The Moonstone: The first modern detective story

It is not widely known nowadays that T.S. Eliot had a passion for detective stories. He held Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie in particularly high regard, and kept up with the evolving contemporary genre, frequently reviewing new tales of mystery and detection in The Criterion, the literary magazine he both created and edited. He even reviewed a couple of ‘True Crime’ books. Mystery and detective novels had grown out of Victorian sensation fiction and were still a relatively new form in the heyday of The Criterion in the interwar years, and Eliot’s endorsement certainly helped authors and publishers, adding literary gravitas to what was essentially still a guilty pleasure. Eliot did, however, draw the line at what were becoming known as ‘thrillers’, for example the Bulldog Drummond stories of ‘Sapper’ (H. C. McNeile), Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu series, and The Mind of Mr. J. G. Reeder by Edgar Wallace. Once described by George Orwell as ‘for pure snootiness it beats anything I have ever seen,’ The Criterion was never going to get behind popular fiction. Eliot viewed these pulp novels as contrived and inelegant, relying on shocks and plot twists over the more sober reasoning and character development of the masters of the form like the ‘Queen of Crime’, Agatha Christie. But for Eliot, the pinnacle of English detective fiction, the text against which all others must be weighed, measured, and counted, was not by Christie, or Dorothy L. Sayers, or even Conan Doyle. Instead, it was a novel that by the early 20th century had largely been forgotten – The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins.

Though a popular novelist in the 1860s, Collins had gone off the boil after The Moonstone, his later novels more political and polemical. As Algernon Swinburne quipped:

What brought good Wilkie’s genius nigh perdition?

Some demon whispered—‘Wilkie! have a mission.’

Collins had always brought social issues into his novels by stealth, but now the theme was the story, with sensation replaced by social commentary. This was nowhere near as much fun to read as The Woman in White or The Moonstone. He had also lost his best friend and mentor Charles Dickens, who had died ‘exhausted by fame’ in 1870; he was plagued by rheumatoid arthritis and gout, his eyesight was failing, and he was hopelessly addicted to laudanum. By the Modernist era, therefore, his novels had not stood the test of time, and were consigned to the same dustbin of literary history that contained the works of W.H. Ainsworth and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Ellen (‘Mrs. Henry’) Wood, ‘Ouida’ (Maria Louise Ramé), and R.D. Blackmore – all bestselling Victorian novelists whose work was now ignored by the academy as melodramatic rubbish and overlooked by a reading public that had been raised on an entirely new generation of popular writers. Collins was, for example, included in Professor Malcolm Elwin’s 1934 study of ‘forgotten’ 19th century authors, aptly named Victorian Wallflowers. But a rehabilitation was in the offing, noted by Elwin, who quoted Eliot’s comment that ‘The Moonstone is the first and greatest of English detective novels.’

Eliot had given readers and publishers a ‘hook’, a tagline that put Collins’ last significant novel – written in 1868 – in a wider context, bringing it up to date within a popular and still relatively new genre. You will see this line quoted everywhere, in every introduction to a new edition of The Moonstone, in reviews of TV adaptations, and academic essays. Rarely, if ever, is Eliot quoted further on the subject. He did, however, have a lot more to say about Wilkie Collins and detective fiction in general which remains relevant today in any serious exploration of the novelist and the genre he helped to invent, before being superseded by Sherlock Holmes and forgotten for 50-odd years. To any contemporary Victorianist, the exclusion of Wilkie Collins from the literary canon would be unthinkable. For this, we have T.S. Eliot and his love of detective stories to thank.

Group photograph including Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins

Eliot’s famous line on The Moonstone is taken from his 1927 essay ‘Wilkie Collins and Dickens’, which formed the introduction to the 1928 Oxford World’s Classics edition of the novel. In this piece, he argued that ‘the work of the two men ought to be studied side by side’ as ‘their relationship and their influence upon one another is an important subject of study.’ Eliot’s thesis is that Dickens excelled in character while Collins was ‘a master of plot and situation,’ and that both learnt from each other in their greatest works. Eliot sees Collins’ influence on narrative structure and event in Bleak House, Little Dorrit and ‘parts of Martin Chuzzlewit’, and Dickens’ genius for the ‘kind of reality which is almost supernatural’ in character creation rubbing off on Count Fosco and Marian Halcombe in The Woman in White. That said, it is these characters only, suggests Eliot, that make The Woman in White ‘great’. They are dramatic in a sea of melodrama, whereas ‘The one of Collins’s books which is the most perfect piece of construction, and the best balanced between plot and character, is The Moonstone.’

