers due to his deed, and for three years led a reclusive life.

Eventually Hector tires of his solitude, and travels to Paris where he meets the beautiful and angelic Eveline. They marry and return home where he joyfully informs the reader of the change in his emotional fortunes to match his material gains:

‘Ah, how sweet a change there was in my life and in my home! The village children no longer shrank appalled as the dark horseman rode by, the village crones no longer crossed themselves…’

Annesley today

This is all thanks to the presence of Eveline who wins over the hearts of the villagers. Their married life is happy and Hector has all but forgotten his guilt. Now, the seasoned reader of ghost stories will realise by now that such ‘halcyon hours’ are destined to be short lived. It is not for me to reveal the finer details, other than to say this is an intriguing tale which at times is quite psychological in nature and somewhat reminiscent of that master of gothic Edgar Allan Poe. The suspense and tight control maintained by the narrator is comparable to ‘Ligeia’ which can be found in Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

It would appear Braddon is drawing on her imagination in creating the French setting in this story, as there is little evidence to suggest she travelled abroad. In a letter to Edward Bulwer-Lytton, her literary mentor, she bemoans the amount of time she devotes to her writing, saying ‘I am not able to stir from London, or would spend my money in travelling; but am altogether bound hand and foot by hard work.’[i] Later though, she was able to spend time away from their home in Richmond as her continuing success allowed her to have a country residence built in the hamlet of Bank, near Lyndhurst in the New Forest. This large house, by the name of Annersley, was completed in 1884, by which time she was a respectable married woman. Braddon became something of a celebrity in the area, and their summer visits were often announced in the local newspaper.

This all seems far away though, from the estate of Puy Verdun described in this story which ‘lay in the heart of a desolate region’. That ‘Eveline’s Visitant’ is one of Braddon’s most frequently anthologized stories indicates something of the quality and marks it out as worth investigating, along with the other offerings in Classic Victorian and Edwardian Ghost Stories.

Denise Hanrahan-Wells

[i] Quoted in Wolff, R.L., Sensational Victorian: The Life of Mary Elizabeth Braddon, New York: Garland, 1979, p.134.

Main image: Bank at Lyndhurst. New Forest. 1910 Credit: Pictures Now / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: ‘Punch’ portrait by Edward Linley Sambourne, 1881. Credit: Photo 12 / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Bronze relief by J E Hyett in St Mary Magdalene church, Richmond-upon-Thames Credit: Mick Sinclair / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Annesley today, courtesy of Denise Hanrahan-Wells