A Princess in the Attic

Denise Hanrahan-Wells looks at Frances Hodgson Burnett’s classic Children’s Story

I first came across A Little Princess through the 1973 BBC adaptation and was immediately captivated by it. I am not sure exactly what drew me in but having recently returned to the original novel I realise I was a similar age to the gently heroic Sara Crewe when the narrative begins. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s tale of the experiences of young Sara, born in India and who at the tender age of seven arrives at Miss Minchin’s Select Seminary for Young Ladies in London, has remained in print since its first publication in 1905.

Just to clarify, Sara is not actually a princess, although at the start of the narrative she is extremely privileged, wealthy and much loved by her father Captain Crewe. She arrives at school with an elaborate wardrobe with ‘sable and ermine on her coats, and real Valenciennes lace on her underclothing’ (Chapter 1). Her favourite doll Emily also has an extensive wardrobe and Sara’s status is such that she has her own private sitting-room and a French maid. The very strict Miss Minchin finds her clothing ‘perfectly ridiculous’ for a child of her age, but is more than happy to exploit the benefits of having such a wealthy pupil at her school.

The narrative is a relatively simple one and on the surface this may seem like an ordinary school novel, in that Sara has to overcome her initial homesickness at leaving her beloved father, and cope with a headmistress who does not like her. There are the challenges of making friends as she is unable to win the approval of the clique of popular girls led by the nasty Lavinia. Despite these challenges, Sara settles in and all is well until her eleventh birthday at which point tragedy strikes when Miss Minchin receives news of Captain Crewe’s death. This is where matters take a decided turn for the worst as Captain Crewe has lost his fortune through a disastrous investment in a diamond mine. Sara is left a penniless and homeless orphan at the mercy of Miss Minchin. Rather than turn her out onto the street, Miss Minchin is persuaded to consider her reputation and instead puts Sara to work and banishes her to a cold attic, minus her extensive wardrobe. The rest of the narrative follows Sara’s efforts to survive her harsh living conditions and her attempts to make the best of her situation by relying on her very active imagination. However, if you peel away the top layer of an apparently simple children’s story, it becomes apparent Frances Hodgson Burnett has something to say about child poverty in Edwardian Britain.

The novel went through a number of incarnations, beginning as a serialized short story in 1887, before becoming a successful stage play during the 1890s. In 1905 it was expanded into the novel we now have. Its original title was A Little Princess: Being the Whole Story of Sara Crewe Now Being Told for the First Time. This included an introduction written by Burnett in which she said ‘… between the lines of every story there is another story…’ Burnett’s reasons for expanding and developing the story were, in part, financially motivated. Following her divorce from Swan Burnett and then a second divorce after a disastrous short marriage to Stephen Townsend, a man somewhat her junior, Burnett found herself in need of some additional income. This was solved by transforming the stage version of A Little Princess into a novel.

Frances Hodgson Burnett 1888

This was not Burnett’s first foray into writing. Her early career saw her produce short stories for American magazines. Her first novel, That Lass O’Lowrie’s, set in Lancashire, was published in 1877. Following her marriage to Swan Burnett, she continued to write novels and plays, although her most remembered books are Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886) and The Secret Garden (1911).

In the course of her writing, Burnett may have drawn upon aspects of her own experiences. Her father died in 1852 when she was just three years old. Her father owned an ironmonger and silversmith business in the centre of Manchester. Following his death, her mother tried to keep the business afloat, but not without difficulty. Their finances diminished and the family were forced to move to a smaller home, close to an area of poverty and overcrowded housing. The descriptions of poverty which are present in A Little Princess may have been inspired by some of the images she saw during her childhood, albeit transferred from Manchester to the streets of London. The family finances hit hard times and the decision was made to emigrate to America, and in 1865 they settled in Tennessee.