Eliot goes as far as comparing The Moonstone to Bleak House as ‘The theft of a diamond has some of the same blighting effect on the lives about it as the suit in Chancery.’ Most importantly, it is the ‘first and greatest of English detective novels.’ In specifying ‘English’, Eliot is removing Collins from ‘the detective story, as created by Poe.’ Poe’s detective stories – ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’, ‘The Mystery of Marie Rogêt’, and ‘The Purloined Letter’ – are, writes Eliot, ‘as specialized and as intellectual as a chess problem,’ whereas:

[T]he best English detective fiction has relied less on the beauty of the mathematical problem and much more on the intangible human element. In detective fiction England probably excels other countries; but in a genre invented by Collins and not by Poe. In The Moonstone the mystery is finally solved, not altogether by human ingenuity, but largely by accident. Since Collins, the best heroes of English detective fiction have been, like Sergeant Cuff, fallible; they play their part, but never the sole part, in the unravelling. Sherlock Holmes, not altogether a typical English sleuth, is a partial exception; but even Holmes exists, not solely because of his prowess, but largely because he is, in the Jonsonian sense, a humorous character, with his needle, his boxing, and his violin. But Sergeant Cuff, far more than Holmes, is the ancestor of the healthy generation of amiable, efficient, professional but fallible inspectors of fiction among whom we live today.

Eliot’s advice to modern writers is that ‘there is no contemporary novelist who could not learn something from Collins in the art of interesting and exciting the reader.’ This is because:

The contemporary ‘thriller’ is in danger of becoming stereotyped; the conventional murder is discovered in the first chapter by the conventional butler, and the murderer is discovered in the last chapter by the conventional inspector — after having been already discovered by the reader.

The Cluedo model, he seems to be saying, is already established to the point of cliché. However, he concludes, ‘The resources of Wilkie Collins are, in comparison, inexhaustible.’

In the same year – 1927, also, coincidently the year of the last Sherlock Holmes story, ‘The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place’ – Eliot developed this advice in The Criterion in ‘Homage to Wilkie Collins: An omnibus review of nine mystery novels’, in which the nine authors reviewed are schooled by The Moonstone. Eliot, in fact, lays down ‘some general rules of detective technique’ for authors, all of which he derives not from Conan Doyle but Collins, because:

[A]s detective fiction observes the rules of the game, so it tends to return and approximate to the practice of Wilkie Collins. For the great book which contains the whole of English detective fiction in embryo is The Moonstone; every detective story, so far as it is a good detective story, observes the detective laws to be drawn from this book.

Of the nine novels under review, all of them, says Eliot, violate at least one of these rules, though Collins never did. Eliot’s ‘rules’ (slightly shortened here) are as follows:

(1) The story must not rely upon elaborate and incredible disguises … Disguises must be only occasional and incidental: here Wilkie Collins is impeccable. Elaborate double lives, in disguise, are an exaggeration of this vice.

(2) The character and motives of the criminal should be normal. In the ideal detective story we should feel that we have a sporting chance to solve the mystery ourselves; if the criminal is highly abnormal an irrational element is introduced which offends us. If the crime is not to have a natural motive, or is without motive altogether, we feel again that we have been tricked.

(3) The story must not rely either upon occult phenomena, or, what comes to the same thing, upon mysterious and preposterous discoveries made by lonely scientists. This, again, is the introduction of an irrational element.

(4) Elaborate and bizarre machinery is an irrelevance. Detective writers of austere and classical tendencies will abhor it. Some of the Sherlock Holmes stories make far too much of stage properties. Writers who delight in treasures hid in strange places, cyphers and codes, runes and rituals, should not be encouraged … But in The Moonstone, the Indian business is perfectly within the bounds of reason. Collins’s Indians are intelligent and resourceful human beings with perfectly legitimate and comprehensible motives.

(5) The detective should be highly intelligent but not superhuman. We should be able to follow his inferences and almost, but not quite, make them with him. It is perhaps in the Detective that the contemporary story has made the greatest progress – progress, that is to say, back to Sergeant Cuff. I am impressed by the number of competent, but not infallible professionals in recent fiction: Scotland Yard, or as it is now called, the C.I.D., has been rehabilitated. The amateur detective no longer has everything his own way. Besides the C.I.D. Inspector, another type is successful: the medical scientist whose particular work brings him into touch with crime … One of the most brilliant touches in the whole of detective fiction is the way in which Sergeant Cuff, in The Moonstone, is introduced to the reader. He is unimpressive, and dreary … [But] It is not that Cuff has superhuman powers; he has a trained mind and trained senses.