The novel’s engagement with wealth and poverty has some complexity as there is no simple critique of either. Sara is the richest girl in the school before her father’s loss of fortune, and yet she has the greatest sense of morality of all the characters in the book. Instead of forming friendships with the most popular girls in the school, she befriends a girl by the name of Ermengarde who is somewhat of an outcast because she is ‘a fat child, who did not look as if she were in the least clever’. However, Sara sees beneath this superficial description and notices her ‘good-naturedly pouting mouth’ (Chapter 3). She also forms an attachment to Becky the scullery maid after the exhausted girl accidentally falls asleep in Sara’s sitting-room. When Captain Crewe’s death makes Sara penniless she drops to the same status as Becky the scullery maid. This status is made clear by Miss Minchin when she tells Sara “Becky is the scullery-maid. Scullery-maids are not little girls.” (Chapter 7) This is a very telling comment in the way it dehumanizes her position in the household. An early description of Becky makes clear the impact her life of drudgery has had upon her:

‘She was a forlorn little thing who had just taken the place of scullery-maid – though, as to being scullery-maid, she was everything else besides. She blacked boots and grates, and carried heavy coal-scuttles up and down stairs, and scrubbed floors and cleaned windows, and was ordered about by everybody. She was fourteen years old, but was so stunted in growth that she looked about twelve.’ (Chapter 5)

The scullery maid did indeed hold the lowest rank within the household staff, with the housekeeper, cook, kitchen maid and parlour maid all being her superior. Often scullery maids had the longest working day and were looked down upon by other servants and sometimes were not allowed to eat at the servants’ dining table.

Burnett also presents a kind of hierarchy regarding the subject of child poverty. Although poor Becky is treated appallingly as a scullery maid, she does receive a meagre income. She has a roof over her head, albeit in the cold and comfortless attic, and has a meagre supply of food, provided she is not being punished for something which is not her fault. When Sara loses her place as pupil, she finds herself in the stark and cold attic room next to Becky. However, she receives no income and in many ways her role is less clearly defined but certainly no easier. She too is frequently and unfairly punished by the Cook for some false misdemeanour and often denied dinner. Sara’s way to deal with the daily miseries of her reduced position is to rely on her imagination and she tells Becky: ‘What you have to do with your mind, when your body is miserable, is to make it think of something else.’ (Chapter 13) The something else in Sara’s case is to imagine she is a fairy princess who cannot be hurt or made uncomfortable by anything, and to maintain a sense of dignity regardless of the predicament she finds herself in. She remains determined to behave like a princess on the inside, even when she cannot be one on the outside.