Any genre savvy reader will have by now recognised many of the tropes, good and bad, in the vast output of detective fiction, film, and television that continues to enthral us. Were it not so popular, after all, there would be no profit in producing these stories. And, as Eliot argues, they all go back to ‘the celebrated Cuff’, Collins’ understated but brilliant detective with a penchant for roses.

*

Like The Woman in White, The Moonstone is narrated by several different point of view characters: Gabriel Betteredge (House-Steward – head servant – of Julia, Lady Verinder); the evangelical Drusilla Clack (the poor niece of Lady Verinder); Matthew Bruff (the Verinder family solicitor); Franklin Blake (cousin and suitor of Rachel Verinder, Julia’s daughter and owner of the ‘Moonstone’ diamond); Ezra Jennings (the terminally ill and opium addicted assistant of Dr Candy, the family doctor); Dr Candy; Sergeant Cuff; and Rosanna Spearman (housemaid; posthumously, by letter). There is also a prologue and epilogue, and a preface by the author. Franklin Blake, the notional hero – another ‘Walter Hartright’ figure – acts as editor, having asked the contributors to put their experiences on the record ‘in the interests of truth.’ The device is a legal one, that of witness testimony, though intended to obscure rather than reveal. This is a novel of secrets; its complex structure and unreliable narrators immerse the reader in a murky world of contradictory information, evidence that is difficult to interpret, and sketchy clues.

The prologue ‘Extracted from a family paper’ tells the story of the storming of Seringapatam on May 4, 1799, by British East India Company forces, a decisive military action in the conquest of South India. It is written in the form of a long letter by a cousin and brother officer of Colonel John Herncastle, Lady Verinder’s brother. He is writing to explain why he has disowned Herncastle, who has looted a huge yellow diamond – the ‘Moonstone – from the statue of an Indian deity, Chandra, Hindu god of the Moon, killing the three holy men guarding it, the last of whom dies uttering the curse: ‘The Moonstone will have its vengeance yet on you and yours!’ The disgraced Herncastle has been estranged from his family ever since, and when he dies, he leaves the diamond to his niece, Rachael Verinder, to be given to her on her eighteenth birthday in 1848. Whether this is a redemptive act or one of spite is not clear, although in gifting the diamond he passes on the relentless pursuit of the Brahmin pilgrims committed to the recovery of the sacred diamond.

The adventurer Franklin Blake is charged with bringing the diamond safely from London to the Verinder country house in Yorkshire. He, of course, quickly falls in love with Rachael, though he has a rival in the philanthropist and lay preacher Godfrey Ablewhite. Several guests are in attendance for Rachael’s birthday party at the house, and on the same night the Moonstone is apparently stolen from her room. Lady Verinder reluctantly calls in the local police, led by the ineffectual Superintendent Seegrave, who is ill-equipped in both intellect and experience to solve the mystery, which is looking increasingly like an inside job. He is soon replaced by the sharp but melancholy London detective Sergeant Cuff. Suspicion initially falls on three travelling Indian street performers who have been seen in the area, the housemaid Rosanna Spearman (a disabled Reformatory girl with a criminal past who is acting strangely), and Rachael herself, whose behaviour has inexplicably changed and who refuses to cooperate with the police investigation. Alongside Cuff, Franklin also acts as an investigator, both men aided by Betteredge, who has become caught up in ‘detective-fever’. If you are not already familiar with the story, I guarantee you will not see the resolution coming.

You will note here the (now) familiar devices of the English detective story:

- A crime in a country house

- An inside job

- Multiple suspects and misdirection

- Police procedure

- Incompetent local constabulary

- A celebrated if eccentric detective

- Clues, coded messages, and concealed evidence…

Though not apparent from my summary, there is also a reconstruction of the crime, a medical examiner and early psychological profiler (Ezra Jennings), the detective summing up the case, and a startling final twist. After several characters are apparently incriminated, the perpetrator is also the least likely suspect. As Eliot notes, Collins has given us the complete template for the modern detective story in The Moonstone. Like the ‘hero’s Journey’, it can be seen everywhere in mystery and crime narratives, from the Sherlock Holmes stories to Jonathan Creek and Scooby-Doo.

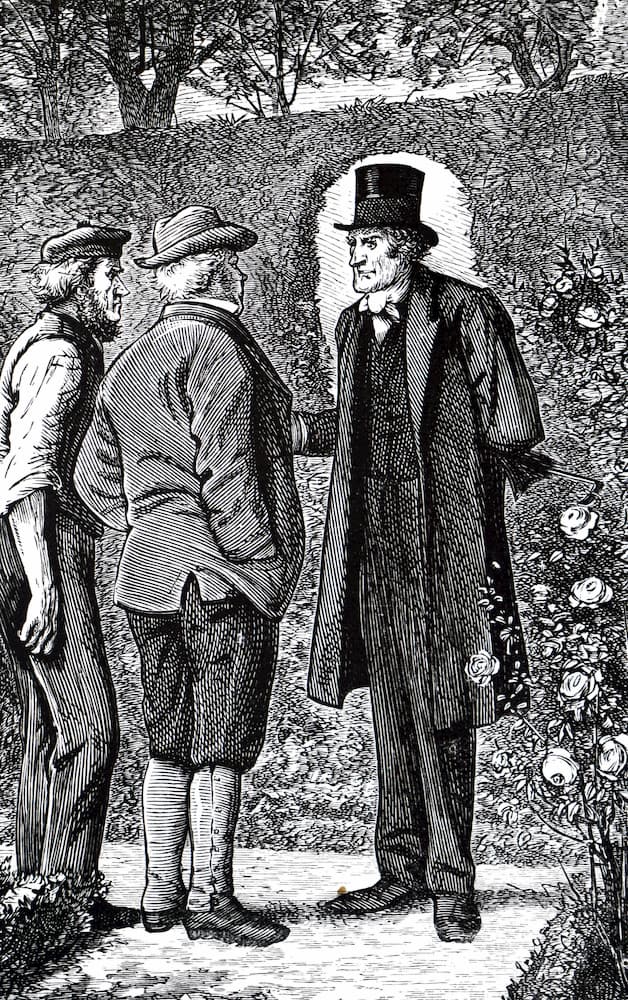

Like Peter Falk’s Lieutenant Columbo, Sergeant Cuff is not what people expect:

[O]ut got a grizzled, elderly man, so miserably lean that he looked as if he had not got an ounce of flesh on his bones in any part of him. He was dressed all in decent black, with a white cravat round his neck. His face was as sharp as a hatchet, and the skin of it was as yellow and dry and withered as an autumn leaf. His eyes, of a steely light grey, had a very disconcerting trick, when they encountered your eyes, of looking as if they expected something more from you than you were aware of yourself. His walk was soft; his voice was melancholy; his long lanky fingers were hooked like claws. He might have been a parson, or an undertaker—or anything else you like, except what he really was.

The only thing that truly seems to animate him is the subject of growing roses, about which he argues joyously with the Verinder family gardener every chance he gets. (This is one of the novel’s running gags, alongside Miss Clack’s propensity for distributing religious tracts.) And just like Columbo, this modest man, easy to underestimate, misses nothing and is relentless in his inquiries. He has ‘roundabout’ and ‘underground’ ways of investigating, luring suspects into giving away more than they should. But, as Eliot wrote, he is also human and fallible. Cuff is not Sherlock Holmes or Batman. He observes, he deduces, he makes plays; sometimes he’s right, and sometimes he isn’t, and if he cannot solve a case, he will accept no payment.

Sergeant Cuff discusses roses with Gabriel Betteridge.

Cuff was based on the real Victorian policeman Detective Inspector Jack Whicher (1814 – 1881), one of the original eight members of London’s newly formed Detective Branch, established at Scotland Yard in 1842. Whicher was well known in the popular press (Dickens wrote about him twice in Household Words), having solved several notorious crimes in Britain and Europe. Detached and methodical, Whicher had a reputation for cracking complex cases, but it was the one that defeated him that bears the most similarity to the plot of The Moonstone.