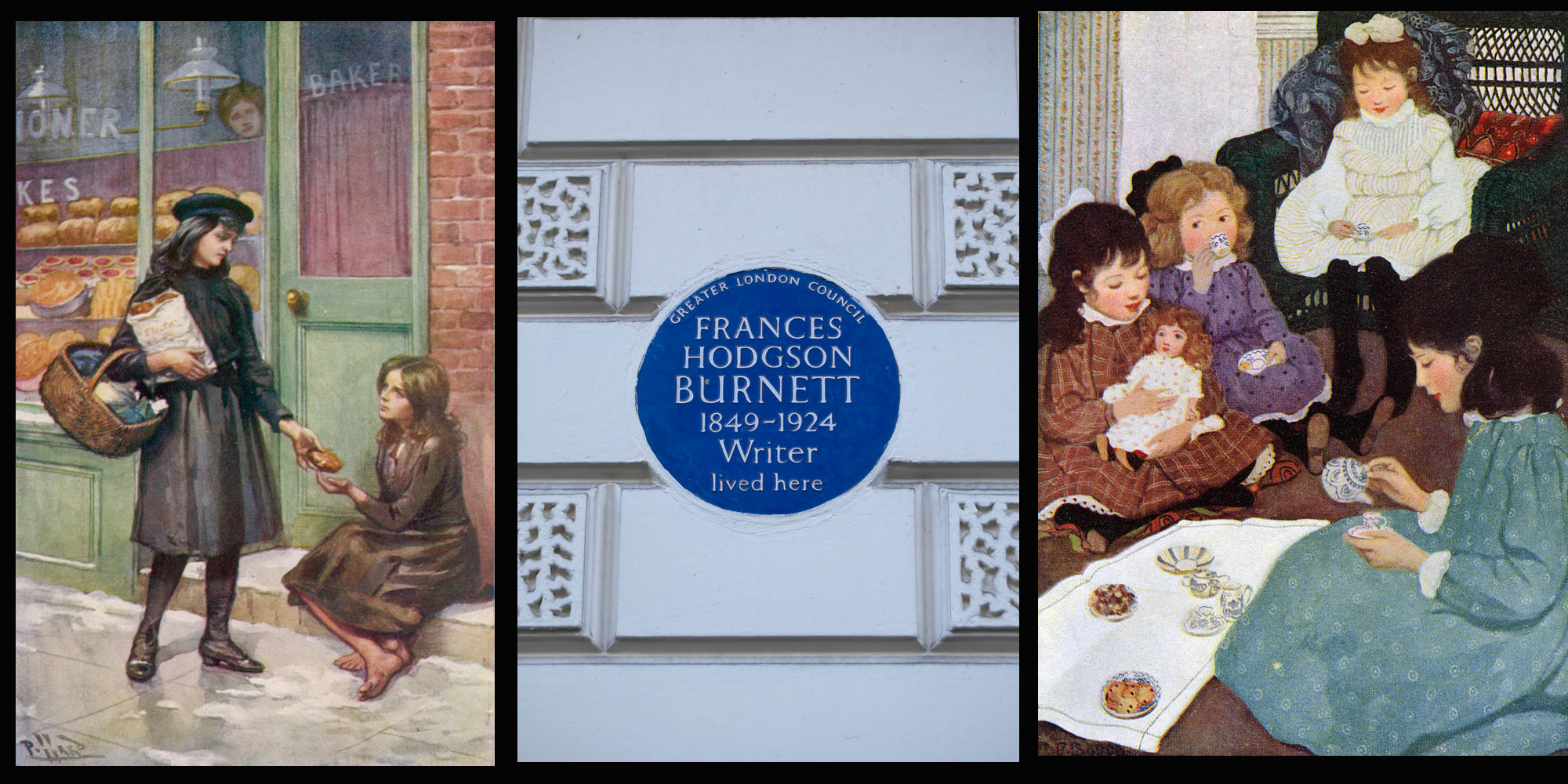

On one of Sara’s most challenging days she encounters a little girl even more forlorn than herself. Although this is children’s fiction, Burnett uses Sara as a kind of observer of her surroundings as the reader learns of her thoughts on the sights and sounds of London during her numerous errands. On this particular day, we learn Sara has been sent out on a number of errands in bad weather in her wet shabby clothes and her ‘down-trodden shoes were so wet that they could not hold any more water. Added to this, she had been deprived of her dinner, because Miss Minchin had chosen to punish her.’ This all occurs in Chapter 13 which bears the socially aware title ‘One of the Populace’. The girl Sara stumbles across is unnamed at this point which is befitting of her status. She is described as:

‘… a little figure which was not much more than a bundle of rags, from which small, bare, red, muddy feet peeped out, only because the rags with which their owner was trying to cover them were not long enough. Above the rags appeared a shock head of tangled hair, and a dirty face with big, hollow, hungry eyes.’

Sara had just found a fourpenny piece in the gutter and was dreaming of buying a bag of freshly baked buns which had tantalizingly appeared in the window of the Bakery. This she does, but gives the bag of buns to the little beggar girl, saving just one for herself.

The language used by Burnett throughout the book is relatively simple to suit the intended reader age, yet this makes some of the harsher images all the more poignant. Despite the novel’s age and the potentially young target audience, Burnett has managed to work in some well-placed social observations. The fact that there have been so many adaptations seems to speak to the timeless nature of the themes of the novel. The first film version appeared in 1917, starring Mary Pickford as Sara. Many of the adaptations differ from the original story, in particular the 1939 version featuring Shirley Temple in the starring role. Numerous other film and TV adaptations take some liberties with the plot, although the 1986 TV series which cast Maureen Lipman as the strict Miss Minchin, remains faithful to the original storyline and even includes some of Burnett’s original dialogue.

Regardless of the success of the various adaptations, it is still worth returning to the original novel. The ways in which the young protagonist navigates her way through life even when she has no control over her change of fortune, and the manner in which she deals with sadness, loneliness and injustice still has as much resonance today as it did in 1905.

Main image: Centre – Blue plaque marking the home of the author, Portland place, London. Credit: Mick Sinclair / Alamy Stock Photo Outer images

Outer images and image of FHB above Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article