On the night of June 29,1860, in the small village of Road (then in Wiltshire; it’s now ‘Rode’ in Somerset), the 3-year-old Francis Savile Kent disappeared from the bedroom of his nursemaid, one Elizabeth Gough. His mutilated body was found the next morning, stuffed into an outhouse used by servants in the garden of his family home, Road Hill House. The Kents were a prosperous middle-class family. Savile’s father, Samuel Kent, was the Home Office Inspector of Factories for Southwest England. His mother was the second Mrs. Kent and had been the governess of Savile’s small army of older half-siblings before the first Mrs. Kent had gone mad and subsequently died. The horrific crime attracted national press attention because of the social status of the family, stoked when preliminary police investigations found no sign of a forced entry, suggesting that the murderer was a member of the household. The fact that Kent had married one of his own servants, with whom he was almost certainly having an affair before his first wife died, added further grist to the mill. A theory grew that Gough had been in bed with a lover when the boy had woken up and was killed to keep the secret. This would have at least protected the reputation of the family, transferring blame to an outside agent and a servant, but it didn’t hold water, even though Gough was arrested twice. Gough knew no one in the village. Further speculations followed, including this one from Dickens, who wrote to Collins at the time:

Mr Kent intriguing with the nursemaid, poor little child awakes in crib and sits up contemplating blissful proceedings. Nursemaid strangles him then and there. Mr Kent gashes body to mystify discoverers and disposes of same.

Dickens was not alone in this conjecture, and Kent’s private life was picked apart by gossipmongers because of his penchant for sleeping with his servants. A modern correlative to the ‘Road Hill House Murder’ would be the disappearance of Madeleine McCann. Everyone was following the story; everyone had a theory.

It was clear from the start that the local police were hopelessly out of their depth, and after two weeks Inspector Whicher arrived from Scotland Yard to take charge of the investigation. By this time, the crime scene had been trampled by local coppers, journalists, and sightseers, and any useful clues had been destroyed. The killer had also had ample time to cover their tracks, and the family was refusing to cooperate with the investigation. Whicher seized on the only piece of evidence he did have, a missing nightgown belonging to Savile’s 16-year-old half-sister Constance that was logged in the washing book but never received by the washerwoman. Constance was a troubled teenager, who had possibly inherited her mother’s mental health problems; she blamed her stepmother for her mother’s death and had once run away from home with her older brother, William. Whicher promptly arrested her on suspicion of murder. Because of the class difference between accused and accuser, the Road community and much of the national press took Constance’s side and she was soon released by the local magistrate on the grounds of insufficient evidence. The case collapsed.

Publicly humiliated and still convinced of Constance’s guilt, Whicher returned to London, his reputation in tatters. The Kent family moved to Wrexham and sent Constance to a finishing school in France. She confessed to the murder five years later. Her death sentence was commuted to life in prison, and she was released after twenty years. (She changed her name and emigrated to Australia, dying in 1944 aged 100.) It later emerged that Wiltshire police had found a bloodstained nightgown hidden in a boiler. They had lost it in a failed attempt to catch the culprit returning to dispose of it properly and Whicher was never told. The officers charged with watching the boiler had accidently locked themselves in the kitchen.

Though considerably less gory than the true story, Collins took much from the Hill House murder, understanding that it was all about family secrets. Like the original case, the crime appears to originate in the household once an attempt to pin it on outsiders (the Indians) fails. The police then immediately move on to suspecting the servants. The middle-class family at the heart of the mystery close ranks and refuse to cooperate with the investigation. The local police are useless, and when the suspicions of the London detective, Cuff, fall on the daughter, Rachael, he is hampered by her silence and ultimately leaves the investigation, only to return briefly at the end of the story. (Franklin then takes over as an amateur detective, as Walter Hartright did in The Woman in White.) In common with the Hill House case, a missing nightgown becomes a vital piece of evidence. And like the Kents, the silence of the Verinder family seems to suggest that no one is innocent.

In The Moonstone, all the primary characters conceal things, either to protect themselves or somebody else. There are double lives, secret loves, and mysterious motivations, not unlike the sordid truth – adultery, betrayal, madness, and visceral hatred – hidden beneath the respectable veneer of the Kent family, like the ‘Shivering Sand’ of The Moonstone, a complex and gothic space that seems to represent the unconscious, femininity, and all that is hidden:

I looked where she pointed. The tide was on the turn, and the horrid sand began to shiver. The broad brown face of it heaved slowly, and then dimpled and quivered all over. ‘Do you know what it looks like to me?’ says Rosanna, catching me by the shoulder again. ‘It looks as if it had hundreds of suffocating people under it—all struggling to get to the surface, and all sinking lower and lower in the dreadful deeps! Throw a stone in, Mr. Betteredge! Throw a stone in, and let’s see the sand suck it down!’

There are also parallels between daughters Constance Kent and Rachael Verinder and housemaids Elizabeth Gough and Rosanna Spearman. Their collective unwillingness to talk to investigators placed them all under suspicion of one crime when their silence was intended to conceal another, one of illicit passion. It was still believed, for example, that Constance was trying to protect her father’s reputation, as was Elizabeth, by covering up the affair, even if it meant a murderer went unpunished. As Collins wrote in his preface to the novel:

In some of my former novels, the object proposed has been to trace the influence of circumstances upon character. In the present story I have reversed the process. The attempt made, here, is to trace the influence of character on circumstances. The conduct pursued, under a sudden emergency, by a young girl, supplies the foundation on which I have built this book.

Only the murder and the theft can be openly acknowledged; there are other things going on in these families that are not to be spoken of, especially by women, whether working- or middle-class. Neither crime represents an invasion of the family home from an outside force that can ultimately be repelled; they are endemic to the structure of the Victorian family. Again, this is a theme that remains present in much contemporary detective fiction and drama. As the detective digs, more and more that is kept hidden is revealed, often secrets and lies not connected to the original crime.

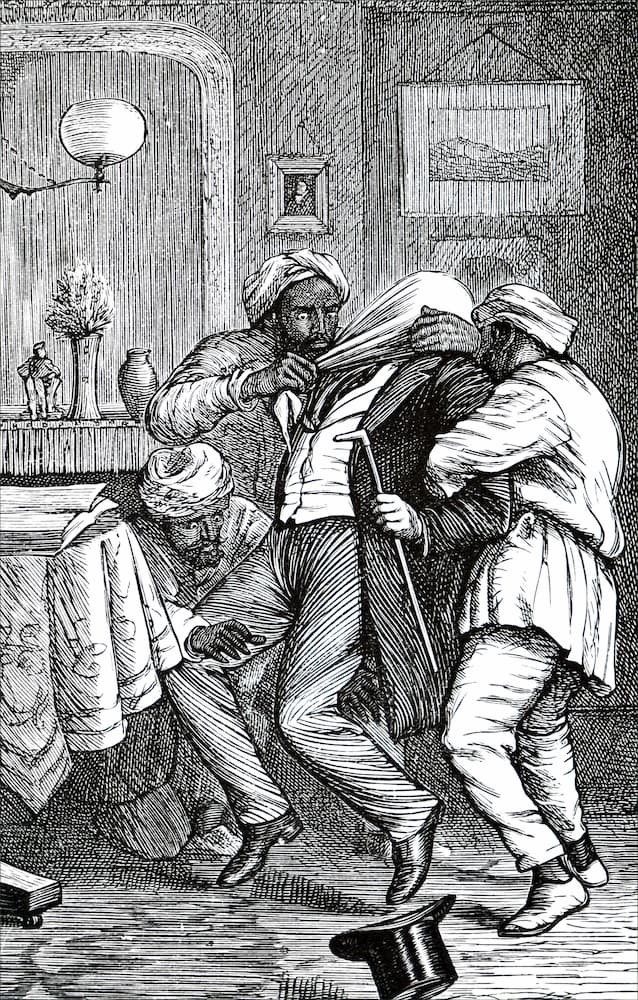

Godfrey Abelwhite is ambushed and searched for The Moonstone by the three Brahmins.

There is, of course, another crime that the Verinders fail to acknowledge, and that is the original theft of the Moonstone by Lady Julia’s brother. The jewel no more belonged to Rachael than it did Colonel Herncastle. It was never his to bequeath. It was a sacred object looted from India, just as the country had been stolen by the British East India Company. The Brahmins in Collins novel are not a sinister and corrupting force from the east, a common racial stereotype in colonial gothic writing that persisted until the end of the century and can frequently be seen in the stories of Kipling and Conan Doyle. Instead, they are honourable, noble men, who have sacrificed everything in their decades-long quest to reclaim the sacred relic. Written just over ten years after the 1857 Indian Mutiny, this is a remarkably progressive line to take. In 1858, Dickens had written in Household Words, for example:

I wish I were Commander in Chief in India. The first thing I would do to strike that Oriental race with amazement should be to proclaim to them in their language, that I considered my holding that appointment by the leave of God, to mean that I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested; and that I was there for that purpose and no other, and was now proceeding, with all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the earth.

Such were the shockwaves across the Empire, that the Indian Mutiny continued to preoccupy the and prejudice the British for the rest of the century, an institutionalised racism that general dismissed Indian culture as ‘savage’ and ‘heathen’. It might be argued that the events of The Moonstone represent the intrusion of imperialism on everyday English life, but this is not the threat of eastern otherness represented in the Imperial Gothic of Conan Doyle’s ‘The Speckled Band’ or Kipling’s ‘Mark of the Beast’. In The Moonstone, the only thing that can lift the curse is to return the diamond to its rightful owners, the Brahmins.

Collins is similarly rebellious when it comes to the outcasts of society, with prime roles going to a deformed servant girl whose done hard time for theft, Rosanna, her best friend ‘Limping’ Lucy Yolland, a disabled fisherman’s daughter, and Ezra Jennings, Dr Candy’s mysterious assistant. Weird looking and therefore shunned, an unspecified but terminal illness has left Jennings addicted to opium, the latter fact linking him autobiographically to his creator as well as representing a vital plot point. Class as well as gender is a factor, and politically the women are less inclined to remain silent than they are on the subject of the Moonstone. Lucy tells Betteredge, for instance, that ‘the day is not far off when the poor will rise against the rich.’ She has no time for men either, and imagines a life with Rosanna without them:

‘I had saved up a little money. I had settled things with father and mother. I meant to take her away from the mortification she was suffering here. We should have had a little lodging in London, and lived together like sisters. She had a good education, sir, as you know, and she wrote a good hand. She was quick at her needle. I have a good education, and I write a good hand. I am not as quick at my needle as she was—but I could have done. We might have got our living nicely.’

In her introduction to the 1962 Everyman edition of The Moonstone, Dorother L. Sayers argues that Collins was unique among his contemporaries for being ‘genuinely feminist’ in his treatment of women in his fiction. Rosanna, meanwhile, makes the powerful point that the only difference between her and Rachael as women is the trappings of wealth: ‘Suppose you put Miss Rachel into a servant’s dress, and took her ornaments off? … it does stir one up to hear Miss Rachel called pretty, when one knows all the time that it’s her dress does it, and her confidence in herself.’ And while Lucy has only one important part to play in the plot, Collins gives the narrative over to both Ezra and Rosanna, much as Henry Mayhew reproduced interviews verbatim with the subjects of his seminal work of social investigation, London Labour and the London Poor, and Chartist activist and Dickens’ hated rival G.W.M. Reynolds gave working class characters long monologues in his epic penny dreadful series The Mysteries of London. While Collins was bringing intrigue and drama to the middle-class home, he was also depicting the working classes in a way Dickens never would, shunning, as he did, political solutions as demonstrated by his criticism of trade unions in Hard Times. There’s some strong social satire in there as well, with Miss Clack’s evangelical proclivities sent up something rotten. Like the eccentric life of its author, there is something decidedly subversive about The Moonstone that makes us question our conception of the Victorian novel. In short, there is something very modern about it, which returns us to contemporary detective fiction. Knives Out and Glass Onion are not so different in construction, right down to the different and conflicting points of view and, of course, the eccentric detective themselves.

The Moonstone represents the high watermark as far Collins’ work is concerned. He earned £750 for the UK serial rights and as much again in America, the equivalent to about £209,000 today. Few authors aside from Dickens earned anywhere near as much or commanded such a huge readership. In his 1900 memoir Random Recollections of an Old Publisher, William Tinsley, who published The Moonstone in book form, recalled the impact of the original serial:

During the run of ‘The Moonstone’ as a serial there were scenes in Wellington Street that doubtless did the author’s and publisher’s hearts good. And especially when the serial was nearing its ending, on publishing days there would be quite a crowd of anxious readers waiting for the new number, and I know of several bets that were made as to where the moonstone would be found at last. Even the porters and boys were interested in the story, and read the new number in sly corners, and often with their packs on their backs…

Not since The Woman in White has there been such a clamour for the next instalment. But this is the moment when the wave broke and began to roll back. The composition had taken its toll. As Collins wrote in the preface to the novelised edition of 1871: ‘when not more than one third of it was completed, the bitterest affliction of my life and the severest illness from which I had ever suffered, fell on me together.’ His mother was on her deathbed, and he was stricken with ‘rheumatic gout’, an agonising condition. Nonetheless, ‘I held to the story’, he writes, because ‘I had my duty to the public.’ Relying on laudanum and an amanuensis, he took to his bed and dictated the serial, later claiming there were several parts that he had no recollection of composing. This horrible cycle of pain, opium, the side effects of opium – the epic nightmares so memorably described by Thomas De Quincey – and then more pain leaks out in Jennings’ narrative:

June 16th.—Rose late, after a dreadful night; the vengeance of yesterday’s opium, pursuing me through a series of frightful dreams. At one time I was whirling through empty space with the phantoms of the dead, friends and enemies together. At another, the one beloved face which I shall never see again, rose at my bedside, hideously phosphorescent in the black darkness, and glared and grinned at me. A slight return of the old pain, at the usual time in the early morning, was welcome as a change. It dispelled the visions—and it was bearable because it did that.

Collins continued to take opium for the rest of his life, viewing it as an essential medicine, knowing that he couldn’t stop even if he wanted. Ironically, his father had been a friend of Coleridge, whose creative powers were also ruined by the drug.

And so, Collins’ star paled. He kept writing, but never again achieved the creative success of the 1860s, the golden decade that began with The Woman in White and ended with The Moonstone, the two books now most closely associated with his name. Though aside from John Forster he was Dickens’ closest friend, Forster edits him out of his Life of Dickens almost completely, while his colourful private life (he lived with two women, neither of whom he married), meant that proposed memorials at Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s Cathedral after his death in 1889 never happened. This was the Victorian era after all.

Thus, it was left to T.S. Eliot to remind readers how good Collins had been, rather than just another second fiddle to Dickens. And his opinion was soon echoed by Dorothy L. Sayers, who described The Moonstone as ‘probably the very finest detective story ever written,’ and G.K. Chesterton, who called it ‘probably the best detective tale in the world.’ Purest may argue that The Notting Hill Mystery by ‘Charles Felix’ (Charles Warren Adams) got there first in 1863, and that Clara Vaughan by R.D. Blackmore (1864) features a protagonist in search of her father’s killer. Policemen as characters and mystery plots were not new in the Victorian novel, especially during the sensation fiction era, but if there was already a new British genre forming (for we must not forget Poe in the US), then what Collins achieved in The Moonstone was a masterful consolidation of these various ideas and narrative codes into the recognisably modern detective story, transcending what had gone before. This is what Eliot is telling us. We can argue over what or was not the original source of the genre, but what Collins did was define it. This is why there are elements of The Moonstone in Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) and The Sign of Four by Conan Doyle (1890), and why Agatha Christie pinches the punchline in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd in 1926. Every mystery writer owes a debt to The Moonstone, and its influence is just as prevalent today as it was in Eliot’s lifetime. It’s there in the novels of Patricia Cornwell, Richard Montanari, Karin Slaughter, and the rest of that crowd, and in TV shows like Broadchurch, Mindhunter, Happy Valley, Luther… in far too many popular narratives, in fact, to enumerate.

So, whatever your poison, if you’re a fan of detective fiction, or, indeed, a writer of detective fiction, if you’ve not yet read The Moonstone you’re in for a treat. As soon as you start reading, Collins gives you an exotic location and a family schism, the history of the diamond, a ‘heap of the slain’, and John Herncastle with ‘a torch in one hand, and a dagger dripping with blood in the other.’ There is just enough light in this horrible scene to glint off the unnaturally large stone set in the weapon’s hilt ‘like a gleam of fire.’ And this is just the event that triggers the main story. Without looking it up, I challenge you to figure out who done it. Enjoy.

Stephen Carver

Main image: Moonstone pendant on sterling silver chain. Credit: Charline Xia / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: From left to right: Charles Dickens Jr (Charley), Kate Dickens, Charles Dickens, Georgina Hogarth, Mary Dickens, Wilkie Collins Credit: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Engraving depicting a scene from The Moonstone: Sergeant Cuff discusses roses with Gabriel Betteridgeon his way to see Lady Verrinder. Illustrated by Francis Arthur Fraser (1846-1924) an English painter and cartoonist. Credit: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Further engraving by Francis Arthur Fraser. Godfrey Abelwhite is ambushed and searched for The Moonstone by the three Brahmins. Credit: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

For more information on the works of Wilkie Collins, visit: The Wilkie Collins Society

Books associated with this article